Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey told Arizona lawmakers earlier this year: "Send me the [school choice] bills, and I’ll sign them.” On Friday, they heeded his call.

The state’s lawmakers expanded eligibility for the Empowerment Scholarship Account program to all students in the state at the conclusion of the 2022 legislative session. Previously, approximately one-quarter of Arizona students were eligible to participate.

Also during the 2022 session, the Arizona Legislature substantially increased K-12 funding for public schools, and by a two-thirds vote, suspended an aggregate expenditure limit that would have prevented districts from spending money already in their possession.

The usual suspects will decry this session as “destroying Arizona public education” but actually what it represents is the next logical step in an experiment in education freedom.

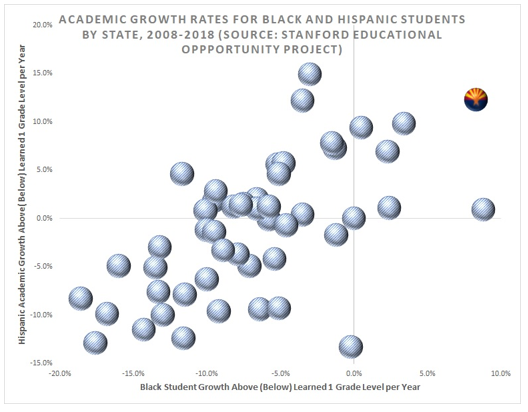

It is well worth noting that a great many indicators demonstrate that Arizona’s experiment with giving educators the opportunity to open new schools and in offering families the opportunity to choose among them was going quite well before the pandemic. I don’t think Arizona would be willing to trade places with any other state on the academic growth of Black and Hispanic students shown between 2008 and 2018:

Arizona already has three universal education programs: school districts (which receive the highest amount of spending per pupil on average), charter schools (which educate a higher percentage of students than in any other state); and the original scholarship tax credit program. Arizona’s other choice programs are either means-tested or like the ESA program have served special student populations.

Arizona already has three universal education programs: school districts (which receive the highest amount of spending per pupil on average), charter schools (which educate a higher percentage of students than in any other state); and the original scholarship tax credit program. Arizona’s other choice programs are either means-tested or like the ESA program have served special student populations.

The original scholarship tax credit program has universal eligibility but only raised approximately one-sixth of the amount of funds raised by the largest of Arizona’s 207 school districts last year. In total, Arizona’s K-12 tax credits raised about $250 million last year, which is more than half the money received by the largest school district.

The Empowerment Scholarship Account program is funded on a formulaic basis like districts and charter schools, and thus could become larger than the tax credit programs over time.

Much wrangling is sure to follow. Assuming the expansion survives the attacks of opponents, I can safely predict the following:

Arizona public schools are not going anywhere. Their funding is guaranteed in the Arizona Constitution, their level of funding is already at a historic high, and will go higher still.

No “mass exodus” of students will occur out of Arizona’s other three other education models with universal eligibility. There are about 1.2 million public school students in Arizona, and the last survey of private schools that I am aware of found 26,000 available private school seats. That’s about 2.1% of students for those scoring at home.

Parental demand for private education, or possible lack thereof, will continue to shape the K-12 space in Arizona.

The Empowerment Scholarship Account program, of course, has many uses other than private school tuition, so we’ll have to see how things develop. As for learning pods, thousands of adventurous parents and educators already have found a way to “pod up” with students accessing public funding.

What is most important about any private choice program is not the number of actual participants, although it is quite important to them. The most important aspect of private choice programs is who can participate.

In other words, what is the funded eligibility of the program? This law will provide every student in Arizona a new education option and will be there if their families conclude they need it.

That is as it should be. All Arizona families pay their taxes, all deserve access to every K-12 program.

An education tool with the flexibility of the ESA creates new opportunities for teachers, families, and students. Arizona educators took their previous set of tools, and in a slow but steady process of co-creation, shaped a K-12 system with the amazing potential for expansion and replication. Parents demanded more of some schools, and either depopulated or closed others.

The best is yet to come.

The Orme Private School in Mesa, Arizona, one of 451 private schools in the state serving more than 66,000 students, was founded by Charles Orme Sr. in 1929. Orme’s dream was to create a friendly, strong children's collective that would allow students to reach academic and personal heights, developing emotionally and spiritually.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Wednesday on azmirror.com.

A proposal to let all 1.1 million Arizona students use taxpayer-funded vouchers to attend private school passed the Arizona House of Representatives Wednesday after two Republicans who had opposed previous efforts to expand the program changed their position.

