A recent interview by Tyler Cowen of John Arnold has been making the rounds in ed reform circles, see Michael Goldstein’s write up here. Here is a taste of the interview:

Tyler Cowen: There’s a common impression—both for start-ups and for philanthropy—that doing much with K–12 education or preschool just hasn’t mattered that much or hasn’t succeeded that much. Do you agree or disagree?

John Arnold: I agree. I think the ed reform movement has been, as a whole, a significant disappointment. I think there have been isolated pockets of excellence. It’s been very difficult to learn how to scale that. I think that’s largely true of many social programs or many programs that are delivered by people to people, that you can find a single site that works extraordinarily well because they have a fantastic leader, and that leader might be able to open up a few more sites. But then, when you start to scale it to 50 sites, and start to go across the nation, it all mean-reverts back to what the whole system is providing.

“We’re a dispirited rebel alliance of do-gooders,” Goldstein writes gloomily, but the underlying premises deserve scrutiny, as it strikes me as entirely too pessimistic. Let us for instance look at the academic growth rates for charter schools in Arnold’s home state of Texas as recorded by the Stanford Educational Opportunity Project. Each dot is a Texas charter school, and green dots on or above the zero line display an average rate of academic growth at or above having learned one grade level per year:

This chart deserves a bit of your time to marvel at. While receiving far less total taxpayer funding per student, the Texas charter sector has not only created a large number of schools with high academic growth, but they also place competitive pressure on nearby district schools to improve their academic outcomes. Texas charter schools have not cured the world’s pain, nor have they dried every tear from our eyes. It is hard for me, however, to view it as anything other than a tremendous academic success, and Texas is not alone. Here is the same chart for charter schools in Arizona:

Again, we see far more high academic growth green-dot schools than low academic growth blue-dot schools. Once again, this sector is a bargain for taxpayers, and the sector placed competitive pressure on districts to improve. By the way, Arizona has a larger number of charter schools in low-poverty areas than Texas. That helped crack open high-demand district schools to open enrollment, which is why a real Fresh Prince can go to school in Scottsdale but not in Bel Air or Highland Park in Texas, which opened a vast new supply of choice seats in school districts. The do-gooder rebel alliance, it turns out, made a serious political and educational error when they effectively in a variety of ways excluded suburban areas.

You live and (hopefully) learn. Speaking of Bel Air, behold the magnificence of the academic growth of California’s charter school sector:

Oh, and then there is the 2024 NAEP to consider:

If you do not live in a state whose name starts and ends with the letter “o” you are likely to be happy with your charter sector’s performance vis-à-vis districts, which admittedly, is a low bar. Of course, all this data is messy and neither the growth measures developed by Stanford nor the NAEP proficiency data above capture long-term outcomes- such as do schools produce good and productive people who are well-prepared to exercise citizenship. We are looking through a glass darkly.

The do-gooder education reform alliance should indeed take stock of which efforts produced meaningful results, and which proved to be costly quagmires, and recalibrate their efforts accordingly. To paraphrase the Bard: the education reform movement has 99 problems, but the inability to scale success in choice programs ain’t one.

Opponents of education freedom, facing a series of legislative defeats, have responded by going off the deep end with conspiracy theories and crackpot fables. The formula works something like this: start with tortured and incomplete reading of the research on school choice which ignores a large majority of the findings and studies. Add a fabricated history of the K-12 choice movement that ignores the likes of Thomas Paine and John Stuart Mill, and that implicitly requires you to believe that such prominent left of center luminaries such as Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Jack Coons, Stephen Sugarman and Howard Fuller (among many others) were either knowingly or unknowingly part of a vast right-wing conspiracy. The bards singing this saga also want you to ignore the fact millions of Black and Hispanic families have voluntarily entrusted choice schools with the education of their children. This vast right-wing conspiracy is a racist vast right-wing conspiracy meant to destroy public education!

