The big news: In a closely watched case that could have national ramifications, the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruled a proposed religious charter school that the state approved last year violates the state constitution and charter school law.

What it means: The high court’s decision could halt the planned fall opening of the nation’s first religious charter school. The majority found that St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School was a governmental entity and state actor and therefore required to be non-sectarian. Six of the nine justices concurred with the majority, while one dissented and another partially concurred and partially dissented. Another justice recused himself.

It also said that Oklahoma’s approval of St. Isidore’s contract violates the state’s charter school laws, the state constitution, and the U.S. Constitution’s establishment clause and ordered the state to rescind its contract with St. Isidore.

The ruling also stated that a trio of recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions did not apply to St. Isidore’s assertion that prohibiting it from receiving public funding would conflict with federal protection of religious freedom.

In the court’s words: “St. Isidore cannot justify its creation by invoking free exercise rights as a religious entity. St. Isidore came into existence through its charter with the state and will function as a component of the State’s public school system. This case turns on the State’s contracted-for teaching and religious activities through a new public charter school, not the State’s exclusion of a religious entity.”

Case history: The statewide virtual charter school board approved St. Isidore’s application by a 3-2 vote. The decision prompted two lawsuits, one from a parents and faith leaders' group at the lower court level, and the other from state Attorney General Gentner Drummond, who asked the state Supreme Court to rule on the constitutionality. The high court’s ruling was on the attorney general’s lawsuit. The other case remains in the lower court. However, the high court’s ruling will likely render that case moot.

Why it matters: Charter schools are publicly funded but privately managed and have historically been classified as public schools. That makes them subject to federal requirements to be non-sectarian and comply with anti-discrimination policies. If St. Isidore is allowed to open, it would throw the doors wide open to efforts in other states to allow religious schools to directly receive taxpayer money. The Oklahoma Supreme Court ruling could tee up the case for the U.S. Supreme Court to decide whether charter schools are state actors. So far, the nation’s high court has declined to address conflicting lower court rulings.

Fraying alliances: The case pitted Oklahoma’s GOP leadership against each other, with Gov. Kevin Stitt and state Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters supporting St. Isidore and Drummond opposing it. Drummond called the decision “a significant victory.” Stitt expressed concern that the ruling sends a “troubling message” that religious groups are second-class citizens in the state educational system and that he hopes the U.S Supreme Court will consider the case. Walters also promised additional legal action. “This ruling cannot and must not stand,” he posted on X.

The Oklahoma lawsuit and related cases also divided the charter school movement, with the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools taking a strong stand against St. Isidore and Great Hearts Academies, a network of 40 classical charter schools in Texas and Arizona, taking the opposite position in a related case.

What they’re saying: The Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa, which sponsored St. Isidore’s application, issued statements expressing their disappointment with the ruling and suggesting plans to appeal.

“The educational promise of St. Isidore Virtual Catholic School is reflected in the 200-plus applications we have received from families excited for this new learning opportunity,” wrote Laura Schuler, senior director of Catholic education for the archdiocese. “Clearly, we are disappointed in today’s ruling as it disregards the needs of many families in Oklahoma who only desire a choice in their child’s education. We will remain steadfast as we seek to right this wrong and to join Oklahoma's great diversity of charter schools serving all families in the state.”

St. Isidore principal Misty G. Smith called the ruling “a setback” for the state’s K12 students and pledged not to give up hope “that court’s error may be corrected.”

Eric Paisner, acting CEO for the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, called the decision “a resounding victory.”

“All charter schools are public schools. The National Alliance firmly believes charter schools, like all other public schools, may not be religious institutions. We insist every charter school student must be given the same federal and state civil rights and constitutional protections as their district school peers. The Oklahoma Supreme Court’s decision reassures all Oklahoma families that their students’ constitutional rights are not sacrificed when they choose to attend a public charter school.”

Shawn Peterson, president of the Catholic Education Partnership, a national nonprofit organization advocating for school choice, didn’t take a position on the ruling but said he expects an appeal. A U.S. Supreme Court ruling in favor of St. Isidore could have implications for the 46 states, the District of Columbia Puerto Rico and Guam, which all have charter school laws.

“This case will be one of the more interesting school choice cases to watch as there is a great deal at stake, including some big policy questions and what actions state legislatures might take depending on the outcome of the ruling,” he said.

