“A sharp distinction must always be made between the physical survival of particular schools and the survival of the educational quality in those schools.”

“A sharp distinction must always be made between the physical survival of particular schools and the survival of the educational quality in those schools.”

So writes American economist and social theorist Thomas Sowell in his latest book, Charter Schools and Their Enemies. If we measure analysis by its predictive abilities — anticipating problems that will recur when demonstrably successful ideas are ignored — Sowell’s book is nothing short of prophetic.

Consider: The American Federation of Teachers’ announced at the end of July that it would support a local chapter’s decision to go on strike “as a last resort” if schools opened with “unsafe school reopening plans.” These qualifying phrases seem to have been included for rhetorical purposes only.

Just days after the announcement, union members across the country, from Los Angeles to Baltimore, held protests, even though these and other large school districts are not opening in-person. (Florida’s constitution and state law prohibit teachers and other public employees from striking; however, the Florida Education Association recently won a lawsuit against the state over an order mandating the reopening of all public school campuses. The state has appealed.)

Last week, Detroit’s union (an affiliate of the AFT) voted in favor of a strike if policymakers changed the district’s current policy of offering classes online only.

Sowell predicted unions were capable of as much, writing, “Since teacher unions have millions of members and spend millions of dollars on political campaigns, they do not need logic or evidence to gain the support of elected officials who need campaign contributions to finance their re-election campaigns.”

Political action, not improved student learning, is behind union activity. The union chapters behind the “National Day of Resistance” on Aug. 3 that followed the AFT’s announcement posted an agenda that included calls for “police-free schools,” “canceling rents and mortgages,” and “providing direct cash assistance to those not able to work or who are unemployed,” along with a “massive infusion of federal money.”

Here, again, Sowell proved prescient. As he noted in his book, teacher unions embrace a slew of policies for which “there are usually no educational benefits to students.” Where does a child’s education fall on their list of priorities? As Sowell observes, “The plain and direct question that must be asked, again and again, is: ‘How, specifically, is this going to make the education of children better?’”

As Sowell notes, such interest groups are “enduring institutions with enduring personnel” that “maintain a given set of policies and practices over time.” This was evident last year, when teacher-union members in West Virginia refused to work until state lawmakers stopped considering a proposal to create private learning opportunities for children with special needs. Unions in Kentucky did the same. Strikes are nothing new, but unlike previous year’s strikes in Oklahoma, Arizona, West Virginia and elsewhere, these 2019 job actions were not centered on pay and working conditions. These strikes were efforts to drive policy by force.

Re-opening schools is a local concern. State agencies and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control can offer useful information and guidance, but in the end, the decision on how public schools will operate — be it with virtual, hybrid, or in-person instruction — should be left to members of a community, including parents, educators, and health officials. In making these decisions, the question foremost in their minds should be Sowell’s: How will this make the education of our children better?

Parents and educators are not waiting for union demands to be met — nor should they. As some school districts such as Chicago, Houston, Atlanta, and more announce they will offer only virtual instruction to start the new school year, parents are enrolling their children elsewhere (Detroit private schools are reporting waiting lists), choosing to homeschool or organizing neighborhood “pandemic pods” alongside teachers.

Families and policymakers alike should tire of teacher unions’ attempts to maintain power when parents choose an option outside of a child’s assigned school. Union demonstrations garner headlines and try to browbeat school officials to give them what they want. But recent activities, with their laundry list of assorted policy demands, reveal these special interest groups to be more interested in political opportunism than providing the best possible education for students.

Most Florida schools, awaiting a decision in the case, already have returned to face-to-face instruction.

Renzo Downey, Florida Politics

A Leon County court has sided with Florida’s teachers union over the state’s order for schools to reopen amid the COVID-19 pandemic, issuing a temporary hold on that order.

Leon County Circuit Judge Charles Dodson found that Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran‘s order requires schools to reopen to receive funding. That “essentially ignored the requirement of school safety.”

Earlier this month, the Florida Education Association requested a temporary injunction “to stop the reopening of schools until it is safe to do so.” The union, NAACP and others filed the lawsuit against Gov. Ron DeSantis, Corcoran and Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos Giménez.

