DAVENPORT, Fla. – Valeria Oquendo didn’t set out to be an entrepreneur. “Ms. V,” as her students call her, had wanted to be a teacher since she was a teenager. On her way to an elementary education degree, she interned at a public school and, initially, those dreams became even clearer.

“Still in my brain I was thinking, ‘I’m going to graduate, I’m going to have my perfect classroom, I’m going to be a first grade teacher,’ “she said.

But then, in education-choice-rich Florida, a funny thing happened.

Oquendo’s “side hustle” became her full-time gig.

When COVID-19 hit in 2020, friends and family begged Oquendo to tutor their children, many of whom were struggling with online instruction. Oquendo was still in college. But before she knew it, she was tutoring 20 kids.

The light bulb flickered on.

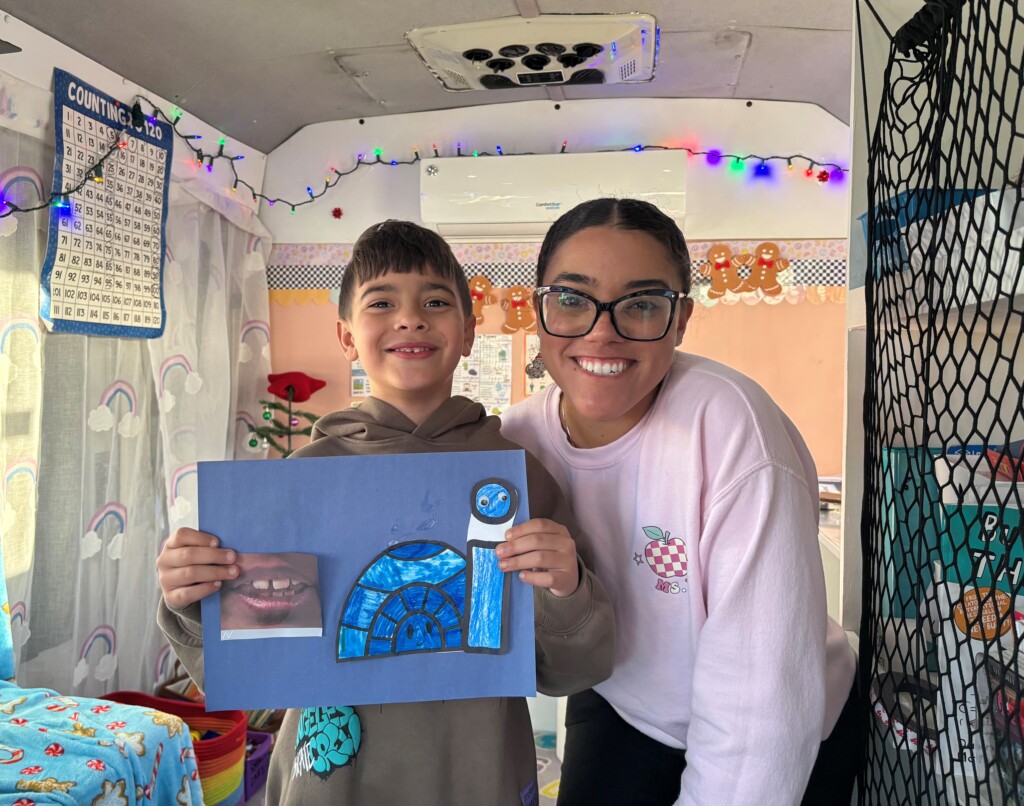

Today, Oquendo runs Start Bright Tutoring, a mobile tutor and a la carte education provider in this insanely fast-growing corner of metro Orlando.

She focuses on elementary reading and math, with 20 to 30 students who are homeschooled or in public schools. A handful use state-supported education savings accounts (ESAs), and it’s highly likely even more will use them in the future.

Demand is soaring. When Oquendo pitched her business on TikTok, mayhem ensued: She racked up hundreds of thousands of views and put 70 students on a wait list before being forced to stop taking calls.

Now Oquendo sees a future outside of traditional schools not only for herself, but for other young educators. As choice continues to expand, she said, more and more can tap into the new possibilities.

“Everybody has their niche,” said Oquendo, 26. “It all depends on the effort and not giving up.”

Florida is humming with former public school teachers who, thanks to choice, have created their own learning models. Their often-inspiring stories (like this and this and this) are becoming commonplace.

Oquendo, though, is the next wave: Educators creating their own options instead of becoming traditional public school teachers.

Oquendo represents a couple of other fascinating trend lines, too.

She’s a niche provider instead of a school, which allows her to serve Florida’s fastest-growing choice contingent: a la carte learners.

Florida has multiple ESA programs that give families flexibility to pursue options beyond schools. With ESAs, they can choose from an ever-growing menu of providers, like Start Bright, to assemble the program they want. The main vehicle for doing that, the Personalized Education Program scholarship, met its state cap of 60,000 students this year, up from 20,000 last year.

Oquendo’s decision to create an option on wheels is also noteworthy.

Florida’s education landscape gets more diverse and dynamic every day. But it’s still rife with frustrating stories about talented teachers trying to set up microschools and other innovative models, only to run into outdated zoning and building codes and/or code enforcers who seem to be curiously inflexible. (Thankfully, some still find happy endings.)

Until those barriers are addressed, going mobile – something choice visionaries suggested nearly 50 years ago – may be one way out.

Oquendo is the daughter of a police officer and an accountant. After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, the family moved to Florida, and she enrolled in the University of Central Florida.

Oquendo said she was fortunate to have an amazing teacher as her mentor when she interned at a public school. But she was also haunted by the moment the teacher told her the class needed to move on to the next unit of study, even though several students, including one with a learning disability and another learning English, were not ready.

