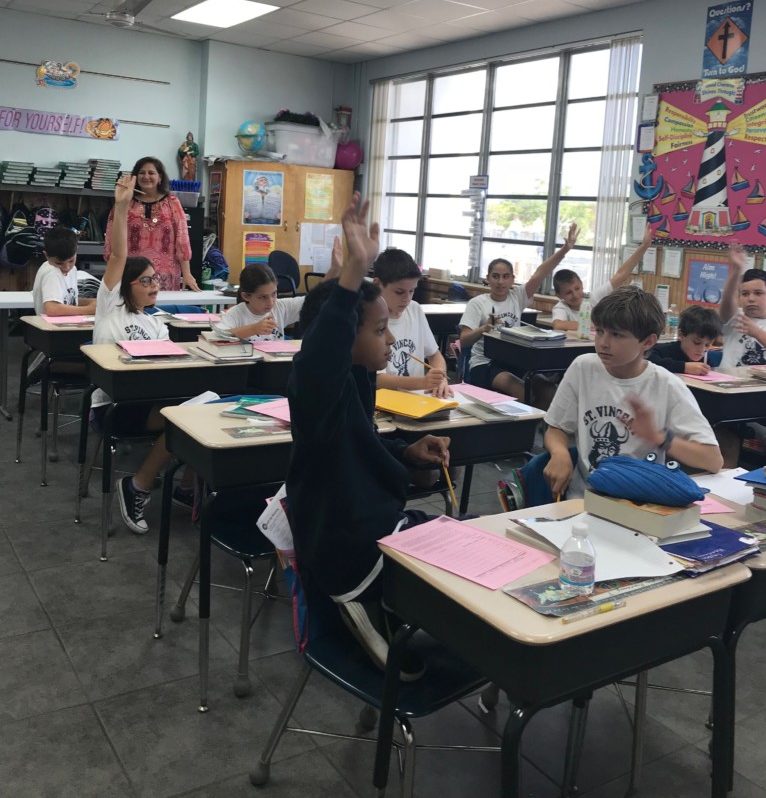

Students at St. Vincent Ferrer Catholic School learn about character development, which is taught in every area of the school.

What happens when you don’t tell the truth? What are the consequences? How does it affect your life?

Fourth-graders at St. Vincent Ferrer Catholic School in Delray Beach pondered these questions while reading the Newberry Honor-winning novel On My Honor. The story centers on a boy named Joel whose friend drowns while they are swimming in a dangerous river.

During the discussion, students were asked to weigh in on Joel’s decision to hide the truth about the drowning.

“Lying makes it worse,” one student chimed in.

Another student said: “You don’t value your friends until they’re gone.”

Students at St. Vincent Ferrer Catholic School were discussing Marion Bauer’s book because it is one of many that focuses on the development of character. At St. Vincent, the school's theme, Build a Better World by Building a Better You, is taught throughout the school: in classroom projects, curriculum and activities.

“We are under construction,” said Vikki Delgado, principal at St. Vincent. “Sometimes we fail, but we get up and try again.” (more…)

If one wishes a profound historical-dialectical account of the fate of religion in our governmental schools - all in 200 pages - make Craig S. Engelhardt’s new book, “Education Reform: Confronting the Secular Ideal,” your primer.

If one wishes a profound historical-dialectical account of the fate of religion in our governmental schools - all in 200 pages - make Craig S. Engelhardt’s new book, “Education Reform: Confronting the Secular Ideal,” your primer.

Engelhardt's guiding principle is constant and plain: If society wants schools that nourish moral responsibility, it needs a shared premise concerning the source and ground of that responsibility; and this source must stand outside of, and sovereign to, the individual. Duty is not a personal preference; if it is real, that is because it has been instantiated by an authority external to the person. In contemporary theory, the source of such an authentic personal responsibility is often identified in ways comfortable to the secular mind. There is Kant; there is Rawls.

But in the end, the categorical imperative and the notion of an original human bargain are vaporous. We go on inventing these foundations, but, in moments of moral crisis, such devices do not provide that essential, challenging, universal insight that tells each of us he ought to put justice ahead of his own project. Only a recognition of God’s authority and beneficence can, in the end, ground our grasp of moral responsibility.

This message is repeated at every turn to support the author’s practical and political conviction - that the child cannot mature morally in a pedagogical framework that deliberately evades its own justification. Engelhardt shows in a convincing way that the religious premise was originally at the heart of the public school movement. Americans embraced the government school for a century precisely on the condition that it gave expression to a religious foundation of the good life. When modernism and the Supreme Court gave religion the quietus in public schools, the system serially invented substitutes including “character education,” “progressivism” and “values clarification” – each of which in its way assumed but never identified a grounding source. The result: a drifting and intellectual do-it-yourself moral atmosphere - an invitation to the student to invent his own good. And all too many have accepted.

Engelhardt gives fair treatment to all players in the public school morality game. From the start he provides a generous hearing to the century-and-a-half of well-intending and intelligent minds who paradoxically frustrated their own mission of a religious democracy, first by shortchanging the unpromising Catholic immigrant, then - step by step - pulling the rug from under that transcendental dimension of education which alone could serve their wholesome purpose of training democrats. In this book, every historical player gets to give an accounting of the good he or she intended and the arguments thought to support it; of course, the rebuttals by Engelhardt are potent and even fun to read.

My first and less basic criticism of the book is its slapdash attention to the legal paraphernalia that will be necessary to school choice, if it is to serve the families who now enjoy it the least. (more…)

For many school choice supporters, enrollment growth across many sectors is reason to cheer. But new research may give policymakers pause about whether they're pursuing the options that result in the best academic outcomes.

William Jeynes, a professor at California State University, Long Beach, and a senior fellow at the Witherspoon Institute, found students in religious schools were, on average, a full year ahead of their peers in traditional public and charter schools. After controlling for parental involvement, income, race and gender, the students were, on average, seven months ahead.

The findings, recently published in the Peabody Journal of Education, were based on a first-of-its-kind meta-analysis of 90 studies that compared academic performance across the three sectors. Jeynes also found:

The implications for school choice, he said, are obvious. (more…)