Research indicates that the richest 20% of American families spent approximately $9,400 on enrichment for their children, such as tutoring, compared to $1,400 spent by the poorest 20%, as of 2006.

The COVID-19 pandemic has cast a spotlight on one of the significant barriers to equal opportunity in American education. Children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more dependent on in-school learning and have fewer resources to learn when schools are closed.

As lawmakers and school leaders work to prepare for the 2020-21 school year, including planning ahead for potential school closures and providing distance learning options, policymakers should consider new reforms to address longstanding inequalities in outside-of-school learning opportunities, which contribute to the achievement gap.

Background on the summer learning ‘slide’ and potential pandemic learning ‘dive’

In the past, researchers have found that children return to school after summer vacation having lost some of the learning gains made during the prior school year, and that children from poorer families regress more than kids from wealthy families. Over time, differences in outside-of-school learning opportunities and cumulative “summer learning slides” contribute to the academic achievement gap.

Many factors affect children’s learning opportunities when school is out of session. One difference is access to financial resources. According to Greg J. Duncan and Richard J. Murnane, the richest 20% of American families spent approximately $9,400 on enrichment for their children compared to $1,400 spent by the poorest 20%, as of 2006.

Reducing inequality in outside-of-school learning was an important goal before the pandemic. Now, it’s an urgent national challenge. More than 50 million children missed months of school in 2020, and the outlook for the upcoming school year remains uncertain.

The effects of pandemic-related school closures will be felt most acutely by disadvantaged children. Brown University researchers predict that children will return to school this fall having lost at least one-third of a typical year’s worth of learning in reading and a half a year’s knowledge of math. Importantly, they predict that these losses “would not be universal, with the top third of students potentially making gains in reading.”

In other words, the pandemic is increasing the achievement gap.

Facing the likelihood of periodic school closures and reduced schooling hours this fall, the United States risks growing and cementing an academic achievement gap for a generation of schoolchildren.

Investing in and expanding children’s savings accounts to promote equal opportunity

One option to address inequality in outside-of-school learning would be to invest in disadvantaged children’s education savings accounts and expand their allowable uses to include tutoring and enrichment expenses during the pandemic.

Several states, cities, and charitable organizations have created programs to invest in children’s savings accounts as a mechanism to reduce wealth inequality and promote saving for college. In their 2018 book “Making Education Work for the Poor,” William Elliott and Melinda Lewis describe how children’s savings account programs can promote equal opportunity. Elliot and Lewis reported that: “At the end of 2016, there were nearly 313,000 children with a CSA in 42 programs operating in 29 states, a 39% increase in enrollment from the previous year.”

Encouraging empirical evidence suggests that children’s savings account programs have positive effects for children and parents even during their early years. For example, Washington University conducted a randomized control trial in Oklahoma in 2007, providing $1,000 investments into the 529 savings accounts of approximately 1,350 children randomly selected. A control group of approximately 1,350 students did not receive investments. The “treatment group” received other benefits including savings matches and educational materials about savings for college.

The Washington University researchers studying the program over time reported that the treatment group benefited in multiple ways. In terms of financial benefits, “treatment children are 30x more likely than control children to have 529 college savings,” and the total amount of savings is 6x more than the control group.

The researchers also found that children receiving the investments demonstrated emotional-social benefits compared to the control group, particularly among economically disadvantaged children. “At about age 4, disadvantaged treatment children score better than disadvantaged control children on a measure of social-emotional development,” the researchers found, adding: “The effects of the CDA in these groups are similar in size to at least one estimate of the effect of the Head Start program on early social-emotional development.”

A short-term option for pandemic school closures and long-term strategy to promote equal opportunity

Most children’s savings account programs use state-managed 529 plans as the savings vehicles. 529s allow tax-free savings for college, K-12 tuition and job training expenses. Federal lawmakers have proposed expanding the allowable uses of these accounts to include tutoring and other enrichment costs. Combining reforms to invest in disadvantaged children’s 529 accounts while expanding their allowable uses has the potential to narrow the outside-of-school learning gap.

Another option would be to establish short-term ESAs to pay for tutoring and other outside-of-school learning costs. For example, Florida’s Reading Scholarship Account program provides children in grades 3 through 5 who are academically behind in reading with $500 in an account that can be spent on instructional materials, tutoring, or summer or afterschool programs focused on reading and literacy skills.

Florida’s program could be a model for how states and school districts encourage tutoring and remedial instruction for children affected by pandemic-related school closures. But the short window of time to establish, oversee, and manage new savings account programs for tutoring during the pandemic could be a challenge.

529 accounts are already overseen by state governments, which can ensure that funds are spent on allowed uses and not withdrawn for other purposes, particularly if government funding is being invested into these accounts. During the COVID-19 pandemic, 529 accounts would provide a practical vehicle for directing education funding to lower-income families to pay for tutoring and other services to make up for time lost while schools are closed without requiring states to establish and manage new ESA programs.