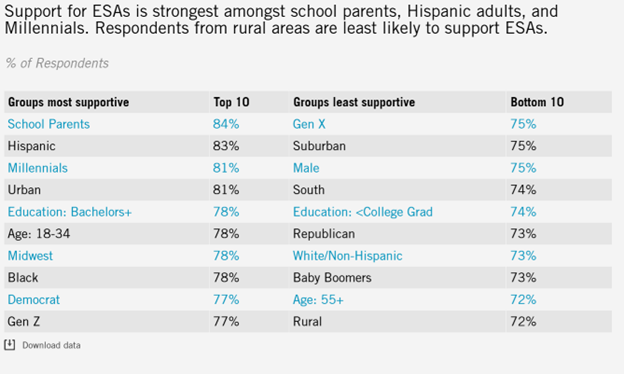

Quite appropriately, neither lawmakers nor teachers seem to be buying much of this double-plus good duck-speak. EdChoice and Morning Consult released conducted a national survey of K–12 teachers. In addition to hopeful signs of optimism regarding the teaching profession and some signs of improvement in student behavior and absenteeism, the survey found strong support for ESA policies:

Public school teachers send their children to private schools at approximately twice the rate of the general public. Little surprise there, as they have a front row seat to district dysfunctionality. The Ed Choice survey also shows strong support for vouchers, charter schools and open-enrollment policies. Despite a non-stop agit-prop effort by unions, most teachers support families having options.

Public school teachers send their children to private schools at approximately twice the rate of the general public. Little surprise there, as they have a front row seat to district dysfunctionality. The Ed Choice survey also shows strong support for vouchers, charter schools and open-enrollment policies. Despite a non-stop agit-prop effort by unions, most teachers support families having options.

The current debate over ESAs in Texas has brought irresponsible claims about the Edgewood Horizon program back to life. A voucher program funded by philanthropists, Edgewood Horizon made all Edgewood Independent School District students (located within San Antonio) eligible to receive a voucher to allay private school expenses. The Horizon program ran from 1998 to 2007, peaking at approximately 16% of Edgewood’s enrollment. Research on choice programs consistently finds positive competitive effects when districts are exposed to competition; as the ability of district students to exit to other options increases, so too do district scores. Choice opponents have been claiming Edgewood as a cautionary tale, but the available evidence demonstrates that Edgewood ISDs academic performance and financial trends were consistent with the research findings on the impact of choice.

Texas choice opponents of 2025, like Jurassic Park scientists, have cloned previous claims about this old program, and set them loose in the current debate. A recent San Antonio media report revisited the claims of Horizon program opponents Diana Herrera and Aurelio Montemayor:

“‘There’s like 1,000 school districts … and out of every school district in the state of Texas, Edgewood was the one selected. And once again, we had zero low-performing schools,'” (Herrera) said. “'So why did they come to Edgewood? The word was because they wanted to destroy us.’”

Herrera remembers the district cutting resources, expanding class sizes by combining smaller classes and cutting positions as the program expanded.

Students from all 23 campuses used vouchers, according to Montemayor, an educational specialist for IDRA, which opposes voucher programs.

“’What was happening at Edgewood was very painful,’ Montemayor said. ‘You had larger classes and they couldn’t shut down a school or hire more teachers. It was very difficult.’”

Was the Edgewood Independent School District destroyed, or for that matter visibly damaged? The Texas Education Agency keeps extensive academic and financial records on school districts. In 1997-98 the Edgewood Independent School District spent $85,695,522. By 2008 this total expenditure had not declined but rather had increased to $95,093,331. Spending per pupil went from $6,060 to $9,039 during the same period. Average teacher salaries increased from $32,753 to $48,742 during the same period. By the end of the Horizon program, Edgewood ISD total expenditures stood at an all-time high and per pupil funding exceeded the statewide average.

Consistent with decades of research results, Edgewood ISD’s academic results also improved during the Horizon period. In 1997 55.1% of Edgewood ISD students taking state accountability exams passed all exams, compared to a statewide average of 73.2 percent. By 2008 this had increased to 57% of Edgewood students compared to a statewide average of 72% statewide. Far from falling apart academically, Edgewood narrowed the achievement gap with the state. Far from “destroying” Edgewood ISD the available evidence shows that district academic performance improved, and the district spent more rather than less money.

Unfortunately, the Horizon program ended in 2007, and the recent academic results of the Edgewood ISD do not indicate that the incremental academic progress was sustained after the conclusion of the program. In 2023-24 Edgewood students had one half the rate of meeting or exceeding grade level compared to the statewide average. The cautionary tale from the Edgewood experience is what happens when students lack an exit option, not when they actually hold one.

Public education in the United States is transitioning from its second to third paradigm.

Paradigm shifts in public education occur when larger societal changes force public education to change to meet these new conditions. Current technological advances and the accompanying social changes are pushing public education into a new paradigm and a third era.

To best meet society’s current and future needs, this third paradigm aspires to provide every child with an effective and efficient customized education through an effective and efficient public education market.

