Keith Jacobs II, affectionately called "Deuce," with his parents, Keith and Xonjenese Jacobs. Photos courtesy of the Jacobs family

When our son Keith — affectionately known as “Deuce” — was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at age 3, we were told he might never speak beyond echolalia (the automatic repetition of words or phrases). Until age 5, echolalia was all we heard.

But Deuce found his voice, and with it, a unique way of seeing the world.

He needed to find the right learning environment, with the assistance of a Florida education choice scholarship.

Deuce spent his early academic years in a district public school, supported by an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). Despite the accommodations, learning remained a challenge. We realized that for some, a student’s success requires more than paperwork. It requires community, compassion, and collaboration with the parents.

Imagine having words in your head but lacking the ability to communicate when you need it most. That was Deuce’s experience in public school. His schools gave him limited exposure to social norms and rigor in the classroom. Additionally, through his IEP, he always needed therapy services throughout the school day, which limited his ability to take electives and courses he enjoyed.

His mother and I instilled the importance of having a strong moral compass and working hard toward his social and academic goals. Although we appreciated his time in public school, we knew a change was needed to prepare him for post-secondary education. We applied and were approved for the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities.

Knowing the potential tradeoffs of leaving public school and the IEP structure behind, we chose to enroll Deuce at Bishop McLaughlin Catholic High School in Spring Hill, about 35 miles north of Tampa. We believed the nurturing, faith-based environment would help him thrive. It was the right decision.

Catholic school provided Deuce with the support he needed to maximize his potential. Despite his autism diagnosis, he was never limited at Bishop. He was accepted into their AP Capstone Program. This was particularly challenging, but Bishop was accommodating. The school provided him with an Exceptional Student Education (ESE) case manager dedicated to his success, and he received a student support plan tailored to his diagnosis and learning style. The school didn’t lower expectations; instead, it empowered him to take rigorous coursework with the right guidance.

Any transition for a child with autism will take time to adjust. On the first day, I received a call: Deuce had walked out of class. This was due to his biology teacher using a voice amplifier. The sound overwhelmed Deuce’s senses, and he began “stimming”— rapidly blinking and tapping his hands. Instead of punishing him or ignoring the issue, the staff immediately reached out.

Together, we crafted a Student Success Plan tailored to Deuce’s needs, drawing from his public school IEP without being bound by it. His plan included preferential seating, frequent breaks, verbal and nonverbal cueing, encouragement, and clear direction repetition. For testing, he was given extended time, one-on-one settings, and help understanding instructions.

These adjustments made all the difference.

Throughout high school, Deuce maintained a grade-point average of over 4.0 while taking honors, AP, and dual enrollment courses. Additionally, he was inducted into the National Honor Society and Mu Alpha Theta Math Honor Society while also playing varsity baseball. Because of his success at Bishop, he will continue his educational journey at Savannah State University, where he will major in accounting and continue to play baseball.

Deuce Jacobs earned an academic scholarship to Savannah State University, where he plans to major in accounting and continue playing baseball.

Catholic schools in Florida increasingly are accommodating students with special needs. The state’s education choice scholarship programs have been instrumental in making Catholic education available to more families. Over the past decade, during a time when Catholic school enrollment has declined across much of the nation and diocesan schools have been forced to close, no state has seen more growth than Florida.

At the same time, the number of students attending a Catholic school on a special-needs scholarship has nearly quadrupled, from 3,004 in 2014-15 to 11,326 in 2024-25. Clearly, many families are choosing the advantages of a private school education without an IEP versus a public school with an IEP.

So, I’m puzzled why federal legislation being considered in Congress, the Educational Choice for Children Act (ECCA), includes a mandate that that all private schools provide accommodations to students with special education needs, including those with IEPs.

Although more and more students with special needs are accessing private schools, not every school can accommodate every student’s unique needs (which is also true of public schools). And, as I learned with Deuce, some schools can accommodate students more effectively if they aren’t bound by rigid legal mandates and have the flexibility to collaborate with parents who choose to entrust them with their children’s education.

If the IEP mandate passes, it would prohibit many schools from accepting funds through a new 50-state scholarship program, undermining the worthy goal of extending educational choice options to more families. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has called it a “poison pill” that would “debilitate Catholic school participation.”

Bishop McLaughlin’s willingness to partner with me as a parent not only allowed Deuce to succeed academically but also gave him the dignity and respect every child deserves. IEPs work for many. For others, like Deuce, it takes something more like collaboration to build a path forward together.

Tristan Drummond was born 10 weeks premature with one kidney and enough genetic disorders that doctors gave him a 50/50 chance to turn 1.

He had his first surgery when he was 2 days old and has far exceeded that dire prediction. He will turn 12 in June.

But his lungs are filled with scar tissue, and his left lung tends to collapse. He’s susceptible to colds that lead to pneumonia, and that leads to more scar tissue on his lungs.

Also, Tristan is on the autism spectrum.

“The cherry on top,” said his mom, Danielle.

Tristan is homeschooled and receives the state's Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities. Unless he’s going to a doctor’s appointment or the grocery store with his mom, he spends nearly all his time inside the family’s home in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Yet Tristan’s world virtually spans the globe.

“The scholarship has allowed him to actually have a life,” Danielle said. “It's hard for kids like him because they don't have a lot of outlets. They need those relationships with other kids, and that is a safe way for him to do it. He has friends that he plays with online.”

The scholarship operates as an Education Savings Account (ESA), which allows Tristan’s parents to spend its funds on curriculum and other approved education-related expenses. Art supplies have topped that list during this school year.