Beyond the pandemic, investing in disadvantaged children’s savings accounts has the potential to reduce wealth and educational inequality and promote equal opportunity.

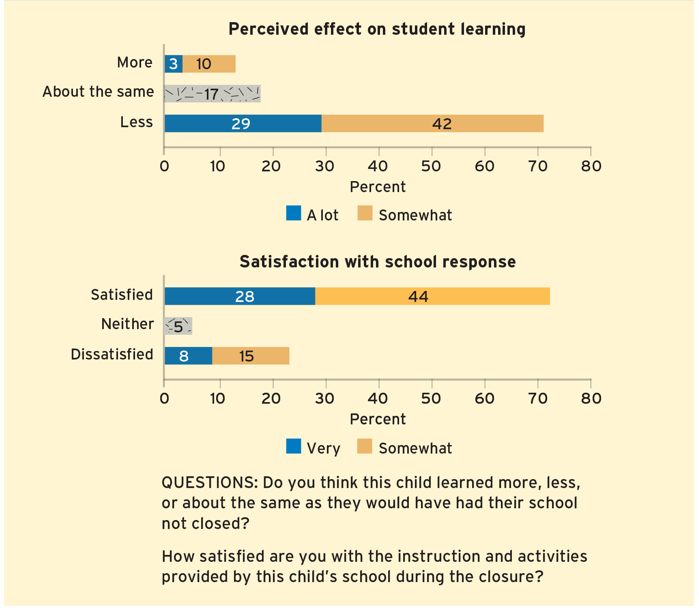

A new Education Next survey reveals 71% of parents perceived their children learned less during the pandemic than they would have had they remained in brick-and-mortar schools.

COVID-19 upended and changed the lives of millions of Americans this spring, forcing the nation’s schools to close and requiring a shift from in-person to virtual learning. In retrospect, what do parents think about the quality of instruction their children received?

Education Next surveyed them to find out. The results, released earlier this week, paint an interesting picture.

Among the 1,249 parents of 2,147 children surveyed, 71% said they thought their children learned less at home than they would have had they been in school. But surprisingly, 72% said they were satisfied with the attempt.

Black and Hispanic parents reported higher satisfaction with remote learning (30% and 32%, respectively), than white parents (26%). Charter school and private school parents (45% and 39%, respectively), reported higher satisfaction than parents whose children attended a public district school (29%).

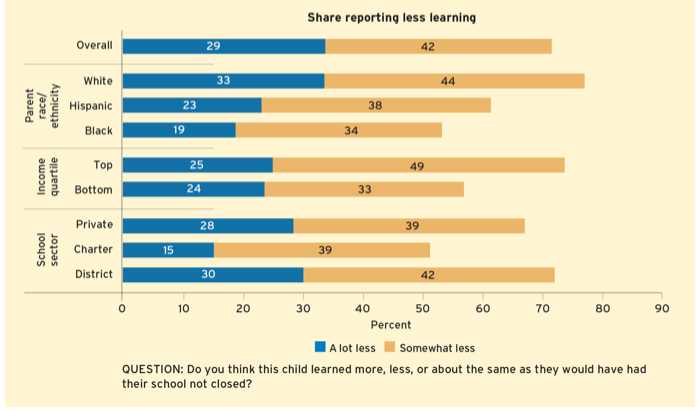

According to their parents, larger shares of the children of white respondents and children in higher income households learned less than they would have if schools had remained open than children of Black and Hispanic students and those in lower-income households.

Not all schools prioritized learning new content according to the survey. Overall, 74% of parents said their child’s school introduced new content, while 24% said the school focused on reviewing content students had already learned.

A large gap in perception persisted between high- and low-income families. Among low-income families, 33% reported that schools reviewed content students had already learned, compared to 19% of high-income parents.

Parents overall reported that one-on-one meetings between students and teachers occurred rarely, with only 38% saying such meetings occurred at least once a week. About 40% said one-on-one meetings never occurred.

Parents reported that class-wide meetings occurred more frequently, with 69% reporting class-wide virtual meetings with teachers occurred at least once a week.

Black parents reported their children spent more time per day (4.3 hours) on schoolwork than white parents (3.1 hours). Black parents also said their students suffered less learning loss than the parents of white students.

The survey also included a sample of 490 K-12 teachers who work in schools that closed during the pandemic. Teachers’ responses generally mirrored how parents described their children’s experiences with several exceptions.

Thirty-six percent of teachers said they met individually with students multiple times a week, compared with 19% of parents. Teachers also reported providing grades or feedback more often than parents. Meanwhile, teachers reported providing fewer required assignments than parents said their children received.