“She said, ‘This is what we do.’ “Translation: We have to move on.

That experience pushed Oquendo to choose a different path, too.

Initially she wanted to steer her tutoring venture into a microschool. She found a good location, but the building needed $15,000 in adjustments to meet building codes, and even then, there was no guarantee of a green light from local officials. Oquendo was bummed. Thankfully, her mom came to the rescue, inspired by a mobile grooming service the family uses for its Schnauzers.

“She said, ‘Why don’t you get a van and make it a mobile classroom?” Oquendo said. “I was like, ‘Mom, the kids are not pets.’ “

Upon further investigation, mom was on to something. In the summer of 2021, Oquendo spent $8,000 for a 2014 Ford E-350 shuttle bus, then another $7,000 to turn it into a mini-classroom. Ms. V’s van is complete with desks, bins, lights, shelves, computers – and just about anything else you’d find in a typical classroom.

That fall, Oquendo was up and running, visiting students in their homes. At some point, she realized she could reach more families if she parked at locations that were still convenient – like shopping plazas – and have them meet her there.

Oquendo’s TikToks came just months after she earned her degree. The response was understandable, she said, given that many families lived the same reality she witnessed as an intern.

“It’s the system,” she said. “If it was better, we wouldn’t have the demand.”

Oquendo said many families also respond to her because they share a cultural connection. She was still struggling with English when her family moved to Florida, and many of her students are English language learners, too. She offers living proof they will overcome.

“I tell them, ‘I get you,’ “she said. “I tell them, ‘It’s okay to make mistakes. I love mistakes.’ That way, they’re not afraid.”

Forging her own path has not been all peaches and cream.

At one point, the van engine died, and Oquendo had to find $6,000 to replace it. At another, she invested in solar panels, hoping to cut down on fuel costs for air conditioning. But they didn’t work as she hoped. “I didn’t have a guide,” she said. “I just had myself – and my mistakes.”

At the same time, she said, she takes satisfaction in knowing her students are making progress. And that she has the power to quickly adjust, both for them and herself.

Oquendo is shifting to serve more students whose parents want in-home tutoring for longer stretches. She’s adding Spanish lessons. She’s also offering monthly field trips to places like LEGOLAND and a local farm.

On a whim, Oquendo recently set up gardening lessons for interested families, essentially sub-contracting with an organic farmer. Her students loved it.

In South Florida, similar operators are realizing they fit into changing definitions of teaching and learning and becoming ESA providers themselves.

Oquendo said the challenges to doing her own thing are real. But the freedom to control her own destiny, and to better help students in the process, makes it all worth it.

“I feel happy, blessed, and fortunate to be doing what I love the most,” she said.

The story: Students with disabilities and English language learners were poorly served before the pandemic and will need urgent, long-term help to recover from learning losses, according to a report from the Center for Reinventing Public Education.

The Arizona State University think tank released its annual State of the American Student report today, with a bit of good news but mostly bad news.

“Our bottom line is we’re more worried at this point than we thought,” said Robin Lake, the center’s executive director. “COVID may have left an indelible mark if we don’t shift course.”

The good: Students are bouncing back in some areas. The average student has recovered about a third of their pandemic-era learning losses in math and a quarter in reading.

States and districts nationwide have implemented measures like tutoring, high-quality curricula, and extended learning time, and more school systems are making these strategies permanent. Florida, which offers the New Worlds Scholarship for district students struggling in reading and math, is on a list of states lauded for providing state-funding for parent-directed tutoring.

Rigorous evaluations confirm the effectiveness of tutoring at helping students catch up.

Rigorous evaluations confirm the effectiveness of tutoring at helping students catch up.

Education systems across the country – as well as students and families – are starting to recognize the value of flexibility. “As a result, more new, agile, and future-oriented schooling models are appearing.”

That includes microschools and other unconventional learning environments, which are multiplying to meet increasing parent demand.

The bad: These proven strategies aren’t reaching everyone. The recovery is slow and uneven. Younger students are still falling behind. Achievement gaps are also widening with lower-income districts reporting slower recoveries. And the positive studies that show tutoring’s massive boosts to student learning tended to operate on a small scale. Making high-quality academic recovery accessible to every student remains an unmet challenge.

Districts face “gale-force headwinds,” including low teacher morale, student mental health issues, chronic absenteeism, and declining enrollment.

The ugly: The report singled out services to vulnerable student populations for a special warning. The report said this group, poorly served before the first COVID-19 infection, suffered the most. Evidence can be found in skyrocketing absentee rates and academic declines for English language learners.

Special education referrals also reached an all-time high, with 7.5 million receiving services in 2022-23. The report attributed some of this to the pandemic’s effects on young children, especially those in kindergarten who were babies at the pandemic’s onset, but other factors, such as improved identification techniques and reduced social stigma around disability, are also at play.

In short, school systems face larger numbers of students requiring individualized support than ever before.

‘Heart-wrenching struggles’: While some families adapted well, most parents reported difficulty getting services for their children with unique needs. Schools were often insufficient in their outreach. Even the most proactive parents reported difficulty reaching school staff, the report said. Parents who were not native English speakers also had the additional burden of trying to teach in a language they were still learning.

“Many families said schools didn’t communicate often or well enough, and many parents felt blindsided when they found out just how far behind their child had fallen,” the report said.

Recommended fixes: Schools should improve parent communication. The report called for schools to “tear down the walls” by adding schedule flexibility to ensure students’ special education services don’t conflict with tutoring and adding more individual tutoring and small-group sessions. It said schools should also seek help from all available sources, including state leaders, advocates and philanthropists. Schools should also prioritize programs such as apprenticeships and dual enrollment to prepare students for life after graduation.