The Empowerment Scholarship Account program, commonly referred to as ESAs, has been narrowly implemented since its creation in 2011. Eligible students include children attending failing public schools, children whose parents are in the military, kids who are in the foster care system and students living on Native American Reservations. Currently, roughly 11,800 students are enrolled and receive the

voucher money.

But House Bill 2853 would allow every Arizona student to get an ESA account — including those who already attend private schools — to pay for their education.

Legislative budget analysts have said that only an estimated 25,000 students would likely take advantage of the expanded eligibility.

ESA dollars can be spent on anything a student needs, from tuition for a private school to tutoring or to homeschooling materials.

“If you are a millionaire or a billionaire and your kid goes to private school today, you will now receive a check to subsidize them,” Rep. Reginald Bolding, D-Laveen, said. “We have one of the lowest per-pupil funding ratios in this country, and what we chose to do is to make it even worse by taking more resources out of our general fund.”

To continue reading, click here.

Redeemer Christian School in Mesa, Arizona, one of 451 private schools serving more than 66,000 Arizona students, bases its educational approach upon the classical teaching model known as the Trivium, dividing the academic life of a student into three stages reflecting the student’s natural capacity for certain types of learning.

Editor’s note: This Q&A about Arizona’s House Bill 2853 appeared last week on the Goldwater Institute’s website.

The Arizona Legislature has unveiled an ambitious plan to put K-12 students and parents first. Sponsored by House Majority Leader Ben Toma and co-sponsored by over two dozen of his peers, HB 2853 would open the doors to educational opportunity for kids throughout the Grand Canyon State.

While the bill has already cleared its first hurdle—passing the House Ways and Means Committee — it’s worth digging into what exactly the legislation does, and doesn’t do, for Arizona families.

What is the purpose of the legislation?

HB 2853 expands eligibility for the Arizona Empowerment Scholarship Account program to every family in the state. Families who participate would receive over $6,500 per year per child for private school, homeschooling, “learning pods,” tutoring, or any other kinds of educational service that would best fit their students’ needs outside the traditional public school system.

Any child who wishes to opt out of their local public school (or who already has) would be allowed to join the ESA program under the bill.

Many families simply lack the financial resources to pursue private or homeschooling options, while others have made financial sacrifices and shoulder the expense of private school tuition or paying for homeschool supplies. These families are all currently entitled to send their child to a public school (at a cost of over $10,000 per year to taxpayers), regardless of their income.

This bill would ensure that all families have the freedom to choose whatever form of education best fits their child’s needs.

Does this harm existing ESA families or will it crowd out families who are already eligible for the program?

No, this bill places zero new restrictions on any family who is already eligible for the ESA program, including special needs students.

To continue reading, click here.

Arizona’s Empowerment Scholarship Account, administered by the Arizona Department of Education, is funded by state tax dollars to provide education options for qualified Arizona students. The education savings account consists of 90% of the state funding that would have otherwise been allocated to the school district for the qualified student.

Editor’s note: This first-person essay from Arizona mother Cassandra Pacheco was adapted from the American Federation for Children’s Voices for Choice website.

When my child started kindergarten, I noticed he did some things differently from his classmates. He didn’t like to communicate with them, or with his teachers. He hid under desks and wouldn’t come out.

When my child started kindergarten, I noticed he did some things differently from his classmates. He didn’t like to communicate with them, or with his teachers. He hid under desks and wouldn’t come out.

I had a meeting with the leaders at my son’s assigned district school to discuss an Individual Education Plan for my son. I was told he wasn’t “severe” enough to qualify for a special education classroom and we would have to be satisfied with a general education classroom with some special services, such as occupational therapy and a resource room.

But these accommodations just weren’t enough.

We had him evaluated at the end of kindergarten and the diagnosis was autism. A second opinion was the same. Both evaluators told me about Arizona’s Empowerment Scholarship Account, a program from the Arizona Department of Education that gives eligible parents public funding to pursue flexible options for customizing their children’s education. Intended to expand educational opportunity outside of the public school system, it provides funding for a wide range of personalized education expenses, including private school tuition, tutoring services, textbook and more.

Working with my son’s Independent Education Plan team, we were able to update his primary category of disability to autism but decided to give him some time to see if things got better before doing anything else. Finally, at the end of first grade, we decided to apply for the education savings account.