Parents and teachers generally agreed on how much students learned during distance learning, with teachers more likely than parents to say children learned less than they would have if schools had remained open.

The survey was conducted from May 14 to May 20 by the polling firm Ipsos Public Affairs via its KnowledgePanel. Respondents could elect to complete the survey in English or Spanish.

In this episode, Tuthill talks with a senior research fellow in education for the Christensen Institute whose work focuses on studying innovations that amplify educator capacity, documenting barriers to K-12 innovation, and identifying disruptive innovations in education.

In this episode, Tuthill talks with a senior research fellow in education for the Christensen Institute whose work focuses on studying innovations that amplify educator capacity, documenting barriers to K-12 innovation, and identifying disruptive innovations in education.

Tuthill and Arnett discuss the future of public education and the various “blended learning” models available for students today that leverage technology to customize education based individual needs.

In the midst of a worldwide pandemic that has disrupted education in unprecedented ways, both believe new learning models such as blending online learning with traditional brick-and-mortar education will help alleviate pandemic-related health concerns while serving as a long-term option more families will choose. They also discuss inherent problems of equity surrounding access and varying levels of parental and family involvement.

“As a parent I often found myself wondering, "what are my kids really learning?... I can make this learning much better for them if we can talk about it (at) the dinner table … right now necessitates a greater interdependence between home and school."

EPISODE DETAILS:

· COVID-19 as an accelerant to changes in public education

· How technology can be used more assertively to enhance education productivity and reduce inequity

· Types of learning best delivered face to face versus delivery online and best practice for optimizing lesson plans

· How to help parents meet their growing role in public education

· How public education can begin to unbundle services to better serve communities

LINKS MENTIONED:

Blended learning models that can help schools reopen

Florida students who attend private schools on state scholarships will be allowed to participate in any innovative learning options their schools offer during the first half of the academic year without losing their financial aid, according to new rules issued today.

Florida students who attend private schools on state scholarships will be allowed to participate in any innovative learning options their schools offer during the first half of the academic year without losing their financial aid, according to new rules issued today.

As part of an emergency executive order governing the reopening of all schools in August, Florida Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran is allowing for flexibility in the state law requiring all scholarship students to “maintain direct contact with teachers” to keep their state scholarships.

According to the executive order, “the temporary and limited nature of the waiver of statutes and rules is necessary to respond to the pandemic.” All schools, including charter and private schools, must offer traditional on-campus instruction five days per week for families who want it, but schools also may offer a distance learning option to accommodate students whose families do not feel comfortable sending them back to campus.

News of today’s order came as a relief to private school leaders who worried that students unable to attend school in person might be required to forfeit their state scholarships.

“I think this is wonderful,” said Pam Tapley, head of school at Pace Brantley School, a private K-12 school that serves children with learning differences in the central Florida community of Longwood. “There’s a spike right now, and what does that mean for us? Having that executive order allows us the opportunity to switch gears if necessary. This will really take a worry off parents.”

The school requires every student to have an iPad as a condition of enrollment to accommodate online learning. That practice enabled the school to transition quickly to online education once all school buildings were closed in March.

The order stipulates that schools choosing to offer innovative learning must submit a plan to the Department outlining how these arrangements will work. All schools should include details on how progress is monitored, how students with special needs or who are English language learners will be served, and how achievement gaps will be closed. Schools that plan to offer only onsite instruction do not have to submit a plan.

Jacob Oliva, the DOE’s chancellor of public schools, said such innovative plans are expected to meet certain standards allowing for student and teacher interaction. The plans also must indicate how districts will take attendance and how student progress will be documented.

“We want to be sure we’re not just sending home packets on a Monday and collecting them on a Friday,” he told attendees of a webinar today on the executive order.

Oliva acknowledged that only about one-third of parents responding to a DOE survey indicated a strong desire to send their children to in-person classes five days a week in the fall. Many families expressed a desire for other education options, such as live online lessons.

The order continues the procedures followed in March when the state temporarily waived in-person requirements for scholarship students as the pandemic forced all schools to pivot to distance learning almost overnight.

Parents at the Academy of Our Lady of Peace in New Providence, N.J., organized to raise money to reopen the elementary school after it and seven other Roman Catholic schools in the Newark area were slated for permanent closure.

The next round of pandemic relief funding for K-12 education should set aside 10% to help private school parents and students, in line with the proportion of private school students across America, say more than 150 private school and school choice groups in a new letter to Congressional leaders.

More specifically, the groups argue that private schools reeling from the challenges of distance learning and declining enrollment should get indirect assistance from emergency tuition grants for low-income and middle-class families, and from creation of a federal tax credit program for scholarship funds.

“With many families suddenly facing unexpected and immense financial challenges with income loss, they may not be able to make required tuition payments,” the groups wrote. “We believe that families seeking the best education opportunities for their children, especially those facing difficulties due to COVID-19, should be supported.”

