It seems especially appropriate midway through National School Choice Week to ask:

It seems especially appropriate midway through National School Choice Week to ask:

Can the use of state “Blaine Amendments” to prohibit publicly available funds from being used by parents at religiously affiliated educational options be considered discriminatory? And if so, does that discrimination violate a family’s right guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution to equal protections under the law?

Those are questions education choice advocates have been asking for nearly two decades. The issue came to a head last week when the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue.

Voucher opponents have managed to avoid these questions since 2006 when the Florida Supreme Court ducked the state’s “Blaine Amendment” arguments altogether in Bush v. Holmes. Opponents lucked out again when they seized the opportunity to pour millions into the Douglas County, Colorado, school board races to kill a voucher program that would have been a perfect test case for the U.S. Supreme court in 2017.

Voucher opponents may get lucky once again in 2020. It’s possible the U.S. Supreme Court will sidestep the issue and instead scold the Montana Supreme Court for thinking tax credits are functionally the same as direct tax dollars – a distinction the court already made in Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn in 2011.

And while Espinoza is an important case, some commentators have overblown its possible impact. Ian Millhiser, writing for Vox, and Jay Michaelson, writing for the Daily Beast, incorrectly claim that a victory for school choice supporters would be a “mandate” for states to fund religious schools and “starve” public schools. David Dayen, executive editor for the American Prospect, elevates the case to conspiracy level “brought … to undermine public education” by corporations seeking to obtain tax breaks from their donations to religious schools.

There is no corporate conspiracy theory, nor will Espinoza result in the starvation of public education, dozens of new voucher programs, or even a mandate to fund private religious schools.

At best, the U.S. Supreme Court simply will provide some consistency, or at least some guidance, on how all the various state Blaine Amendments can or cannot be applied to education. Florida is a great example of how Blaine Amendments have been inconsistently applied.

In 2004, the First District Court of Appeal ruled the state’s first voucher program, the Opportunity Scholarship, unconstitutional because it violated the state’s constitutional ban on direct or indirect aid to religious institutions. But the ruling was unsatisfactory because it failed to address the dozens of examples raised by voucher supporters. Examples included several legal cases in which churches benefiting from state or local programs did not violate Blaine.

In Koerner v. Borck (1958), the Florida Supreme Court ruled that a portion of a last will and testament allowing for land donation to Orange County for use as a park as long as a local church be granted perpetual easement to access the lake was constitutional because the benefit to the church also was a benefit to the general public.

In Southside Estates Baptist Church v. Board of Trustees (1959), the Court ruled that the use of public schools to hold private religious meetings did not violate the “No Aid” clause.

In Johnson v. Presbyterian Homes of Synod of Florida (1970), the Court ruled that tax credits for retirement homes were constitutional even if the retirement home was owned and operated by a religious organization. The Court stated: "A state cannot pass a law to aid one religion or all religions, but state action to promote the general welfare of society, apart from any religious considerations, is valid, even though religious interests may be indirectly benefited."

In Nohrr v Brevard County Education Facilities Authority (1971), the Court ruled that the government could issue bonds for facilities at religiously affiliated schools.

And in City of Boca Raton v. Gidman (1983), a case that dealt with publicly funded daycare at a religiously affiliated program, the Court stated: "The beneficiaries of the city's contribution are the disadvantaged children. Any “benefit” received by the charitable organization itself is insignificant and cannot support a reasonable argument that this is the quality or quantity of benefit intended to be proscribed."

These cases strongly suggest that programs created to benefit the general public CAN be provided by religious organizations, and that any benefit derived from the program to the church is merely incidental.

Florida’s Opportunity Scholarship Program voucher also forbade private schools from admitting students based on their religion and prohibited private schools from requiring students to take religious courses or attend religious services. The scholarships themselves didn’t cover the full cost of tuition, though the private schools had to accept the voucher as full payment. In other words, the private schools educated each child at a loss compared to private pay students. Voucher supporters argued that all these facts made education at a private religiously affiliated school functionally no different, as far as the “No Aid” clause was concerned, than medical services provided at a religiously affiliated hospital.

And so another question comes to mind: Why is it possible for individuals to use public programs to pay for medical services at religious hospitals, but not use public funds to pay for education at religious affiliated schools? The First District Court of Appeal failed to address this example entirely.

Voucher supporters pointed to the McKay Scholarships for children with disabilities along with the Florida Private Student Assistance Grant Program and Bright Futures Scholarships, which could be used at one of 23 private religiously affiliated colleges in Florida. The state Attorney General noted that the Legislature appropriated nearly $9 million to private religious universities in Florida in 2002.

