Signature School, a charter high school in downtown Evansville, Indiana, opened in 2002 as the state’s first public charter high school. It consistently ranks as one of the top high schools in the country according to a number of national publications, including U.S. News & World Report.

Editor’s note: This commentary appeared Monday on nydailynews.com.

Last Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court held that Maine’s exclusion of faith-based schools from a tuition-assistance program for students in rural school districts violates the First Amendment’s free exercise clause. The reason why is clear: “The State pays tuition for certain students at private schools — so long as the schools are not religious.”

Critics, including the dissenting justices, erupted in protest. Justice Sonia Sotomayor complained that the “Court continues to dismantle the wall of separation between church and state.” Justice Stephen Breyer predicted an increased “potential for religious strife.” Left-leaning commentators warned that the ruling might require states to operate religious schools.

Not true. This decision, in Carson vs. Makin, is the third decision in five years to invalidate the exclusion of religious schools from public-benefit programs. The opinion breaks no new doctrinal ground, but instead represents a straightforward application of what the majority calls the “unremarkable principle” that a “State violates the Free Exercise Clause when it excludes religious observers from otherwise available public benefits.”

Nor does the ruling require states to subsidize students attending private religious schools — except when it specifically chooses to subsidize students attending private secular schools. The majority makes clear that “a state need not subsidize private education...[b]ut once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

For the private-school choice program, Carson will have little immediate impact. Over half of states now have programs enabling children to attend a private school, and all but two of them — Maine and Vermont — sensibly and voluntarily include religious schools. The decision does, importantly, clear a path for the further expansion of private-school choice by defanging state establishment clauses that purport to prohibit support of religious schools.

But private-school-choice programs, which enroll fewer than 1% of U.S. schoolchildren, are only the tip of the school-choice iceberg. The elephant in the room is how this reaffirmed non-discrimination principle will now be applied to charter schools.

To continue reading, click here.

Amy Carson, left, and her daughter, Olivia, stand outside Bangor Christian Schools in Maine in November, before their case went before the U.S. Supreme Court. PHOTO: Linda Coan O’Kresik for Education Week

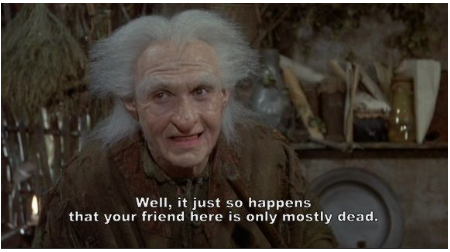

Blaine Amendments prohibiting the public support of religious schools, once used to bludgeon school choice supporters during legislative debates, is dead.

Or, at least mostly dead.

Or, at least mostly dead.

A 6-3 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court Tuesday determined that states cannot prohibit religious schools from participating in public benefit programs because they teach religious things.

Carson v. Makin follows a long line of decisions prohibiting states from interfering with, discriminating against or even promoting one religion over another. The 2020 Espinoza decision declared, “A State need not subsize private education. But once State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

Despite that ruling, Maine continued to prohibit religious schools from participating in a state program that allowed public dollars to pay for private school tuition. Lawyers for Maine argued that the state was complying with Espinoza because the prohibition wasn’t against the school’s status as a religious institution, but because the religious school taught religious things.

It was a distinction without difference.

“A neutral benefit program in which public funds flow to religious organizations through the independent choices of private benefit recipients does not offend the Establishment Clause,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the Court’s majority.

Roberts went further, explaining that prohibiting religious schools from participating violates the U.S. Constitution’s “Free Exercise” clause:

“The State pays tuition for certain students at private schools – so long as the schools are not religious. That is discrimination against religion. A State’s antiestablishment interest does not justify enactments that exclude some members of the community from an otherwise generally available public benefit because of their religious exercise.”

Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing a dissenting opinion, argued that the Supreme Court “continues to dismantle the wall of separation between church and state that the Framers built.”

Carson v. Makin, however, follows decades of legal precedents on government neutrality with respect to religion.

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Court defined the Establishment Clause beyond simply establishing a national church by declaring the clause prohibited the aid of one religion or even all religions. But the Court still upheld public bus fare reimbursements to parents sending their children to Catholic schools because the reimbursement was available to all.

Regarding New Jersey’s publicly funded programs, the Court ruled:

“Consequently, it cannot exclude individual Catholics, Lutherans, Mohammedans, Baptists, Jews, Methodists, non-believers, Presbyterians, or the members of any other faith, because of their faith, or lack of it, from receiving the benefits of public welfare legislation.”