How policymakers can help: The report urged policymakers to gather deeper data on vulnerable populations so problems can be identified and corrected; provide parents with more accurate information about their children’s progress and offer state leaders a clearer picture of whether those furthest behind are making the progress they need, and help teachers use AI and other tech tools to engage students with unique needs.

The report urged policymakers to place more control in the hands of families by making them aware of their right to compensatory instruction or therapies for time missed during school closures. It also advocated offering parents the ability to choose their tutors at district expense.

The bottom line: Urgent efforts to improve education for students with exceptional needs will benefit all students, the report said. “There can be no excuse for failing to adopt them on a large scale. National, state, and local leadership must step up, provide targeted support, and hold institutions accountable.”

Public education is in the early stages of transitioning from its second to third paradigm.

In his 1962 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn described an organization’s paradigm as the lens through which the organization’s members perceive, understand, implement, and evaluate their work. A paradigm includes a set of assumptions and associated methodologies that guide a community’s determination of what is right and wrong and true and false.

A paradigm shift occurs when anomalies begin to occur, and some community members begin to question the veracity and effectiveness of their paradigm. Eventually, a few community members begin proposing new ways of understanding and implementing their work, and a prolonged contest emerges between the existing paradigm and proposed new paradigms. If a majority of the community ultimately decides a new paradigm enables them to be more successful, a paradigm shift occurs, and this new paradigm is adopted. In scientific communities, Kuhn calls these paradigm shifts scientific revolutions.

Paradigm shifts are disruptive because they require community members to reinterpret all previous work and adopt new ways of conducting and evaluating future work. Senior community members most strongly resist changing paradigms because their status comes from their application of the existing paradigm over many years. Consequently, paradigm changes are rare and require several decades to complete.

While Kuhn’s work focused on the role of paradigms in scientific communities, his description of how paradigms function and change is relevant for most organizations and communities, including public education.

Public education’s first paradigm shift occurred in the 1800s. The United States was a sparsely populated rural agrarian society in the 1700s and early 1800s, and public education was highly decentralized. Most children were homeschooled, and literacy focused primarily on reading the Bible. Religious organizations provided most of the structured instruction outside the home.

Public education’s paradigm during this period emphasized decentralization, family control, flexibility, basic literacy, and religious instruction.

This paradigm began failing as innovations in transportation and communications in the early 1800s started to connect the country and promote more industrialization and urbanization. About 90% of Americans lived on farms in 1800; 65% in 1850, and 38% in 1900. This transition from rural to urban created child care needs, and increased industrialization necessitated more people becoming more literate.

The influx of European immigrants in the early 1800s, most of whom were Catholic, caused Protestant-controlled state and local governments to see public schools as the best way to ensure newly arriving Catholic children would be properly assimilated and turned into good Protestants. However, this first paradigm was ill-equipped to address this concern.

By the early-to-mid 1800s, a consensus was forming that a new way of conceptualizing, organizing, and implementing public education (i.e., a new paradigm) was needed. First, a desire for greater centralized management and standardized instruction and curriculum led states to begin creating school districts to own and manage local public schools.

Next was the passing of mandatory school attendance laws. Massachusetts passed the nation’s first modern mandatory school attendance law in 1852 to help assimilate a growing influx of immigrants from Ireland and other predominantly Catholic countries. By 1900, 31 states had followed suit. Eventually, every state joined them, with Mississippi being the last to do so in 1918.

Mandatory attendance laws significantly increased school attendance, which created management challenges for school districts, especially in growing, urban communities. To address this surge in student attendance, school districts began adopting industrial mass production methods such as batch processing that enabled the nation’s manufacturers to produce large numbers of products with consistent quality at a lower cost.

In addition to centralizing school district management and standardizing instruction and curriculum, this new industrial model of public education replaced multi-age grouped students with age-specific grade levels which functioned like assembly line workstations that moved students annually from one grade level to the next en masse. This was the new lens through which government, educators, families, and the public were now seeing and judging public education. This was U.S. public education’s second paradigm.

Just as public education’s transition from its first to second paradigm was driven by changes in transportation, communications, and manufacturing innovations in the 1800s, the rise of digital networks, mobile computing, and artificial intelligence in the 21st century is generating changes that are causing discontent with public education’s second paradigm.

Decentralization and customization are becoming core societal values that are transforming all aspects of people’s lives, including how we work, communicate, and consume media and entertainment. Consequently, decentralization and customization will be at the core of public education’s third paradigm.

Since public education is a government responsibility, this shift from the second to the third paradigm will impact government’s role in public education. Currently, government has a monopoly in the public education market, which undermines the market’s effectiveness and efficiency primarily because it underutilizes the market’s human capital.

In this emerging third paradigm, government will regulate the public education market but will no longer be a monopoly provider. This is like the role the government now plays in the food, housing, health care, and transportation markets. Most of the responsibility for how children are educated will shift from the government to families as families assume control over how most of their children’s public education dollars are spent.

This shift in government’s role from monopolist to regulator will require many operational changes. For example, as a public education monopoly, government holds its schools accountable for achieving performance goals. Without a government monopoly in the public education market, customers (i.e., families) will hold schools accountable for performance and change schools when they are dissatisfied.

Taxpayers also are customers in the public education market, and the government is responsible for meeting their needs through how it regulates this market. While families bear the responsibility for ensuring their children’s needs are met, government continues to be responsible for ensuring the public’s needs are met.

Kuhn’s research suggests that paradigm shifts are always long and contentious. This is particularly true for public education, given how much certain groups benefit financially and politically from the status quo. Lower-income students are the ones being most underserved by public education today and will benefit the most from public education becoming an effective and efficient market. But these students’ families have the least amount of political power.