A paradigm: The lens through which communities do their work

In his 1962 book, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” Thomas Kuhn described a paradigm as the lens through which a community’s members perceive, understand, implement, and evaluate their work. A paradigm includes a set of assumptions and associated methodologies that guide how communities construct meaning and determine what is true and false and right and wrong.

A paradigm shift occurs when inconsistencies, which Kuhn called anomalies, begin to occur, and some community members begin to question their paradigm’s veracity and effectiveness. As these anomalies accumulate, community members begin proposing new ways of understanding and implementing their work and a prolonged contest emerges between the existing paradigm and proposed new paradigms. If a majority of the community ultimately decides a new paradigm enables them to resolve the anomalies and better understand their discipline, this new paradigm is adopted. In scientific communities, Kuhn calls these paradigm shifts scientific revolutions.

Paradigm shifts are disruptive and revolutionary because they require community members to reinterpret all their previous work and adopt new ways of conducting and evaluating their future work. Senior community members are particularly resistant to changing paradigms because their status comes from applying the existing paradigm over many years. Consequently, paradigm changes are rare and require several decades to complete.

Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity (GTR) was a new physics paradigm that challenged Newtonian mechanics and Newton’s law of universal gravitation (i.e., the dominant physics paradigm at the time). It took over 40 years before GTR gained wide acceptance among physicists. Einstein never won a Nobel Prize for GTR because the Swedish physicists on the Nobel committee refused to accept his new paradigm.

Although Kuhn’s work focused on the role of paradigms in scientific communities, his description of how paradigms function and change is relevant for all communities, including public education. The struggle in U.S. colonial times to transition from a monarchy to a democracy was a paradigm shift. It was a revolutionary change in how government works, was fiercely resisted by those in power, and took decades to complete.

Public education’s first paradigm

Public education’s first paradigm began before the United States was a country, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted the “Old Deluder Satan Act” to ensure the colony’s young people learned scripture. As the name of that early legislation implies, this first era prioritized basic literacy and religious instruction. Most children were homeschooled, and formal instruction tended to be ad hoc, improvised, and organized around the agricultural calendar.

Religious organizations provided most of the structured instruction outside the home in the 1700s and early 1800s. Children and adults attended Sunday schools, and communities organized what today we would call homeschool co-ops, which allowed rural children to receive instruction when their chores permitted.

The federal government supported public education through the U.S. Postal Service by subsidizing the distribution of magazines, pamphlets, books, almanacs, and newspapers, and establishing post offices in rural communities. By 1822, the U.S. had more newspaper readers than any other country.

Public education’s first paradigm started failing in the early 1800s as innovations in transportation and communications began connecting the country and promoting more industrialization and urbanization. About 90% of Americans lived on farms in 1800, 65% in 1850, and 38% in 1900.

This transition from rural to urban created childcare needs. Increased industrialization necessitated a more highly skilled workforce. And concerns about social cohesion grew as the growing country welcomed immigrants from Ireland and later from Southern and Eastern Europe. These were demands the informal, decentralized, and family-driven first public education paradigm was ill-equipped to meet.

Public education’s second paradigm

In 1852, Massachusetts passed the nation’s first mandatory school attendance law. This accelerated public education’s shift from its first to second paradigm.

The massive influx of European immigrants beginning in the 1830s was a primary reason Massachusetts decided to make school attendance mandatory. The U.S. experienced a 600% increase in immigration from 1840 to 1860 compared to the prior 20 years. Most of these immigrants were illiterate, low-income, and Catholic. Massachusetts’ mandatory school attendance law was intended to help turn these new immigrants into “good” Americans, meaning they needed to be literate, financially self-sufficient, and well-versed in Protestant theology.

Protestant hostility toward Catholic education in the U.S. continued deep into the following century and included the infamous Blaine Amendments that many states adopted in the late 1800s to forbid public funding of Catholic schools, and the 1922 constitutional amendment in Oregon that required all students to attend Protestant-controlled government schools.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Oregon amendment unconstitutional in its 1925 decision Pierce v. Society of Sisters, ensuring every American family had the right to choose public or private schools for their children. This ruling would later help make public education’s transition to its third paradigm possible.

By 1900, 31 states had passed mandatory school attendance laws. While these laws were not initially well enforced, they did significantly increase school attendance, which created management challenges.

