The charter school that spurred creation of Academica did not hit the ground running. No, jokes Academica’s founder and president, Fernando Zulueta, in a new redefinED podcast, “We hit the ground falling.”

The charter school that spurred creation of Academica did not hit the ground running. No, jokes Academica’s founder and president, Fernando Zulueta, in a new redefinED podcast, “We hit the ground falling.”

A hurricane, an appendicitis, upset district officials, bad first-year test scores, an accommodating private school – all played a role in Academica’s origin story. Thankfully, it has a happy ending.

The Florida charter sector, now encompassing nearly 700 schools, is celebrating its 25th birthday this year.

Miami-based Academica provides services to 143 of them, and 178 nationwide. Another 1,000 schools in 18 countries participate in its international dual diploma program.

Despite its size – and its success – the organization remains oddly under the radar.

Academica’s core networks are Somerset, Mater, Doral and Pinecrest. According to Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes, whose research on charter school performance is widely respected, all four are making modest to large gains over like students in district schools. The Doral network showed the biggest gains – 142 additional days of learning in math and 57 in reading.

Those results are on par with more celebrated charter organizations like Achievement First, IDEA, BASIS and Great Hearts. So where’s the love?

Zulueta offers his take on that and other issues in the podcast, along with a little history about that first Academica affiliate. Among other insights:

Talent + freedom. “Find the best possible people to run (schools) and give them as much autonomy and control over their environment as possible.”

Let teachers teach. “Anything that wasn’t mission critical to the task of educating students is what Academica sought to do.”

On criticism of for-profits: “There’s this rather demeaning and unfortunate notion among some folks in the public sector that they’re just much smarter than everyone else.”

On why it persists: “Divide and conquer.”

On education savings accounts: “I’m in favor of … anything that empowers parents to access better quality education.”

Natalie Keime, ESOL coordinator and sixth-grade intensive reading teacher at Somerset Oaks Academy in Homestead, delivers a virtual lesson to her students from her home.

Editor’s note: During the holiday season, redefinED is reprising the "best of the best" from our 2020 archives. This post originally published March 26.

About a decade ago, Fernando Zulueta was making a presentation to school district officials in Florida about why his charter school support company, Academica, needed to expand into online learning. For one thing, he told them, charter schools serviced by Academica must better serve students who need flexibility because of their talents (say, an elite gymnast) or their challenges (say, homebound because of illness). For another, he said, you never know when a natural disaster – maybe even a pandemic – might necessitate a transition into virtual instruction.

Fast forward to coronavirus 2020.

Academica, now one of the biggest charter support organizations in America, was among the first education outfits in America to shift online as thousands of brick-and-mortar schools were shuttered. The company began planning for potential closures weeks in advance. And when the closure orders were given in Florida, it trained thousands of teachers, distributed thousands of laptops, and acclimated tens of thousands of students to a new normal – in a matter of days.

“I’m not a doomsday prepper,” Zulueta said. “But when you do the work we do, you have the responsibility to be prepared … and to evaluate risks and contingencies in the future.”

On March 13, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis ordered all public schools in Florida to extend spring break a week so students would not return to school. At the time, the vast majority of Florida districts were about to start their spring break, while a handful of others were ending theirs.

Most of the Academica-supported charter schools in Florida were still a week from break. But by March 16, about 40,000 of their 65,000 students logged into class from home. By week’s end, most of the rest had, too. Within days, Academica’s Florida schools were reporting, based on student logins, nearly normal attendance rates.

“I had a little bit of mixed reaction” when the call came to transition, said Miriam Barrios, a third-grade teacher at Mater Academy of International Studies, an Academica-supported school in Miami. Ninety-nine percent of Mater’s students are students of color; 97 percent are low-income. “A lot of these families don’t have computers. So, it was a little scary.”

“But overall things have gone so well, much better than I expected,” Barrios said.

“It ended up feeling a lot like being in school,” said Claudia Fernandez-Castillo, a parent in Miami whose daughters, ages 11 and 12, attend another Academica-supported school, Pinecrest Cove Academy. “They made the kids feel very comfortable with this massive change in their little lives.”