In 1791,Thomas Paine proposed an ESA-type program for lower-income children in The Rights of Man. “Public schools do not answer the general purpose of the poor. They are chiefly in corporation towns, from which the country towns and villages are excluded; or if admitted, the distance occasions a great loss of time. Education, to be useful to the poor, should be on the spot; and the best method, I believe, to accomplish this, is to enable the parents to pay the expenses themselves.”

Paine’s recommended funding method was, “To allow for each of those children ten shillings a year for the expense of schooling, for six years each, which will give them six months schooling each year, and half a crown a year for paper and spelling books.”

More than 150 years after Paine’s proposal, Milton Friedman proposed a similar but more comprehensive plan in 1955 for making the public education market more effective and efficient. Now, almost 70 years later, we are starting to see some states adopt education choice programs similar to what Paine and Friedman suggested.

Apparently, U.S. public education is more fiercely resistant to change than the scientific communities Kuhn studied, but I am hopeful public education’s current paradigm shift will be completed within the next 30 to 40 years.

Education choice critics often assert that allowing families to choose the best learning environments for their children undermines our civic culture. They say our democracy is strengthened when children are required to attend public common schools.

The idea of public common schools originated in the early-to-mid 1800s in response to increased emigration from Europe. A surge of Irish immigration into Massachusetts led that state’s Protestant-dominated government to create the nation’s first mandatory school attendance law in 1852. Horace Mann, Massachusetts’ first secretary of education, led the campaign to teach Irish Catholic children how to be good Protestants in government-run common schools.

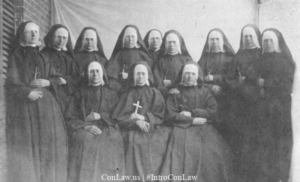

The Catholic community in Massachusetts and elsewhere rebelled against the Protestants’ public common schools and began creating Catholic schools. This ongoing conflict came to a head in Oregon in 1922 when the state amended its constitution to require all children to attend public (i.e., Protestant) common schools. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) helped lead the effort to pass this amendment.

An order of Catholic nuns sued to prevent their Catholic school from being closed and prevailed in a 1925 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Pierce v. Society of Sisters. This decision ended the public common schools movement as envisioned by Mann, the KKK, and others, but the common school myth endures.

An order of Catholic nuns sued to prevent their Catholic school from being closed and prevailed in a 1925 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Pierce v. Society of Sisters. This decision ended the public common schools movement as envisioned by Mann, the KKK, and others, but the common school myth endures.

Education choice opponents regularly assert that returning to the days of most children attending public common schools is the best way to improve our polarized civic culture. But those days never existed. Most U.S. children have never attended public common schools. For most of our history, Black and white children attended racially segregated schools. My high school was racially segregated until my junior year (1971-72), which is about 140 years after Mann helped launch the common schools movement. Neighborhood attendance zones cause public schools to be segregated by family income. Public magnet schools separate students by interests and aptitude, and academic tracking within schools segregates students by academic achievement levels.

The non-existence of mythical public common schools does not refute the criticism that education choice programs undermine our civic culture. Fortunately, a growing body of research does refute this criticism and suggests education choice programs help improve our civic culture.

Patrick Wolf is a distinguished professor at the University of Arkansas’ College of Education and Health Professions. Wolf and his research team recently reviewed 57 studies that examined the relationship between private school choice and the quality of civic engagement. These studies consistently showed that participating in private school choice is associated with higher levels of political tolerance, political knowledge, and community engagement. Wolf concluded that, “Private schooling is a boost, not a bane, to the vibrancy of our democratic republic. The benefits of private schooling in boosting political tolerance are especially vital, as we need to be able to disagree with others without being disagreeable.”

Charles Glenn is professor emeritus of educational leadership and policy studies at Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education & Human Development. Glenn conducted research that helps explain Wolf’s findings.

Glenn examined the role Islamic schools play in helping Muslim immigrant children assimilate into the U.S. culture. He found these children assimilated much better when they attended Islamic schools that help them maintain their religious and cultural identity while successfully adapting to American values and norms. Glenn concluded that these schools helped students develop a sense of belonging in both their cultural community and the wider U.S. community by focusing on cultural preservation and adaptation. This dual focus was apparently crucial to helping these Muslim children successfully integrate into U.S. society.

Glenn’s findings are similar to what we see students experiencing in the education choice programs Step Up For Students manages. Most of the students we have served over the past 23 years have come from lower-income and minority families. When we poll these families as to why they are participating in our programs, the top answer is always safety.

All people, but especially children, have a basic need to be physically and psychologically safe. Children who do not feel safe in school go into fight or flight mode, which shows up as them refusing to go to school or going to school and constantly getting into trouble.

Parents regularly report amazing transformations in their child’s behavior when they use education choice scholarships to enroll their troubled child in a school where this child feels safe. While parents often see these changes as miraculous, these improvements reflect normal human psychology. Most people’s behavior is better when they feel safe and secure.

This need for safety and security while participating in public education is why education choice programs help improve our civic culture. As Glenn’s research shows, education choice programs help families find environments in which their children learn to feel secure about who they are and learn to use this security as the basis to interact appropriately with those who are different from them.

Much of the polarization and hostility we see in our civic culture stems from people feeling unsafe and insecure. The immigrant Muslim children Glenn studied learned to feel secure about themselves and their native culture in private Islamic schools and used this security as the basis to interact successfully with our diverse society. They became secure and confident and saw cultural differences as opportunities to learn and grow, not as threats.

The evidence suggests that the choice critics are wrong. Education freedom does not contribute to unhealthy social discourse. When done well, it is part of the solution.