As David Tyack chronicles in “The One Best System,” a history of how this first paradigm shift unfolded in America's cities, a new class of professional administrators, known as schoolmen, set out to modernize public education practice and infrastructure. One-room schoolhouses serving students were no longer adequate, so public education began adopting the mass production processes that enabled industrial manufacturers to create large numbers of products at lower costs. The most famous example was the assembly line that Henry Ford created to mass produce affordable Model Ts.

This new industrial model of public education replaced multi-age grouped students with age-specific grade levels that functioned like assembly line workstations. Just as Ford’s assembly line workers were taught the skills necessary for their workstations, public school teachers were trained to teach the skills associated with their assigned grade level, and children were moved annually from one grade level to the next en masse.

Mississippi became the last state to pass a mandatory school attendance law in 1918. By then the bulk of multi-aged one-room schools were being replaced with larger schools that reflected the best practices of 19th century industrial management. This was the paradigm through which government, educators, families, and the public were now seeing and understanding public education. This change marked U.S. public education’s second paradigm.

Ford famously told customers they could have any color of Model T they wanted provided it was black. Public education adopted this one-size-fits-all approach to increase efficiency. Car consumers began demanding more diverse options over the next several decades, and so did public education consumers. The auto industry diversified its offerings much quicker than public education because it faced competitive pressures the public education monopoly did not. But in 1975, President Gerald Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which required all school districts to begin adapting instruction to serve special needs students. This was the first instance of government requiring public education to provide a large group of students with customized instruction.

Public education’s third paradigm

This expansion of instructional diversity accelerated in the late 1970s and early 80s as school districts started creating magnet schools to encourage voluntary school desegregation. The school district in Alum Rock, California even experimented with a short-lived voucher program that fostered an ecosystem of small, specialized learning environments that today would be called microschools.

Most of the beneficiaries of early magnet schools were white middle-class and upper middle-class families who were attracted by the additional resources and high-quality specialized instruction. But magnet schools created for desegregation could serve only a limited number of students. In response to political pressure from influential constituents, school districts began creating magnet schools unrelated to desegregation, which expanded and normalized specialization and parental choice within school districts and accelerated the transition to public education’s third era.

Florida added significant momentum to this transition with the passage of its 1996 charter school law, the founding of the Florida Virtual School in 1997, and the 2001 creation of the nation’s largest tax credit scholarship program.

Two decades later, the COVID-19 pandemic further hastened public education’s current paradigm shift. Magnet schools, virtual schools, charter schools, homeschooling, open enrollment, homeschool co-ops, and tax credit scholarship programs were already expanding nationally when COVID arrived in March 2020. The pandemic turbo charged the growth of these options and newer options such as microschools, hybrid schools, and education savings accounts (ESAs).

Just as 19th century innovations in communications, transportation and manufacturing led to public education’s first paradigm shift, the rise of digital networks, mobile computing, and artificial intelligence are transforming all aspects of our lives, including where and how we work, communicate, consume media, and educate our children. These technical and societal changes are driving a decline of trust in institutions that no longer enjoy a monopoly on public information. They are also driving increased demand for flexibility to determine when, where, and with whom teaching and learning happen. Public education has begun to adopt a paradigm more aligned to 21st century demands, which include parents gaining more power to decide how their children learn.

Government’s changing role

Government’s role in public education will be impacted by a new public education paradigm that reflects these ongoing technical and cultural changes. Under the second paradigm, government had a near-monopoly in the public education market. This quasi-monopoly undermined public education’s effectiveness and efficiency because it failed to take full advantage of the knowledge, skills and creativity of students, families and educators.

In public education’s third era, government will regulate health and safety and help facilitate support services for families and educators but will no longer be the dominant provider of publicly-funded instruction. This regulatory and support function is like the role government currently plays in the food, housing, health care, and transportation markets. Most of the responsibility for how children are educated will shift from government to families and the instructional providers families hire with their children’s public education dollars.

Shifting government’s primary role from instructional monopoly to market regulator and supporter will require operational changes. Families will be able to choose from a plethora of instructional options and will need access to information that allows them to make informed decisions, as well as education advisers who can help them evaluate their child’s needs and develop and implement customized education plans to meet these needs. Government will need to ensure data accuracy and truth in labeling – much as it currently ensures food labels accurately describe what’s in the package.

Third paradigm issues

Providing each child with a high-quality customized education through a more effective and efficient public education market will require public education’s stakeholders to rethink all aspects of how it operates. Here are some issues we will need to address.

Public education’s third paradigm has old roots

In 1791, Thomas Paine proposed an ESA-type program for lower-income children in “The Rights of Man.”