Academica services 165 charter schools in eight states, including 133 in Florida. Somerset, Mater, Doral and Pinecrest are its main networks. According to the most rigorous and respected research on charter school outcomes, students in all four networks are making modest to large gains over like students in district schools.

It remains to be seen how well schools in any sector respond to what is an unprecedented crisis, and what the impacts will be on academic performance.

School districts are mobilizing quickly. In Florida, most of them still have a few days to prep before the bulk of students return to “school” March 30. To date, there’s been little coverage of how Florida’s 600-plus charter schools are coping (though there’s been a glimpse here and there for charters elsewhere.) Ditto for Florida’s 2,700 private schools. Some are proving nimble and capable. But given the big resource disparities, it’s an open question whether others with large numbers of low-income students have the technology and support they need to turn on a dime.

For Academica, online learning is familiar territory. The organization supports three virtual charters in Florida. It offers online courses for students in its other Florida schools. For a decade, it’s also had an international arm, Academica Virtual Education, that serves thousands of students in Europe who need dual enrollment classes to earn specialized diplomas.

Given the events in China, Zulueta said his team began considering, in January, the possibility of school closures in America. The urgency ramped up in February, when the spread of coronavirus in Italy began affecting Academica students in that country.

In mid-February, Academica-serviced schools in the U.S. sent questionnaires to parents, asking if they needed devices and/or connections for distance learning. They ordered what they needed to fill the gaps. When Gov. DeSantis made what was effectively a closure announcement March 13, Zulueta said, “we were already ready to rock and roll.”

The day after the announcement, Academica used online sessions to do basic training in online instruction for 150 administrators. Over that weekend, it trained 3,000 teachers. Meanwhile, schools distributed several thousand laptops to families, in some cases through drive-through pick-ups. Zulueta said the need ranged from 4 percent at some Academica client schools to 20 percent at others.

Schools also immediately let parents know what was coming Monday.

Zulueta, who has three daughters in Academica-serviced schools, witnessed the new normal at his kitchen table.

“They got up. They logged in. And they went right to class,” he said. His daughters and their classmates wore their usual uniforms. The schools did their best to stick to established bell schedules. “We wanted to keep it as close to what they did at school as possible.”

Like students at Academica-serviced schools throughout Florida, television production students at Doral Academy Preparatory High School have quickly adapted to a virtual learning environment.

Academica uses an online learning platform it created itself. It’s integrated with a number of other tools, including Zoom, the video conferencing software with the “Hollywood Squares” look.

Fernandez-Castillo, the mom at Pinecrest Cove Academy, said she watched over the weekend as friends who are Academica teachers practiced the new online platform with each other. Barrios, the Mater teacher, said she contacted her students’ parents after her training on Friday to tell them she would be testing the platform at 8 that night if they and their children wanted to join. Eight to 10 families did. But she still had some anxiety about Monday morning.

“I thought it was going to be a freak show,” Barrios said. “The computers are going to crash, the kids are not going to log in … “

That’s not what happened. Monday morning was “a little jagged,” she said, because some students experienced technical difficulties and couldn’t log in right on schedule at 8:30. But by 8:50, 90 percent of her students were in. “It was amazing,” she said.

Barrios and other teachers used Monday to get their students familiar with the new set up. Any glitches, like problems with Internet access, were minor, she said. Over the next few days, she and her students quickly cleared little hurdles, like students learning to keep their mics on mute until it was their time to speak, and how to use chat functions to indicate they had a question.

Barrios doesn’t think there’s a long-term substitute for the dynamics of an in-person classroom, where students, in her view, can more easily “bounce ideas off one another.” But as a next best thing, she said what her school is doing is far better than nothing, and not bad at all.

Fernandez-Castillo agreed, and pointed to other upsides. “Everybody’s thrilled with the way this has been done,” she said, referring to other parents. “I think it glued the (school) community together even more.”

Natalie Keime, ESOL coordinator and sixth-grade intensive reading teacher at Somerset Oaks Academy in Homestead, delivers a virtual lesson to her students from her home.

