Editor’s note: This post is the second installment of a short series on the origins of K-12 education savings account programs. In the first installment, Dan Lips, a visiting fellow with the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity and the originator of the concept which eventually became the AZESA program, described the turn of the millennium school choice debates that shaped the development of his original ESA proposal. Below, redefinED executive editor Matthew Ladner describes the circumstances that led to the adoption of the first ESA program in Arizona.

Editor’s note: This post is the second installment of a short series on the origins of K-12 education savings account programs. In the first installment, Dan Lips, a visiting fellow with the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity and the originator of the concept which eventually became the AZESA program, described the turn of the millennium school choice debates that shaped the development of his original ESA proposal. Below, redefinED executive editor Matthew Ladner describes the circumstances that led to the adoption of the first ESA program in Arizona.

“Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. One man thinks himself the master of others but remains more of a slave than they are.”- Jean Jacques Rousseau

Arizona and Florida have a long and underappreciated history of exchanging K-12 reforms. Arizona developed the nation’s first scholarship tax credit program; Florida now has the largest scholarship tax credit program. Arizona developed the first education savings program; Florida now has the largest ESA program.

Don’t feel bad because Arizona borrowed school grades, incentive funding and several other policies from Florida. The story of the Arizona ESA program, in fact, begins with Florida’s former Senate President John McKay.

Living in Arizona is like living in the future – your future to be precise. What’s that you say? I don’t know what state you live in? You are right. I don’t know, but it doesn’t matter.

Arizona is both a border state and a retirement destination. Guess what? Day by day, your state is getting a little more like Arizona as your population grows older (10,000 baby boomers per day reaching age 65) and your Hispanic population increases.

Don’t worry too much; your future will be contentious based on Arizona’s last decade, but not so bad. Arizona is the canary in America’s coal mine, but we are still chirping away.

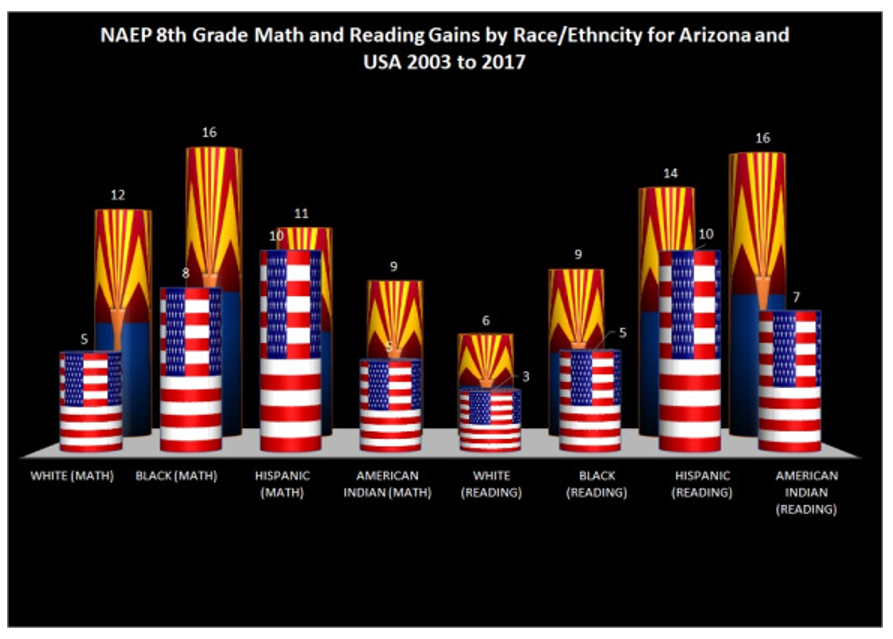

Arizona’s population also doubled since 1990. If you stretch the state level NAEP data back as far as they will go (also 1990) you’ll find that in many comparisons, Arizona tended to rank just ahead of Alabama but behind the other participating states (not all states participated in NAEP until 2003). Arizona is not a high-performing state yet, but we have been heading in the right direction.