“Public schools do not answer the general purpose of the poor. They are chiefly in corporation towns, from which the country towns and villages are excluded; or if admitted, the distance occasions a great loss of time. Education, to be useful to the poor, should be on the spot; and the best method, I believe, to accomplish this, is to enable the parents to pay the [sic] expence themselves.”

Paine’s recommended funding method was, “To allow for each of those children ten shillings a year for the expence of schooling, for six years each, which will give them six months schooling each year, and half a crown a year for paper and spelling books.”

Over 150 years after Paine’s proposal, Milton Friedman proposed a similar but more comprehensive plan in 1955. Many of the third paradigm’s core ideas existed in the 1700s prior to the industrial revolution. But they were not technically or politically feasible.

Thanks to modern technology and a growing acceptance of families’ rights to direct their children’s education, these ideas are viable today. We can now provide every student with an effective and efficient customized public education. While all students will benefit from customized instruction in a more effective and efficient public education market, lower-income students will benefit the most because they have historically been the most underserved by the current government monopoly. Underserved groups always benefit greatly when the markets they rely on for essential goods and services are more effective and efficient.

Public education’s transition to its third paradigm is happening faster in Florida than in other states. Over 500,000 students using ESAs is rapidly improving Florida’s public education market. Floridians are seeing in real time the creation of a virtuous cycle between supply and demand. More families using ESAs is encouraging educators to create more innovative learning options, which in turn is causing even more families to use ESAs, which in turn is causing even more educators to create more learning options. These rapidly expanding options increase the probability that all students, but especially lower-income students, can find and access learning environments that best meet their needs.

Public education’s first paradigm shift took about 100 years to complete (1830-1930). This second transition began around 1975 and will likely also take about 100 years to complete nationally. Like all paradigm changes, this one is proving to be a long slog. But larger societal changes will help ensure this transition’s success.

For we who grew up tall and proud

In the shadow of the mushroom cloud

Convinced our voices can't be heard

We just want to scream it louder and louder and louder

— Queen, Hammer to Fall

Recently we reviewed in these pages' election returns by generation showing that Vice President Kamala Harris won a majority of most generations but decisively lost Gen X, and thus the election as a whole. We Gen Xers shrugged off the daily looming prospect of global thermonuclear annihilation. Latchkey kids had more pressing things to concern themselves with. Worse still, we survived the cultural oppression of the Baby Boomers and their allegedly “classic” rock playing the same seven songs on infinite radio repeat. Punk, funk, new wave, alternative, grunge — please just give us something else to listen to!

But I digress; in addition to our shared childhood experiences, many in Gen X were the parents of school-aged children during the COVID-19 dumpster fire. This made many see red far more than even having to listen to Stairway to Heaven 18,589 times. K-12 traditionalists/reactionaries might hope to wait out the Gen X generation — some of us have become grandparents — we can’t live forever. Delightfully, still greater challenges for the status-quo tribe loom in the immediate future.

Polls, like the one above from Ed Choice, show that both Millennials and Gen Z show higher support for school choice than either Gen X or Baby Boomers. This is hardly surprising. There were only three channels on television (four if you count PBS) when Gen X was young, and we were thrilled when cable television came along and provided an additional 50 or so channels. Young people these days can stream anything, anytime, anywhere. Future generations will not even understand the phrase “cutting the cord” as they won’t have ever experienced a cord to begin with.

It's hard to imagine public education remaining one-size-fits-all in a world of ubiquitous customization. Democracy can be terribly unforgiving to candidates who attempt to give voters what they think they need rather than what they want. Ultimately this points to a bipartisan future for K-12 choice.

Chuck Todd for instance noted on election night:

Both Florida and Texas have been very aggressive about expanding school choice. Where have Republicans made the greatest gains among Hispanic voters? Florida and Texas. So, education, the economy, those issues, bread and butter issues, and that is how they talk to them. I’m not saying Democrats weren’t, but the cultural issues don’t play as well with Hispanic voters as they may with college-educated whites or even African Americans.

Political parties don’t generally volunteer to play the role of the nail indefinitely; it’s better to be a hammer. Gen Xers are old enough to have seen a bipartisan coalition for choice come, and to have seen it go. Will we see an effort to get a new bipartisan coalition rushing headlong as a new goal, or will we be waiting for the hammer to fall again?

Stay tuned.

By Shaka Mitchell

After this month’s election, which has resulted in a surprising Republican trifecta, the first action GOP lawmakers should take is to pass and sign the Educational Choice for Children Act (ECCA). This bill aims to provide educational opportunities outside the public school system for millions of students over the next four years alone.