About a decade ago, Fernando Zulueta was making a presentation to school district officials in Florida about why his charter school support company, Academica, needed to expand into online learning. For one thing, he told them, charter schools serviced by Academica must better serve students who need flexibility because of their talents (say, an elite gymnast) or their challenges (say, homebound because of illness). For another, he said, you never know when a natural disaster – maybe even a pandemic – might necessitate a transition into virtual instruction.

Fast forward to coronavirus 2020.

Academica, now one of the biggest charter support organizations in America, was among the first education outfits in America to shift online as thousands of brick-and-mortar schools were shuttered. The company began planning for potential closures weeks in advance. And when the closure orders were given in Florida, it trained thousands of teachers, distributed thousands of laptops, and acclimated tens of thousands of students to a new normal – in a matter of days.

“I’m not a doomsday prepper,” Zulueta said. “But when you do the work we do, you have the responsibility to be prepared … and to evaluate risks and contingencies in the future.”

On March 13, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis ordered all public schools in Florida to extend spring break a week so students would not return to school. At the time, the vast majority of Florida districts were about to start their spring break, while a handful of others were ending theirs.

Most of the Academica-supported charter schools in Florida were still a week from break. But by March 16, about 40,000 of their 65,000 students logged into class from home. By week’s end, most of the rest had, too. Within days, Academica’s Florida schools were reporting, based on student logins, nearly normal attendance rates.

“I had a little bit of mixed reaction” when the call came to transition, said Miriam Barrios, a third-grade teacher at Mater Academy of International Studies, an Academica-supported school in Miami. Ninety-nine percent of Mater’s students are students of color; 97 percent are low-income. “A lot of these families don’t have computers. So, it was a little scary.”

“But overall things have gone so well, much better than I expected,” Barrios said.

“It ended up feeling a lot like being in school,” said Claudia Fernandez-Castillo, a parent in Miami whose daughters, ages 11 and 12, attend another Academica-supported school, Pinecrest Cove Academy. “They made the kids feel very comfortable with this massive change in their little lives.”

Academica services 165 charter schools in eight states, including 133 in Florida. Somerset, Mater, Doral and Pinecrest are its main networks. According to the most rigorous and respected research on charter school outcomes, students in all four networks are making modest to large gains over like students in district schools.

It remains to be seen how well schools in any sector respond to what is an unprecedented crisis, and what the impacts will be on academic performance.

School districts are mobilizing quickly. In Florida, most of them still have a few days to prep before the bulk of students return to “school” March 30. To date, there’s been little coverage of how Florida’s 600-plus charter schools are coping (though there’s been a glimpse here and there for charters elsewhere.) Ditto for Florida’s 2,700 private schools. Some are proving nimble and capable. But given the big resource disparities, it’s an open question whether others with large numbers of low-income students have the technology and support they need to turn on a dime.

For Academica, online learning is familiar territory. The organization supports three virtual charters in Florida. It offers online courses for students in its other Florida schools. For a decade, it’s also had an international arm, Academica Virtual Education, that serves thousands of students in Europe who need dual enrollment classes to earn specialized diplomas.

Given the events in China, Zulueta said his team began considering, in January, the possibility of school closures in America. The urgency ramped up in February, when the spread of coronavirus in Italy began affecting Academica students in that country.

In mid-February, Academica-serviced schools in the U.S. sent questionnaires to parents, asking if they needed devices and/or connections for distance learning. They ordered what they needed to fill the gaps. When Gov. DeSantis made what was effectively a closure announcement March 13, Zulueta said, “we were already ready to rock and roll.”

The day after the announcement, Academica used online sessions to do basic training in online instruction for 150 administrators. Over that weekend, it trained 3,000 teachers. Meanwhile, schools distributed several thousand laptops to families, in some cases through drive-through pick-ups. Zulueta said the need ranged from 4 percent at some Academica client schools to 20 percent at others.

Schools also immediately let parents know what was coming Monday.

Zulueta, who has three daughters in Academica-serviced schools, witnessed the new normal at his kitchen table.

“They got up. They logged in. And they went right to class,” he said. His daughters and their classmates wore their usual uniforms. The schools did their best to stick to established bell schedules. “We wanted to keep it as close to what they did at school as possible.”