As our country was being formed, states such as Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Virginia adopted state religions that citizens were taxed to fund and expected to follow. In response to this infringement on personal freedom, the U.S. Constitution was amended to include language, called the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses, forbidding the establishment of a government religion and guaranteeing individuals the freedom to practice or not practice religion. These clauses read: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Opponents of education choice programs that allow students to voluntarily use publicly funded education choice scholarships to pay for tuition at religious schools assert that these choice programs are unconstitutional primarily because they violate the Establishment Clause. In essence, legally equating families who freely choose to send their child to a religious school using a publicly funded scholarship with a government coercing people to support a state religion. The courts have made clear this argument has no merit and is dead on arrival. But opponents keep trying.

Teachers unions are the most aggressive opponents of education choice programs. The National Education Association (NEA), the nation’s largest teachers union, says, “Voucher programs drain resources from public schools and funnel those resources to private and religious schools, violating the Establishment Clause.” The second largest union, the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), agrees.

Other prominent opponents concur with the teachers unions’ reasoning. People for the American Way believes that "By using taxpayer money to fund private religious education, voucher programs violate the Establishment Clause.” The Freedom From Religion Foundation (FRF) writes that, "School voucher schemes unconstitutionally entangle government with religion by directing public funds to parochial schools, thereby violating the Establishment Clause."

Americans United for the Separation of Church and State (Americans United) asserts that education choice programs violate both the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses. "School vouchers funnel taxpayer money to private religious schools…This violates the Establishment Clause and the religious freedom of taxpayers."

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) makes a similar argument. "School voucher programs that funnel taxpayer dollars to private, religious schools violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment by compelling taxpayers to support religious instruction and activities. Such programs erode the separation of church and state, a foundational principle of our democracy."

Suggesting that the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses give individual taxpayers the right to circumvent elected representatives and decide for themselves how government spends their taxes is a rejection of democratic governance. Expecting a fire department to check with its local taxpayers to determine whose taxes may be used to fund putting out fires at churches is impractical.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) invents a “constitutional principle” when it claims, "Voucher programs, which divert taxpayer dollars to private, often religious schools, undermine the fundamental constitutional principle of separation of church and state.”

The phrase “separation of church and state” is not a constitutional principle. It does not appear in the U.S. Constitution. Thomas Jefferson used this phrase in an 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut to reinforce the intent of the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses, which is that government should not interfere with citizens’ right to practice or not practice religion unless this practice violates public laws. The state will not allow a religion to construct a building without a government permit or abuse children. The U.S. Constitution requires the relationship between religion and government to be appropriate but not nonexistent.

Beginning with the Zelman v. Simmons-Harris ruling in 2002 and continuing with the 2020 Espinoza v. Montana Department Revenue case and the Carson v. Makin decision in 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently ruled over the past two and a half decades that programs providing public funds to help families pay for educational services offered by religious organizations are constitutional, provided families make these choices freely. These court rulings suggest an Establishment Clause violation occurs only when a family’s decision to use public funds to pay a religious organization for educational services is influenced by government coercion.

Despite the weakness of their legal arguments, the ACLU, AFT, Americans United, FRF, NEA, and SPLC have supported lawsuits in Arizona, Florida, Indiana, Maine, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, West Virgina, and Wisconsin challenging the constitutionality of K-12 programs that allowed families to purchase education services from religious organizations using public funds. But these groups have never legally challenged the constitutionality of prekindergarten and higher education students using public funds to attend religious schools.

Why do they support legally forbidding a high school senior from using public funds to pay tuition at a Catholic high school but look the other way two months later when this same student uses public funds to pay for tuition at the University of Notre Dame? The answer is tribal politics.

Humans are tribal. We are all members of multiple tribes, including tribes organized around political beliefs. To remain a tribal member, we must conform to that tribe’s beliefs, no matter how irrational they may appear to those outside the tribe.

Most of the AFT’s and NEA’s dues-paying union members work in K-12 school districts. Consequently, the AFT and NEA are highly motivated to protect the jobs and compensation of these members by opposing students using public funds to attend private schools that employ non-union teachers. Since most private schools are faith-based, these unions use the Establishment Clause violation argument as a legal and political weapon despite its ineffectiveness.

The NEA and AFT have far fewer members working in prekindergarten and higher education institutions. Consequently, they are less willing to spend money and political capital opposing students using public funds to attend religious schools in these two sectors.

Education choice opponents such as the ACLU, Americans United, SPLC, and most Democratic Party elected officials, are in the same political tribe as the NEA and AFT, and these two unions provide much of the money and grassroots activists that give this political tribe its power and influence. Therefore, these groups conform with the AFT's and NEA’s legal reasoning for opposing publicly funded education choice programs and will continue to do so until the unions change their positions.

At a mid-1980s NEA convention, the delegates overwhelmingly rejected a resolution supporting magnet schools. As the floor manager for this resolution, I remember this defeat well. Opponents claimed magnet schools undermine neighborhood public schools and correctly argued that magnet schools are a manifestation of Milton Friedman’s initial school voucher proposal. A few years later, after thousands of NEA members began working in magnet schools, the union reversed its position and embraced magnet schools.

Today the NEA and AFT’s tribal partners all support magnet schools despite their school voucher lineage suggesting tribal loyalty is stronger than ideological consistency, and tribes will rationalize changing core positions to enhance their economic and political strength.

In Florida, teachers unions are slowly bleeding to death as thousands of unionized teachers leave to teach in a rapidly expanding array of new, non-unionized education settings such as homeschool co-ops, hybrid schools, and microschools. To survive, Florida teachers unions need to begin serving these teachers, including those working for religious organizations.

For more than 40 years, I have argued that teachers need to replace their old-school industrial unionism with a model that can serve teachers in diverse and decentralized settings. If they do not evolve, they will not survive. Nor will some of their tribal colleagues.

