Each KaiPod learning pod is led by a dedicated KaiPod Learning Coach to provide small-group and one-to-one academic support.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Michael B. Horn, co-founder of and distinguished fellow at the Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation, appears in the Fall 2021 issue of Education Next.

In a Historic House museum in Newton, Mass., nine children seated at three tables configured in a U-shape are each working on their own online lesson. After their 25-minute “Pomodoro” cycle – a time-management technique designed to optimize one’s ability to focus on a specific task – they break for a variety of outdoor recreational activities from badminton to Bananagrams.

The children are enrolled in KaiPod Learning, a program that offers small-group learning pods with access to virtual schools, in-person tutoring and support, and a variety of student-driven enrichment activities. The day I visited, many, but not all, of the students planned to join a yoga session in the afternoon.

KaiPod is among the startup pods that emerged from the height of the pandemic and that have so far survived.

In the summer of 2020, the frenzy around learning pods, also called microschools and pandemic pods, was high. As described in “The Rapid Rise of Pandemic Pods” (What Next, Winter 2021), families, including mine, were frenetically assembling or joining them out of a desire to preserve some in-person support, community, and normalcy in an otherwise abnormal year.

At the same time, equity concerns and parent shaming ran rampant. Educators, researchers, and the media worried about who would have access to these pods and whether low-income families would be left out of them.

A year later, the scene looks different. While the Delta variant has kept plans changing, people seem more interested in a return to in-person schooling. The conversation around pods hasn’t vanished, but it has quieted. Many families, including my own, pulled out of their pods last year because they found them unsustainable for any number of reasons.

And yet many pods that have an institutional structure behind them, rather than being fully parent-run, have survived. They are finding their niches and growing. Despite fears that pods would benefit only people in prosperous suburbs such as Newton, some of the most robust pod experiments have taken place in school districts disproportionately serving low-income and minority students.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: You can read a reimaginED interview with Debbie Veney, senior vice president of communications for the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, here.

Absent some delightful surge in fertility and/or immigration, it seems very likely that peak enrollment for America’s school districts lies in the past.

Years from now, district advocates may regard the years before the pandemic with nostalgia. Hopefully, people may think it strange, even primitive, that we once assigned students to schools by ZIP code. A 14-year-old and counting baby bust would not be easy to overcome in the best of times, and these surely are not the best of times for American school districts.

“Voting with Their Feet,” a new report from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, reinforces the impression the peak district enrollment has passed.

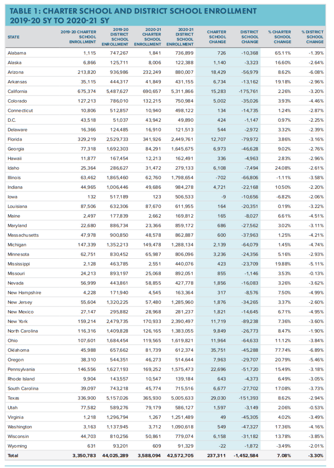

The Alliance tracked charter and district enrollment from 2019-20 to 2020-21. Nationwide charter schools gained 237,311 students while districts lost 1,452,584. All state charter sectors other than those of Illinois and Iowa gained students; all district systems lost students without exception.

District enrollment losses consistently outnumber charter gains, meaning that districts doubtlessly lost enrollment to kindergarten redshirting, private schools, home-schooling, dropouts and baby bust. Note, however, that all these things could have dragged down charter enrollment as well but didn’t manage it.

The real fun comes in examining the trends on a percentage basis:

With both the largest increase in charter school enrollment (77.7%!) and the largest decline in district enrollment (6.9%), Oklahoma parents win the prize for most restless parents.

Florida, meanwhile, saw a relatively modest increase in charter enrollment (3.9%) and modest decrease in district enrollment (3.2%). We are left to wonder what these numbers might look like if the Florida Education Association had prevailed in its effort to keep district schools from serving students in person.

Stay tuned and we’ll see what happens next.