We were approved, and I informed the administrators at his school that we would be moving him to a private school for children with autism. While most of them supported our decision, some did not.

But by this time, I didn’t care; I needed to do what was best for my child, and his district school just wasn’t able to provide for him. The private school, which we were able to pay for with the education savings account, worked well for a year. My son’s communication skills, as well as his social skills, improved.

Then the pandemic hit. We enrolled him in an online private school that offered tutoring, music, parkour, basketball, and other programs. We were able to choose this option because of our education savings account.

Our son has made tremendous strides physically – his running and climbing have improved – and he has improved academically as well. Having the opportunity to choose what is best for our child has been amazing. It has been empowering to have the chance to make a change from what we knew was not working.

That feeling of empowerment is why school choice is so important for families; it gives parents and guardians the ability to make informed decisions that result in better outcomes rather than staying in a school that is not serving their child’s needs.

I try to spread the word about school choice to other parents and help answer their questions. It’s the least I can do since Arizona’s education savings account program helped my child so much.

Arizona started down the choice road back in 1994 when a bipartisan group of legislators passed both a robust charter school law and an open enrollment law forbidding districts from charging tuition and requiring them to have an open enrollment policy.

Arizona started down the choice road back in 1994 when a bipartisan group of legislators passed both a robust charter school law and an open enrollment law forbidding districts from charging tuition and requiring them to have an open enrollment policy.

Subsequently, Arizona lawmakers were the first in the nation to pass a scholarship tax credit statute (in 1997) and an education savings account program (in 2011). Put it all together and a majority of Phoenix area K-8 students attend a school outside their zone, with open enrollment students easily outnumbering other forms of choice.

Happily, Arizona led the nation for student academic growth between 2008 and 2018 overall, for low-income students and for middle-high income students in data compiled by Stanford University. But the state has miles to go in extending choice despite the progress made to date.

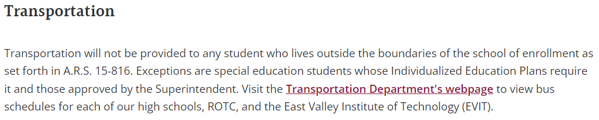

Arizona’s student bus system largely still runs as if it were still 1993, with buses running in attendance zones that students increasingly ignore. It is still common for districts to make transportation the sole responsibility of the family for open enrollment students.

As evidence, here is a statement on the Temple Union High School District’s website.

Last year, the state began a process of modernizing student transportation. Legislators are seeking to further that process this session.

Next: the issue of admissions.