The order would deny funding to districts that remain closed over concerns for public health, which is constitutionally protected, Dodson said.

“There is not room in many classrooms for social distancing,” Dodson wrote. “There is not room to put desks 4 feet apart, much less 6 feet apart as is recommended. Students entering and leaving classrooms are inherently close together.”

Additionally, not all students might wear masks, teachers don’t have adequate personal protective equipment and teachers are asked to sanitize their own classrooms between classes.

Districts could delay the school year if it means making classrooms safer, DeSantis has said. But “the districts have no meaningful alternative” to reopening if they want to keep their funding, Dodson wrote.

DeSantis and Corcoran have also said any teacher could opt out of in-person teaching. Teachers working from home could teach remote learning classes, DeSantis offered.

“But that option is not being provided to all teachers,” Dodson wrote. “Some teachers are being forced to quit their profession in order to avoid an unsafe teaching environment.”

Department of Education officials denied both Hillsborough and Monroe county school districts’ plans to delay reopening while it permitted Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties’ districts’ delayed plans. The difference was that the three hotspot counties are still under Phase 1, but the order didn’t distinguish between Phase 1 and Phase 2 counties.

However, Dodson did not throw out the complete order. Removing the requirement for “brick and mortar” classes, among other changes, would make the order constitutional in his eyes.

Several uncertainties remain about COVID-19, including to what extent children can infect adults, Dodson said. But DeSantis has pointed to studies that show low rates of transmission between children and adults as evidence that it is safe for classrooms to open.

“What has been clearly established is there is no easy decision and opening schools will most likely increase COVID-19 cases in Florida,” Dodson wrote.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jude Schwalbach, a research assistant at The Heritage Foundation, first published on The Daily Signal.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jude Schwalbach, a research assistant at The Heritage Foundation, first published on The Daily Signal.

When COVID-19 brought the school year to an abrupt halt early this year, few anticipated that the global pandemic would be the impetus for private school choice reforms across the nation.

As is the case with so many other sectors, many private schools struggled after losing tuition and other funding resources due to the strains of COVID-19.

In fact, the Cato Institute reported that as of this month, 115 private schools had announced permanent closures.

That means that more than 15,400 children lost their schools. The estimated transfer cost of these students to public schools is more than $278.3 million.

Recognizing what the loss of education options would mean for families, policymakers in six states proposed emergency private school scholarships in response to the crisis. Four of those states—Florida, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and South Carolina—used emergency federal funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to expand private school choice options.

The CARES Act, signed into law by Donald Trump in June, authorized $3 billion for the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund, or GEER, a flexible grant that governors can use for education-related programs.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, used a portion of his state’s GEER funds to craft “Stay in School” scholarships, providing $10 million to cover tuition at Oklahoma’s 150 private schools for children from low-income families whose incomes have been affected by the coronavirus pandemic. More than 1,500 Oklahoma children could receive a scholarship worth $6,500 each.

That covers all or most of the average annual cost of private school tuition in Oklahoma, which is about $5,000 for elementary students and about $7,000 for secondary students. The scholarship amount, however, is still less than the average per-pupil amount, $8,778, spent annually by Oklahoma public schools.

Oklahoma students also will have access to the $8 million Bridge the Gap Digital Wallet education savings account-style funding, which is funded by GEER and will provide more than 5,000 children living in poverty with $1,500 grants to “purchase curriculum content, tutoring services and/or technology.”

In the era of pandemic pods, this is critical policy.

Likewise, South Carolina used its GEER funds to create a private school scholarship program for children from low- and middle-income families. Children living at or below 300% of the federal poverty line could be awarded a scholarship of about $6,500.

Other states used these funds to bolster existing private school choice programs such as tax credit scholarships.

New Hampshire under Gov. Chris Sununu, a Republican, boosted funding for the state’s tax credit scholarship by $1.5 million. The state’s tax credit scholarship allows individuals and businesses to receive tax credits for donating to nonprofits that fund private school scholarships.