Other examples include rent paid to churches for use as polling places, subsidized childcare and prekindergarten education at churches and religious schools as well as public funds to churches for the preservation of historic structures. The First District Court of Appeal ignored these examples, too.

The First District Court of Appeal defined the “No Aid” clause as prohibiting any funds being taken directly from the treasury to be paid to a religious organization, regardless of how the money arrived, even indirectly through choices made by parents offered scholarships. This ruling threatened many existing programs in Florida highlighted by the lawyers for the state.

Even Judge James R. “Jim” Wolf, who wrote a concurring opinion, argued the ruling endangered other programs unless arbitrarily confined to K-12 education, stating: "In order to avoid catastrophic and absurd results which would occur if this inflexible approach was applied to areas other than public schools, the majority is forced to argue that the opinion is limited to public school funding and article 1, section 3 may not apply to other areas receiving public funding."

In other words, the court had to distinguish K-12 education as being uniquely prohibited by the “No Aid” clause compared with other aid programs. Florida is not unique when it comes to Blaine. Other states have treated K-12 education as being distinct from other government programs in which churches may participate or benefit.

What conclusion can we draw from all of this?

Don’t expect Espinoza to be a major game changer. State legislatures still must create voucher programs and families still must choose schools for their children. All we can hope for is that the U.S. Supreme Court will provide some clarity in how Blaine Amendments can or cannot be applied.

Hopefully, we’ll learn that distinguishing K-12 education from other publicly beneficial programs is arbitrary and in error.

Florida's First District Court of Appeal

This is the second of two posts on the judicial history of Florida's Blaine Amendment with regard to public aid to private religious institutions. Part one can be read here. The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to weigh in on the constitutionality of state Blaine Amendments in 2020.

Lawyers defending Florida’s first school voucher program in Bush v. Holmes demonstrated the state historically allowed public funding to flow to many religious organizations providing public services, including through the McKay Scholarship for children with special needs. The First District Court of Appeal refused to acknowledge these programs.

Supporters of the Opportunity Scholarship program also cited several Florida Supreme Court cases which upheld aid to religious institutions as constitutional. But the appellate court found a way to ignore this precedent too.

Koerner v. Borck (1958) dealt with the last will and testament of Mrs. Lina Downey, who had donated a parcel of land to Orange County for use as a county park, but with the provision that Downey Memorial Church be granted a perpetual easement to access the lake for the privilege of baptizing members and swimming.

The court upheld the will, concluding,

“to hold that the Amendment is an absolute prohibition against such use of public waters would, in effect, prohibit many religious groups from carrying out the tenets of their faith; and, as stated in Everson v. Board of Education, supra, 67 S. Ct. 504, 505, "State power is no more to be used so as to handicap religions, than it is to favor them."

In 1959 the Florida Supreme Court heard Southside Estates Baptist Church v Board of Trustees, a case in which the court ruled religious institutions could use public buildings (in this case a public school) for religious meetings.

The court was not persuaded that minimal costs associated with the “wear and tear” of the building constituted aid from the public treasury, and concluded there was “no evidence here that one sect or denomination is being given a preference over any other.”

In Johnson v. Presbyterian Homes of Synod of Florida, Inc. (1970), tax collectors for Bradenton and Manatee County challenged a law that gave property tax exemptions to non-profits operating homes for the elderly after a religious organization applied. Presbyterian Homes of Synod, a religious non-profit operating homes for the elderly, maintained a religious atmosphere, offered religious services and employed an ordained Presbyterian minister who conducted services every day except Sunday. Most residents were even practicing Presbyterians.

The Florida Supreme Court determined the tax exemption benefit was available to all, not just Presbyterians, and ruled:

“A state cannot pass a law to aid one religion or all religions, but state action to promote the general welfare of society, apart from any religious considerations, is valid, even though religious interests may be indirectly benefited.”

Nohrr v. Brevard County Education Facilities Authority (1971) dealt with the issue of government issue bonds potentially being received by religious schools. The Florida Supreme Court found no problem here either.

In all four cases the Florida Supreme Court held the law did not violate the constitutional prohibition on direct or indirect aid to religious institutions. In all instances, the court examined who benefited from the aid, and required that the aid benefit the general public and/or required that no religious group be favored over the other.