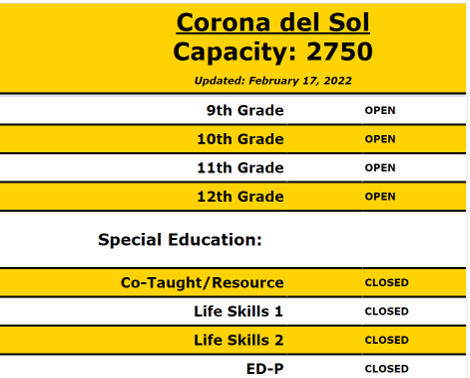

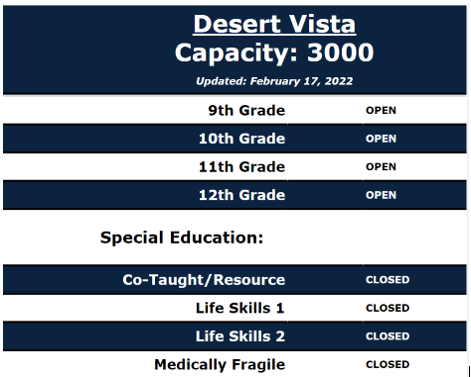

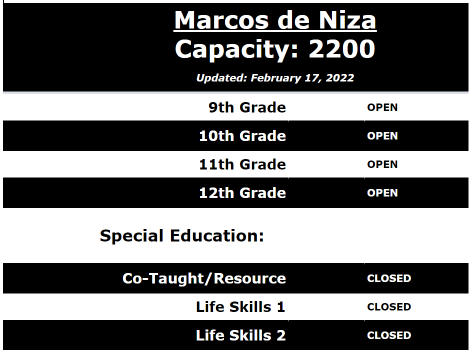

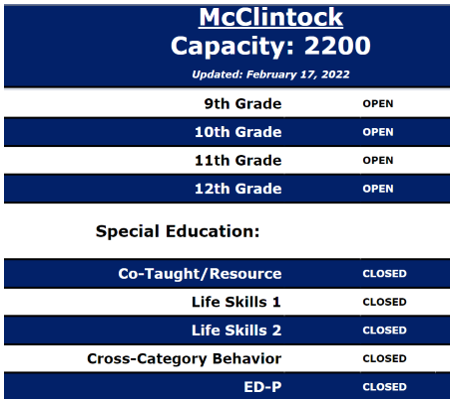

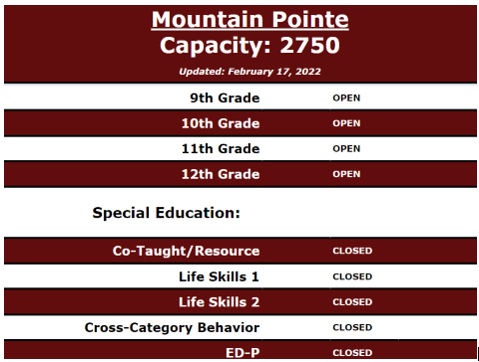

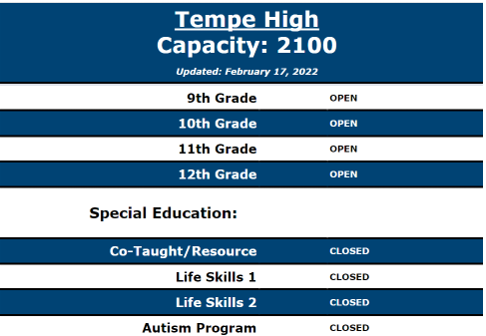

This has been the subject of discussion in the Arizona Legislature and the Arizona State Board of Education over the last year. Again, using the Tempe Union High School District website, see if you can detect a pattern in the availability of open enrollment seats among the district’s six high schools:

You may have noticed that none of the six high schools offer spots to students with disabilities. Tempe Union High School District is far from alone with regards to such practices, which remain common. The justification lies on the logical slide of special needs “programs.” If the “program” is at “capacity,” then your droids will have to wait outside: We don’t serve their kind here.

Federal special education law only guarantees a special needs child the right to attend his or her zoned district school. Federal anti-discrimination statutes may, however, constitute another matter entirely. If a family with a special needs student moves into the attendance zone of any of these schools, the schools would in effect expand their special needs programs, whether they were “at capacity” or not.

The district simply chooses not to do so for open enrollment students. “Program capacity” is simply camouflage for “discrimination.”

It also is worth noting that Arizona law forbids discriminating against special needs children in enrollment by either district or charter schools. This law, passed in 2006, created a special needs voucher program but disallowed public school enrollment discrimination against special needs students:

The Arizona scholarships for pupils with disabilities program is established to provide pupils with disabilities with the option of attending any public school of the pupil's choice or receiving a scholarship to any qualified school of the pupil's choice.

The Arizona Supreme Court overturned the voucher program and the program was replaced by an ESA program that survived court challenge. The public-school non-discrimination language was not overturned but has routinely and systematically been ignored for a decade and a half.

It’s long past time for these practices to stop.

I’ve heard that advocates of open enrollment reform are encountering opponents who claim that if you allow open enrollment, then suburban property values will go down.

I’ve heard that advocates of open enrollment reform are encountering opponents who claim that if you allow open enrollment, then suburban property values will go down.

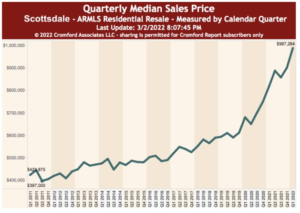

Scottsdale, Arizona, is one of the most active suburban choice areas in the country and a hotbed for open enrollment. In examining the record in Scottsdale, benefits are easy to find, and the theorized harms have failed to materialize.

Arizona has a usually active choice environment, with a majority of K-8 students in the Phoenix metro area attending a school other than their zoned district option. Arizona lawmakers passed open enrollment and a robust charter school statute in 1994 and began passing private choice legislation in 1997.

Arizona’s charter sector is both inclusive and diverse across communities, which is to say, unlike many states, it includes suburban communities. This is crucially important, as it encourages suburban districts like Scottsdale to participate in open enrollment.

Scottsdale Unified has campus capacity to educate 38,000 students, but currently has closer to 20,000 students. Many factors influence enrollment, including real estate prices, fertility trends, and the availability of other school options.