Since 2015, New Hampshire’s tax credit scholarship has allocated $3.8 million to help 1,377 children attend private schools of their choice. The additional emergency funds will help 800 children receive scholarships valued at $1,875 each. That amount covers more than 22% of the average cost of tuition at a private elementary school in the state.

Like New Hampshire, Florida used $30 million of its GEER funds to stabilize its tax credit scholarship. At the same time, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, also put $15 million toward the Private School Stabilization Grant Fund. Private schools are eligible for this grant if they were hard hit by the pandemic and if more than 50% of the student body uses school choice scholarships.

Never missing a beat, special interest groups have alleged that efforts in those states to use GEER funds to support families accessing education options of choice will hurt public schools. Yet, public schools in Florida, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and South Carolina received a combined $1.1 billion from the CARES Act. Of that, the total governors’ discretionary funds accessible to children enrolled in private schools in the respective states totaled $96.5 million.

Taxpayers and state policymakers are right to balk at the new federal education funding. The $13.5 billion CARES Act, along with the $3 billion in GEER funding, is significant new federal spending, representing more than 25% of what the federal government spends yearly on K-12 education through the Department of Education’s discretionary budget.

But as The Heritage Foundation’s Jonathan Butcher wrote: “If the funds already are appropriated for education, as it is with CARES spending, then there is no more effective purpose than to give every child a chance at the American dream with more learning options.”

Moving forward, state policymakers should make sure that the emergency private school scholarships become permanent, funding them through changes to state policy. Rethinking how education funding is delivered, through more nimble models such as education savings accounts, should remain a permanent feature of the education policy landscape.

Moves in these states are steps in the right direction.

Hedge fund analyst Sal Khan began making math tutorials for his cousins in 2004. By 2016, Khan Academy had more than 42 million registered users from 190 countries with tutorials on math, economics, art history, health, computer science and more.

Last week, Lindsey Burke authored an interesting piece for redefinED titled, “Do pandemic pods represent disruptive technology?” A different question could be: Do pods represent the incremental improvement to digital learning that will bring that type of learning into disruptive territory?

Typically, a disruptive technology starts as what is perceived to be an inferior but more accessible product or service “competing against non-consumption.” A classic example from the early computer era featured mainframe computers as the dominant technology and personal computers as the disruptive technology. Early personal computers weren’t great, but access to mainframe computers was a very scarce commodity. Thus, personal computers were better than nothing.

The key comes with the flip: Personal computers got better over time, and at some point, people realized they were just as good or better than mainframe access. Personal computers displaced mainframe computers as the dominant technology.

Rather than thinking of pandemic pods as a disruptive technology, they may fit in the disruption model better as the incremental improvement to digital learning. Digital learning, in other words, may have been advancing in a “pre-flip” disruptive technology until innovators improved it sufficiently for many people to see it as a better form of learning.

Digital learning often competes against non-consumption by serving students who, for a variety of reasons, would otherwise drop out of school. It serves other student niches as well. Most people, however, view education as an inherently social activity – with classmates, group activities and in-person instruction. Pods can scratch all these itches in ways that purely digital learning will struggle to do.

It is too early to know much about the combination of digital learning and pods in terms of academic outcomes. It is obvious walking in the door of a school taking advantage of both that the teachers and students are having fun, a quality often lacking in large, impersonal schools. As I discussed in a recent column, I had the opportunity to observe at group of students engaged in 3-D printing at a Prenda micro-school on the Apache Nation in San Carlos, Arizona. The thought that would not leave my head was, “Scout troop meets Sal Khan = fun school model!”

The very impressive digital learning techniques developed by Success Academy, for instance, could have a significant staying power after the pandemic. We see hints of South Korean super-star instructors in dividing teachers into digital lecturers and small group leaders. Nothing screams “impersonal” louder than a district (NYC) which numbers rather than names its schools, and the digital version of Success Academy could be offered to waitlisted students.