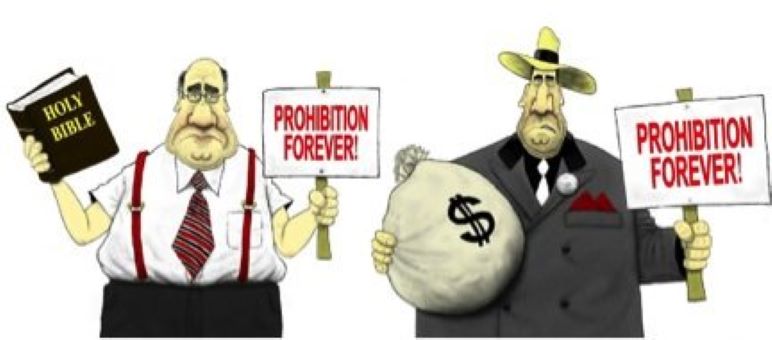

Last week we discussed the Oklahoma attorney general’s advisory opinion against enforcement of the state’s prohibition on religious charter schools. After reading up on the subject, I declared myself president of the “Religious Charter Schools are Permissible, Mandatory and a Bad Idea” Club. My view on this is not motivated by apocalyptic opposition (Europe has the equivalent of religious charters) but on practicality. The path to religious charter schools goes through years of litigation which, even if successful, will find itself (all too easily) thwarted by the Baptist/Bootlegger coalition.

Before proceeding let me again repeat it is a travesty that school finance systems discriminate against families desiring a religious education, and we need to end that discrimination. Moreover, what I am about to describe below is not how I want the charter world to operate. Far from it. Also, again, I am open to challenge on all of this. It should be debated vigorously. Okay, let’s go.

Russ Roberts often references the “Baptists and the Bootleggers” problem during interviews on his invaluable EconTalk podcast. It is an idea from the economic study of regulation that is easy to grasp: both Baptists and bootleggers support the prohibition on the sale of alcohol, but for very different reasons. Baptists oppose the sale of alcohol for religious reasons, whereas bootleggers, those who create/import/sell alcohol illegally, support prohibition as a means of limiting their competition. Bootleggers are going to sell alcohol regardless, but they make bigger profits by restricting others from competing with them.

Charter school authorization in most states around the country, including Oklahoma, obviously suffers from a Baptist and the bootlegger malady. The “Baptists” in this case are teachers’ unions and the rogue’s gallery of fellow travelers who don’t want any charter schools at all. They have a great deal of political power. The bootleggers are at least as much if not a greater problem. With regards to charters, bootleggers make claims of being greatly concerned with “quality authorizing” but one need only be realistic rather than cynical in noting that “quality authorizing” has much more to do with limiting competition for incumbent charters than it does “quality.”

Quality of course is in the eye of the beholder, and our means for assessing it in the context of schooling has been quite primitive. Also, the self-serving “quality” rules can look awfully arbitrary and stupid with the slightest bit of examination. For example, Arizona has a charter school with a rate of academic growth rate 98.6% above the national average, which would have been in danger of closure if Arizona lawmakers had been gullible enough to adopt a default five-year closure law (a favorite of charter bootleggers).

As Lisa Graham Keegan explained:

Moreover, Arizona’s “wild” charter journey led to many low-income, highly performing charter management organizations that can only be found in the Grand Canyon State. Many are community-focused and community-developed, which we all say that we want, but their first priority was on stabilizing the communities they grew from. In other words, they weren't very good academically to start—but they did transform their neighborhoods, and parents trusted these new schools with their precious children over many other options that went out of business due to lack of enrollment. Years later, many of them, like Academies of Math and Science, Mexicayotl Academy, and Espiritu Schools, are now among the top performing schools in not just the state, but in the country, and were highlighted in last week’s Education Equality Index. The thing is it took a decade to do that. And we Arizonans let it happen.

The Baptist/Bootlegger Charter Alliance has been, alas, devastatingly effective around the country. A whole string of states has passed charter school statutes in recent years — states like Washington, Alabama, Kentucky, and Mississippi. National charter school groups have sung the praises of these laws, but then, they produce few actual charter schools. In Kentucky’s case, no charter schools. The “Baptists” don’t want any charter schools, and the “Bootleggers” only want charters from their own organizations to operate, and the compromise lands on few charters opening.

Oklahoma, for instance, passed its charter law in 1999, and the Oklahoma Charter Schools Association lists 30 or so charters operating in the state, which looks to be a net gain of 1.5 schools per year. The Baptist/Bootlegger coalition effectively wants few if any charter schools to open, and it won’t be overly difficult for coalition members to agree on a dislike of charter schools teaching religion as truth.

Years of litigation awaits the would-be religious charter school operator, the result of which may vary across jurisdictions. Regardless of how that plays out, the Baptist/Bootlegger coalition will be waiting. They’ve had to be barely creative (900-page applications, etc.) to throttle charter school growth, and motivated by a shared distaste for religious charter schools, I’m guessing they will get insidious if necessary.

Nonetheless, there will be those who make the attempt. My advice to you dear reader: Don’t be one of them. Your energies will be better rewarded elsewhere. As Sun Tzu wrote: “A victorious general wins and then seeks battle, a defeated army seeks battle and then seeks victory.” Even if you survive the courts, the B/B Alliance will be there to finish you off.