The appellate court majority brushed aside these arguments, noting that the Opportunity Scholarship was different because the financial aid came directly from the state treasury, making the scholarship “distinguishable from the type of state aid found constitutional.” In fact, it appears the appellate court restricted Florida’s “no aid” provision to “payment of public monies,” though it failed to consider other similar programs such as McKay.

Having crafted itself exemptions to prior state Supreme Court precedent, the appellate court cited cases in Washington (2002), South Carolina (1971) and Virginia (1955) where state supreme courts held that direct subsidies to students were, in effect, benefits to religious schools.

This directly contradicted the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), which determined the benefit to religious institutions from school vouchers were merely “incidental.”

The Florida Supreme Court had even weighed in on whether these benefits were direct or incidental during a 1983 case, City of Boca Raton v. Gilden, which upheld the city’s subsidy to a religiously affiliated daycare provider. The court declared:

“The beneficiaries of the city's contribution are the disadvantaged children. Any ’benefit‘ received by the charitable organization itself is insignificant and cannot support a reasonable argument that this is the quality or quantity of benefit intended to be proscribed.”

The appellate court in Bush v. Holmes failed to understand that the constitutional question hinged not on the method of aid, but who was the intended beneficiary of the aid. Though Florida’s constitutional language may appear clear, its longstanding history of neutrality in funding medical and educational services at secular and religious institutions, has muddied the waters.

On June 7, 2005, opposing sides met for the final time to argue before the Florida Supreme Court over the constitutionality of the state’s first voucher program, the Opportunity Scholarship. Supporters of the program for low-income students had won several important victories, forcing opponents to abandon all but one remaining argument -- that the voucher violated Florida’s “Blaine Amendment.”

Florida’s Blaine Amendment, Article 1, Section 3 of Florida’s constitution, is one of the most restrictive in the country. It reads:

“No revenue of the state or any political subdivision or agency thereof shall ever be taken from the public treasury directly or indirectly in aid of any church, sect, or religious denomination or in aid of any sectarian institution.”

Just seven months earlier the First District Court of Appeal issued an “en banc” decision, with eight of the justices declaring the program violated Article 1, Section 3.*

A ruling by Florida’s Supreme Court on the matter could have sent the case to the U.S. Supreme Court to resolve, once and for all, how state Blaine Amendments could be applied to restrict or support state-funded scholarships to attend religious schools. But the Florida Supreme Court ducked the issue altogether. In a stunning move, the Court reversed course and resurrected two arguments it had rejected just four years before.

The U.S. Supreme court isn’t expected to resolve the lingering questions over state Blaine Amendments until 2020.

Florida’s First District Court of Appeal had the last word on the matter, but despite claiming a “clear meaning” and “unambiguous history” of Florida’s no aid clause, the court’s decision left gaping holes and many unanswered questions.

Lawyers defending the voucher program argued the scholarship did not violate the Florida Constitution because the benefit was to the student and the general public, and not intended to aid religious organization. In fact, the entire program was neutral with respect to religion because the vouchers were issued to parents who could use them at any private religious or non-religious school of their choosing.

Furthermore, the Opportunity Scholarship forbid private schools from selecting students on a religious basis and stated that scholarship students could not be compelled to pray, attend worship or even take religious courses.

Supporters noted several state programs benefiting Florida residents were provided at religious or religiously-affiliated institutions. Programs included Florida Bright Futures Scholarship, John McKay Scholarships, Florida Private Student Assistance Grant Program and eight other scholarship programs, along with the 23 private religious colleges accepting them. Supporters pointed to direct financial support for religiously-affiliated colleges, including $8.9 million in 2002 for libraries at Bethune-Cookman, Edward Waters College and Florida Memorial College.

Attorney General Robert Butterworth pointed to other direct appropriations, such a rent paid to churches used as polling places and subsidized pre-K at religious preschools.

Butterworth even noted that state funds provided subsidized medical care at religiously affiliated hospitals such as St. Mary’s in West Palm Beach or Baptist Medical Center in Jacksonville.

A direct taxpayer subsidy to a sick patient to attend any hospital, religious or non-religious, of their choosing, should not be treated any differently under the law that a scholarship to attend a religious or non-religious school, the Attorney General argued.

The appellate court majority responded to these arguments with deafening silence, with no mention of the McKay Scholarship, the state’s only other K-12 voucher program funded by direct appropriations at the time. The ruling was narrowly tailored to only one single K-12 scholarship program.