If, however, Success Academy organized students into pods and enrolled them in its distance learning program, something truly disruptive could emerge. The pod leader would take on the role of the small group leader in this scenario, leading discussions and facilitating group projects in scout troop leader fashion. Digital learning would provide real-time instruction and access to Success Academy’s finest lecturers from its entire network of schools. It would not be necessary to battle Bill de Blasio to follow the laws of New York and provide space.

Pods are small enough to meet in informal spaces, and equity concerns, such as money to pay guides, provide devices and academic transparency, all could be addressed.

I suspect that combining the in-person element of pods to digital learning is something that a many families and educators will find appealing long after the pandemic has faded. Big-box schooling already was set to struggle to replace retiring Baby Boom teachers in Florida and around the country. Just guessing, but those eligible may be retiring at a faster rate given the pandemic.

A new school model that is fun and empowering to teachers just might be the solution we need, when we need it.

Editor's note: With this commentary, redefinED welcomes education policy expert Lindsey Burke, director of the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation, as our newest guest blogger.

Editor's note: With this commentary, redefinED welcomes education policy expert Lindsey Burke, director of the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation, as our newest guest blogger.

Education policy scholars, especially proponents of school choice, have long referenced the late Clayton Christensen’s work on disruptive innovation. Christensen, along with his colleague Joseph Bower, detailed the concept of disruptive innovation in the Harvard Business Review in 1995.

The idea of “disruption” in a sector “describes a process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses,” wrote Christensen, Michael Raynor, and Rory McDonald in 2015 in a follow-up Harvard Business Review article refining the theory.

Disruptive innovation theory posits that dominant incumbent businesses may ignore a segment of their consumer base as they focus on improving products for their most profitable customers. Scrappy new market entrants then target neglected customers with early, cheaper versions of their product, and then begin growing market share as the product improves. The new business then begins capturing more customers, improving product performance while maintaining affordability, and eventually becomes mainstream.

Christensen and his colleagues caution against over-application of the theory to phenomena that do not actually represent disruptive innovation, but rather sector transformation. For example, they note that Uber, despite its incredible impact on the taxicab industry, represents sector transformation rather than disruption in part because of Uber’s large market share. This is also the case because Uber wasn’t competing with the absence of a vehicle transportation market, just a crummy one.

To be appropriately described as “disruptive,” a new entrant into the market must be enabled by one of two conditions: 1) “low-end footholds” or 2) “new-market footholds.” “Low-end footholds” emerge when existing businesses ignore “less-demanding” customers because they are overly focused on their more “profitable and demanding” customers. “New-market footholds” emerge when there isn’t a market for a good or service, turning “nonconsumers into consumers.”

As Christensen and his colleagues explain, the bottom line is this: Genuine disruption happens by market entrants “appealing to low-end or unserved consumers” and then capturing the “mainstream” market.

So, does the new phenomenon of pandemic pods unfolding across the country qualify as disruptive innovation in the K-12 space?

They certainly check some of the initial boxes.

Pods are a “new-market foothold” competing with non-consumption. Pandemic pods arose this summer after the widespread school shutdowns that occurred during the spring showed no sign of stopping. Parents, concerned about the prospects for their children’s education this fall, began teaming up with other families in their neighborhoods or social circles to hire teachers for their children. Some families unenrolled their children from their district school completely, registering in their state as homeschoolers and then joining a pod.

With pods, families work together to recruit teachers that they pay out-of-pocket to teach small groups — “pods” — of children. It’s a way for clusters of students to receive professional instruction for several hours each day. Families pool resources to pay tutors who may serve as a full-time teacher for the pod of students or may only teach on a part-time basis.

With many school districts around the country planning not to reopen classrooms this fall — or, at best, planning to offer some combination of virtual and in-class instruction — pods are competing with non-consumption, establishing themselves through a “new-market foothold.”

But time will tell whether pods remain a permanent facet of the education landscape. Disruptive innovation theory also holds that “innovations don’t catch on with mainstream customers until quality catches up to their standards.” Rather than making improvements to existing products in a market (such as increasing the computing power of a laptop or the cooking consistency of a microwave), disruptive innovations are “initially considered inferior by most of the incumbent’s customers.”