Like students at Academica-serviced schools throughout Florida, television production students at Doral Academy Preparatory High School have quickly adapted to a virtual learning environment.

Academica uses an online learning platform it created itself. It’s integrated with a number of other tools, including Zoom, the video conferencing software with the “Hollywood Squares” look.

Fernandez-Castillo, the mom at Pinecrest Cove Academy, said she watched over the weekend as friends who are Academica teachers practiced the new online platform with each other. Barrios, the Mater teacher, said she contacted her students’ parents after her training on Friday to tell them she would be testing the platform at 8 that night if they and their children wanted to join. Eight to 10 families did. But she still had some anxiety about Monday morning.

“I thought it was going to be a freak show,” Barrios said. “The computers are going to crash, the kids are not going to log in … “

That’s not what happened. Monday morning was “a little jagged,” she said, because some students experienced technical difficulties and couldn’t log in right on schedule at 8:30. But by 8:50, 90 percent of her students were in. “It was amazing,” she said.

Barrios and other teachers used Monday to get their students familiar with the new set up. Any glitches, like problems with Internet access, were minor, she said. Over the next few days, she and her students quickly cleared little hurdles, like students learning to keep their mics on mute until it was their time to speak, and how to use chat functions to indicate they had a question.

Barrios doesn’t think there’s a long-term substitute for the dynamics of an in-person classroom, where students, in her view, can more easily “bounce ideas off one another.” But as a next best thing, she said what her school is doing is far better than nothing, and not bad at all.

Fernandez-Castillo agreed, and pointed to other upsides. “Everybody’s thrilled with the way this has been done,” she said, referring to other parents. “I think it glued the (school) community together even more.”

Schools plan to reopen: Schools in the Florida Panhandle are announcing plans to reopen for students. Eight of the nine districts that have been closed since Hurricane Michael landed at Mexico Beach on Oct. 10 now have scheduled return dates. Gulf County employees are back in schools today, with students to follow Tuesday. Holmes and Gadsden students return Monday. Franklin employees are back in schools Monday, and students Tuesday. Teachers are back in Washington County schools Tuesday, and students return Wednesday. Liberty has plans to welcome staff back Wednesday, and students on Monday, Oct. 29. Calhoun sets an Oct. 29 date for staff to return to work, with students coming back Thursday, Nov. 1. Bay County, hit the hardest, is planning to open no later than Nov. 12 by using 200 or more portable classrooms. Only Jackson County has not announced a schedule to resume classes. Panama City News Herald. Florida Department of Education. Associated Press. Bay County School District officials are asking for donations from the public to help rebuild the district. The campaign is asking for school supplies, clothing and jackets for students, and supplies and gift cards for teachers. Panama City News Herald. Private schools in the Panhandle also took a hit from Hurricane Michael. redefinED. Student victims of the storm are looking for structure and routine. Pensacola News Journal.

Schools plan to reopen: Schools in the Florida Panhandle are announcing plans to reopen for students. Eight of the nine districts that have been closed since Hurricane Michael landed at Mexico Beach on Oct. 10 now have scheduled return dates. Gulf County employees are back in schools today, with students to follow Tuesday. Holmes and Gadsden students return Monday. Franklin employees are back in schools Monday, and students Tuesday. Teachers are back in Washington County schools Tuesday, and students return Wednesday. Liberty has plans to welcome staff back Wednesday, and students on Monday, Oct. 29. Calhoun sets an Oct. 29 date for staff to return to work, with students coming back Thursday, Nov. 1. Bay County, hit the hardest, is planning to open no later than Nov. 12 by using 200 or more portable classrooms. Only Jackson County has not announced a schedule to resume classes. Panama City News Herald. Florida Department of Education. Associated Press. Bay County School District officials are asking for donations from the public to help rebuild the district. The campaign is asking for school supplies, clothing and jackets for students, and supplies and gift cards for teachers. Panama City News Herald. Private schools in the Panhandle also took a hit from Hurricane Michael. redefinED. Student victims of the storm are looking for structure and routine. Pensacola News Journal.