The letter was signed by 156 groups, including Step Up For Students, the nonprofit scholarship funding organization that hosts this blog. That’s up from 48 private school and school choice groups that made a similar pitch six weeks ago. And it comes as Congress considers the next round of federal relief, including potentially tens of billions of additional dollars for K-12 education.

To date, little federal relief for K-12 education has offered meaningful help to private schools, despite increasingly anxious stories about their plight. In coming months, more than 100 Catholic schools are expected to close, and hundreds if not thousands of other private schools are likely to be hurt too. Growing numbers of parents are telling private schools they won’t be able to afford tuition in the fall, and surveys suggest many private schools fear the recession and continued closure of brick-and-mortar operations could bring their demise.

Public school traditionalists have pushed back against efforts to devote even a slightly bigger share of current relief to private schools. But the letter echoes the argument made by choice advocates (like here and here), that helping private schools will by extension help hard-hit public schools.

If 20% of private school students end up enrolling in public schools, the letter says, taxpayers would have to find another $15 billion to absorb them. Given other operational and logistical challenges, that flood would arguably come at the worst possible time.

Editor’s note: Policy expert and redefinED guest blogger Jonathan Butcher wrote this commentary for the Goldwater Institute. It appeared June 18 on the institute’s blog, In Defense of Liberty.

Editor’s note: Policy expert and redefinED guest blogger Jonathan Butcher wrote this commentary for the Goldwater Institute. It appeared June 18 on the institute’s blog, In Defense of Liberty.

As students around the country begin summer break, the status of K-12 school operations is different from state to state—even district to district in some places. Here’s what parents need to know:

Reopenings have started.

Lawmakers in Montana and Wyoming have allowed school buildings to reopen (some schools are currently holding in-person classes). In Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Texas, school buildings are open for summer school. Last week, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis released a plan to reopen schools in August at full capacity.

These decisions should be made as locally as possible. Federal guidance from the Centers for Disease Control will be broad and cautious, not specifically tailored to meet the needs of every school. The national perspective offers general guidelines, but state and district officials must evaluate local needs.

Parents may not send students back.

Surveys indicate parents are still concerned about the pandemic and school officials’ choices in the face of changing conditions. Between 40 and 60 percent of parents have said they are considering homeschooling in the fall. These numbers should be a sign to district administrators that were slow to provide any instruction between March and May that they need to restore parents’ confidence in their child’s school.

Some districts and charter schools, in particular, moved quickly to provide remote learning, but reports reveal that thousands of students in large cities never interacted with teachers. School district officials in Fairfax County, Virginia, prepared no virtual instruction, while district administrators in Pennsylvania, told teachers not to help any students online until the district approved the activity. Meanwhile, students across Detroit and Los Angeles did not touch school assignments during the quarantine.

Parents and students need stability. Officials need to tell parents they are preparing now to reopen at full capacity, barring local COVID-19 outbreaks. Educators should also tell families they will evaluate students at the beginning of the semester to determine where students stand academically.

State and district policymakers and special interest groups such as teacher unions are demanding more money from Washington before schools reopen, but they should be concerned first with regaining parents’ trust. The financial recession will impact all schools, likely prompting school administrators to lobby for spending increases. These officials must demonstrate now that they are putting student needs first—students that have already missed months of instruction.

Private schools are important parts of their communities, and they are suffering.

Private schools are a lifeline to 5.7 million students around the country, but the pandemic and ensuing recession are forcing them to close—permanently—by the dozen. (The Cato Institute is tracking the closings.) Federal spending is not a trust fund to rescue schools. For public and private schools, such spending expands federal influence, which will come back to haunt these communities when federal lawmakers decide standard operational requirements such as testing and admissions criteria are in order.

State lawmakers can help by creating new opportunities for students that want to access private schools, such as Utah’s new scholarships for children with special needs or a proposal in North Carolina to provide scholarships to students from families that received federal relief payments at the pandemic’s outset. Broad eligibility is essential.

Meanwhile, U.S. Department of Education guidance says districts should use federal relief spending on services for K-12 schools to help all private school students in low-income areas. Again, better to not expect federal assistance, but if the resources are already being disbursed, the spending should help all students.

Some public-school officials are resisting, but if a private school closes and parents decide to homeschool, even under difficult conditions, public schools have a tough sell at the ballot box. Traditional schools should not miss an opportunity to demonstrate how valuable their services can be.

Public and private school students, especially those struggling to keep up, cannot afford to lose another semester. The lesson from the Pandemic Spring is that we cannot wait for the virus to disappear before we start living again.

Kindergartner Sofia Ascencio wears her graduation gown to a farewell parade at St. John the Baptist Catholic School in Napa, which is closing after 108 years due to declining enrollment and the coronavirus pandemic.