So, here’s where the ground is a little shakier for pods as a disruptive innovation. According to Christensen’s work on the subject, disruption also has a second qualifying condition: The new product must be inferior to the product offered by the incumbent.

Parents may consider some, but not all, of the components of a pod inferior to the existing education model. They may find the academics to be more rigorous, but the custodial component less competitive if it doesn’t provide the same length of coverage. Pods also are on shakier ground vis-à-vis disruption because some families join as a supplement to the crisis online instruction their children are still receiving through their district school. In that way, they could end up complementing the incumbent rather than disrupting it.

A third marker of disruption: The eventual improvement of quality. But there are already promising developments in the realm of pod quality. Education researcher and redefinED executive editor Matthew Ladner describes what a marriage between pods and established charter incumbents like Success Academy could entail. As Ladner explains, taking the Success Academy (COVID-era) model of "most skilled math instructor in the network [giving] live internet broadcast lectures" and coupling that with teachers and tutors working in small pods across the country to assess student learning and provide individual instruction could lead to high-quality pods at scale.

Finally, to truly qualify as a disruption, pods also will have to eventually serve a broad segment of the K-12 market. This will only happen through policy changes that can enable widespread participation in the model on the part of lower-income consumers.

For parents who cannot afford to pay out-of-pocket to contribute to a neighborhood pod, providing resources through education savings accounts (ESAs) will be a crucial support moving forward. With an ESA, currently available in Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee, and North Carolina, eligible families whose children exit the public education system can receive approximately 90% of what the state would have spent on that child in her public school directly into their ESA. These restricted-use, parent-controlled accounts can then be used to pay for any education-related service, product, or provider of choice, including private school tuition, special education services and therapies, online learning, and private tutors.

Unused funds can even be rolled over from year to year. They enable families to completely customize their child’s education and are the perfect education financing policy to support families of all economic levels enrolling their children in pods. The pandemic has made it clearer than ever that every state needs to provide education choice – ideally through an ESA model – to all children, yesterday.

Universal ESAs would enable pods to serve a broad segment of the K-12 market, competing with, and potentially disrupting, the district school model.

Currently, district schools are mostly closed to in-person instruction, creating a clear case of non-consumption with which pods can compete. But even when the public education “product” is on the market as usual, it’s not a product that is serving consumers particularly well. Just one-third of students across the country can read and do math proficiently, and in some of the largest school districts in the country, like Detroit, those figures fall into the single digits.

Just as the pandemic is reshaping so many aspects of our lives, it also is reshaping education. Although the extent to which this transformation is permanent is yet to be seen, some non-trivial percentage of families is likely to continue their children’s education in something other than a district public school even when the pandemic subsides.

Pods could be what they choose. Pods are a “new-market foothold” that are competing with non-consumption (closed public schools), and could, at present, be considered an “inferior” product. But that will change as families and service providers refine the pod product. At that point, coupled with changes to policy providing ESAs to as many students as possible, they could fundamentally change the education marketplace.

As such, pods are a strong contender for what could be disruptive innovation in the K-12 space.

Stephanie Conner uses a Florida education savings account for students with special needs to provide a combination of educational services -- therapy, homeschool, private school -- for her son Eli, foreground. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

State and local officials in Florida are discussing how to best regulate parents who are facilitating learning pods, homeschooling cooperatives and micro-schools that satisfy Florida’s mandatory school attendance law. For the last 175 years, the distinction between parents and public-school teachers was clear. But COVID-19 has muddied the waters.

In the last six months, public and private schooling has merged with homeschooling, with parents doing much of the teaching. As schools open this fall, parents will continue to be the primary schoolteacher for millions of K-12 students. How should state and local governments regulate these parent teachers?

Let’s start with the unprecedented unbundling of education services. Instead of getting all their services from a single provider — their assigned neighborhood school — parents are increasingly accessing education services from multiple providers. The unbundling of childcare from academic instruction is the best example. For the first time in at least 150 years, most students will not receive their childcare services from their academic instructional provider this fall. Many parents are providing childcare at home while their students receive online instruction. Other parents are paying Boys and Girls Clubs, YMCAs, municipal community centers and other parents to provide childcare.