The ESA also allows for electronics, which have shaped Tristan’s education and enabled him to have a social circle of about 50 friends whom he’s never met physically yet plays with nearly every day.

Tristan was born with VACTERL, which stands for vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheo-esophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities. Not everyone with VACTERL has all six conditions. Tristan has three.

“It's a nice little combo of rare diseases that just sort of all landed on one kid,” Danielle said.

He was born without a section of his esophagus and a tethered spinal cord.

“He had eight surgeries before his fifth birthday and so many procedures I’ve lost count,” Danielle said.

Tristan had back surgery when he was 6 to correct his spinal cord. That’s when Danielle and her husband, Ashley, used the ESA for a large-screen TV and virtual reality equipment to help Tristan relearn how to walk. They quickly realized the benefits the ESA could have on Tristan’s life.

Virtual reality has been used for nearly 25 years to help people on the autism spectrum learn to communicate and develop job skills. It has helped Tristan improve his cognitive and gross motor skills through occupational and physical therapy. It helped him increase his attention span and developed his hand-eye coordination and core strength. He’s learned how to count and how to exercise.

It has also taken him around the world.

Tristan landed on the moon with the Apollo 11 crew, swam with sharks off the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, and visited Epcot Center and the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.

He’s studied astrophysics and Van Gough and knows everything about the tardigrade, an eight-legged micro-animal that lives in water.

The online game Roblox makes Tristan aware of how his body moves because it tracks a player’s body, eye, and facial expressions. He learned to work with teammates by playing the video game Beat Saber. Gorilla Tag allows Tristan to play tag with his friends, something he could never do in the real world without the risk of getting sick.

Tristan had trouble sleeping at night until Danielle came across Liminal VR, which stimulates different parts of the brain.

“He does his five minutes on there, takes his bath, then he goes to sleep and doesn't have a problem,” Danielle said.

With Minecraft, Tristan has built an entire neighborhood, complete with houses and people living in those houses. He makes videos with his Stickbots and Godzilla figurines.

Everything is relevant to her son’s education, Danielle said. Tristan is learning to code and make videos. He’s learning science and math. Some might see it as unorthodox.

“But he doesn’t fit in a box,” Danielle said.

Tristan responds to electronics. To not have that would be a lost opportunity when it comes to his education.

“This is where it changes into something that can be usable for a career later,” Danielle said. “For kids like Tristan, technology is going to be where their careers, if they have them, are going to be because they have an aptitude for it.

“You hope for him to have a productive life and hopefully be a contributing member of society, and the future of our society is electronic.”

Traditional school wasn’t working for Alexander Luther. The 15-year-old, who has autism spectrum disorder, would get overstimulated and tired toward the end of the 6-hour day. His mother, Sue, a former teacher who had homeschooled her son during the pandemic, knew some well-timed breaks would help him maintain focus so he could learn the life skills he would most need as an adult.

So, Luther designed a home learning plan for him that combined lessons in core subjects with practical skills such as counting money, budgeting, housekeeping, and staying healthy.

“The goal is for him to be as independent as possible,” she said.

Luther, a former military spouse and single mom from Largo, Florida, stopped using Alexander’s Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities to pay private school tuition and started using it to buy the supplies necessary for him to learn at home.

Florida lawmakers passed the Unique Abilities scholarship program in 2014. Formerly known as the Gardiner Scholarship, it provides an education savings account that functions like a restricted-use bank account from which parents direct funds to pay for private school tuition and fees, approved homeschooling expenses, therapies, tutoring and other education-related expenses.

Luther used some of Alexander’s funds to buy a virtual reality headset for physical education. He uses it to play Beat Saber, a rhythm game where players slash colorful cubes with virtual swords as they fly toward them to the beat of fast-paced music. Luther says the game not only provides physical activity but helps prime Alexander’s mind for learning. Small-scale research has suggested that so-called exergaming, which combines virtual reality games and physical exercise, can help younger users improve their performance at specific cognitive tasks.

“VR has come a long way,” said Luther, who used personal funds to buy herself a headset to play Beat Saber and other exergames. “It’s a great workout, and we can do it together. It’s such a great tool. It’s going to be in a lot of schools someday.”

The VR activities also allow him to learn social skills.

“He’s got to learn how to take turns and how to interact with others,” Luther said. “It gives him the space he needs. Nobody’s touching him.”

Luther bought Alexander’s laptop and headset through MyScholarShop, an online purchasing platform for families who have an education savings account. The portal lets parents buy pre-approved instructional materials and curricula without having to pay out of pocket.

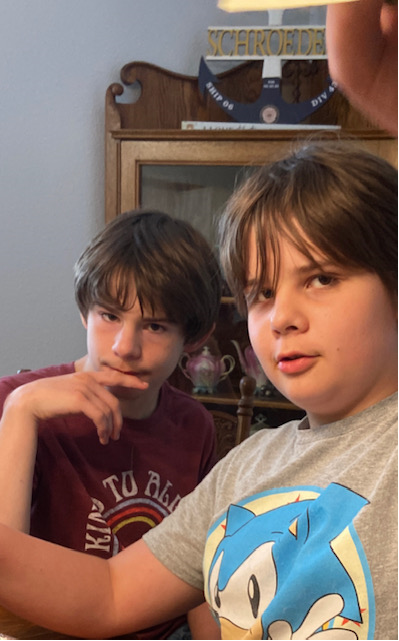

Alexander Luther, left, with younger brother, Miles

A typical homeschool day begins with breakfast after dropping off Alexander’s younger brother, Miles, 13, off at a charter school.