Establishment Clause jurisprudence reached its apex with Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), which created the “Lemon Test” to determine if a program violates the Establishment Clause. The three-part test requires the program to have a secular purpose, to not advance or inhibit any particular religion, and to not excessively entangle government with religion.

In Lemon, the Court allowed state subsidies of textbooks, educational materials and even teacher salaries at private schools in Pennsylvania.

In subsequent decisions over the next half-century, the Court has taken an expanded view of religious liberty, diluting the "Lemon Test” that Justice Antonin Scalia colorfully described in Lamb's Chapel v. Center Moriches Union Free School District (1993):

“Like some ghoul in a late-night horror movie that repeatedly sits up in its grave and shuffles abroad, after being repeatedly killed and buried, Lemon stalks our Establishment Clause jurisprudence once again, frightening the little children and school attorneys of Center Moriches Union Free School District. …

“The secret of the Lemon test's survival, I think, is that it is so easy to kill. It is there to scare us (and our audience) when we wish it to do so, but we can command it to return to the tomb at will. When we wish to strike down a practice it forbids, we invoke it; when we wish to uphold a practice it forbids, we ignore it entirely.

“Sometimes, we take a middle course, calling its three prongs ‘no more than helpful signposts.’ Such a docile and useful monster is worth keeping around, at least in a somnolent state; one never knows when one might need him.”

Carson is the fourth significant decision this century to address the Establishment Clause with regard to education choice programs. In Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), the Supreme Court held Ohio’s voucher program was neutral with respect to religion.

In Trinity Lutheran (2017), the Court argued that denying grants for playground resurfacing simply because the institution was religious violated the Free Exercise clause.

Contrary to Sotomayor’s opinion, the latest string of cases probably gets us closer to the Founder’s original intent and further from the confusion over “separation of church and state” that began with Everson in 1947.

It is worth noting that federal and state funds subsidize pre-K and college educations at religious institutions, as well as healthcare at faith-affiliated nursing homes and hospitals. The courts have always treated these options as not violating “separation of church and state” because they provide public benefits (education or care) that just happen to be run by religious organizations.

There is very little public disagreement about these religiously affiliated providers, but neither is there the equivalent of a national teachers union with millions of dollars fighting against them.

The argument in Carson v. Makin is over Maine’s tuition assistance program, which pays for students in towns without a public school to attend another one of their choice — public or private — as long as it’s not religious.

This article appeared earlier today on bangordailynews.com. You can find a link to the full court decision here.

A conservative majority of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Tuesday that Maine’s ban on public funding for religious schools was unconstitutional and violated the free exercise clause of the First Amendment.

The 6-3 decision was expected based on questions from the justices at oral arguments in December and the appointment of three conservatives by former President Donald Trump.

“Maine has chosen to offer tuition assistance that parents may direct to the public or private schools of their choice,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the 45-page majority opinion, adding that the law “effectively penalizes the free exercise of religion.”

“Maine’s administration of that benefit is subject to the free exercise principles governing any public benefit program—including the prohibition on denying the benefit based on a recipient’s religious exercise.”

He was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett. Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan dissented.

“What a difference five years makes,” Sotomayor wrote. “In 2017, I feared that the Court was ‘leading us to a place where separation of church and state is a constitutional slogan, not a constitutional commitment.’ Today, the Court leads us to a place where separation of church and state becomes a constitutional violation.”

Despite concerns expressed by the Maine School Management Association and the Maine Education Association, supporters of lifting the ban don’t expect money to start flowing to religious schools without changes to other state laws that advocates for religious schools are now eyeing.

Those changes could come if Republicans win legislative majorities and the governor’s office this fall, but they’re more likely to come from further legal action in Maine and outside the state, according to Carroll Conley, executive director of the Christian Civic League of Maine.

The case, Carson v. Makin, challenged a state law under which districts without public high schools pay tuition so local students can attend a public or private school of their choice in another community, as long as it’s not a religious school. At issue was whether Maine was barring funds from going to religious schools because they would use the money for religious purposes or simply because they are religiously affiliated.

David and Amy Carson of Maine, pictured here with their daughter, Olivia, are challenging a decades-long policy that that limits to secular schools a state program offering financial assistance to families seeking education choice for their children.

Editor’s note: This commentary about Carson V. Makin, a U.S. Supreme Court case that will determine whether a state violates the equal protection clause of the United States Constitution by prohibiting students participating in an otherwise generally available student aid program from choosing to use their aid to attend schools that provide religious instruction, appeared Monday on bangordailynews.com.

The U.S. Supreme Court appears primed to overturn Maine’s ban on public funding for religious schools later this spring. But money won’t start flowing to Catholic and evangelical schools without changes to other state laws that advocates for religious schools are now eyeing.