Many of these childcare providers are also providing education support services, such as in-person tutoring that complements online instruction. This is especially true when the online instruction is asynchronous. These latter situations provide state and local regulators with interesting challenges, because these childcare providers are also teaching.

Florida state law regulating private school employees serving scholarship students requires “each employee and contracted personnel with direct student contact, upon employment or engagement to provide services, to undergo a state and national background screening … An ‘employee or contracted personnel with direct student contact’ means any employee or contracted personnel who has unsupervised access to a scholarship student for whom the private school is responsible.”

This background check requirement makes sense for any childcare provider who is supervising children from multiple families. A parent who is leading a 10-student homeschool cooperative or micro-school should be required to pass a background screening.

Private school teachers are not required to have a state teaching certificate. This also seems appropriate for homeschool cooperative and micro-school parent teachers.

Whether a homeschool cooperative or a micro-school is receiving public funding should have no impact on how the parent teachers are regulated. All instruction that is satisfying a state’s mandatory attendance laws should be held to a same standard — background checks but no certification requirements.

We will never go back to the pre-pandemic public education system. Diversity, flexibility, and customization will be much bigger components of schooling moving forward. We need to quickly and thoughtfully adjust our policy infrastructure to support this new normal.

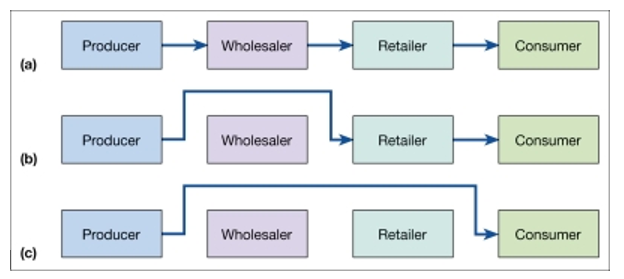

Disintermediation: (noun), the elimination of an intermediary in a transaction between two parties

Disintermediation: (noun), the elimination of an intermediary in a transaction between two parties

Those of us working in K-12 education policy should familiarize ourselves with this concept, often described as “cutting out the middleman.” Wikipedia helpfully explains:

Disintermediation initiated by consumers is often the result of high market transparency, in that buyers are aware of supply prices direct from the manufacturer. Buyers may choose to bypass the middlemen (wholesalers and retailers) to buy directly from the manufacture, and pay less. Buyers can alternatively elect to purchase from wholesalers. Often, a business-to-consumer electronic commerce (B2C) company functions as the bridge between buyer and manufacturer.

Well hello there, pandemic pods!

This trend has been going on for a long time with regard to enrichment educational activities. The pandemic has accelerated this trend into core academic instruction. If policymakers want low-income children and those with special needs to have the opportunity to participate, public policies allowing dollars to follow children will be necessary.

In the absence of such policies, already gigantic achievement gaps between the well-to-do may widen further still. The Denver school district among others recently essentially cautioned parents against forming pods expressing equity concerns. This is exactly the wrong approach. Rather, the district should be assisting interested disadvantaged families in the formation of pods of their own.

This commentary from Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, first published on the RealClear Policy blog.

This commentary from Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, first published on the RealClear Policy blog.

A new Gallup poll that surveyed parents with school-aged kids has startling results, much more because of how opinions are split than the opinions themselves.

Given the COVID-19 threat, 36% of parents want their children to receive fully in-person education, 36% want an in-person/distance hybrid, and 28% want all distance. Each mode was preferred by essentially one-third of parents, neatly capturing a now undeniable reality: Families need school choice.

The basic problem is that diverse people have different needs, but a school district is unitary. This is always trouble — diverse people are stuck with one dress code, history curriculum, etc. — but COVID-19 makes the stakes far higher and more immediate than usual. You might be willing to engage in a protracted school board battle to improve curricula, but COVID-19 could put your child’s life, or basic education, in potentially huge danger right now.

In many places, the public schools have taken the side of maximum COVID caution. The school districts in Los Angeles, Chicago, and elsewhere will, at least to start the year, only offer distance education.