Alexander helps make the toast and jelly and puts away his dishes after he eats. The activity is not only for nourishment but also to teach Alexander the life skills needed to live as independently as possible as an adult.

Next is handwriting practice, followed by instruction on the laptop. Then he takes a break before lunch, when he helps Luther prepare the meal and clean up afterward.

Alexander spends the afternoon on math followed by science, which typically involves projects such as making a lava lamp or growing a plant.

The last part of the day includes Beat Saber or yoga and then winds down with an art project before it’s time to pick up Alexander’s brother from school.

Alexander uses his laptop for learning games and puzzles on ABC Mouse and Starfall sites and for video games that Luther offers as rewards for staying on task and achieving goals.

In the evenings, a therapist certified in applied behavioral analysis comes to the house to help Alexander with self-care skills such as showering. The family’s insurance covers the therapy sessions, but for other families, therapy provided by a certified behavioral analyst is an eligible scholarship expense.

This year, Luther has seen Alexander make progress in math and counting. She uses play money to help teach him addition and subtraction and how that works in real life scenarios. He recently began receiving government disability payments, making money management an even more important skill. Sometimes they dine out so Alexander can practice personal finance skills by recording transactions on Cash App.

The app gives him a place to keep the money he earns from doing simple household chores such as putting away his laundry and cleaning his room.

“If he wants a hamburger or a video game, he can use the app to buy it,” Luther said. The app also keeps a history of transactions so Alexander can evaluate his spending choices and improve his decision-making skills. “I want him to know so no one can take advantage of him,” she said. “I want him to be able to figure out “Did I spend this or did someone take it from me?’ I know he’s never going to be able to be on his own completely, but he needs to be aware.”

Luther said he also has improved his handwriting as well as his patience and focus.

“Getting him just to do that has been a huge improvement,” she said.

Luther said she sees a need for more programs to serve teenagers who can’t go to college or technical school but who need training in job and life skills.

“That’s the school I always wanted to start – how to survive in the world if they don’t want to go to college. We would have fewer dropouts. That’s part of the whole school choice thing, isn’t it?”

Gretchen Stewart focused her dissertation on research that would inform the model for Smart Moves Academy, involving more than 40 experts in brain development, learning, cognition and movement in her quest to assist children with autism. The new school is set to open in 2022.

"There was one event that triggered me to create the private school I had always thought about over my career. It came one day when my son came home and said to me, 'Mom, I’m a weird kid.' That broke me, and for a time, it broke him too. " – Gretchen Stewart

Gretchen Stewart is the founder of Smart Moves Academy, an inclusive private school launching in the Tampa Bay area with a vision to ignite the mind through movement. The school’s model will optimize brain performance through physical activity for lifelong learning, health, fitness, and emotional well-being. Stewart has been named a Drexel Fellow and received a grant from the national non-profit foundation to further develop her plan and open the school in 2022. The school will accept scholarships administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog. Answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Gretchen Stewart

Q. You received your undergraduate degree in political science, government and Spanish at the University of Minnesota - Twin Cities. What were you planning to do at that time and what prompted you to pursue education instead?

A: I dropped out of high school at age 16. Looking back with the understandings I have now, I was at risk for school failure from the start of my school career as a kindergartner. My family background included many risk factors associated with school failure, and the city I lived in had de-facto segregated schools, low expectations for racial minorities, and in general, a profile of low achievement for children from low-income families.

When I finally understood that education could mean a way forward out of those circumstances, I wanted to try to go to college. At age 21, I earned an adult high school diploma and conditional entrance into a university. Being a conditional student meant I had to make up coursework to prove I could make it academically at the college level. During that time, I worked two jobs, one washing dishes in the cafeteria at my residence hall, and the other at the law school, as a mock client for the grad students to practice client intakes with.

It was here that I gained an interest in the work of an attorney and decided to take classes to prepare me for law school. I was all set, until life stepped in and changed my plans. I was close to graduation when I was in a bad automobile accident. I had to quit my job and move off campus in order to focus on recovery. It was incredible that I was able to finish my senior year and graduate. In the process, however, I had to let preparing for the law school entrance exam fall to the wayside.

As I thought about what to do next, a good friend told me she never really saw me as a lawyer, but instead thought I’d make a great teacher. She handed me a green piece of paper with instructions on how to apply to a graduate program that would pay half of the cost for a master’s degree, train me to be a teacher, get me licensed, and guarantee a teaching job in Minneapolis Public Schools for at least five years. I consulted my family and friends, and to my surprise, everyone agreed that they had always felt education was a good fit for me.

I had never considered it, mainly because of my early struggles in school, but somehow, the universe took over and pointed me toward teaching. I was extremely lucky to be accepted to the Collaborative Urban Educator program at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, right out of college. The CUE program was an intensive year of teacher preparation that led to full licensure and my first job teaching fifth grade at an urban, art-infused public elementary school. In my third year of teaching, I became the first ever probationary teacher to reach Elementary Teacher of the Year finalist.

I found that I loved teaching; I excelled at it, and I was driven and inspired by working with children who were my age when I started to fall through the cracks of school. I was very focused on doing everything I could to prevent a single student of mine from experiencing school failure. My classroom became known for being a creative, fun, and rigorous environment where everyone could excel.

For myself, I developed a new sense about what it means to be a valuable contributor to something greater than myself. There is no satisfaction for me like that which comes from a hardworking parent who is grateful to you for guiding their child to success in school after ongoing struggles with learning, achievement, and social relationships.

Q. You have extensive experience in educating students with learning differences. What influenced you to go in that direction? Also, please tell us about the nonprofit organization you founded, Top of the Spectrum.