Tax referendum: Several schools in the Miami-based charter network Academica are posting fliers on social media sites to let parents know that the Miami-Dade County School District's property referendum will not benefit their schools. The fliers do not directly oppose the tax hike, but do read, “the School Board has not committed to share this money with your child’s school, or any other public charter school, at this time,” as well as pointing out that charter schools are public schools and that 1 in 5 county students attend them. Miami Herald. (more…)

DORAL – Senior Amanda Fernandez walks the halls of Doral Academy Prep in Miami in her neatly tucked red Doral polo, her long, wavy brown hair and tortoise shell glasses doing their best to hide her shy smile.

But there is no hiding – even in a school of 1,700 overachievers – when everyone knows who you are.

She’s a brain.

She’s a beast.

Amanda’s fellow students revere her. Top athletes are intimidated by her. Everyone can recite her accomplishments. 4.0 GPA. Perfect score on the ACT. And they all know the four colleges she was accepted by – Harvard, Stanford, MIT and Princeton.

“She’s the Michael Jordan of Doral,” said principal Carlos Ferralls, who made a bigger deal of each acceptance letter than any sports standout at his school.

The star treatment took some getting used to, but Amanda has always been easy to approach and humble.

“Juniors especially will come up and ask me for tips on how to get into their dream school,” she said. “They see it as more attainable, I guess, because they see me. It’s not that far out of reach.”

The second and youngest child of Cuban immigrants, Amanda grew up knowing how much her parents sacrificed to move to the U.S. before she was born.

“They started from zero twice,” she said. (more…)

School security: St. Petersburg officials reverse themselves and say they will not take 25 police officers off the streets to work as resource officers in the city's elementary schools. City officials point to the cost, more than $3 million, and a reluctance to remove officers from their beats. The decision means the Pinellas County School District will hire security guards for those roles until the district can expand its own police department. Tampa Bay Times. WFLA. The Flagler County School Board approves an agreement with the sheriff to split the $1.8 million cost to increase the number of resource officers in schools to 13. Flagler Live. WJXT. A majority of Lake County students want the school district to arm school personnel, reinforce locks and doors in schools and integrate a mental health curriculum into their classes, according to a survey conducted by a student advisory committee. Daily Commercial. The Sarasota County School Board's creation of an independent police force gets debated further at a Sarasota Republican Club meeting attended by supporters and critics of the decision. Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

School security: St. Petersburg officials reverse themselves and say they will not take 25 police officers off the streets to work as resource officers in the city's elementary schools. City officials point to the cost, more than $3 million, and a reluctance to remove officers from their beats. The decision means the Pinellas County School District will hire security guards for those roles until the district can expand its own police department. Tampa Bay Times. WFLA. The Flagler County School Board approves an agreement with the sheriff to split the $1.8 million cost to increase the number of resource officers in schools to 13. Flagler Live. WJXT. A majority of Lake County students want the school district to arm school personnel, reinforce locks and doors in schools and integrate a mental health curriculum into their classes, according to a survey conducted by a student advisory committee. Daily Commercial. The Sarasota County School Board's creation of an independent police force gets debated further at a Sarasota Republican Club meeting attended by supporters and critics of the decision. Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

A school deputy's pension: The Broward County sheriff's deputy who took cover outside Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School and waited while 17 people were shot to death is now receiving an $8,702.35-a-month-for-life pension from the state. Scot Peterson, 55, retired under fire eight days after the shootings in Parkland Feb. 14. Sun-Sentinel.

Charter schools: Sarasota County School Board members deny an application from a controversial charter school company. The plan to put Pinecrest Academy in the Palmer Ranch area drew an organized protest from people who criticized Academica, the management company behind the charter school. Board members framed their decision on the larger issue of public education's future, and also made the distinction between Miami-based Academica and the homegrown charters already in the county. “I don’t think it’s a good use of our tax dollars to turn it around and give it to a for-profit company that’s out of the county,” said board member Shirley Brown. The company is expected to appeal the decision to the state appeals commission. A second charter school application, for the K-5 Dreamers Academy with an English-Spanish immersion program, was withdrawn. Sarasota Herald-Tribune. redefinED. After 22 years of operation, the Escambia Charter School is closing at the end of the school year. The school in Gonzalez has struggled financially for years because of declining enrollment, according to school district officials. WEAR. WKRG. NorthEscambia.com. (more…)