That may be fine for kids who learn better at home, have medical conditions that make them high-risk, or who live with elderly relatives. But it is a huge hit to children with poor internet connectivity, learning disabilities, or those who simply thrive in a physical classroom.

It appears that a spontaneous, nationwide eruption of parent-driven, in-person education is the response to such closings. The “pod” phenomenon is perhaps the most buzzy sign of this, generating both fascinated and skeptical coverage in major media outlets. Basically, parents are pooling their money to hire teachers and create closed learning communities for their kids.

We may also be seeing more families moving to traditional private schools, with reports of privates receiving increased interest, and sometimes definite enrollment boosts, around the country. There is no systematic data to confirm a national movement, but the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom has been tracking private school closures connected to COVID-19 since March and has only recorded eight since July 14. This low number may well reflect new enrollments in private schools.

Of course, affording a private alternative can be difficult for lower-income families, and many people worry that the move to private schooling will fuel greater inequality.

Thankfully, there is a solution, and it is straightforward: Instead of education funding going directly to public schools, let it follow children, whether to a pod, private school, charter school, or traditional public. With public school spending exceeding $15,000 per student, most privates, which charge roughly $12,000 on average, would be in anyone’s reach, while families pooling 10 kids could offer $150,000 to a pod teacher.

The Trump administration has been pushing choice, and certainly any federal aid should follow kids. But constitutional authority over education lies with the states, and it is from them that choice should come. Indeed, more than half-a-million children already attend private schools through voucher, tax credit, and education savings account programs in 29 states and Washington, D.C. But that is far below the number who need choice — states that already have it should expand it, and those without it should enact it.

But expanding funding may not be enough to supply the COVID choice people need. In some places, including much of California, public authorities are forbidding many private institutions from teaching in-person. Such prohibitions must be lifted.

These actions may be intended to protect public schools’ pocketbooks. For instance, the chief health official in Montgomery County, Maryland, has said no private school can open until at least October 1, a date right after the enrollment “count day” that determines how much state and federal funding public schools get.

Of course, health concerns may be the only driver of such decisions. But school-aged children appear to face very low levels of COVID danger. According to CDC data, Americans ages 5 to 17 account for fewer than 0.1% of all COVID-19 deaths, and since tracking began, it has accounted for less than 1% of all deaths in the 5-to-14 age group. While increasing safety measures is important, kids appear to face greater dangers than COVID-19.

What about teachers and administrators? Adults are at greater risk than children, but private schools will do many things to protect them, including mandatory mask wearing, face shields, social distancing, improved air filtration, and more. And teachers unwilling or unable to work in-person could choose jobs in online-only schools.

The simple fact is all communities, families, and children are different, and they need educational options reflective of that diversity.

The House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis on Aug. 6 held a public hearing on “Challenges to Safely Reopening American Schools,” featuring former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan; Caitlin Rivers, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; Broward County (Florida) Public Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie; and Angela Skillings, a second-grade teacher in the Hayden-Winkelman Unified School District in Arizona. You can see their prepared testimony here, here, here and here. redefinED guest blogger Dan Lips, a visiting fellow with the Foundation for Research and Equal Opportunity, also participated. The following is Lips’ condensed spoken testimony.

The House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis on Aug. 6 held a public hearing on “Challenges to Safely Reopening American Schools,” featuring former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan; Caitlin Rivers, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; Broward County (Florida) Public Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie; and Angela Skillings, a second-grade teacher in the Hayden-Winkelman Unified School District in Arizona. You can see their prepared testimony here, here, here and here. redefinED guest blogger Dan Lips, a visiting fellow with the Foundation for Research and Equal Opportunity, also participated. The following is Lips’ condensed spoken testimony.

As we have heard today, communities across the country are facing a difficult decision about how to begin the school year during the pandemic. The prospect of any child, teacher, or school employee contracting COVID-19 and facing the possibility of death or serious illness should weigh heavily on all policymakers involved with decisions affecting schools’ plans.