A: Harkening back to my first teaching job at the arts school, we had a regional classroom at our school for students with the most severe behaviors in the district. I would walk by that classroom and try to peek in. I would wonder about the students and the teachers, whom I rarely saw and who seemed to be a bit separate from everything else. That separation bothered me in many ways.

So, I began to befriend the teacher and the aides in the classroom. I started asking questions to learn more, and we became friends. One day, the teacher of that classroom asked me if would consider having one of her students come to my class for reading instruction. I was thrilled and gave an emphatic yes. I was so excited to see if I could work successfully with a child who was labeled with the most intensive of special needs. I’ll never forget that young man and our time together with him in my classroom. He became a model student in reading and was able to mentor younger readers. His success was hard earned, and his reputation changed, and he felt a part of our class.

The power of inclusion and belonging is incredible in terms of it being a catalyst for community and achievement. Everyone benefited from him being in our class. So, I became drawn to the idea of inclusion and its impact on learning. I also wanted to learn as much as I could about the root cause of learning differences and behavioral challenges. I went back to school and gained a second master’s degree this in Special Education. I then earned teacher certified in K-12 Learning and Behavioral Disabilities and began teaching as a special education teacher.

Shifting gears, On Top of the Spectrum is a non-profit organization in Tampa with the mission of expanding inclusive opportunities for young people. At age 3 my son was labeled with autism and other developmental differences. My life with him and the son that I later adopted who has Down Syndrome, as well as my school experience, has inspired me to work to create more inclusive communities.

I found as a parent that it was no simple task to do what comes simply to many others, like enrolling my kid in a karate class. Most of the time, the instructors are not knowledgeable on how to adapt to include kids who don’t respond to a single method of teaching. That means having to leave our community to search for any place that is accepting and prepared to engage a child who simply wants to be included and have fun learning for example, karate. Many times, those places do not exist, and it’s difficult to explain that to a child. So, we set about to change that and help prepare people to welcome anyone who comes through their doors as an opportunity to build stronger communities.

We created On Top of the Spectrum to focus on health and fitness because as children with special needs leave the school system as young adults, there is very little opportunity for them to be included in activities that nurture lifelong health and fitness. We work with gyms and personal trainers to enable them to train a wider range of people effectively, including people with autism. We also strive to increase access to outdoor adventures that have a physical element for people with developmental differences. In 2023 we are taking a diverse, inclusive group of young people to Tanzania to climb Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest free-standing mountain in the world. Some of our participants have been training for the past two years to be able to accomplish such an incredible personal challenge, all the while improving their personal health and fitness, inspiring the gyms they train at, and being fully included in the communities they train within.

Q. Tell me about your first experience teaching. How did it influence your career later? After years working in district schools, what influenced your decision to go out on your own?

A. My first teaching experience was in a unique public school in the heart of Minneapolis. Our students spoke 35 different languages and most lived at or below the poverty line. The school was art infused, meaning our students had access to curriculum and activities that were arts focused. For instance, I spent a few years working in collaboration with a professional dancer to create math curriculum that was taught through dance. This was important for our students because we faced a very real language barrier when trying to teach mathematics in English to students who did not speak English.

I was very fortunate to have had a wonderful principal in my first years of teaching that invited us as professionals to experiment to find what really worked in terms of individual student progress. I believe I had the very best possible start to my teaching career that I could have had. As I gained teaching experience and shifted from general education to special education, I expanded my teaching certifications to include more age ranges and subject matter, taught from kindergarten to high school, taught in a charter school, served as an assistant principal, and then went on the to the state department of education in a technical assistance role.

After that, I became an executive director of curriculum and instruction pre-K through 12 in a district serving about 25,000 students and families. Throughout my career, my focus remained singular in terms of my philosophy that innovative, inclusive education is the driver of the type of change in our world that I want to see. I want to see a world in which we don’t have to orchestrate inclusion, because it occurs naturally. This is important because the development of intellect depends on feeling and being safe to take academic risks within a supportive learning community.

In going out on my own to create something new, there are many reasons that I felt like I could not get change I wanted to see in education to occur on a large scale. I am a product and champion of public education, not so much as it is, but as it has the potential to be. As a parent of school aged children, I struggled with the lack of a meaningful education my children experienced in public school.

There was one event that triggered me to create the private school I had always thought about over my career. It came one day when my son came home and said to me, “Mom, I’m a weird kid.” That broke me, and for a time, it broke him too. He no longer wanted to go to school. I could no longer escape that this is not what should be happening in schools for children, and that we simply cannot keep doing things in ways that result in any child feeling like they don’t have a safe place of belonging in which to grow academically and socially. There were other issues that tipped the scale for me too, like the persistent achievement gaps in schools between differing racial and socioeconomic groups of kids, the loss of excellent teachers due to systemic wrongs, and archaic, sedentary systems of instruction.

Q. Congratulations on receiving support from the Drexel Fund. How did you learn about the organization and how is it helping you embark on this new adventure?

A. I am still in awe that I was one of just three chosen from among more than 250 applicants to become a Drexel School fellow this year. I learned about the Drexel Fund by googling, “grants for private school start up.” I came across them in 2019 and attended an informational meeting that was held at Step Up for Students. After I attended that meeting, Drexel reached out to me and let me know they had an interest in helping me launch my school.

So, while completing my Ph.D. at the University of South Florida, I started taking some early steps to prepare myself to be a competitive candidate. I worked on establishing the non-profit for the school, getting some professional development in the brain and learning, visiting other models, and having conversations about school start up with experienced people. For me, the fellows program allows me to work full-time on launching Smart Moves Academy.

