The students at Mangrove School routinely visit nature parks and beaches. More than half the students beyond preschool use school choice scholarships.

This is the latest in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

SARASOTA, Fla. — At a nature park bedecked by oaks and palms, a teacher at Mangrove School mimics a wolf call through cupped hands, signaling to scattered students that it’s time to breeze over. “Let’s greet the day,” the teacher says. They all join hands, then take turns facing east, south, west, and north as their teacher offers thanks. To the rising sun. The palms and coonti. The manatees and crabs. Even to the soil.

So class begins at another choice school that defies stereotypes – and conjures possibilities.

On the one hand, Mangrove School is just another one of 2,000 private schools that accept Florida school choice scholarships. On the other, its mission to “honor childhood,” “promote world peace” and “instill reverence for humanity, animal life, and the Earth” is impossible to square with a pernicious myth – on the policy landscape, the equivalent of an invasive species – that school choice is being rammed into place by forces that progressives find nefarious.

“I hear that, and I look around here, and I think it’s very strange,” said Mangrove School director Erin Melia, a former chemist with a master’s degree in education. “I would think it (the perception) would be the opposite. The people most in need of choice are the people left behind.”

Mangrove School started as a play group 18 years ago. Now it has 43 students from Kindergarten to sixth grade, including eight home-schoolers who attend part-time. Nineteen of 35 full-timers use some type of school choice scholarship, most of them the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for lower-income students.*

“We’re just trying to be available to as many families as possible,” Melia said.

That’s a standard view among private schools participating in Florida choice programs, including plenty of “alternative” schools. (Like this one, this one, this one and this one). Those private schools serve more than 100,000 tax credit scholarship students alone. Their average family incomes barely edge the poverty line, and three in four are children of color. Yet the narrative about conservative cabals feels as entrenched as ever.

Blame Trump and the media.

Last March, six weeks after he was inaugurated, the most polarizing man on the planet visited an Orlando Catholic school and held up Florida school choice scholarships as a national model. Just like that, they became a bullseye. In subsequent months, The Washington Post, The New York Times, NPR, Scripps, ProPublica, Education Week and Huffington Post all took aim. Every one of them prominently mentioned the connection to Trump and/or Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. Ditto for the Orlando Sentinel, which punctuated the year with a hyperbolic series that attempted to portray the accountability regimen for private schools as broken.

Not a single one of those stories offered a nod to the fuller, richer history behind school choice. Or to its deep roots on the left. Or to the diverse coalition that continues to support it. So, again, a reminder: (more…)

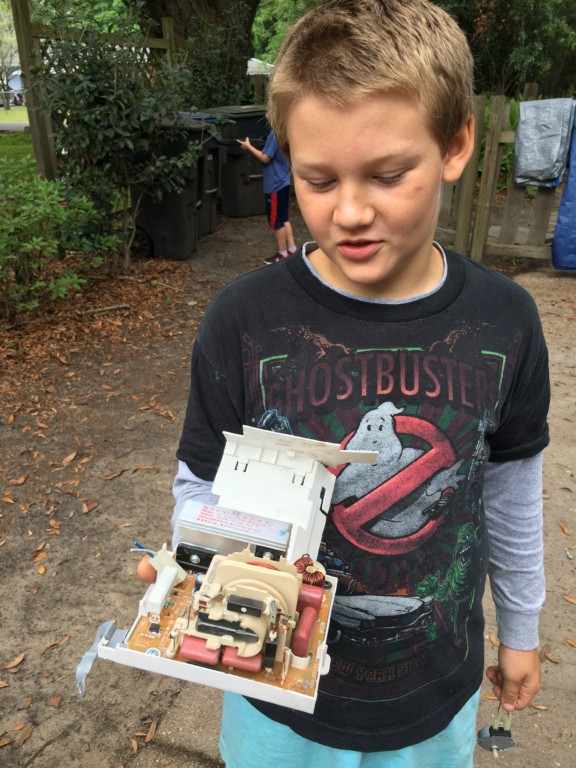

Cyrus Grenat, 10, had fun liberating this component from some gizmo during his "Taking Things Apart" class at the Magnolia School in Tallahassee, Fla. Cyrus attends thanks to a school choice scholarship.