We can always use more examples of teamwork. Public-school officials have such an opportunity before them as schools prepare to re-open and should to seize it – and resist calls to resort to turf warfare.

In March, Washington provided additional resources through the CARES Act so that school districts can help their schools and private schools with COVID-19-related needs. Federal officials began distributing the money just as some public-school officials objected to federal guidance on how school administrators were to use the spending.

Before taking sides, an honest—perhaps generous, in some places—assessment of school district activities during the pandemic is that school responses across the U.S. were uneven. When school buildings closed, some public officials either waited weeks to deliver any instruction to students quarantined at home or failed to do so at all. Those who observers say responded quickly, such as the ones in Miami-Dade and charter schools in low income areas in Philadelphia and Arizona, deserve credit, but by the middle of May, reports indicated that more than two-dozen large districts across the U.S. had made online work meaningless by not grading students.

The lackluster response helps to explain why recent polls have found that 40-60 percent of parents are considering homeschooling this fall. Fear over another outbreak after students are back in close quarters may also be on parents’ minds, but school districts that failed to follow through during the pandemic has some parents wondering if they could do better themselves.

School districts have another chance to earn the confidence of families, though. In April, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said that districts should use CARES spending to provide services to private schools based on a private school’s total enrollment, not just the number of students in need attending private schools.

Things get technical quickly with this provision, but the usual suspects in unions ignored the details and said districts should ignore the guidance, claiming “this funnels more money to private schools.”

In reality, the main federal education law, now called the Every Student Succeeds Act, says that low-performing private school students in low-income areas can get help from public schools. This part of the law, called “equitable services,” includes tutoring and summer school. Private school officials must work with public school leaders to determine how the help will be delivered.

With the new COVID-19 spending, the Education Department said that equitable services should help all students—public and private—not just struggling students. Why? Because CARES Act money is emergency spending, not annual spending for students in low income areas.

Just as with the delivery of traditional equitable services, private school leaders and students will make these plans with local district schools—giving traditional schools the chance to show private school families that public schools can help them.

Districts have another reason to make the most of equitable services now: As groups such as Ed Choice have explained, if private schools close, taxpayers could see K-12 costs increase during the recession.

We are still plumbing the depths of a financial crisis, and smart districts are already cutting costs to prepare for next year. Larger classes at a time of limited services will not appeal to parents.

Indiana and Maine have said they will not abide by the guidance. Private schools in Pennsylvania and Colorado are challenging their state agencies’ interpretations, which are also limiting access for private school students.

Meanwhile, South Carolina Superintendent of Education Molly Spearman said the state will follow the federal guidance. In a letter to private school educators, she said, “Public and private school leaders working together can address the true needs of South Carolina’s education system caused by COVID-19.” Florida officials have said they will also follow the department’s interpretation. Secretary DeVos said her office is working on an official rule.

Public schools should not view equitable services during the pandemic as a new front in some perceived brawl. All students and schools need help now, so public schools have a chance to be the hero. Perhaps district actions in good faith here could be used to sway public opinion during a recession should districts try to appeal to state taxpayers for more resources.

But if not, and should districts leave private schools to wither, expect more polls showing parents are ready to keep students home—even if private schools close.

Explain that to taxpayers.

Samyra Santana, right, her husband, Gerson Reina, and their daughter, Samira, found a home at St. Joseph Catholic Church and St. Joseph Academy in Lakeland.

Editor’s note: Special thanks is extended to Fernanda Murgueytio, a member of Step Up For Students’ Advocacy and Civic Engagement team, for invaluable assistance in reporting this story. Fernanda helped with interviews and translated them from Spanish to English.

LAKELAND, Fla. – Two years after government thugs forced her family to flee their home, Samyra Santana googled “Catholic church near me.” She and her husband and daughter were 1,700 miles from the madness that upended everything, trying to start over in this city of lakes and live oaks.

The screen read, “St. Joseph Catholic Church.” As fate would have it, the first person Santana met when she drove over was a building manager who spoke Spanish. Before long, her family had a church, a school – and a warm, inclusive community to build a new life in.

Then, bam.

On May 21, the Diocese of Orlando announced that due to complications from COVID-19, St. Joseph Academy was closing. Santana said the news made her physically sick.

“It felt like I was losing my home again,” she said.

St. Joseph Academy was the oldest private school in Lakeland, a city of 110,000 an hour from Orlando. It could have been a role model for diversity, with students of color making up half its enrollment and the children of doctors, lawyers and truck drivers learning side by side. Instead, it’s another poster child for the demise of private schools in the Time of Coronavirus.

In coming months, more than 100 Catholic schools are expected to close. Hundreds if not thousands of other private schools will be hurt too. The recession is taking its toll on enrollment and philanthropy. And Covid-19 is creating unprecedented challenges for private schools trying to maintain, via online platforms, the culture and community that makes them special.