Drexel helps seed private schools like mine by providing individualized resources to help fellows launch successful schools. As a fellow I get access to other school entrepreneurs that have been running high performing and successful private schools, executive coaching, and workshops to help me prepare a sustainable business plan. It’s wonderful to be surrounded by inspirational and visionary people who are doing the same work that I am.

Q. What type of research did you participate in at the University of South Florida and how it did help you develop this model?

A. At USF I focused my dissertation on research that would inform the model for Smart Moves Academy. My research involved more than 40 experts in brain development, learning, cognition and movement. The group was selected because of the members’ knowledge in the practical application of teaching strategies that embrace physical movement as a lever to optimize the brain in positive ways that impact learning. The results of my mixed methods study revealed a set of 27 elements that the experts felt should be present in an inclusive school where movement is a central part of how all students maximize their potential.

For me as a parent and as an educator, the most exciting of these strategies coming to life at Smart Moves Academy include daily neurodevelopmental movement, more rather than less recess, outdoor learning, and hands-on, active academics that align well with what we know about how the brain learns. When you combine these approaches inside of a well-designed and supported inclusive environment, you get our school.

Q. There are many schools that specialize in helping students on the autism spectrum. What will set Smart Moves Academy apart from the others?

A. Smart Moves Academy pairs engaging, rigorous academics with continuous development of the biological foundations critical to learning and social emotional well-being. We do this through movement. There is no other inclusive school in the United States that does this. For students that come to us with a label of autism, we can’t help but be very excited.

The research base of our neurodevelopmental approach is stunning when it comes to helping students with autism reach their potential and open doors to goals that may have been unreachable in the past. The inclusive model at Smart Moves Academy cannot be understated in terms of supporting a student with autism. Our school environment creates an authentic sense of belonging and safety for each student, thereby growing the self-confidence and perseverance needed for deep intellectual and character growth, as well as the formation of lasting friendships.

St. Patrick Catholic School in Jacksonville exemplifies the trend in the rise of Gardiner Scholarship students attending Florida Catholic schools, with an increase from one Gardiner student last year to seven this year.

Taylor Smoots is an energetic 4-year-old who loves to sing, dance and use his imagination. He’s so active that when it was time for him to enter preschool, three private schools questioned whether he would be successful in their voluntary pre-kindergarten programs.

It was already summer, and his parents were desperately seeking an educational environment that would help Taylor, who is on the autism spectrum, make the most of his unique abilities.

Then they discovered St. Patrick Catholic School in Jacksonville, a relatively small campus of 270 students from pre-kindergarten through eighth grade. They found the school welcoming, and the staff allowed a behavioral specialist to accompany Taylor and help him throughout the school day.

Taylor Smoots, a student at St. Patrick Catholic School in Jacksonville

Their decision to send their son to St. Patrick was solidified when they found out he qualified for a Gardiner Scholarship, which families can use to customize an educational program for their children with certain special needs including autism, Down syndrome and spina bifida. Approved expenses include tuition, therapy, curriculum, technology and a college savings account.

Half a year later, Taylor is thriving. His communication skills have improved. He’s made new friends and is excited to see his teacher every morning. And every afternoon, he tells his parents how much fun he had at school that day.

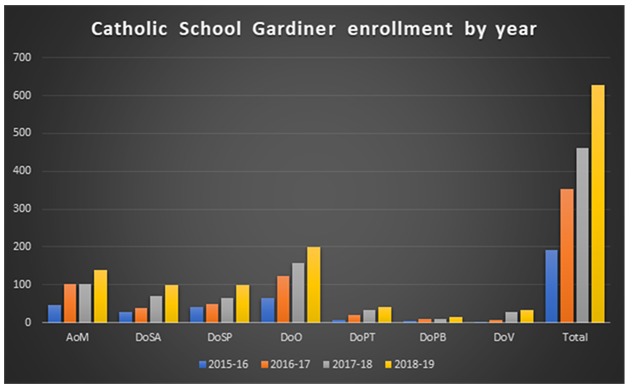

While Gardiner Scholarship enrollment is thriving statewide – the program currently serves more than 13,000 students and another 3,500 are on a wait list – it is experiencing notably rapid growth in Florida’s Catholic schools. According to figures provided by the Florida Conference of Catholic Bishops, the number of students attending Florida Catholic schools on Gardiner scholarships has increased 229 percent since the 2015-16 school year. That increase is consistent across the Archdiocese of Miami and the state’s six dioceses – St. Augustine, St. Petersburg, Orlando, Pensacola/Tallahassee, Palm Beach and Venice.

The Diocese of Venice realized the largest percentage increase in the past three years, growing from one Gardiner student three years ago to 33 students this year. The Diocese of Pensacola/Tallahassee had the second-highest percentage increase, growing from six Gardiner students to 40.

Meanwhile, the Diocese of Orlando, which grew from 65 Gardiner students to 201, boasts the largest Gardiner Scholarship enrollment.

The number of students attending Florida Catholic schools on Gardiner scholarships has increased 229 percent in the past three years. The Diocese of Venice experienced the largest percentage increase, while the Diocese of Orlando has the largest number of Gardiner Scholarship students.

Florida Catholic school officials cite a willingness to devote the type of individual attention Taylor is experiencing as one reason Catholic schools are seeing rapid enrollment growth among Gardiner families. They also theorize that the availability of Gardiner scholarships may be responsible for keeping Catholic school enrollment steady in Florida while other states are experiencing declines.