Nine thousand Unified Scottsdale students live within district boundaries and go to schools in other districts. Multiple charter schools have seen strong growth in the district, students can attend other districts through open enrollment, and on a more limited basis, aid to attend private schools can be accessed by families.

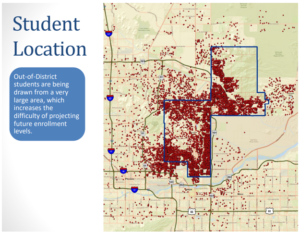

Scottsdale Unified, however, partially made up for the 9,000-student loss by enrolling 4,667 students through open enrollment during the 2019-20 school year. This graphic below, from a demographic report prepared for the district, depicts the location of enrolled students.

Altogether, almost one in four Scottsdale Unified students live outside district boundaries. Did the opening of all those charter schools and the lowering of the gate for open enrollment damage property values in Scottsdale?

Altogether, almost one in four Scottsdale Unified students live outside district boundaries. Did the opening of all those charter schools and the lowering of the gate for open enrollment damage property values in Scottsdale?

Apparently not.

The diversification of K-12 opportunities may have helped property values in Scottsdale. It is certainly difficult to find evidence that property values have been harmed in any way.

Access to high quality schools should not be rationed through the mortgage market, nor kept as an unnecessarily scarce commodity. Freeing educators to create new schools and families to select between them creates opportunities for families and teachers.

Empowered Minds Academy is an in-home microschool in Maricopa, Arizona, based on the Prenda model of 5-10 students led by mentors, or guides, who engage children in collaborative activities and creative projects.

Editor’s note: This post from Mike McShane, director of national research at EdChoice and a reimaginED guest blogger, appeared Thursday on forbes.com.

The Roman philosopher Seneca is quoted as saying that “luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.”

When the coronavirus hit Arizona and parents were looking for options outside of their closed traditional public schools, they were lucky to find a proliferating network of microschools. But that lucky moment was years, if not decades, in the making.

In a new paper for the Manhattan Institute, I examine the phenomenon of microschooling in Arizona.

After hearing from several parents who found microschools to be a godsend after they grew frustrated watching their school boards and administrators dither and prevaricate on COVID policies, I wanted to answer a basic question: Why here?

To answer that question, we have to look back more than two decades into Arizona education policy.

Starting in the mid-1990s, Arizona pushed for greater school choice, with the legislature passing a charter school law and an open enrollment law, followed just a few years later by one of the nation’s first tax-credit scholarship laws. Over the intervening years, the state has created four more private school choice programs, including a nation-leading education savings account in 2011.

To continue reading, click here.

Arizona’s boom in new schools includes many charter schools, like this BASIS school in Scottsdale.

Editor’s note: This commentary from reimaginED executive editor Matt Ladner appeared Tuesday on Education Next.

“Supply-side progressivism” was the topic of a recent New York Times article by Ezra Klein, citing “Cost Disease Socialism,” a new paper by the Niskanen Center.

“We are in an era of spiraling costs for core social goods — health care, housing, education, childcare — which has made proposals to socialize those costs enormously compelling for many on the progressive left,” Steven Teles, Samuel Hammond and Daniel Takash write in the Niskanen Center paper Klein mentions.

Klein went on to say: There are sharp limits on supply in all of these sectors because regulators make it hard to increase supply (zoning laws make it difficult to build housing), training and hiring workers is expensive (adding classrooms means adding teachers and teacher aides and expanding health insurance requires more doctors and nurses) or both.

“This can result in a vicious cycle in which subsidies for supply-constrained goods or services merely push up prices, necessitating greater subsidies, which then push up prices, ad infinitum,” they write.

Something like that description may also apply to Arizona’s success in spurring academic growth in the pre-pandemic period. Arizona has the largest charter-school sector in the country, serving about 22% of the Grand Canyon State’s public-school students.

Add to that private-school choice programs in the form of scholarship tax credits and education savings accounts, and the result is that the supply of new schools has been relatively unconstrained. This suited Arizona’s needs when choice programs first passed in 1994; at the time, Arizona was a state rapidly growing in population and the existing schools and students were attaining a low-to-average level of academic performance.

To continue reading, click here.

In the latest installment of EdChoice’s “Big Ideas” podcast series, director of policy Jason Bedrick speaks with reimaginED executive editor Matt Ladner about Ladner’s recent report, “Microschools versus Waitlists: A Guidebook for the Innovative Arizona Educator.”