Even Judge Wolf, who concurred in part, criticized the majorities incoherent constitutional interpretation stating,

“In order to avoid catastrophic and absurd results which would occur if this inflexible approach was applied to areas other than public schools, the majority is forced to argue that the opinion is limited to public school funding and article 1, section 3 may not apply to other areas receiving public funding.”

The court would not only fail to grapple with these important constitutional questions, it would end up ignoring Florida’s own legal precedent on the matter.

Coming Thursday: Florida has a long history of court cases that upheld the constitutionality of providing aid to religious institutions.

*Seven justices ruled the OSP should be struck down entirely for violating the state’s “Blaine Amendment.” Just one justice ruled the OSP should be partially struck down by requiring religious schools to be excluded from the program. Five justices ruled the program should be upheld.

Like every traditional “private” school, charter schools are held to basic legislated standards of curriculum and safety with one major exception. For better or worse, the most serious governmental imposition on the charter school has been the exclusion of religion.

The teachers unions have discovered that charter schools are enemies of the good society.

Bernie Sanders is with them, warning us that these institutions are anti-democratic and must be brought to heel – that is, in reality, to the heel of the union, which insists that charter schools are essentially private and threatening to work evil among the poor in our cities.

And private they are in varying degrees depending to some extent upon the terms of their particular compact. The point of the original charter concept (1971) was to aid the liberation of the low-income parent and child from subordination to those unchosen strangers from government and union who control the self-styled “public” school located in their compulsory attendance zone.

Charter schools were to give the poor a taste of the personal and civic responsibility enjoyed by wealthier Americans who can and do freely cluster in chosen government schools in the suburbs or pay tuition in the private sector.

Like every traditional “private” school, the charter is held to basic legislated standards of curriculum and safety with one major exception. For better or worse, the most serious governmental imposition on the charter school has been the exclusion of religion.

Though the parental choice among charter schools is completely free, the schools themselves are unfree either to recognize or reject God. They must secure their students’ ears, eyes and thoughts from any suggestion of the divine, either positive or negative, with all the predictable effects of this upon the child’s mind.

In many states, this censorship is defended as a requirement of 19th century “Blaine Amendments” to the state constitution forbidding public aid to religion. The non-Blaine charter states have accepted this intellectual taboo as the norm and as the diktat of the union.

Given relevant precedent and the seeming attitudes of a majority of the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, there seems no barrier under the federal constitution to the extension of the state’s authority to subsidize its parents’ choice of religious charter schools. The larger question will be whether the states are forbidden by our national law to actually exclude aid to the subsidized choice of such schools by parents. Next term, the Court will consider Espinoza vs. Montana Dept. of Revenue, presenting this very issue.

If we have vouchers, must they be for the choice of all legitimate schools? Here the school and parent may one day have reason to thank the teachers union for its clear insight that the charter school is indeed private.

Montana parents are appealing a ruling that found tax credit scholarships unconstitutional - and its impact might be felt around the entire country

Montana parents appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court last week, asking the court to overturn a ruling that found tax-credit scholarships unconstitutional in the state.

The Montana Supreme Court had ruled 5-2 in December that the state’s tax credit scholarship program violated the state’s constitutional bans aid to sectarian schools. The ruling allowed the state to create a new tax credit scholarship program for students to attend only non-religious private schools.

“It is a bedrock constitutional principle that the government cannot discriminate against religion,” said Institute for Justice attorney Erica Smith in a press release. “Yet for the past 24 years, some states have blocked religious schools and the families who choose them from participating in student-aid programs. It is time for the U.S. Supreme Court to step in and settle this issue once and for all.”