Articles like this, this and this are spotlighting the plight of private schools as Congress considers pleas for relief. But cold facts alone can’t express what’s at stake if these schools are allowed to collapse.

Take it from a family that once lost it all: “St. Joseph’s Academy became a place where we feel we belong from the heart,” Santana said. “Now … our hearts are broken.”

***

In Venezuela, Santana was a public school teacher and owner of a thriving dance academy. Her husband, Gerson Reina, ran his own small business, distributing baked goods for a multi-national company.

In 2014, Santana and an apprentice were leaving a mall when men rushed out of nowhere. They put the women in a car and blindfolded them.

“Don’t go back to my school. Don’t go back to my academy,” Santana said they told her. “They told me so many times, they’re going to kill me, they’re going to kill my husband.”

Santana is a ballet dancer by training. She’s trim and athletic, modest and soft-spoken. It’s hard to imagine her as an enemy of the state, but she ran afoul of the regimes of Hugo Chavez and his successor, Nicolas Maduro. Chavez supporters told her, when she directed a government dance studio, that she had to praise the president and pledge support during recitals. Santana refused. The government fired her.

So Santana started her own school. More than 100 families followed her, and she encouraged directors of other government studios to do the same. They did, infuriating Chavez supporters.

One day, some of them followed her home and attacked her. The beating led to a miscarriage.

Fast forward to the kidnapping. After hours of driving, the men dropped Santana off in an unfamiliar place in another city. She was alive. But life in Venezuela was over.

***

In “Lost Classroom, Lost Community,” University of Notre Dame law professors Nicole Stelle Garnett and Margaret F. Brinig underscore the quiet power of Catholic schools.

For generations, Catholic schools in America have ably served immigrants and low-income families. They continue to propel low-income students into the middle class and save taxpayers untold billions. But that’s not all they do.

Analyzing crime data in Chicago, Philadelphia and Los Angeles, Garnett and Brinig found when Catholic schools disappear, crime rates rise and social bonds fray. “Catholic school closures lead to elevated levels of disorder and suppressed levels of social cohesion,” they wrote.

That’s not to suggest the fetching bungalows around St. Joseph are in for a rash of burglaries. But it does show Catholic schools bring value not just to families they serve, but to communities they help anchor.

Other high-quality schools draw people of shared interest too. They inspire them to work together for the common good.

Sometimes, in the process, they make people whole again.

***

They travelled light. Just a few suitcases. Santana said selling the house or packing everything would have drawn suspicion, which could have led to darker outcomes.

Santana’s daughter Samira, now 12, wanted to take her stuffed animals, particularly a stuffed bunny. But there was no room and no time. “We left everything,” Samira said.

The family trekked to Miami with $2,000 to start a new life. Santana’s husband found work as a cashier in a gas station, but nothing that fit his skill set.

Santana fell into a funk. “My body was here, but my mind was in Venezuela,” she said. “I was thinking about my family, my students, my friends. I didn’t say goodbye.”

Santana’s husband expanded his job search, and finally got a bite: Frito Lay had an opening in Lakeland.

The family didn’t know anybody in Lakeland. But they liked the tree-covered neighborhoods and the respite from South Florida concrete. The peace and quiet offered a welcome contrast to the clang of pots and pans that characterized protests in Venezuela.

Hope began to grow.

***

Samira Santana, 12, will attend St. Anthony Catholic School in Lakeland in the fall.

The family began attending St. Joseph in 2016. Santana began volunteering at the church and working in the preschool, an aide in the faith formation program. She said she could she feel her mind and heart healing. “I could be myself again,” she said.

Santana wanted the same for her daughter.

Samira said the students in her neighborhood school didn’t understand her and didn’t really talk to her. They made fun of her accent and mocked her roots. “They looked up Venezuela and they said, ‘Oh she comes from a poor country.’ ”

In 2018, Samira enrolled in St. Joseph Academy. Then a sixth grader, she worried she wouldn’t make friends. But on the first day in the lunchroom, “The kids were like, ‘Come sit with us.’ “

“It felt,” she said, “like I belonged there.”

Samira made good grades, sang in the choir, discovered a love for musicals. She stepped up to play the mayor of Whoville in “Seussical” and the caterpillar in “Alice in Wonderland.” Now the once-shy girl who lost her country rocks a NASA T-shirt and loves astronomy.

After everything Samira’s been through, reaching for the stars isn’t so hard.

***

This fall, Samira will be an eighth grader at St. Anthony, another Catholic school in Lakeland. She only knows one other St. Joseph student making the switch. “St. Joseph was like having another family,” Samira said. “I don’t want to lose them.”

Santana knows she is fortunate Samira can attend another Catholic school, even if it’s 40 minutes from their home. But it doesn’t diminish the fact St. Joseph is gone.