Break-neck population growth and low average performance tend to incline the mind toward innovation. The state experienced enormous pressure to build enough school space for the growing student population, but the results were less than “meh” on average. Accordingly, Arizona has the largest state charter sector (around 17 percent of public-school students), an even bigger open enrollment practice and private choice.

Back in the mid-1990s, Arizona lawmakers made three big K-12 decisions: They required districts to have an open enrollment policy and forbade the charging of tuition; they passed a liberal charter school law; and they created the first of what became several private choice programs. These and other reforms seem to be working out well judging by NAEP, with broadly shared improvements in outcomes:

Arizona Gov. Janet Napolitano became the first Democratic governor to sign bills creating new school choice programs into law in a budget deal in 2005. One of these was a voucher program for students with disabilities modeled after Florida’s McKay program. We had been advocating for such a program at the Goldwater Institute for years, as the tax credit program would not be capable of providing private choice options to students with disabilities.

Choice opponents, however, challenged the voucher mechanism in the Arizona courts and ultimately prevailed under a “Blaine Amendment” in the Arizona Constitution – a horrifying result. Given that the state’s tax credit system stood incapable of delivering the level of assistance required to aid special needs students, the Arizona Supreme Court has left matters such that we policymakers could deliver a limited amount of assistance to the general student population, but an entirely inadequate mechanism to aid special needs students. The Arizona justices left a trail of breadcrumbs to follow in their decision, however. More on that below.

Dan Lips had developed a proposal for a multi-use K-12 program four years before the Arizona Supreme Court decision striking down vouchers. Your author’s contribution to this story began in reading the findings of an entirely separate Arizona Supreme Court decision involving CityNorth, an outdoor mall. The Arizona Supreme Court acted in this decision to curtail the use of public subsidies to private companies. The ruling discussed the need for a “public purpose” for subsidies and ruled that the city of Phoenix paying for parking spaces outside a mall didn’t qualify.

Lightbulb!

Educating students is about the clearest public purpose you can get. It occurred to me in reading the CityNorth decision that the Lips account mechanism would clearly fulfill that public purpose. Moreover, it would do so in such a way that no one would ever be required to pay for private school tuition. The state would clearly be providing a subsidy to families under this mechanism, and the families would use the service providers they thought best: certified tutors, therapists, community colleges and universities, online programs, private schools, individual public-school courses, etc.

I bounced this notion off Clint Bolick, the famed Constitutional attorney who at the time oversaw the litigation operation. I had feared I was crazy. I felt great relief when Clint listened to my spiel and assured me I was not crazy. In fact, he was every bit as excited as I was. We scheduled a meeting with Tim Keller, the Institute for Justice attorney who had litigated the Cain vs. Horne case defending school vouchers in Arizona.

We laid out the account concept to him. Tim had an unmistakable look of shock on his face. “You need to watch the oral arguments in the Arizona Supreme Court,” Tim told us repeatedly. He looked like he had seen a ghost. As I watched the Cain vs. Horne oral arguments online 19 times that summer from a cabin in the woods in Prescott, Ariz., I probably had the same look on my face.

Clint and I had sat in the chamber during the Cain vs. Horne hearing at the Arizona Supreme Court, but we had to leave about midway through. Watching a choppy video on sketchy WiFi, I discovered that had we stayed for the entire argument, we would have seen one of the justices quizzing attorneys on both sides regarding whether a theoretical program that provided cash assistance to parents of children with special needs would violate the Arizona Blaine Amendment.

Arizona Supreme Court Justice Andrew D. Hurwitz questioned attorney Donald M. Peters, representing the teachers’ unions and other choice opponents, about what sort of program violates Arizona’s Blaine Amendment, which the Court referred to as the “Aid Clause.” The exchange is revealing:

Justice Hurwitz: Do you agree that the state could pick this population of worthy parents and say to them, ‘Here’s a grant for each of you for $2,500 to be used in pursuit of your children’s education, spend it as you wish?’