But it is critical that policymakers also recognize the serious risks associated with prolonged school closures, particularly for disadvantaged children.

Researchers studying the educational effects of school closures warn that time out of school results in months of lost learning, and that the learning losses are most acute for low-income students.

The bottom line is that prolonged school closures will create a large achievement gap for a generation of American children. Beyond these educational effects, prolonged school closures create significant risks for children’s health and welfare.

There is alarming evidence, which I describe in my written testimony, that prolonged school closures since the spring have endangered child welfare. Closures also have significant negative economic effects for parents. Many parents have been forced to choose between their jobs and their child’s care, and this challenge is most difficult for single parents.

The good news is that it is possible for schools to reopen.

Health experts — including the American Academy of Pediatrics — have issued guidelines for safely reopening schools with certain precautions, such as physical distancing, utilizing outdoor space, cohort classes to minimize crossover among children and adults, and face coverings for students (particularly older students).

And we are seeing many school districts choose to reopen across the country with in-person instruction or hybrid learning options.

According to a new analysis from the Center for Reinventing Public Education, 41 percent of rural districts and 28 percent of suburban districts plan to provide in-person instruction this fall. But most the nation’s largest school districts are not reopening with in-person instruction.

Seventy-one of the nation’s 120 largest school districts are beginning the school year with remote instruction and no in-person learning, based on FREOPP’s review. Altogether, these closed school districts serve more than 7 million children — including 1.4 million children living in poverty.

It is important to recognize that children from low-income families have fewer resources to learn outside of school than their peers. According to one estimate, rich families spend more than $9,000 out of pocket on their children’s educational and enrichment outside of school, while the poorest families spent just $1,400.

Today, families with financial means are working to create better options than remote learning — including homeschooling and setting up “pandemic learning pods” by forming coops with other parents and hiring teachers or tutors. But children from lower-income families have few options. Policymakers must address this inequality.

For example, states should use existing CARES Act funds to provide aid directly to parents in the form of education savings accounts or scholarships to support their children’s outside of school learning needs. Oklahoma, New Hampshire, and South Carolina are already doing this. Other states should follow their lead.

As Congress considers future aid packages for K-12 education, you should provide aid directly to parents to help disadvantaged children learn when their school is closed. There is precedent for providing emergency education relief in this manner.

After Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita in 2005, many children were displaced and had nowhere to go to school. Congress provided more than $1 billion in aid that followed affected children to a school of their parents’ choice, allowing them to continue their education.

If millions of children are unable to attend school this year, Congress should focus much of its aid in a similar manner — providing direct assistance to help children continue learning while schools are closed. In my written testimony, I discuss these and other recommendations for how school systems can prioritize and address the needs of disadvantaged children during the pandemic.

Since 1965, Congress has rightly focused federal education aid on promoting equal opportunity for at-risk children. In 2020, this will require focusing aid to support disadvantaged kids who can’t go to school.

The Foundation for Research and Equal Opportunity will host an executive briefing on its recommendations for reopening and continuing American education during the pandemic on Thursday. Visit https://freopp.org/ for details.

Keys Gate Charter School in Homestead, Florida, is one of several campuses managed by Charter Schools USA that will begin the academic year with distance-learning only.

One of the largest public charter school operators in Florida has revisited a decision to open its brick-and-mortar locations for the coming school year, citing concerns over a spike in COVID positivity in some counties it serves.

Charter Schools USA, which operates 92 schools in five states, had informed families it would physically open all 14 of its South Florida schools. Last week, officials announced that the Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade County campuses would offer a “fully mobile classroom experience” instead.

Those schools will equip classrooms with voice-activated camera technology that will follow teachers around empty classrooms. Students will have a full view of the room as well as any materials a teacher wants them to see.

Officials say they will keep a close eye on COVID data and will have all 18,000 Charter Schools USA students back to in-person education as soon as possible. Teachers with health and safety concerns who are still hesitant to return to the classroom will have the option of teaching remotely.

In the meantime, the two CSUSA schools in St. Lucie County will offer three options: in-person instruction, fully mobile classrooms and a combination of in-person and mobile learning.