The push for educational choice has been growing across the country, primarily driven by state legislatures, which control most K-12 education legislation. However, states like California, Kentucky, Colorado, New York, and Michigan have faced challenges in advancing such legislation, largely due to Democratic majorities and significant influence from teachers' unions.

The ECCA would create a federal scholarship tax credit program that allows tax-paying individuals to direct up to ten percent of their adjusted gross income to a Scholarship Granting Organization (SGO). SGOs already grant scholarships to students in 22 states, but they are products of state-level legislation and implicate the state tax code. Therefore, these programs are non-starters in states without personal income tax. The ECCA represents a first at the federal level and just this year the bill made significant progress, having passed the House Finance Committee.

Be like water

While subject to change, if the ECCA passes with a $10 billion cap, it would likely benefit more than a million students from low- and middle-income families. Families would apply to an SGO for a scholarship, and upon receiving one, parents could use the funds for a range of educational expenses including tuition at private schools, online courses, special education services, and tutoring. Some families will likely choose to keep their student enrolled in a public school and use scholarship funds to supplement the experience with technology or tutoring – enhancements normally reserved for more wealthy families.

The federal nature of the ECCA presents a new opportunity to deliver educational options for children in states where state legislatures have been resistant to educational freedom.

California serves as a prime example. Despite substantial investment in public education (on average more than $18,000 is spent on K-12 students in the state), student outcomes remain disappointing. Only 3 in 10 students in 8th grade are proficient in reading, according to the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP).

Earlier this year, and at the behest of the California Teachers Association, the state legislature defeated a proposal that would have created an $8,000 voucher program. Like water flowing around a stubborn obstacle, the ECCA would give donors and parents another option in their quest for an educational best fit.

While not a cure-all, this bill would significantly improve educational outcomes for all children.

Elections matter

Finally, the ECCA allows Republicans to fulfill the responsibilities entrusted to them by voters, ensuring a prosperous future for all children, regardless of their state's political leaning.

Famously, or infamously depending on your point of view, President Jimmy Carter established the Department of Education as a way to further endear himself to the National Education Association (NEA), the country’s largest teachers union. The Department’s creation was the fulfillment of his 1976 campaign promise, and he was further rewarded in 1980 by receiving the union’s endorsement.

In a similar fashion, candidate Trump and many other Republican candidates including Tim Sheehy (MT), Bernie Moreno (OH), Dave McCormick (PA), and Gov. Jim Justice (WV), expressed their desire to support American families through education choice. President Trump was rewarded on election night in large part thanks to increased support among Black and Latino voters.

On election night, NBC News chief political analyst Chuck Todd noted that “Latino voters align more closely to the conservative party [on] school choice.” Many of these voters live in states with little hope of state-initiated school choice legislation.

The ECCA could deepen the bonds between Republicans and Latino voters and bring much-needed opportunities to students who need them most.

— Shaka Mitchell is a senior fellow at the American Federation for Children.

The classroom at Longwings doesn’t look too different from a typical classroom, but much of the the language on the walls is French, and teacher Erica Rimbert (at center) toggles between French and English throughout the day. Rimbert’s daughter, Abilene, sits on her lap.

McALPIN, Fla. – Maybe it stands to reason that in a remote community surrounded by hay fields and pine plantation, students at a new, K-5 microschool would bring baby horses for show-and-tell, and the teacher would secure donations from Tractor Supply to start a garden. But don’t let stereotypes — or tired myths about school choice in rural areas — limit your imagination about the possibilities here.

The academic offerings at Longwings Academy also include coding … and crochet … and French language immersion. As long as the 10 students and their families like it, and they do, the school’s lone teacher can keep doing what she, and they, want.

“To know we don’t have to follow the pacing guide, and the curriculum guide, and do what the district says to do – it’s just liberating,” said Longwings founder Erica Rimbert, another former public school teacher in school-choice-rich Florida who left a classroom to start a school.

Maybe Suwannee County isn’t the first place that comes to mind for education innovation. But another beautiful thing about education choice is it enables resourceful people to launch good ideas, wherever they are.

Suwannee County is Old Florida and Deep South, 20 miles from the Georgia line. It’s best known for the river that shares its name, and it’s so traditional, it didn’t open up to liquor sales (at least legally) until 2011. About 47,000 people call it home, 1,800 of them in unincorporated McAlpin. The latter is big enough for a Dollar General but not a stoplight.