“I think when you have lost so much, you cling more to what little or much you have gained,” Santana said. St. Joseph “was a gain for us as human beings.”

What better way to sum up what’s been lost. And what can still be saved.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Bruce Hermie, director of school partnerships for the American Federation for Children, appeared earlier this month on the AFC blog.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Bruce Hermie, director of school partnerships for the American Federation for Children, appeared earlier this month on the AFC blog.

Widespread school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic have launched many school leaders into uncharted waters.

Educational strategies have been executed on digital or distance platforms and budgets that were set in January are now requiring reassessment and, in some cases, painful cuts that will have long term ramifications on school vitality and growth. Now, more than ever, it is imperative school leaders look to the future and give consideration of not only how to survive their immediate reality, but find the inspiration and courage to help their schools emerge stronger and more effective to meet the multi-faceted needs of their students, teachers, and communities.

It is said that fortune favors the bold. If there was ever an opportunity for school leadership to rethink their approach and redeploy resources to meet the challenges ahead, that time is now.

As each school is its own unique learning organization, the search for one magic panacea that will work for a flawless and safe path forward for every school is fool’s gold. School leaders who understand the nuances of their schools and communities will be best served assessing their own resources, finding what avenues for instruction and safety are possible, and pairing that to guidance being given by health professionals to set forward a plan that meets the needs of their students and faculties in a multi-pronged approach.

Most school leaders have come to the conclusion they must prepare for in-person, hybrid, and online learning scenarios. Instead of guessing at which of the three could occur, why not empower students/parents and teachers to choose the method of delivery which best fits their own realities?

A recent poll that appeared in USA Today found that one in five teachers reported they may not report back for the start of the school year. A separate poll indicated 60 percent of parents said they were willing to pursue at home learning options for their children as opposed to returning them to in-person classes when schools resume in the fall.

This information should serve as notice that options for mode of education are more necessary now than ever.

In schools where multiple classes per grade exist, why not embrace flexibility and give families and teachers the option? If schools were to designate one or two teachers to be the “online” teacher for their respective grades, families could then choose whether distance learning or in-person education best fits their needs and comfort level.

Teachers at risk from a health standpoint would also have the ability to continue to work and educate from the safety of their home while those who crave a return to in-person instruction can return to campus. One benefit of committing to such a model full time is it allows for professional development and evolution of distance learning strategies and competencies should the need to pivot to full-time online instruction for all students occur again.

Schools may find other unexpected benefits in diversifying the way they educate. In the short term, diversification will lend to a smaller number of in-person students on campus, making the adherence to CDC guidelines for safety more manageable. In the long-term, schools may see an increase in enrollment as families who seek this flexibility for a myriad of reasons including health, special interests outside of the academic realm that require flexible scheduling, and a simple desire by parents to be more deeply involved in the education of their children.

In a time filled with many stresses and an unknown future for many school leaders, the best thing to do is what always must be the priority for any educator: serving the children effectively, keeping them as safe as possible, and allowing them the room to grow into capable young women and men who have a positive impact on society.

Schools that find ways to do this effectively and have courage to move past the status quo will thrive while those who fail to be imaginative struggle to regain a lost normal.

Graduate training in the social sciences teaches students to think in terms of a multi-variable world. Humans naturally gravitate toward simple explanations of reality, such as X caused Y, when in fact isolating the impact of X on Y with reliability is very difficult.

Graduate training in the social sciences teaches students to think in terms of a multi-variable world. Humans naturally gravitate toward simple explanations of reality, such as X caused Y, when in fact isolating the impact of X on Y with reliability is very difficult.

Random assignment studies are the most useful in this regard, but these sorts of studies are difficult and expensive to arrange, and many policies do not lend themselves to random assignment. Many times, we have little choice but to make decisions based upon lesser evidence.