“Our schools provide a place where children are loved as part of a school family,” said Christopher Pastura, superintendent of Catholic Schools and Centers for the Diocese of St. Petersburg, which serves nearly 13,000 students. “I believe that it’s the Catholic emphasis on educating the whole child that attracts our Gardiner families.”

David Kimbell, parish manager and director of Catholic Immersion for Sacred Heart Cathedral Parish and School in Pensacola, agrees that Gardiner scholarships have made it possible for more children with unique abilities to reap the benefits of a Catholic school education.

“The scholarships allow a student with special needs to bring with them the funding necessary to ensure they have access to a great education,” said Kimbell, who will begin serving this fall as administrator for brand-new Morning Star Catholic High School in Pensacola. His school joins five other freestanding Morning Star schools across the state that cater to children with special needs. Several other Catholic schools have education for students with special needs embedded in their overall programs.

Morning Star schools first opened in the late 1950s when then-Archbishop Joseph P. Hurley of St. Augustine asked the Sisters of St. Joseph to launch schools for children with special needs. While Morning Star schools are a great fit for many parents of students with special needs, they’re not the only Catholic schools with the resources to help children with unique abilities. Many others, including St. Patrick, strive to accommodate individual needs, including rare conditions such as osteogenesis imperfecta, known as brittle bone disease, and phenylketonuria, which causes an amino acid to build up in the body and can lead to brain damage.

“We look at the children as having unique abilities,” said Jeffrey Kent, principal at St. Patrick. “We feel if we can give children opportunities, these kids can be the best versions of themselves.”

Exemplifying the growing enrollment trend of Gardiner Scholarship students in Catholic schools, St. Patrick had one Gardiner student last year; this year it has seven. Kent said the school expects Gardiner enrollment to be in the double digits next year.

Taylor Smoot will be among those students.

“We appreciate all the support St. Patrick has given our family,” his father said, “opening their doors when everyone else shut them.”

Lauren May, Manager of Catholic School Initiatives for Step Up For Students, contributed to this story.

Editor’s note: redefinED is supporting National Autism Awareness Month each Saturday in April by reposting articles from our archives that celebrate those who champion the educational rights of children with autism. Today’s post, which originally appeared in June 2018, features a dedicated teacher who refused to give up on a child with profound autism.

By Livi Stanford

Abigail Maass never spoke. It was hard for her to connect with others. She grew impatient easily.

Her struggles mirrored those of children everywhere who grow up with profound autism.

This all changed when she met Trina Middleton, a teacher with Duval County Public Schools.

Middleton said she consistently encouraged Abigail and gave her many opportunities to do different activities. She also enrolled her in intensive Applied Behavioral Analysis therapy. ABA is a therapeutic approach that helps people with autism improve their communication, social and academic skills.

“It is just believing in her abilities and supporting her and celebrating with her,” she said.

Priscilla Maass, Abigail’s mother, said Middleton’s belief in her daughter made all the difference.

“She is patient but is firm and the kids react to that,” she said. “She can think outside the box. She can come up with different techniques.”

According to Maass, Abigail has grown substantially in the 10 years that she has worked with Middleton, who now serves as the education director of the Jacksonville School for Autism.

According to Maass, Abigail has grown substantially in the 10 years that she has worked with Middleton, who now serves as the education director of the Jacksonville School for Autism.

Now, Abigail, 12, can use some sign language to communicate, especially about her feelings. She uses her iPad more frequently as a communication device. She finds productive activities at her school, such as helping in the lunchroom. She is also now able to feed herself.

Maass said that in Middleton, Abigail has found an educator she trusts.

“She gets her out of her shell,” she said. “She does not get offended when Abigail will tell her to go. When she needs someone to rely on, Abigail tends to go toward Trina.”

Parents and administrators describe Middleton as dedicating her life to children with special needs. At the Jacksonville School for Autism, Middleton has been credited with expanding classroom programs and for developing a bridge program with the goal of helping transition students from JSA into typical learning environments.

“She is the voice of calm in the storm of Autism for our families and staff, and her presence simply makes everyone in our school program more confident in their capabilities,” said Michelle Dunham, JSA’s executive director. “A true testament to her strength as a leader can be seen in the relationships she maintains today with so many teachers she worked within both public school and JSA.”

Middleton began her career in 1993, teaching emotionally disturbed children in St. Johns County.

She took some time away from teaching to raise her own children. In 2003, she began teaching at Duval County Schools. After four years, she became a site coach for schools that have self-contained classes for students with autism.

That lasted until 2012, when massive budget cuts were made to the school budget.

Middleton said she could not look her parents in the eyes and tell them their children were getting all they needed. She felt the budget cuts fell disproportionately on special needs programs.

The cuts, implemented in 2011, affected classroom curriculum and supplies as well as direct services in speech/language and occupational therapies. They also affected training for staff who worked with children with autism in the classroom.

Student-to-teacher ratios rose, sometimes 5 to 1 in self-contained classrooms, Middleton said.

And she had other ideas about how to change education for students with special needs. She wanted more instructional flexibility than the public school allowed.

“Students’ self-regulation and communication needs to be the focus prior to the focus being on academic areas,” Middleton said.

After learning of the budget cuts, Middleton decided to change course. She took a job at the Jacksonville School of Autism, a nonprofit K-12 educational center for children ages 2-22 with Autism Spectrum Disorder — a neurological condition characterized by a wide range of symptoms that often include challenges with social skills, repetitive behavior, speech and communication.

Founded by Dunham and her husband, the school continues to thrive with 51 students and 50 therapists and classroom teachers. The school also implemented a vocational training program for older students to help them acquire skills to become gainfully employed.

