Back in February, the hashtag #ilovepublicschools trended on Twitter, but for reasons not intended by the originators. Many students used the hashtag as a vehicle to speak out about the bullying, homophobia and depression experienced by their peers.

Back in February, the hashtag #ilovepublicschools trended on Twitter, but for reasons not intended by the originators. Many students used the hashtag as a vehicle to speak out about the bullying, homophobia and depression experienced by their peers.

This startling phenomenon encouraged a deeper look at the data, as well as realization of the fact that anxiety and depression were maladies spreading among American teens before the pandemic.

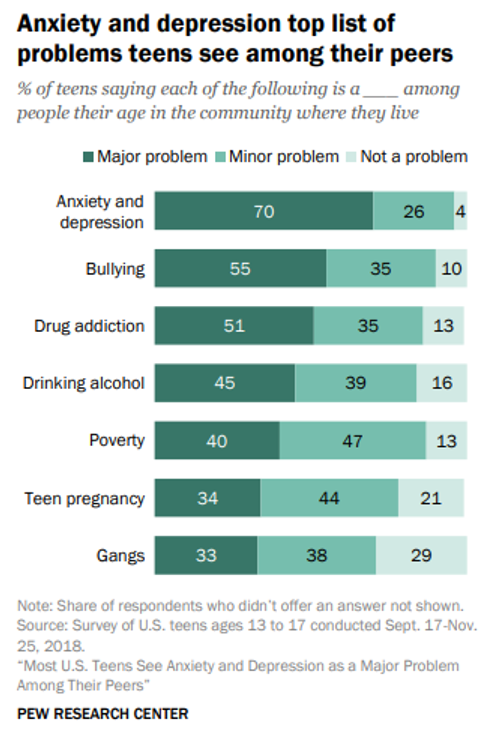

A fall 2018 Pew Center survey of teens 13 to 17 years old queried them on a variety of issues and asked them to describe those issues as “not a problem, a “minor problem” or a “major problem” among people their age in their community. Seventy percent of teens declared anxiety and depression a major problem; only 4 percent said it was not a problem.

Stark as these numbers are, they don’t suggest that the school system was the problem. Studies have linked teen use of social media to anxiety and depression, especially among teenage girls. Going forward, the idea should not be to assign blame but rather to improve matters.

For every teen in the Pew survey who said bullying was not a problem, 5.5 teens said it was a major problem, indicating a massive bullying issue. Indicative of another major issue is the fact that for every student surveyed who said drug addiction was not problem, four said that it was.

Many students seek transfer opportunities for social rather than academic reasons. A productive line of inquiry for researchers would be to compare the survey results on these topics for students who have had the chance to avail themselves of such opportunities to those who have not.

The opportunity to transfer out of a bad situation may not be a perfect solution in all cases, nor should ensuring it for all students represent the totality of our efforts. It almost certainly, however, improves the lives of a great many students.

When we (finally) get past the current epidemic, this previous one will still be there waiting for us.

Albert Einstein Academy opened in August 2018 to serve mostly LGBTQ high school students in metro Cleveland. Nearly 40 students enrolled and another 15 signed up to enter as ninth-graders this fall. About 80 percent of the students at the charter school identify as LGBTQ.

Sixteen-year-old Channing Smith of Tennessee killed himself after classmates circulated sexually explicit messages he exchanged with another boy. Fifteen-year-old Nigel Shelby of Alabama killed himself after peers bullied him over his sexual identity and school officials reportedly told him “being gay is a choice.” When 9-year-old James Myles of Colorado came out at his school, fellow students reportedly told him to kill himself. Tragically, he did.

In Florida, Elijah Robinson was harassed to the edge too. But for an educational choice scholarship that gave him an option – a safe, accepting private school – Elijah, 18, said he would no longer be alive.

Channing, Nigel, James and Elijah were students in public schools. That’s not a slam on public schools. It’s just a reminder, which I wish wasn’t necessary, that far too many LGBTQ students are tormented in far too many schools of all types.

Elijah Robinson, 18, a student at Foundation Academy in Jacksonville, Fla., experienced severe bullying at his assigned public school. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

It’s also a plea. LGBTQ students are two to three times more likely to experience bullying than non-LGBTQ students. I hope all of us who want to end that hostility will think twice about a narrative, recently buoyed by legislation filed in Florida, that casts programs that provide private school options as though they are inherently part of the problem. If the goal is ensuring the safety and affirmation of LGBTQ students – and not simply the tarring of educational choice – that doesn’t make sense.

Please consider what LGBTQ students say. According to the most recent survey by GLSEN, 72 percent of LGBTQ students in public district schools said they experienced bullying, harassment and assault due to their sexual orientation, compared to 68 percent of LGBTQ students in private, religious schools, and 60 percent in private, non-religious schools. For bullying, harassment and assault based on gender expression, the numbers in those three sectors were 61, 56 and 58 percent, respectively.

All those numbers are horrifically high. All lead to dark places. LGBTQ students are three times as likely as non-LGBTQ students to suffer from depression or anxiety. They’re twice as likely to experiment with drugs and alcohol. While 15 percent of non-LGBTQ high school students considered suicide over the past year, 40 percent of LGBTQ students did.

Educational options are not an antidote. But they can help.

In Florida, recent scrutiny over a relative handful of private schools that are not LGBTQ welcoming ignores a key point. Students are not assigned to those schools. Their parents can enroll them elsewhere. That’s often not the case for LGBTQ students suffering in assigned public schools. Elijah Robinson endured nearly two years of abuse in his assigned school before a scholarship gave him a way out. “If I had stayed,” he said, “I honestly think I would have lost my life.”

In Ohio, educators concerned about LGBTQ bullying in district schools opened a charter school for LGBTQ students. To be sure, some supporters had mixed feelings. As one parent told me, “We’re saying, ‘You’re so different, you need your own school’.” On the other hand, for many students at this school, having an option was literally a matter of life and death. “There’s a need,” said Henry, a transgender student who considered suicide in fifth grade, “for a school where people can feel like they belong.”

One day, I hope, all schools will be safe and affirming. In the meantime, it’s unconscionable to trap Elijah, Henry or any other student in any school that isn’t.