Hope operators: Two charter school companies have been named the state's first "Hope operators" in a unanimous vote by the Florida Board of Education. Somerset Academy, managed by Miami-based Academica, and IDEA Public Schools of Texas will now have access to low-cost loans for facilities, state grants, a streamlined application process and exemptions from some state laws if they apply to open "Schools of Hope" within five miles of persistently low-performing public schools. Somerset based its application on the work it's done since taking over the Jefferson County School District, and IDEA puts on emphasis on college preparation. IDEA has already identified Tampa and Jacksonville as possible locations for schools. redefinED. Tampa Bay Times. Politico Florida.

Hope operators: Two charter school companies have been named the state's first "Hope operators" in a unanimous vote by the Florida Board of Education. Somerset Academy, managed by Miami-based Academica, and IDEA Public Schools of Texas will now have access to low-cost loans for facilities, state grants, a streamlined application process and exemptions from some state laws if they apply to open "Schools of Hope" within five miles of persistently low-performing public schools. Somerset based its application on the work it's done since taking over the Jefferson County School District, and IDEA puts on emphasis on college preparation. IDEA has already identified Tampa and Jacksonville as possible locations for schools. redefinED. Tampa Bay Times. Politico Florida.

School security: An increase of nearly $100 million in the state budget for school security probably isn't enough to put an armed resource officer in every school, according to a report from the Florida Association of District School Superintendents. The superintendents are asking the Florida Board of Education to support their request that they be allowed to use the $67 million that's in the so-called guardian program to train and arm school personnel, much of which will likely go unspent because many districts oppose the idea. News Service of Florida. The Palm Beach County School District expects to receive $6.1 million from the state as part of the new law requiring resource officers in every school. District officials say that will be enough to hire 75 officers and cover every school. Palm Beach Post. Brevard County school officials expect to get $2.4 million from the state, but say the cost of putting an officer in every school will be $7.8 million. Florida Today. U.S. Rep. Gus Bilirakis, R-Palm Harbor, asks Attorney General Jeff Sessions to direct $75 million in the federal spending bill toward putting police officers into schools. Gradebook. School board in Martin and Leon counties vote to allow only trained law enforcement officers to carry guns in schools. TCPalm. Tallahassee Democrat. WFSU. The Sarasota County Sheriff's Department is looking for 14 candidates to become school resource officers at 12 elementary schools in the unincorporated areas of the county, at a cost of $1.1 million. Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Bradenton Herald. School security will receive extra funding if Marion County voters renew a 1-mill property tax that was approved in 2014 to provide $15 million a year for more teachers and for art, music, physical education and vocational programs. Ocala Star-Banner.

Extension denied: Oscar Patterson Elementary School won't get an extra year to turn around its string of failing grades, the Florida Board of Education decides. Bay County School Superintendent Bill Husfelt appealed to the board for an extra year to get the school's grade up to a C, so a decision on whether to close the school or turn it over to an outside operator could be delayed. Principal Darnita Rivers called the state's decision “disappointing but not discouraging.” Panama City News Herald. WMBB. (more…)

Florida lawmakers have mounting concerns about the finances of a rural district that recently converted its long-struggling public schools into the state's first all-charter system.

In recent weeks, state House committees have heard multiple perspectives on Somerset Academy in Jefferson County.

Community representatives said the charter network worked to earn their trust. Students said they're happy with a new culinary lab. Somerset officials highlighted the new teacher pay plan, the most generous in the state.

But there are complications. And many of them have to do with the finances of the school district, now staffed with a skeleton crew.

House Education Appropriations Chairman Manny Diaz, R-Hialeah, had representatives from Somerset and its management company, Academica, take questions at the end of a committee hearing this week.

They described a tricky transition. They said the charter schools have taken out multi-million-dollar loans while they wait for federal funds. They've poured millions of dollars into capital expenses, from technology upgrades to new buses. And they've overdrawn accounts when the district was slow to hand over state funds.