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

With a few deft twists of a screwdriver, Cyrus Grenat, 10, detached one gizmo from an old microwave and another from a vacuum cleaner. At The Magnolia School in Tallahassee, Fla., this is school work.

Cyrus isn’t tested or graded in “Taking Things Apart,” an elective of sorts where out-of-commission radios, smart phones and other gadgets are sacrificed to curiosity.

His tiny private school doesn't do those things. It doesn’t assign much homework either. But once Cyrus gets home, the kid with the gears-turning grin and Ghostbusters T-shirt is planning to blow torch the copper out of one of his liberated components, and see if the other can be retrofitted for use in a remote-controlled car.

“It’s just fun,” Cyrus said. “I learn what’s in stuff, and how stuff works.”

With school choice in the national spotlight like never before, kids like Cyrus and schools like Magnolia could offer a lesson in how vouchers, tax credit scholarships and education savings accounts work.

And who benefits.

The K-8 school in a leafy, working-class neighborhood resists political labels. (I wish we all did.) But every year, its 60 or so students “adopt” a family affected by HIV. Its middle schoolers participate in a camping trip called EarthSkills Rendezvous. Nobody has issues with which bathroom the transgender student uses, or the school’s enthusiastic participation in National Screen-Free Week.

“We are definitely different,” said director Nicole McDermott, in an office barely bigger than Harry Potter’s bedroom under the stairs. “There are kids on the playground right now who are neurotypical, playing with kids who have autism, with kids who have social issues, with kids who have all kinds of differences. We are inclusive and diverse.”

School choice makes it even more so. The Magnolia School participates in three private school choice programs – the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for low-income students, the McKay Scholarship for students with disabilities, and the Gardiner Scholarship, an education savings account for students with special needs such as autism and Down syndrome.* About half the students at Magnolia use them.

That has made the school and its approach accessible to a wider array of families, said Susan Smith, the school’s founder. They, in turn, have enriched the school.

“This gives us the opportunity to reach further outside our little walls, so that our community reflects more of the community our children are going to grow up in, and work in, and make their families with,” said Smith, who has master’s degrees in humanities and elementary education. “It’s part of learning. Not just who you meet, and know, but who you solve problems with, and grow up with.”

The dominant narrative about choice would have America believe it’s a boon for profiteers, a crusade for the religious right, an ideological assault on a fundamental pillar of democracy. But if critics, particularly on the left, took a closer look, they’d see a more lively story – and one that has always included progressive protagonists. “Alternative schools” like Magnolia are among them, and there’s no reason why, with expanded choice, an endless variety of related strains couldn’t bloom. (more…)

To help children grow into independent, compassionate adults, Suncoast Waldorf and other Waldorf schools emphasize art, a reverence for the natural world, a do-it-yourself resourcefulness. They like to have fun too. (Photo courtesy of Suncoast Waldorf.)

This is the latest post in our series on the diverse roots of school choice.

If the Suncoast Waldorf School in Palm Harbor, Fla. is part of a right-wing plot, it’s good at hiding it. Its students cultivate a “food forest.” Its teachers encourage them to stomp in puddles. Its parents sign a consent form that says, I give permission for my child, named above, to climb trees on the school grounds …

And yet, the unassuming, apolitical little school is solidly school choice. Sixteen of its 60 students in grades K-8 last year used tax credit scholarships to help defray the $10,000 annual tuition. And to those familiar with the century-old vision that spawned the Waldorf model – a vision whose first beneficiaries were the children of cigarette factory workers – there’s nothing unusual about it.

School choice scholarships make Waldorf “more accessible to a diverse group of families,” said Barbara Bedingfield, the school’s co-founder. “This is what we want.”