Peters (attorney for choice opponents): Yes.

Justice Hurwitz: And if they spend it on a private or parochial school, or on public schools by transferring districts, that would be okay?

Peters: Yes. I think the dividing line is how much the state constrains the choice.

My eyes were as big as saucers. I played the video repeatedly to make sure I wasn’t experiencing an auditory hallucination. I had not: The teacher union’s attorney had made the case in the Arizona Supreme Court that an ESA program would be constitutional.

I read the Cain vs. Horne ruling.

The voucher programs appear to be a well-intentioned effort to assist two distinct student populations with special needs. But we are bound by our constitution. There may well be ways of providing aid to these student populations without violating the constitution. But, absent a constitutional amendment, because the Aid Clause does not permit appropriations of public money to private and sectarian schools, the voucher programs violate Article 9, Section 10 of the Arizona Constitution. (emphasis added).

Dan Lips had been in my ear for years about a multi-use choice model. Neither of us had any idea that years later, Arizona would have the first choice program where opponents attempted to apply relics of 19th century anti-Catholic bigotry against a program for special needs children. ESAs had been a solution in search of a problem, but it found the problem and solved it.

Following a great deal of work by people inside and outside the Arizona legislature, Gov. Jan Brewer signed the first K-12 ESA program into law. The same opponents sued again, but this time it was they who met with defeat in the courts. In a unanimous appellate court ruling that the Arizona Supreme Court chose not to review, the court ruled:

The specified object of the ESA is the beneficiary families, not private or sectarian schools. Parents can use the funds deposited in the empowerment account to customize an education that meets their children’s unique educational needs.

Thus, beneficiaries have discretion as to how to spend the ESA funds without having to spend any of the aid at private or sectarian schools.

Thus, unlike in Cain II, in which every dollar of the voucher programs was earmarked for private schools, none of the ESA funds are preordained for a particular destination. The supreme court has never interpreted the Aid Clause to mean that no public money can be spent at private or religious schools.

This program enhances the ability of parents of disabled children to choose how best to provide for their educations, whether in or out of private schools. No funds in the ESA are earmarked for private schools.

First, the ESA does not require a permanent or irrevocable forfeiture of the right to a free public education.

All the ESA requires is that students not simultaneously enroll in a public school while receiving ESA funds. This same restriction applies to any children who attend private school or are homeschooled.

Second, parents are not coerced in deciding whether or not to participate in the ESA…Parents are free to enroll their children in the public school or to participate in the ESA; the fact that they cannot do both at the same time does not amount to a waiver of their constitutional rights or coercion by the state.

Finally, the ESA does not limit the choices extended to families but expands the options to meet the individual needs of children.

Years later, the small but growing number of ESA programs (Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina and Tennessee have active programs) remain experiments in liberty. The greatest strength of ESAs – the flexibility given to families – creates a complex administrative challenge.

Teams in multiple states, however, have been grinding on this challenge in a learning process. ESA programs, while more administratively challenging, clearly represent a leap forward from the basic voucher model in moving from “school” choice to “educational choice” and creating the opportunity for families to access a wider universe of service providers.

Choice opponents often tend to react to ESAs with some mixture of fear and revulsion, but they need not feel either of these things. State constitutions guarantee funding for public education, and the public almost universally supports those provisions.

This does not, however, mean that we could not or should not build a future in which families exercise greater control over their funding in order to shape an education system that is more pluralistic and effective, customized to individual needs. Education service providers should be transparent to all, but accountable to the families served.

Giving more choice over the schools their children attend represented a crucial first step in empowering families. This struggle is far from finished. Giving families broad discretion within a system of ordered liberty to control their children’s education represents the next step in the empowerment not only of families, but also of educators. Likewise, families have a great deal to gain from a more liberal system of education but educators have even more prospective benefits.

Families and educators have chains to lose, and much, indeed to gain.