Those changes could come if Republicans win legislative majorities and the governor’s office this fall, but they’re more likely to come from further legal action in Maine and outside the state, according to Carroll Conley, executive director of the Christian Civic League of Maine.

The league sponsored a meeting earlier this week to discuss the next steps in removing obstacles to public funding for religious schools in Maine.

The group’s preparations signal optimism from religious conservatives that a Supreme Court with a 6-3 conservative majority will rule in religious schools’ favor when it decides the Maine case. They also signal the potential for political battles over the state’s anti-discrimination laws as religious school advocates try to make it easier for public funds to flow to religious schools.

“We didn’t want to wait until June, when the decision is expected, to begin talking about what the next steps might be,” said Conley, a former principal at Bangor Christian Schools. “We want educational opportunities to be available to everyone regardless of their financial situation.”

To continue reading, click here.

The argument in Carson v. Makin is over Maine’s tuition assistance program, which pays for students in towns without a public school to attend another one of their choice — public or private — as long as it’s not religious.

This letter to the editor from Kirby Thomas West, a lawyer for the Institute for Justice who lives in Alexandria, Va., appeared Monday on washingtonpost.com. For additional context on Carson v. Makin, read reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s post here.

In her Dec. 7 opinion essay, “Taxpayers should not fund religious education,” Rachel Laser claimed that the issue before the Supreme Court in Carson v. Makin is whether taxpayers can be forced to fund religion.

Instead, the issue is whether, if a state creates a school-choice program, it can bar parents from choosing religious schools for their children. Notably, no one in the case is arguing that states have to create school-choice programs — only that if they do, they must not discriminate against religion.

In 2002, the Supreme Court recognized that school-choice programs, because they rely on parental choice and are neutral toward religion, do not violate the establishment clause. Curiously, Ms. Laser failed to mention this well-established principle of constitutional law.

(Or that school choice programs, including religious options, have been the norm for decades, including in D.C., with none of the “religious coercion” parade of horribles she warns about.)

Instead, Ms. Laser suggested that Carson could have a negative impact on state anti-discrimination laws that protect LGBTQ individuals. But such laws aren’t at issue in the case, which is evidenced by the fact that even if a school welcomes LGBTQ students, Maine says it need not apply to the program if it provides a religious education. The only discrimination at issue in Carson is religious discrimination.

Ms. Laser apparently wants the court to perpetuate this discrimination. For the sake of parents seeking better educational opportunities for their children, let’s hope she’s wrong.

Editor’s note: This commentary appeared Wednesday on The 74. For additional context on Carson v. Makin, read reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s post here.

Editor’s note: This commentary appeared Wednesday on The 74. For additional context on Carson v. Makin, read reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s post here.

Maine allows private religious schools to participate in its tuition benefit program for families that don’t have a public high school in their communities — except those that seek to instill religious beliefs in their students.

That caveat is at the heart of Carson v. Makin, argued before the U.S. Supreme Court Wednesday, a case that is likely to determine whether states can continue to ban religious schools from publicly-funded choice programs. Based on the justices’ questioning, experts said Maine, and states with similar laws, would likely no longer be able to defend them.

“This absolutely discriminates against parents,” Michael Bindas, a senior attorney with the libertarian Institute for Justice, who represents the plaintiffs, told the court. The state is discriminating against religion, he added, because decisions about whether a school is too religious to participate is “based on the decision of a bureaucrat in Augusta.”

Christopher C. Taub, Maine’s chief deputy attorney general, countered that the state’s program is “religiously neutral” and only seeks to give families free public education “roughly equivalent” to what they would get in a district school.

Wednesday’s hearing was the second time in two years the Supreme Court has considered whether public funds can pay for students to attend religious schools as part of school choice programs — an issue that public school advocates argue is a clear violation of the First Amendment’s separation of church and state.

In 2020, the court ruled in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, that the state could not exclude a religious school from a tax credit scholarship program simply because it was religious. The question in Carson takes the issue a step further, asking the court if officials can still ban such schools if they spend state money to teach religion. The fine legal parsing revolves around the issue of “status vs. use” — in this case, the difference between an institution that has a religious affiliation and one that uses public money to promote religion.

To continue reading, click here.

David and Amy Carson of Maine, pictured here with their daughter, Olivia, are challenging a decades-long policy that that limits to secular schools a state program offering financial assistance to families seeking education choice for their children.

The question of whether parents in Maine can send their children to religious schools using a K-12 state aid program will come another step closer to resolution this week when the nation’s highest court hears arguments in a case that could also influence whether other states adopt school choice programs.