Steve Malanga writing in City Journal recently made a rather chilling and well-documented case that a growing number of American men are not simply unemployed but are also unemployable. Malanga writes:

But the workforce woes run deeper. Ever more adults are unemployable because of worsening social dysfunction, changing youth attitudes toward work, and university and public school failures to prepare students for labor-market realities. Drug legalization has made it harder to find laborers who can pass drug tests—essential to work in industries like construction and transport—leading to worker shortages for key jobs, including truck drivers. A crime spike, meantime, will likely create a new generation of convicts, among the toughest people to employ when they reenter society. Soaring mental-health problems add to the ranks of the unemployable. And many firms hesitate to hire new college grads because they often lack basic skills, starting with knowing how to communicate and function within a group, and often have unrealistic expectations about pay and benefits.

The male academic disaster has been evident in outcome data for years. To be sure, our society has problems in addition to this disaster, but the deep failure of our education system to equip boys with the habits and knowledge necessary for success exacerbates all of them. POSIWID applies here: Stafford Beer, a British academic, coined the term that the “purpose of a system is what it does,” known as POSIWID for short. Beer explained that the stated purpose of a system is sometimes at odds with the intentions of those who design, operate, and promote it. “There is after all no point in claiming that the purpose of a system is to do what it constantly fails to do.”

The American education system constantly fails to educate boys.

For example, below shows the average academic growth rate by state for female students in grades 3-8 between 2008-09 to 2018-19 from the Stanford Educational Opportunity Project. The horizontal center line denotes learning a grade level worth of math and reading in a year, dots are states, green dots are good, blue dots are bad.

And here is the same data for male students, who obviously learned a great deal less:

The regulatory capture of American school districts by unionized employee interests began in the 1960s and had more or less been completed by the 1980s. To be sure, some other interests, such as school construction firms, came along for the rent-seeking ride. Perhaps this was all fun and games until someone got hurt, and the now long list of the injured includes a rather large subgroup of students called “boys.”

The Big Lebowski should remain a comedy rather than a prescient documentary.

Norse mythology included the concept of Valhalla. Valkyries flew down to earthly battlefields on winged horses to transport the worthy fallen to that Asgardian great hall of the honored dead. If there were a school choice version of Valhalla, the newly arrived fallen heroes would expect to see many greater thinkers and leaders. You may not have expected to find yourself drinking mead in the afterlife with the likes of John Stuart Mill and Daniel Patrick Moynihan and a great many in-between, but it turns out that death is full of surprises!

In this reimagining of Valhalla, the clear-eyed Milton Friedman replaces the one-eyed Odin in presiding over the hall of heroes. Friedman, whose birthday was July 31, 1912, died in 2006. If he were observing our current efforts from a school choice Valhalla, what would he make of us? Just how many Valkyries would he be sending down over the next couple of decades? A recent piece from Ann Marie Miller of EdChoice provides an answer that rings true:

As we celebrate this milestone and we set our sights on reaching 2 million children, Milton would argue that we’re just getting started and that we need to kick it up a notch.

“I think the headline is very simple: It’s progress but not fast or good enough,” said Robert Enlow, President and CEO of EdChoice. “Milton said that to me 1,000 times. He would say, ‘It’s good progress, but it’s not good enough. Not fast enough, not good enough. We need to go further, farther, faster in order to improve the quality of education and our society.”

“We have a society that can’t read, a society that doesn’t understand history, a society that can fall apart if it’s not capable of holding its citizenry together through democracy’s work. You have to be educated to be democratic. So, we need to improve the quality of education in order to improve our society”, added Enlow.

Milton Friedman was a happy warrior who played a large and rapid role in ending conscription and a slower but steady role in making education more pluralistic and humane, among other things. As you fight the horde of choice opponents, you would do well to remember Friedman’s tenacity and optimism. There is always more room for heroes in the hall.

In the spring of 2023, the Florida Legislature and governor made ESAs accessible to all K-12 students. (Accessible means the state government provided funding for the number of students it projected would use an ESA. Many states make all students eligible but do not provide sufficient funding for all students wanting to use an ESA.) Families, schools, tutors, and other education providers responded immediately. Over 100,000 new student scholarship applications flooded Step Up For Students’ online application system. A surge of new schools and other educational options quickly followed.

Critics complained that allowing all children to access ESA scholarships was wrong because many affluent families can afford to educate their children without public funds. But today we provide all families access to publicly funded district and charter schools, so it seems appropriate to offer all families access to publicly funded ESAs, especially since it costs taxpayers less to educate students through ESAs than in district or charter schools.

While affluent students do benefit from access to ESAs, low-income students also benefit from universal access in ways that many critics and some education choice supporters do not understand.

Today over 405,000 Florida students with ESA scholarships are spending about $3 billion on a wide variety of educational products and services. Educators have responded to this huge demand for services by creating a rapidly expanding array of innovative learning options for families. Low-income students benefit from the additional learning options that other participating students help attract because low-income students have historically been underserved by the current mix of options. More learning options means low-income families have a better chance of finding and accessing programs that meet their students’ academic and social needs.

More learning options also help lessen the transportation challenges many low-income families face.

Underserved groups always benefit when the markets they rely on for essential goods and services are more effective and efficient. And universal access to ESA scholarships is rapidly improving Florida’s public education market. We are seeing in real time the creation of a virtuous cycle between supply and demand. More families using ESA scholarships (i.e., more demand) is encouraging educators to create more innovative learning options (i.e., more supply), which in turn is causing even more families to use ESAs (i.e., more demand), which in turn is causing even more educators to create more learning options (i.e., more supply).

Florida school districts are responding positively to the improvements in the state’s public education market. Researchers have consistently found that as the competition for market share in lower-income communities increases, the performance of district schools in those communities improves.