The activities at Longwings reflect the fact that the community it serves has long had strong ties to agriculture. Here, the students pet Trooper, a horse owned by the Rimbert family. Erica Rimbert’s husband, Nick,(right) sometimes rides Trooper to school.

Rimbert and her family moved here last year, wanting a little land to pursue their passion for horses. In southwest Florida, she worked at a district school that served the children of migrant farm workers. Even then, she had fleeting thoughts of starting her own school, but it wasn’t until moving to Suwannee that it became imperative.

The kicker, Rimbert said, was seeing her oldest daughter, then in kindergarten, and her daughter’s peers, not learning basic things their families thought important. In her daughter’s case, it was not having time to fully pick up French, her father’s native language. For some of the other kids, it was not learning more about farming and livestock, even though their families had strong ties to the land.

“That’s what finalized it for me,” Rimbert said. Sometimes with traditional schools, “there are just needs that are unmet.”

Rimbert wasn’t sure families would want what she was offering. Doubts persisted even though a local official told her during the process of securing a school site that “people are going to come out of the woodwork,” and even though 25 families showed up for open house. It wasn’t until the first day of school that she realized this could work.

“People are just looking for something different,” she said.

Even in McAlpin.

Thanks to parent-directed education policies, more can have it. All the students at Longwings use choice scholarships. And in Florida as a whole, 8,558 students in rural counties were using them in 2021-22, according to an analysis we did.

Longwings is a little different from traditional school in some ways, a lot different in others.

It’s in McAlpin’s only strip mall, next to McAlpin Country Diner. Rimbert has the freedom to pivot whenever and however, with instruction and everything else. But her classroom doesn’t look much different from a typical classroom, except for a few signs in French and a French flag that accompanies the American and Florida flags.

Students start the day with the Pledge of Allegiance. They tackle core subjects. They follow Florida state standards. They take formal tests. Most of them take standardized tests, too, though they’re not “high stakes.” (By law, most of the students using choice scholarships in Florida must take a state-approved standardized test every year.)

The French immersion piece is definitely distinctive.

Rimbert toggles between English and French. On Election Day, the students wrote a few sentences that listed, first in English, then in French, what they would do for America if elected president.

The point isn’t just to learn another language, Rimbert said. It’s “to open the door to learning about another world” and yet more worlds beyond that.

“It’s insane. The kids love it,” she said. “They’ve just taken off with the language.”

Critics of education choice would have you believe a school like Longwings “can’t work” in rural areas, even though in Florida, they’re increasingly common. In 2000, the year before Florida’s private school choice programs began ramping up, 62 private schools operated in Florida’s 30 rural counties. In 2023, there were 130.

What’s happening in Suwannee represents that bigger picture. On the one hand, a few hundred families over the past decade have migrated to options beyond district schools. On the other, the impact on district enrollment has been modest.

According to state data:

At Longwings, Tracy Walker uses a Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities for her 10-year-old son, Jarred. He is classified as gifted and diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. At his prior school, he excelled on standardized tests and earned F’s in some classes.

“He was bored out of his mind,” said Walker, a former Army officer and public school teacher who now breeds horses and sells real estate.

Walker said she was willing to take a chance on Longwings because she could tell Rimbert had the chops to deliver a high-quality program, and to tailor a curriculum that worked for Jarred, who loves math and coding. Rimbert “had so much vision on how to stretch them (her students) further,” Walker said. “I felt like it could be a better fit because it was outside the box.”

At Longwings, Jarred can stand up if he feels fidgety. Rimbert shifts him to more advanced concepts as soon as he shows mastery. He and the other students also apply their skills to real-world scenarios, Walker said, for example, by using what they learned in math to determine the length of fencing and the number of fenceposts they needed for their new garden.

Jarred didn’t like school last year, Walker said. But this year, he’s so excited that “he was disappointed when we were out for the hurricanes.”

Rimbert hopes to switch locations next year to a schoolhouse she’s planning on her family’s property. She wants to stay small but thinks she can grow to 25 students without compromising quality.

Like Walker, she doesn’t think rural families are any less likely than other families to want options. If there’s any doubt, she said, it’s only because they haven’t had as many options to access.

Now, with schools like Longwings, “they’re looking and they’re curious,” Rimbert said. At the end of the day, “everybody wants the best thing for their kid.”