Serving as educational director, Middleton said she is most proud of her ability to establish a strong collaborative relationship between the school’s classroom and clinical staff, tailoring instruction to overcome each student’s individual challenges.

She frequently brings the entire clinical and classroom teams together to discuss students’ needs and progress.

Asked what is the most important thing that educators must do when they teach those with autism, Middleton said it is essential to respect them as human beings with intellectual capacities that far exceed their ability to communicate.

Students like Abigail Maas can attest.

Editor’s note: redefinED is supporting National Autism Awareness Month each Saturday in April by reposting articles from our archives that celebrate those who champion the educational rights of children with autism. Today’s post, which originally appeared in November 2015, relates the story of a South Florida mom who refused to give up until she found the right school for her daughter.

by Travis Pillow

When Charleen Decort was looking for the right school for her daughter, she traveled around South Florida, looking at factors some parents rarely consider, like the color of the walls and the shade of the lights.

When she found her current school, a predecessor of what is now Connections Education Center of the Palm Beaches, another factor carried the day: Trust.

"She has to feel comfortable around you," Decort said of her daughter, who has autism, "and they take the time to do that here. That's big."

She got on the waiting list for the school's early learning program. If a spot hadn't opened in time for kindergarten, Decort said she would have considered teaching her daughter at home, or even moving somewhere else.

Fortunately, she found a place for her daughter, now in third grade, in a growing array of small schools, some public, some private, that are purpose-built to serve children who might be distracted by the flickering of a fluorescent bulb, or rely on an iPad to communicate, or have other special needs that can be hard to accommodate in traditional schools.

Connections — currently a private school, with a charter application set to be approved later today by the Palm Beach County School Board — is a newcomer to this sector-agnostic niche, which caters to children with autism.

Debra Johnson helped start Connections this year, after the Renaissance Learning Center, where she had been principal, moved north to Jupiter. It's now housed in a world-class facility at the Els Center for Autism, as first reported by the Palm Beach Post. Johnson and several other employees launched the new school in West Palm Beach to accommodate parents who couldn't make the drive to the north end of the county.

Other schools have sprung up in surrounding communities, with different emphases but similar goals. There's the Palm Beach School for Autism, a charter school in Lantana. Mountaineers School of Autism is a K-12 private school in West Palm Beach. Oakstone Academy promotes inclusion for special needs students.

Johnson said there's enough demand to support diverse options. Schools like hers can serve a limited number of students, and want to keep student-to-staff ratios low. Connections currently serves slightly more than 20 students, with a student-to-staff ratio of about two-to-one. Its charter application suggests it could eventually grow to 85 students in grades K-8.

"We want to stay small," Johnson said. "We picked the name Connections Education Center because that's our mission — to be connected with the parents and the community."

One recent morning, older students were communicating with teachers using a TouchChat iPad app. Across the hall, other students worked on art therapy, building models of their hands with clay.

In an adjacent room, some of the school's youngest students listened to the "Wheels on the Bus." One child focused his gaze on the pages of an accompanying book. One sat still, bristling at the loud noise. One cracked a smile and started dancing to the music.

Three children, sitting just a few feet from each other, were having completely different reactions. That, Johnson said, is why individual attention can make a difference.

"If you've met one person with autism, you've met one person with autism," she said.

The school can afford to hire extra staff thanks in part to its benefactors. Johnson said Connections started with financial support from a "very generous angel" who has a family member with autism but wants to remain anonymous. Its narrow focus also helps it apply for grants. According to its charter application, the school "has the backing of two family foundations and other community partners to assist in bridging the gap between public and private funding."

Decort, who also serves as the school's parent liaison, said the result is a school that is "more family-like," that can "tailor (instruction) to what your child needs," and that helps children prepare to live independently. It takes students on shopping trips and out to restaurants, to help teach life skills they'll need as adults.

"She doesn't need a babysitter," she said of her daughter. "She needs someone who will challenge her."

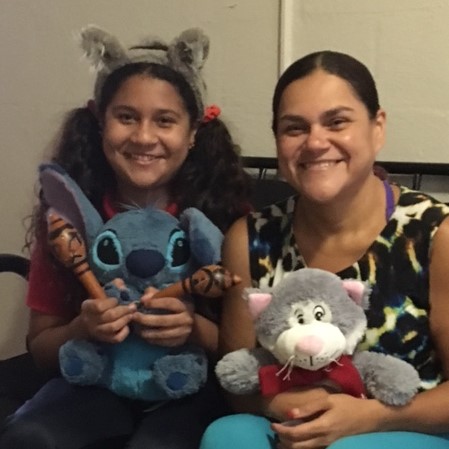

Aleena Martinez and her mother, Damaris Lorenzo, pose with Aleena’s beloved stuffed animals. Aleena is one of nearly 1,900 Florida students on a wait list for the Gardiner Scholarship for children and young adults with certain special needs. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis recently vowed to end the wait list for 2019-20.

TAMPA – Aleena Martinez bounded into her family’s small, sparsely furnished living room as if it were an inflatable bounce house. A pair of blue rabbit ears crowned her dark curls and a menagerie of stuffed animals filled her arms.

The 12-year-old abandoned the animals on the couch and ran to the kitchen, where she began rummaging in the cabinets. She returned waving two boxes of cake mix – one vanilla, one brownie.

“We’ll bake one, then we’ll put them together,” Aleena told her mother, Damaris Lorenzo. “It’s science!” she announced with enthusiasm.