“Alternative schools” like those in the 1,000-strong Waldorf network help upend myths about choice being hard right. This small but thriving corner of the education universe is especially resistant to labels, but there is a nexus between many of these schools and ‘60s-era, counter-culture reformers like John Holt (think “unschooling”) and Paul Goodman (think “compulsory miseducation”).

“Thirty-plus years ago, school choice was almost entirely a cause of the left,” is how writer Peter Schrag described it in 2001, writing for The American Prospect. “In the heady days of the 1960s, radical reformers looked toward the open, child-centered schools that critics like Herb Kohl, Jules Henry, Edgar Friedenberg, Paul Goodman, and John Holt dreamed about. Implicitly, their argument had the advantage of celebrating American diversity and thus obviating our chronic doctrinal disputes about what schools should or shouldn't teach.”

Then and now, the contrarian outlooks of this species of ed reformer are often libertarian and left, both embracing of “progressive” goals and distrustful of government’s ability to deliver. Generally speaking, they aren’t fond of government-dictated standards, testing, grading, grade-level configurations or anything else subject to imposed uniformity. But they are willing to consider the potential of tools like vouchers to give parents the power to choose schools that synch with their values.

Suncoast Waldorf sits on two acres of live oaks, a leafy oasis off a busy road in Florida’s most urbanized county. It blossomed 17 years ago, just as the Sunshine State began blazing trails on the school choice frontier.

To help children grow into independent, compassionate adults, it emphasizes art, a reverence for the natural world, a do-it-yourself resourcefulness. Standardized testing is out (except for what’s required by state law for the scholarship program). So are letter grades and iPads. So is Common Core. (more…)

The students at the City of Palms Charter High School in Fort Myers, Fla., had good reason to be excited. In a few hours, buses would take them to Howl-O-Scream at Busch Gardens in Tampa. The annual trip rewards students who come to school regularly during the first months of the school year and complete some of their courses.

Math teacher Keisha Jackson helps one student at Palm Acres Charter High School while others complete online coursework.

For many students at City of Palms and a growing array of similar schools, that’s no small feat.

Charter schools like it are growing to fill a vaguely defined, little-studied and often-overlooked niche in Florida’s increasingly diverse education landscape. They carry descriptors like "dropout prevention," "alternative schools," and "credit recovery."

In plain terms, they are schools of last resort. They cater to students who dropped out or at risk of doing so, or who have failed courses or “aged out” of traditional high school. They use blended or online lessons to help students rack up credits. The goal is for them to make up for lost time, and leave with a standard diploma.

As the principal, Sarah White, moved through the warren of computer desks inside City of Palms' main campus, she asked students: "Everybody get their five quizzes" for the day? If they have, they're on track.

City of Palms targets students aged 16-21. When students enroll at the school, or at a new, second campus in nearby Lehigh Acres, they receive a transcript, which lists the courses they've completed and the courses they need to graduate. Using the Apex online curriculum, they take their courses one at a time, immersing themselves in a single subject until they pass the final exam and are cleared by their teachers. Finishing a course can take about a month.

"I've had kids finish a P.E. class in a week. I've had kids finish English in two months," White said. "The biggest thing is making them accountable for their education."

The classrooms contain large banks of computers, with teachers offering help to students who need it. There are no class changes in the halls, and there is no cafeteria. When students arrive, for morning or afternoon sessions (another common feature of credit recovery charters), they're free of distractions.

While there have long been alternative schools aimed at students who have fallen behind, City of Palms is part of a relatively new breed of alternative charter schools that specialize in credit recovery. The rise of credit-recovery programs, aided by the growth of online learning, is only beginning to get attention from education researchers.

Earlier this week, University of Illinois Professor Chris Lubienski penned a thoughtful piece on charter schools and social justice. His central concern was markets could undermine the social justice aims held by many charter school advocates. Rather than focusing on providing quality education, Lubienski asserts charter schools may be self-selecting the best students and, in particular, weeding out the most disadvantaged students.