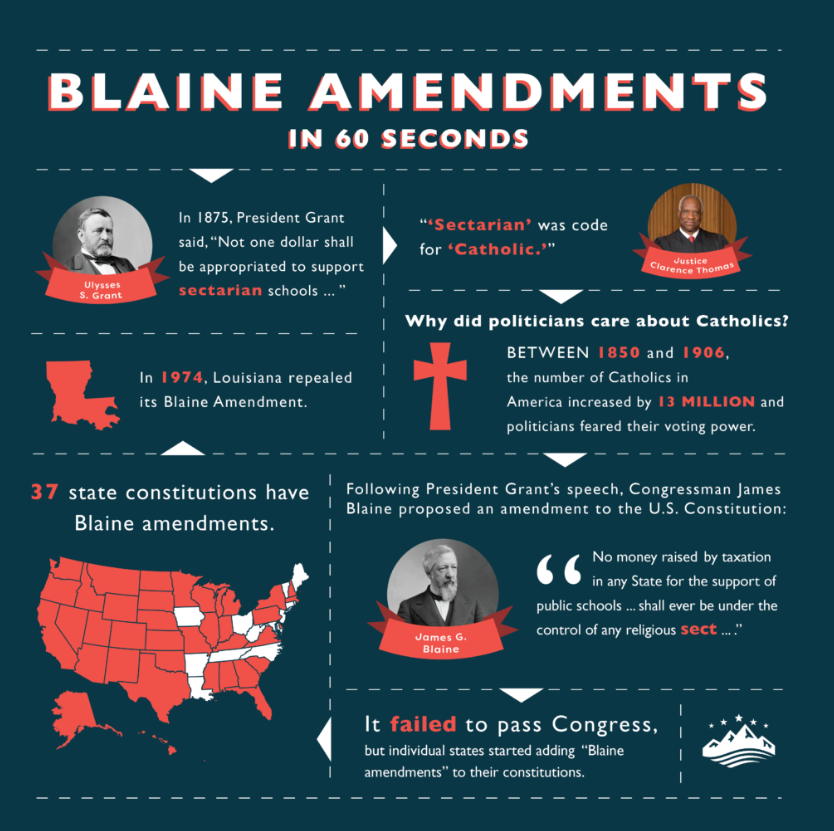

At issue is Montana’s Blaine Amendment, a relic of anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant bias that swept America in the late 19th century. The amendment is still on the books and bans direct and indirect aid to religious schools.

Florida has a similar ban on aid to religious institutions, though these arguments failed to sway the Florida Supreme Court in Bush v. Holmes (2006) and McCall v. Scott (2017).

Scholarship parents in Montana are asking the U.S. Supreme Court to determine if banning participation in educational programs because of religious preferences ultimately discriminates against religious parents in violation of the “free exercise” clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Past U.S. Supreme Court cases also come into play, such as Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, which ruled vouchers did not violate the Establishment Clause because aid was to the student and not the religious institution.

The Court also has rejected the notion that tax credits are equivalent to tax expenditures by the government in Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn (2011).

More recently, the Supreme Court ruled in Trinity Lutheran v. Comer (2017) that state governments could not deny grants to religious organizations for playground resurfacing while providing grants to similar, but non-religious organizations. Denial of the grant, the court ruled, violated the “free exercise” clause of the First Amendment.

In light of that ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the Colorado Supreme Court to revisit Taxpayers for Public Education v. Douglas County School District (2015), which found the district-run voucher program violated the state’s Blaine Amendment ban on direct aid to religious schools. However, the voucher program was dismantled and the issue rendered moot after the American Federation of Teachers funneled $600,000 into local school board election and took over conservative Douglas County.

Blaine Amendments have successfully struck down vouchers in Arizona and Montana but failed in Florida, Nevada and Oklahoma.

If the appeal from the Montana parents is accepted, a ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court likely would clarify how states may read their respective Blaine Amendments.

Montana's Supreme Court decision striking down the state's tax credit scholarship sets up a showdown in Washington over Blaine Amendments.

By Andrew Wimer

Last week, the Montana Supreme Court struck down the tax credit scholarship program created by that state’s legislature in 2015. The decision ignored recent U.S. Supreme Court precedent and was out of line with every other state court decision involving tax credit scholarship programs. The Montana program provides a modest tax credit (up to $150 annually) to individuals and businesses that donate to private scholarship organizations.

There are 18 such programs nationwide, or there were until last week. The Montana Supreme Court struck down the program because it allowed children to attend both religious and non-religious schools. The decision was grounded in Montana’s Blaine Amendment.

Many in the educational choice community are aware of Blaine Amendments, but if you’re not, here’s a quick primer. In the 19th Century, anti-Catholic animus led to a movement to pass a U.S. Constitutional Amendment that would ban public funds for “sectarian” — code for Catholic — schools. The federal effort failed, but numerous states passed similar amendments modeled after Maine Sen. James G. Blaine’s proposal.

The U.S. Supreme Court has been edging toward declaring Blaine Amendments unconstitutional, coming close in 2017’s Trinity Lutheran decision. This decision declared that Missouri could not use its Blaine Amendment to deny funds to a Lutheran pre-school that had applied for playground resurfacing money. Chief Justice John Roberts used strong language in his majority decision, saying that, “the exclusion of Trinity Lutheran from a public benefit for which it is otherwise qualified, solely because it is a church, is odious to our Constitution … and cannot stand.”