In 2002, Florida voters approved a referendum making access to the state’s publicly funded Voluntary Pre-Kindergarten (VPK) program universal. The advocates for Florida’s VPK program knew that the long-term viability of this program would be greatly enhanced if all families were allowed to participate. And thus far that has proved to be true. Like Medicare or Social Security, Florida's pre-kindergarten program is available to everyone and politically untouchable.

Allowing all families to access Florida’s ESA programs is having a similar political effect and will help ensure these programs remain available to those students who need them the most. Florida’s low-income students are benefiting from this political reality.

An education reform era policy ended recently as New York lawmakers repealed a law that attempted to remove ineffective instructors from public school classrooms. As Kathleen Moore of the Times Union explained:

Districts can still fire probationary employees, as always. The measures that help them remove ineffective teachers who have tenure, however, have been removed. Repealed were measures that called for an expedited hearing for “just cause” termination and stated that reviews showing a pattern of ineffective teaching would be “very significant evidence” in favor of termination.

In addition, teacher evaluations will no longer have to consider test scores, student growth scores and other measures that the state tried to use from 2010 until when the pandemic hit in 2020.

If you have been hanging around the ed reform water cooler long enough, you will recall when New York City “rubber rooms” were a cause celebre back in 2009. Job security for tenured teachers reached such absurdity that NYC schools would send instructors accused of criminal activity to “rubber rooms” in order to keep students safe. Mind you these people continued to draw their salary and benefits while doing absolutely nothing. Rubber rooms existed because it was almost impossible to fire a tenured teacher.

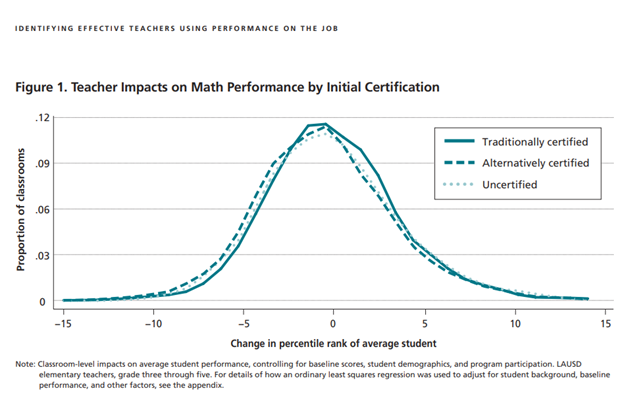

State lawmakers attempted to address this with a statewide evaluation policy that could-in theory- allow school administrators to remove tenured teachers for ineffective instruction. In theory this could have a large impact on average student achievement based upon research such as this chart from a 2006 Brookings Institution study:

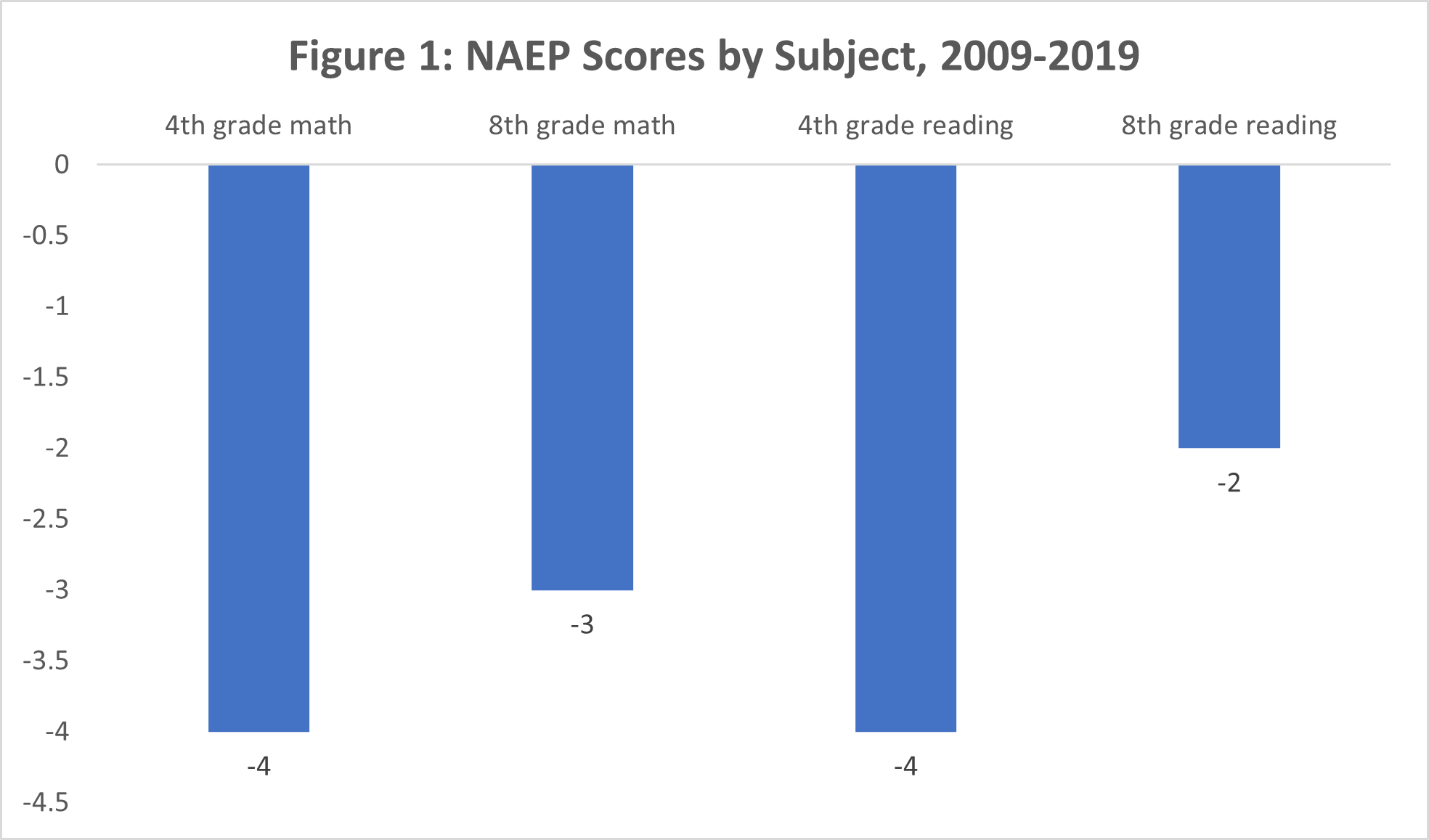

The upshot: Research shows that some teachers are catastrophically poor at getting students to learn (left side of the bell curve) while others are amazing (right side of the bell curve). Obviously what state lawmakers should do is to create a statewide evaluation system to remove the teachers on the left side, and average teacher quality will improve- in theory. As the Times Union article noted, New York had a policy to do just this in theory between 2010 and 2020. Let us then see what happened in New York NAEP scores in practice between 2009 (pre-policy) and 2019 (last NAEP under the policy and before COVID).

Of course, this does not mean that the New York teacher evaluation policy caused New York NAEP scores to decline. It does however mean that the hoped for large improvement in instruction failed to materialize. I don’t know of any data source to confirm or deny this, but I’d be willing to bet a left toe that very few teachers were removed under the policy.

Despite all the Sturm und Drang surrounding this policy at the time, it limped along ineffectually for a decade or so before repeal effectively never being implemented. It’s almost as if school districts have been subject to a deep level of regulatory capture by reactionaries with abundant ability to engage in passive resistance. Reformers bringing technocracy to a politics fight brings to mind Macbeth:

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

It also stands as a great example of Dennis Nedry attempting to get the dinosaur to fetch the stick. Education reform policies require active constituencies in order to work and last. If the supporters of top-down policies recognize this need, they have yet to display much ability to acquire them.

A surefire way to get heads nodding at an education policy conference is to call for dismantling the Carnegie unit.

The question, and a legitimate fear, is whether efforts to replace this flawed measure will lead to something worse.

The Carnegie unit was conceived a century ago by some of the leading lights of American education. They needed a clear way to signal whether students had completed a full course. So they settled on a measure: 120 hours of classroom time.

The fruits of this effort have a major impact on public education. College "credit hours" and "instructional minutes" requirements for K-12 schools derive from the Carnegie unit. Schools receive funding based on the number of units they deliver. Students earn course credits and degrees based on the number of units they complete.

The Carnegie unit remains central to education policy and practice despite its flaws, including the fact that a student can complete a full course without actually mastering the material.

This has spawned a number of efforts to replace the Carnegie unit and related measures of "seat time" with new systems of focused on mastery.

The problem with the Carnegie Foundation's new effort to replace the flawed measure that bears its name is that it doesn't stop at the idea of replacing seat time with mastery. Instead, it involves efforts to devise new measures of student progress for a wider array of domains. As Max Eden of the American Enterprise Institute notes, there's a real risk that these new measures will amplify the same one-size-fits-all thinking that shaped the original 20th century effort:

[T]hey want to evaluate the “whole child," meaning broader human skills such as empathy, communication ability, leadership, and critical thinking. Things that, they reasonably note, parents want and employers demand. The only problem with this approach is that it’s practically and politically impossible and would likely prove counter-productive even if it weren’t.

If teachers want to evaluate math skills, the method is straightforward enough: give the student a math test and see if he gets the right answer. But how could a teacher evaluate 30 students accurately on domains like empathy and leadership? She couldn’t do it herself. So, Carnegie is throwing money at ETS to develop what its CEO Timothy Knowles calls “stealth assessments” for those domains. Color me skeptical that it’s possible to develop psychometrically reliable metrics for such soft skills at all. But if it were possible, it could only be done by AI deeply datamining student behavior.

Zooming out, this is a problem that surfaces in all kinds of debates about public education as we move beyond the industrial era. The Carnegie unit was designed to quantify teaching and learning with a standardized unit that schools and colleges all over the country could easily interpret. It proved so valuable to the batch processing of students that it became ubiquitous.

Now, education systems across the country are trying to create more individualized learning pathways for students that include online instruction, career and technical education, learning outside the classroom, and other approaches that confound assumptions that students should advance based on the time they've spent in class.

States like Wyoming, Kentucky and Vermont are working on approaches that fund schools or give students credit based on the knowledge and skills students demonstrate. A relatively new Arizona law gave public schools flexibility over how their students spend up to half of their learning time. This has helped unleash a wave of new learning environments that challenge conventions about what schooling can look like.

A few simple principles are at work. Learning can happen anytime, anywhere. And students can show what they know by completing a task or passing a test. It no longer makes sense for schooling to revolve around Carnegie units or other measures of “seat time.”

Freeing schools from industrial-era assumptions will help move a school system built to process students in batches to one that embraces their individuality. This transition is bound to be uneven and messy. Jal Mehta of Harvard University has described the work ahead like this:

If we are trying to create a world where students have more choice and flexibility, we are unlikely to do that by replacing the Carnegie Unit with some other single set of measures of performance competency. Instead, we should seek to diversify both how we count learning and what kinds of learning count and do so with the spirit of humility that a task of this magnitude requires.

This seems wise.

It would be a mistake to double down on a flawed industrial-era assumption—that learning can readily be distilled into tidy measures that are legible across diverse institutions—and extend that flawed assumptions into so-called 21st century skills like leadership or collaboration. Instead, we need to make peace with the idea that different families and educators will approach education with different goals and value systems. They will need diverse measurement systems to match.