In the latest installment of EdChoice’s “Big Ideas” podcast series, director of policy Jason Bedrick speaks with reimaginED executive editor Matt Ladner about Ladner’s recent report, “Microschools versus Waitlists: A Guidebook for the Innovative Arizona Educator.”

At the top of the interview, Ladner provides a definition of microschools and how they differ from learning pods. He goes on to detail what he’s observed regarding the rise of microschools in his home state of Arizona, a launching pad for education innovation, and what he’s seen first-hand on visits to microschools:

“My instant reaction watching kids do project-based learning was, ‘This looks like a lot of fun … obviously the kids are totally into it."

The interview includes Ladner’s take on why microschools are gaining a loyal following across the country, why this is a great time for education entrepreneurs, and what this groundswell could mean for K-12 education in the future.

You can listen to the interview here.

University High School in Tucson, Arizona, was ranked No. 17 in the nation and No. 2 in the state in the 2021 U.S. News & World Report analysis of the country's high schools.

In an earlier post, I explained why districts don’t tend to replicate or expand high-demand schools. In a word, the reason is politics.

Adults working in low-demand schools, with enrollment well below the design capacity of their buildings, tend to look upon expanding or replicating high-demand district schools in a way not dissimilar from their all-too-common view of charter schools: somewhere on the fear to loathing spectrum.

School district boards are strongly influenced – one might even say easily captured – by incumbent adult interests. When I wrote my previous post, I gave the example of University High School in the Tucson Unified School District. Tucson Unified once was the largest district in Arizona but has shown a consistent trend of shrinking enrollment for decades despite its location in a rapidly growing state.

University High, a magnet school that is housed in the basement of another high school, has been a fantastically high performing-high demand school with a majority-minority student body for many years. The school earned an “A” grade from the state of Arizona and a 10/10 rating from GreatSchools, which in its equity overview stated that disadvantaged students at this school are performing far better than students elsewhere in the state and that the school successfully is closing the achievement gap.

In a reasonable world, we’d figure out how to provide more Tucson kids with the opportunity to attend University High.

Tucson Unified has an abundance of vacant school space, so in a remotely rational world, University High would have its own space, and there would be multiple University High campuses. (Give the people what the waitlists are telling us that they want!) University High, however, does not operate in a rational system, but rather in an urban school district.

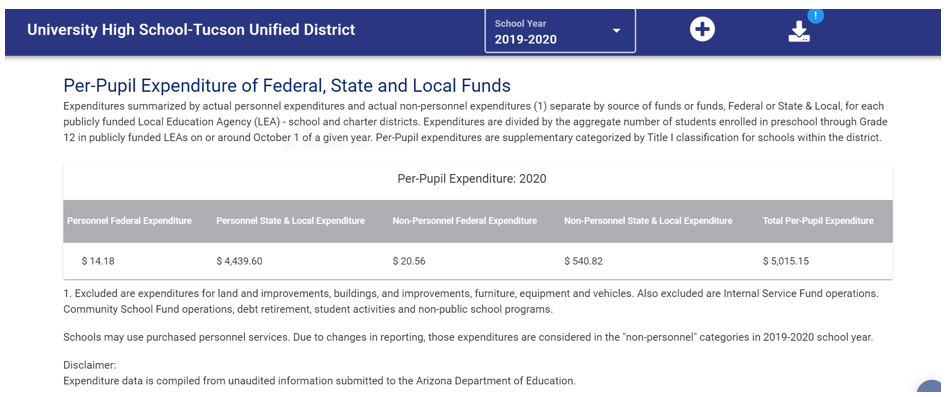

Rather than scaling or replicating University High, the Tucson Unified School District has been systematically starving the school of resources. Tucson Unified spent just under $11,000 per student in 2020 according to the Arizona Auditor General report.

High-schools are more expensive to operate than elementary schools, so we would expect higher spending per pupil in high-schools than elementary and middle schools. Here is the per pupil revenue figure that the TUSD administration reported to the Arizona Department of Education for University High:

So, if you are scoring at home, Tucson Unified has a high demand, high performing school with a waitlist that it keeps in the basement of another school. Self-reported district figures show Tucson Unified provided less than half the per-pupil funding than the district receives on average. It would appear that Tucson Unified is not only keeping University High living under a staircase, it also is keeping it on a financial starvation diet.

Keep this in mind the next time someone attempts to argue that there is “already choice in the district system.” There is some choice in the district system, but organizations don’t often disrupt themselves.