A new study from the University of Southern California looks at the gaps between what parents believe and what experts know about students' academic progress since the Covid-19 pandemic.

[W]hen it comes to judging student performance, caretakers relied on grades, other school-reported measures of student progress and their own observations of their children’s work and work ethic, rather than standardized test scores.

Only five of the 40 caretakers who participated in the study mentioned their child’s performance on standardized tests, while all mentioned grades (on assignments, on class tests, on report cards). Standardized test results were not salient considerations regarding children’s well-being. On the other hand, experts’ judgments about the academic impacts of COVID are usually based on changes in standardized test scores. Because parents failed to mention their children's academic standing on standardized tests, the researchers concluded this data source was not as relevant to caretakers.

Parents interviewed for the study knew something was amiss. They gave statements like: “The bar got set so low for completing work and turning things in that the kids kind of got an idea—at least (my child) did, that she didn’t have to do as much.” And: “The curriculum overall has been really kind of dropped down to the lowest kind of denominator.”

Why it matters: The systems designed to produce objective measures of student performance, like standardized tests, aren't primarily designed to inform parents. They're designed to inform decision-makers in government. Parents are left to rely on more subjective measures, like grades, that are subject to inflation and bias.

Key Findings

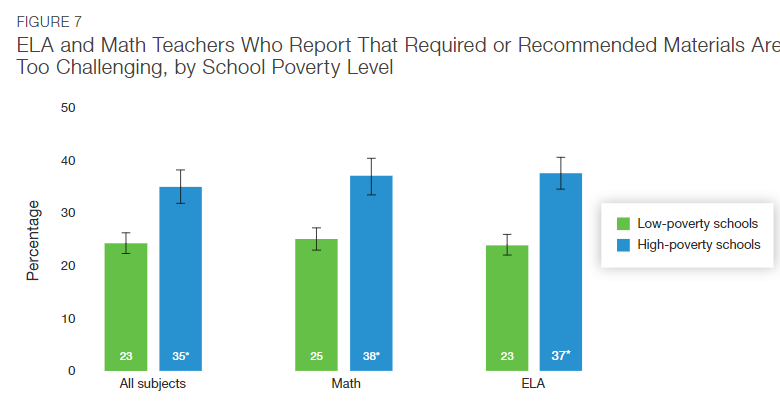

Source: Rand Corporation

Nearly a third of K-12 teachers consider the instructional materials required or recommended for use in their schools to be too challenging for their students.

Students receiving remote instruction during the Covid-19 pandemic reported lower self-efficacy, less school connectedness and higher levels of tobacco use, among other negative effects, compared to students receiving in-person instruction.

Non-cognitive skills like grit may have more to do with students' genetics than their schools' efforts to instill them.

Numbers to Know

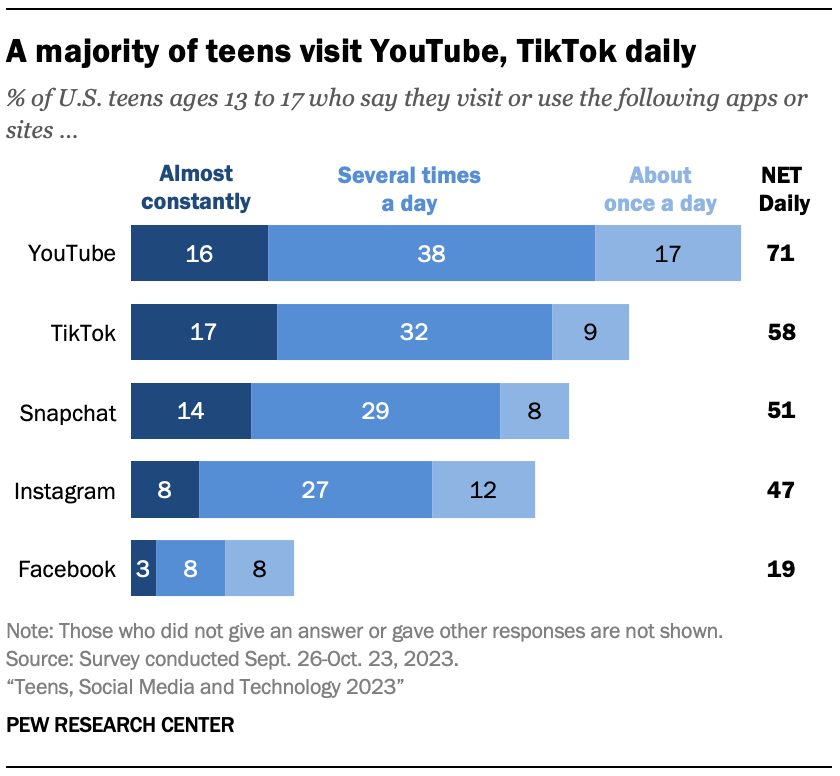

Source: Pew Research Center

22: Percentage of U.S. teenage girls who report using TikTok "almost constantly."

32: Percentage of U.S. Hispanic teens who report the same.

16: Percentage of all U.S. teens who say they use YouTube "almost constantly."