The justices are scheduled to hear arguments at 10 a.m. Wednesday in Carson v. Makin, (Case No. 20-1088) which pits two families (a third has since withdrawn) against the state of Maine and its “town tuitioning” program that prohibits participants from sending their children to schools that include religious instruction. Arguments will be live streamed.

Though the case directly affects families in Maine, the ruling has national implications, said Michael Bindas, a senior attorney at the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit organization that represents plaintiffs in civil liberties cases. Bindas will argue the case before the high court this week.

Based on the number of amicus curiae, or “friend of the court” briefs – 33 in support of the plaintiffs and 12 opposed — the case has generated tremendous interest.

“Oftentimes when a school choice program is proposed, school choice opponents will run to the legislature and argue that they can’t adopt a school choice program because their state constitution prohibits public funds flowing to religious schools,” Bindas said.

He added that almost inevitably, “opponents will run to the courthouse to challenge it.”

“If the Supreme Court holds correctly … and says state law cannot single out and exclude religious options from these types of programs … then the argument that school choice opponents have consistently made in statehouses and courthouses will be removed once and for all.”

Bindas said a favorable ruling would assure states that allow religious school participation to be “legally bulletproof” while convincing states that were “on the fence” about such programs that they could safely move forward.

Since 1873, Maine has allowed families in areas without public schools to use taxpayer dollars to send their children to participating private schools. The controversy began in 1980 when the state’s attorney general issued an opinion that said allowing state aid to go to religious schools that promote “a faith or belief system” would violate the First Amendment’s ban on government establishment of religion.

The Maine Legislature responded by banning religious schools from participating in the state aid program.

The law withstood a challenge in 2002 when a Maine court upheld the state. However, the challenge of a ban of a Missouri church-affiliated preschool’s participation in a public benefit program to renovate playgrounds won a victory at the U.S. Supreme Court, which encouraged advocates of faith-based education and school choice.

A year later, school choice advocates scored a landmark victory when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue that religious schools cannot be excluded from school choice programs simply because they are religious. But the case addressed only the status of the schools and not whether they incorporated religious instruction or practices.

That issue was left unclear, explained Bindas, whose organization also represented the plaintiffs in that case.

Because Maine’s law bases its ban on religious instruction, lower courts hearing Carson v. Makin have sided with the state, which contends that “public education” means participating schools must offer only secular instruction.

“It is not the religious status of an organization that determines whether they are eligible to receive public funds, but the use to which they will put those funds that dictates the result,” the Maine Attorney General’s office, which is defending the state law, said in the brief it filed in Washington, D.C. “In excluding sectarian schools, Maine is declining to fund explicitly religious activity that is inconsistent with a free public education.”

Bindas said it should come as no surprise that religious schools do religious things. After all, that’s what makes them religious in the first place.

“One of our main arguments here is this is really a distinction without a difference,” he said. “Maine seems to argue although a state cannot discriminate against schools because they are religious, that it’s perfectly free to discriminate against them because they do religious things, and we just think that’s splitting hairs, and regardless of whether you call it used based or whether you call it status based, it’s unconstitutional all the same, and we fully expect the court will hold as much.”

The Supreme Court is expected to issue its ruling in spring or summer.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Charles J. Russo, Joseph Panzer Chair in Education in the School of Education and Health Sciences and research professor of law at the University of Dayton, appeared last week on The Conversation.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Charles J. Russo, Joseph Panzer Chair in Education in the School of Education and Health Sciences and research professor of law at the University of Dayton, appeared last week on The Conversation.

Since 1947, one topic in education has regularly come up at the Supreme Court more often than any other: disputes over religion.

That year, in Everson v. Board of Education, the justices upheld a New Jersey law allowing school boards to reimburse parents for transportation costs to and from schools, including religious ones. According to the First Amendment, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof” – an idea courts often interpreted as requiring “a wall of separation between church and state.”

In Everson, however, the Supreme Court upheld the law as not violating the First Amendment because children, not their schools, were the primary beneficiaries.

This became known as the “child benefit test,” an evolving legal idea used to justify state aid to students who attend religious schools. In recent years, the court has expanded the boundaries of what aid is allowed. Will it push them further?

This question will be in the spotlight Dec. 8, when the court hears arguments in a case from Maine, Carson v. Makin. Carson has drawn intense interest from educators and religious-liberty advocates across the country – as illustrated by the large number of amicus curiae, or “friend of the court,” briefs filed by groups with interests in the outcome.

To the school choice movement – which advocates affording families more options beyond traditional public schools – Carson represents a chance for more parents to give their children an education in line with their religious beliefs. Opponents fear it could establish a precedent of requiring taxpayer dollars to fund religious teachings.

To continue reading, click here.