In the years leading up to the charter takeover, the Jefferson County district hemorrhaged hundreds of students and millions in funding. It went through two rounds of emergency state intervention. Several committee members asked why the district wasn't doing more to help the charter schools manage the transition. (more…)

'Schools of Hope' rules: No charter school companies have yet applied to the Florida Department of Education to become "Schools of Hope." Part of the reason is that no rules have been established for the program, which offers financial incentives for charter schools to move into areas where traditional public schools have struggled persistently. Adam Miller, the director of the state’s school choice office, says the first round of rules is expected to be published in time for the Florida Board of Education to consider at its November meeting. redefinED. The state Board of Education will wait until its next meeting Oct. 18 to announce the public schools that will receive $2,000 more per student under the "Schools of Hope" legislation. The Legislature set aside $51.5 million for up to 25 schools, and 50 applied. Gradebook. No charter school conversions are on the agenda for next week's Florida Board of Education meeting. redefinED.

'Schools of Hope' rules: No charter school companies have yet applied to the Florida Department of Education to become "Schools of Hope." Part of the reason is that no rules have been established for the program, which offers financial incentives for charter schools to move into areas where traditional public schools have struggled persistently. Adam Miller, the director of the state’s school choice office, says the first round of rules is expected to be published in time for the Florida Board of Education to consider at its November meeting. redefinED. The state Board of Education will wait until its next meeting Oct. 18 to announce the public schools that will receive $2,000 more per student under the "Schools of Hope" legislation. The Legislature set aside $51.5 million for up to 25 schools, and 50 applied. Gradebook. No charter school conversions are on the agenda for next week's Florida Board of Education meeting. redefinED.

'Schools of Excellence': Six hundred and forty Florida schools in 44 counties are designated by the Florida Department of Education as "Schools of Excellence." The designation allows the schools to calculate class size by a schoolwide average, set daily start and finish times separate from the district, ignore the state’s minimum reading requirements, earn points toward certification renewal, and gives them greater latitude in hiring and budget decisions for the next three years. Here are the lists for elementary, middle, high and combination schools. Gradebook.

Ever since Donald Trump became president, opponents of school choice have tried to tie charter schools, vouchers and scholarship tax credits to the polarizing politician.

A new public opinion survey suggests those tactics might not be working as intended.

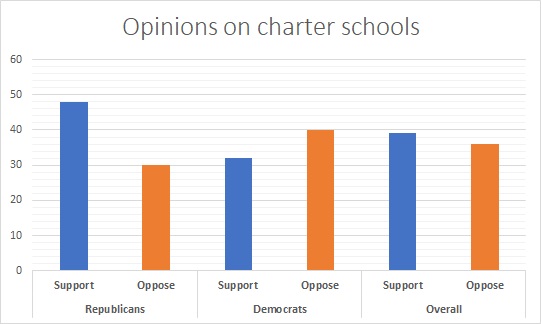

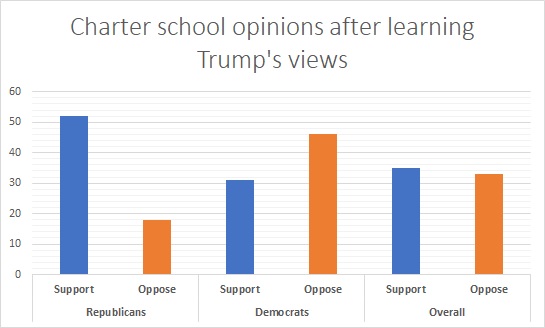

Survey researchers with Education Next asked questions about two school choice policies two ways. Half the respondents answered basic questions about whether they supported tax credit scholarships or charter schools. The other half were asked the same questions, after being told Trump supports the policies.

Even after a sharp drop, charter school supporters still outnumber opponents, according to the latest Ed Next poll.

Associating the policies with Trump didn't change overall support for either policy. But it did tend to polarize issues. Support among Democrats went down, while support among Republicans went up.

Hearing about President Trump's views doesn't change overall charter school support. But it widens the partisan divide.

The poll confirms something school choice advocates saw on the ground during last year's elections. (more…)