Earlier this week, University of Illinois Professor Chris Lubienski penned a thoughtful piece on charter schools and social justice. His central concern was markets could undermine the social justice aims held by many charter school advocates. Rather than focusing on providing quality education, Lubienski asserts charter schools may be self-selecting the best students and, in particular, weeding out the most disadvantaged students.

While the concerns are valid, the evidence against charter schools is scant and anecdotal and does not allow anyone to draw broad conclusions.

For example, Lubienski cited a recent story from the New York Daily News that showed the Success Academy charter school network has higher suspension rates than surrounding district schools. The anecdote highlighted a special needs student who had difficulty reading and threw temper tantrums in school – which included physically attacking a teacher and throwing objects. Ultimately that family withdrew from the school – something they wouldn’t have been able to do in a traditional public school without a lawyer or school choice – because the mother was “tired of fighting” with school officials.

In another case, Success Academy admitted it didn’t have the means to comply with a special needs student’s Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and recommended the student be transferred to a public school that specialized in special needs education. The parent ultimately decided to stay and push the school to follow the IEP.

Suspensions, counseling and repeated parent-teacher meetings would have to be the most passive aggressive means of getting rid of bad students and probably not all that effective. A more effective means might simply be to expel the students outright. (more…)

Editor's note: Dionne Ekendiz founded the Sunset Sudbury School in South Florida. In her own words, here's why she did it.

I always wanted to become a teacher and make a difference in the lives of children. I truly believed in public education and wanted to be part of making it better. But like many “smart” students, I was dissuaded from that career path, especially by my math and science teachers. They encouraged me to do something “more” with my life, so I went off to MIT and pursued a degree in engineering. After 12 years as an engineer, computer programmer, and project manager in the corporate world, I finally had the confidence and courage to make a change. Others thought I was crazy to leave a great career, but I was driven to pursue my own passion.

I entered a master’s of education program and sought to get the most of my experience there. When I heard about a professor who was conducting research in the “best” public schools in the area, I volunteered to be his graduate assistant. This took me into the schools twice a week. I loved working with the students, but there were things I didn’t like about the environment. One of the most disturbing was how teachers and aides would yell at students to “stay in line” and “don’t talk” in the hallways. Those were the times that schools felt most like prisons to me. But still, I believed a good teacher could learn to control his/her students in a more humane way, so I didn’t let it bother me so much.

I entered a master’s of education program and sought to get the most of my experience there. When I heard about a professor who was conducting research in the “best” public schools in the area, I volunteered to be his graduate assistant. This took me into the schools twice a week. I loved working with the students, but there were things I didn’t like about the environment. One of the most disturbing was how teachers and aides would yell at students to “stay in line” and “don’t talk” in the hallways. Those were the times that schools felt most like prisons to me. But still, I believed a good teacher could learn to control his/her students in a more humane way, so I didn’t let it bother me so much.

A year into my education program, I gave birth to my first child. Watching her grow and learn on her own, especially during her first years, made me see the true genius inside her. Indeed, it is a genius that exists in all children. She was so driven to master new skills like walking, talking, and feeding herself. I was always there with love, support, and encouragement, but my instincts told me to stay out of her way as much as possible and let her own curiosity guide her. Because of my own experiences with schooling and well-meaning teachers, I was determined to let my daughter make her own choices. I knew that with curiosity and confidence intact, she could do and be anything she wanted to.

It slowly dawned on me that everything I was learning about teaching was contrary to the philosophy I was using in raising my own daughter. The goal of teachers, in the traditional setting, is to somehow stuff a pre-determined curriculum into students’ heads. Some teachers do it more gently than others and make it more fun, but the result is the same. Teachers must stifle their students’ own interests and desires to meet the school’s agenda. Simply put, regardless of how nice a teacher is, s/he must coerce students into getting them to do what s/he wants them to do. What I was once willing to do to other people’s children, I wasn’t willing to do to my child. That was a huge wake-up call for me. (more…)