Every other state high court to consider the constitutionality of a tax credit scholarship program, dating back to 1999, has ruled in favor of educational choice. While the Montana ruling doesn’t threaten programs in other states, it takes away scholarship money from many needy and deserving children in Big Sky Country. Eliminating the program harms children who were attending eligible private schools.

The Montana decision is bad news for families relying on the scholarship program. But good news could be on the way.

This decision invites U.S. Supreme Court scrutiny because the Montana Supreme Court explicitly refused to consider whether that state’s Blaine Amendment squares with the U.S. Constitution, which demands that government remain neutral on matters of religion (and which has previously upheld publicly funded educational choice programs that include religious options). The Institute for Justice, which represents Montana parents in the case, will appeal the ruling and we expect strong support for our petition. Indeed, the Court appeared poised to consider a nearly identical issue, immediately after it decided Trinity Lutheran, when it vacated a Colorado Supreme Court decision striking down a publicly funded scholarship program. However, that program was legislatively repealed, and that case mooted.

There is also a possibility for a stay of the decision, which could allow families to continue accessing scholarships while the U.S. Supreme Court considers hearing the case. Otherwise, many children could be forced to switch schools starting next year. Stay tuned.

Andrew Wimer is the Assistant Communications Director for the Institute for Justice.

Shortly after Montana created its first tax credit scholarship, Mike Kadas, head of the state's Department of Revenue, unilaterally declared that scholarships could not be used at religious private schools. Kadas argued the state's Blaine Amendment, a 19th century relic of Catholic discrimination, barred "direct or indirect" appropriations to religious organizations.

School choice moms struck back with a lawsuit claiming religious discrimination.

“The rule also violates both the state and federal Constitutions because it allows scholarship recipients to attend any private school except religious ones,” Erica Smith, an attorney with the institute, said in a press release at the time. “That’s discrimination against religion.”

Now two years later these moms will have a chance to make their case before the Montana Supreme Court today.

The case may have national implications. To date, cases hinged on whether the use of school voucher programs violated so-called "separation of church and state" requirements in the U.S. and state constitutions. Sixteen years ago the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris that vouchers did not violate the U.S. Constitution. Several other state supreme courts have ruled the same.

While choosing a religious school with vouchers, or tax credit scholarships, is constitutional, is it constitutional for states to prohibit parents from choosing religious options only? (more…)

The Douglas County, Colorado, School District is facing a lawsuit less than one month after launching a revamped voucher program. It's not school choice opponents that are suing this time, but three Colorado families excluded from the program because district rules now prohibit them from using vouchers to choose religious schools.

School district officials told the Denver Post that the new program was "designed to meet the state constitutional limitations as outlined by the Colorado Supreme Court in its ruling last summer."

But lawyers from the Institute for Justice representing the parents argue the new rules exclude and discriminate.

Last summer, a split state Supreme Court overturned the district's original voucher program, which allowed parents to choose any eligible private school regardless of religious affiliation. Citing the state's no-aid-to-religion provision, also known as a "Blaine amendment," a plurality of the justices ruled the program violated the state's constitution because parents could choose religious schools.

Appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court, lawyers for the district and parents argued that the state court's ruling would result in a program that violated the First Amendment and Due Process rights of parents.

The U.S. Supreme Court has not yet accepted or denied that petition.

School choice supporters have long argued that states must be neutral with respect to whether a participating school is religious or not. "Singling out religious schools is not even-handedness, it's discrimination," says Institute for Justice lawyer Michael Bindas. (more…)

Another court has rejected a lawsuit challenging tax credit scholarships after finding opponents of the program lacked standing to sue.

The latest ruling (flagged by Jason Bedrick of the Cato Institute) comes from Georgia, where on Friday, a Fulton County Superior Court judge issued a double whammy to school choice opponents when she tossed out the lawsuit after concluding the plaintiffs lacked legal standing and rejecting constitutional claims against the program.

In a ruling that echoes recent court decisions in other states, Judge Kimberly M. Esmond Adams held the plaintiffs lacked standing for two reasons — that taxpayer standing does not apply to privately funded programs, and that plaintiffs failed to show the program would harm them.

"Courts that have already considered whether a tax credit is an expenditure of public revenue have answered this question in the negative," the judge wrote in her 19-page decision, referring to the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Arizona v. Winn.

Adams also rejected the argument that plaintiffs, who include a parent and a grandparent of public-school students, would have had to shoulder a greater tax burden to pay for public education if the scholarship program were allowed to continue. "When these children leave public schools with a scholarship, the state no longer has to bear this expense," she wrote. (more…)