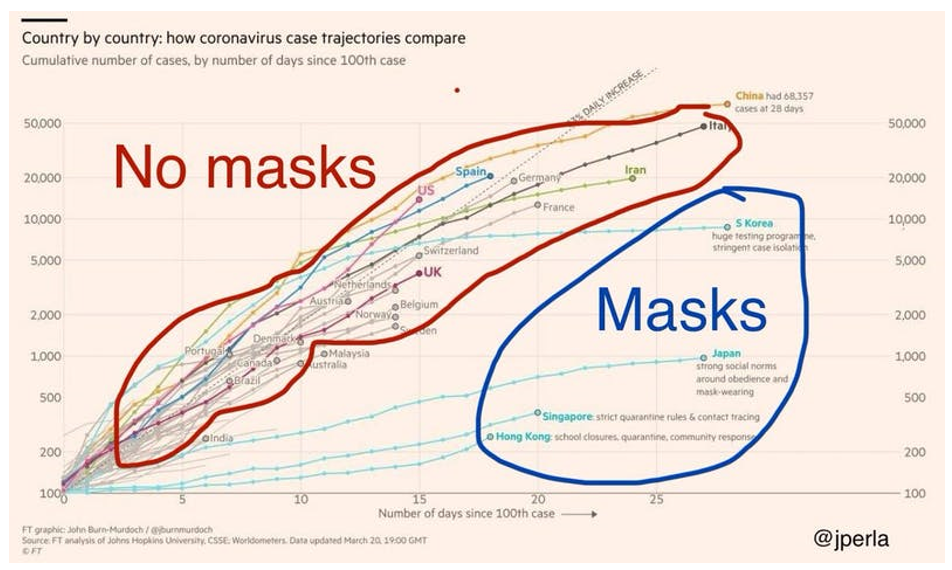

The social scientist is trained to look at technology leader Joseph Perla’s chart above and say, “We shouldn’t assume that South Korea, Japan and Singapore are having a good pandemic because of masks. It could be something else, or it could be multiple other factors. Masks could actually be bad.”

This is all potentially true. Moreover, unless you are willing to randomly assign people to wear masks in public and prevent the control group from wearing them, you cannot know for sure.

Policymakers, on the other hand, do not have the luxury of epistemological nihilism. They must make decisions, almost always based upon incomplete or otherwise imperfect information.

President Harry Truman once said: “Give me a one-handed economist. All my economists say, 'on hand...', then 'but on the other ... ’”

So, while the social scientist looks at this chart and suspects foul play, the pragmatist looks at it and says, “Well, there could be other things going on, and masks could still be playing a positive role.”

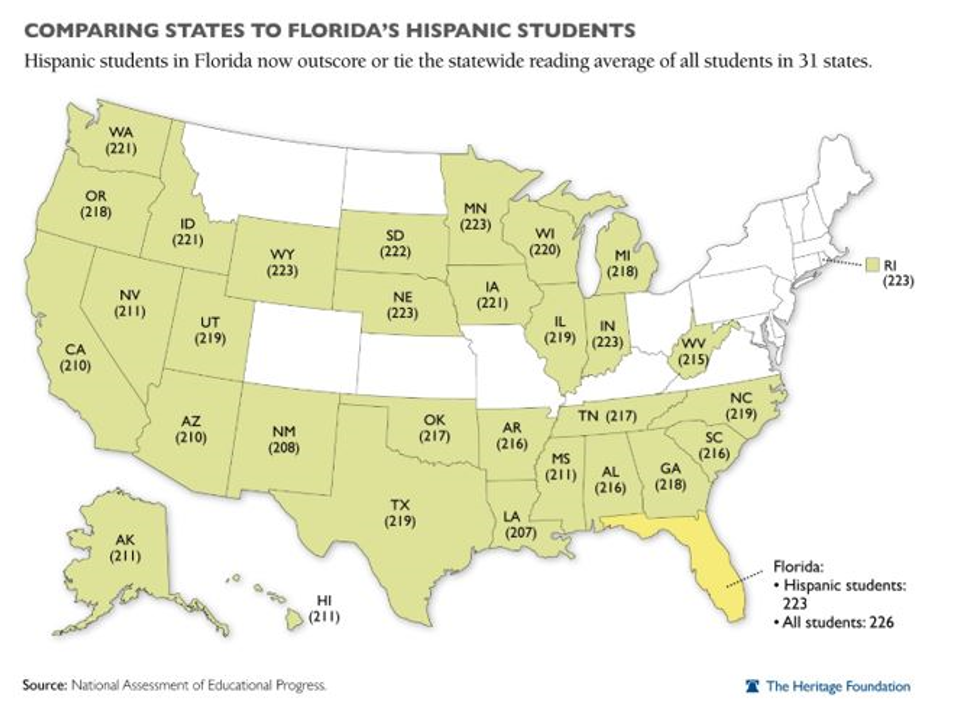

K-12 policy also gets made in a chaotic world with multiple policy changes occurring at the same time. Back when I collaborated with the Heritage Foundation to produce the map below comparing the fourth-grade NAEP scores of Hispanic students in Florida to the statewide averages for students across the country, critics raised the social science objection: “You don’t know which Florida policy led to the increase,” was the essence of the complaint.

This was entirely correct from the point of view of the social scientist, but the pragmatist in me required me to say: “Since we don’t know which of the many reforms in the Florida cocktail led to the improvement, don’t take any chances – implement all of them.”

Likewise, someone might want to study everything Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore have done to prevent the spread of COVID-19. It is not necessarily the same approach. But right about now, encouraging people to wear masks in public is looking like a pretty good idea, not dissimilar from studying a state whose minority students score a grade level higher than your statewide average on reading.