Aleena had just arrived home from her neighborhood school in east Tampa, a bundle of energy. She doesn’t dislike the school, but she’s finding it much different from the one she attended in her native Puerto Rico. Aleena, who is on the autism spectrum, is more comfortable in a smaller school setting. Distractions can trigger her post-traumatic stress disorder, a result of her family’s harrowing exodus to Florida in the wake of Hurricane Maria.

Her mother would have preferred to send Aleena to private school but cannot afford the tuition. The fifth-grader, along with nearly 1,900 other Florida children, has landed on a wait list for a Gardiner Scholarship for students with special needs in the wake of a demand that has outpaced state funding.

Damaris received encouraging news last week when Gov. Ron DeSantis pledged to eliminate the wait list for the 2019-20 school year. In speaking engagements in Jacksonville and Orlando, DeSantis said he has allocated enough money in the 2019 state budget to provide relief to families eager to find the most appropriate educational environment for their children.

Administered by the nonprofit Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog, the scholarship serves nearly 12,000 special needs students. Families can use the funds to pay for a variety of educational services, including private school tuition, tutoring and therapies, in addition to contributions to the Florida Prepaid College Program. The scholarship has enjoyed broad bipartisan support since its inception in 2014 and was expanded in 2015 to include students like Aleena who are on the autism spectrum. Those students now account for 66 percent of scholarship recipients.

Damaris learned about the scholarship when she saw it advertised on benches near her neighborhood.

She began envisioning using the money, which this school year averages $10,400, to pay for private school tuition and speech, occupational and group therapies for Aleena.

“I know of a private school here where she would be better off,” Damaris said. “It’s a smaller setting with one-on-one (instruction), and all the students get iPad tablets and there’s music and arts. I know she would like it there.”

Damaris didn’t leave Puerto Rico with Aleena and Aleena’s older brother voluntarily. Five days before Hurricane Maria devastated the island, she underwent a complicated abdominal surgery. When the island became flooded and lost power, Damaris scrambled to find hospital care. Her surgical wounds became infected, and without access to a doctor or antibiotics, her condition rapidly deteriorated.

“I caught sepsis in my whole body,” she said.

Damaris eventually found a doctor who approved her departure from the island, but travel out of Puerto Rico was limited. She had to leave her extended family behind.

After arriving in Tampa, Damaris spent a couple of months in a hospital while the family adjusted to its new home. None of it was easy.

“Aleena doesn’t really like a lot of change,” Damaris said, adding that post-hurricane, her daughter began experiencing hallucinations triggered by post-traumatic stress disorder. The girl is undergoing evaluation for bi-polar disorder and schizophrenia.

Despite Aleena’s challenges, Damaris is happy her daughter has made progress – and friends – at the neighborhood school. But she is convinced the private school will be a much better fit.

Meanwhile, Aleena who has disappeared into another room, suddenly reappears in the living room singing and “flossing,” doing the popular side-to-side dance move inspired by the online video game “Fortnite.”

She interrupts her recitation of things she loves, including painting and riding her purple Schwinn bicycle, with a panicked cry.

“The solar-system project! I left it at the therapist,” she says. “I need it; it’s a project. I don’t have any more paint.”

Damaris assures her they can return to the therapist’s office to retrieve the project, but the trip will have to wait. The weary mother, still recovering from a medical procedure she endured the previous day, sighs with a grin.

“It’s like this all the time,” she says.

A Gardiner Scholarship would provide some much-needed help.

Editor's Note: This is the third in a week-long series of posts from students and parents who've benefited from school choice. For yesterday's story, click HERE.

by Ana Garcia

We had become parents a second time. This time it was a boy. Kevin was a vivacious, wonderful baby full of laughter and joy. His development took the usual course. He was a bit behind in language, but we were told it was of no concern yet. A littler later, however, we noticed Kevin had repetitive behaviors, was lining his toys up and, well, had a very strong “personality.”

When we sought the assistance of a speech therapist, she referred us to Early Steps, an organization to screen autism.

We’ve turned over redefinED this Thanksgiving to the important voices in ed choice – parents and students.

The day we were told our son was autistic, my husband and I were shocked by the words, but at the same time we knew.

We immediately began therapies to help his speech and decided to place him in a public school program for pre-schoolers with autism.

At the time, we were completely satisfied with his progress. We found that he adapted well to the learning environment.

However, with our move, we had to change schools. Furthermore, once he exited the pre-kinder autistic class, where there were only five children and two instructors, he was assigned to an inclusion class with 25 students and only one instructor and a “floating” inclusion teacher.

Kevin was left soiled, was not fed for over a month, and continuously eloped to the parking lot.

We finally decided to place Kevin in an ABA center to help him with his behaviors, which were seriously impeding daily life.

Since the ABA was six hours a day, we decided to register him in homeschool. At first, this was very difficult, but when I learned the Gardiner Scholarship helped families like us, we were immediately alleviated.

The Gardiner Scholarship is an education savings accounts for students with special needs such as autism and Down syndrome. It has been a Godsend to our family. Not only do I have the ability to choose homeschool for my son, I have resources that I would not have been able to afford to give him otherwise.

The public sector is not a good fit for Kevin, who is now 9 years old, as his needs extend beyond what it can provide.

Now I have the tools and resources to provide my son with diverse curricula, private tutors, sensory and physical materials, and technological devices.

I attribute the great strides Kevin has made in his development to the Gardiner Scholarship. It enabled us to help him not only become verbal, but fluent.

I cannot imagine a world without Gardiner.

Ana Garcia is a mother in Homestead, Fla. The Gardiner Scholarship is administered by nonprofits such as Step Up for Students, which hosts this blog.

Coming tomorrow: The daughter of a single mother devotes her future to giving back, in hopes her story on the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship can inspire others.