McALPIN, Fla. – Maybe it stands to reason that in a remote community surrounded by hay fields and pine plantation, students at a new, K-5 microschool would bring baby horses for show-and-tell, and the teacher would secure donations from Tractor Supply to start a garden. But don’t let stereotypes — or tired myths about school choice in rural areas — limit your imagination about the possibilities here.

The academic offerings at Longwings Academy also include coding … and crochet … and French language immersion. As long as the 10 students and their families like it, and they do, the school’s lone teacher can keep doing what she, and they, want.

“To know we don’t have to follow the pacing guide, and the curriculum guide, and do what the district says to do – it’s just liberating,” said Longwings founder Erica Rimbert, another former public school teacher in school-choice-rich Florida who left a classroom to start a school.

Maybe Suwannee County isn’t the first place that comes to mind for education innovation. But another beautiful thing about education choice is it enables resourceful people to launch good ideas, wherever they are.

Suwannee County is Old Florida and Deep South, 20 miles from the Georgia line. It’s best known for the river that shares its name, and it’s so traditional, it didn’t open up to liquor sales (at least legally) until 2011. About 47,000 people call it home, 1,800 of them in unincorporated McAlpin. The latter is big enough for a Dollar General but not a stoplight.

Rimbert and her family moved here last year, wanting a little land to pursue their passion for horses. In southwest Florida, she worked at a district school that served the children of migrant farm workers. Even then, she had fleeting thoughts of starting her own school, but it wasn’t until moving to Suwannee that it became imperative.

The kicker, Rimbert said, was seeing her oldest daughter, then in kindergarten, and her daughter’s peers, not learning basic things their families thought important. In her daughter’s case, it was not having time to fully pick up French, her father’s native language. For some of the other kids, it was not learning more about farming and livestock, even though their families had strong ties to the land.

“That’s what finalized it for me,” Rimbert said. Sometimes with traditional schools, “there are just needs that are unmet.”

Rimbert wasn’t sure families would want what she was offering. Doubts persisted even though a local official told her during the process of securing a school site that “people are going to come out of the woodwork,” and even though 25 families showed up for open house. It wasn’t until the first day of school that she realized this could work.

“People are just looking for something different,” she said.

Even in McAlpin.

Thanks to parent-directed education policies, more can have it. All the students at Longwings use choice scholarships. And in Florida as a whole, 8,558 students in rural counties were using them in 2021-22, according to an analysis we did.

Longwings is a little different from traditional school in some ways, a lot different in others.

It’s in McAlpin’s only strip mall, next to McAlpin Country Diner. Rimbert has the freedom to pivot whenever and however, with instruction and everything else. But her classroom doesn’t look much different from a typical classroom, except for a few signs in French and a French flag that accompanies the American and Florida flags.

Students start the day with the Pledge of Allegiance. They tackle core subjects. They follow Florida state standards. They take formal tests. Most of them take standardized tests, too, though they’re not “high stakes.” (By law, most of the students using choice scholarships in Florida must take a state-approved standardized test every year.)

The French immersion piece is definitely distinctive.

Rimbert toggles between English and French. On Election Day, the students wrote a few sentences that listed, first in English, then in French, what they would do for America if elected president.

The point isn’t just to learn another language, Rimbert said. It’s “to open the door to learning about another world” and yet more worlds beyond that.

“It’s insane. The kids love it,” she said. “They’ve just taken off with the language.”

Critics of education choice would have you believe a school like Longwings “can’t work” in rural areas, even though in Florida, they’re increasingly common. In 2000, the year before Florida’s private school choice programs began ramping up, 62 private schools operated in Florida’s 30 rural counties. In 2023, there were 130.

What’s happening in Suwannee represents that bigger picture. On the one hand, a few hundred families over the past decade have migrated to options beyond district schools. On the other, the impact on district enrollment has been modest.

According to state data:

At Longwings, Tracy Walker uses a Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities for her 10-year-old son, Jarred. He is classified as gifted and diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. At his prior school, he excelled on standardized tests and earned F’s in some classes.

“He was bored out of his mind,” said Walker, a former Army officer and public school teacher who now breeds horses and sells real estate.

Walker said she was willing to take a chance on Longwings because she could tell Rimbert had the chops to deliver a high-quality program, and to tailor a curriculum that worked for Jarred, who loves math and coding. Rimbert “had so much vision on how to stretch them (her students) further,” Walker said. “I felt like it could be a better fit because it was outside the box.”

At Longwings, Jarred can stand up if he feels fidgety. Rimbert shifts him to more advanced concepts as soon as he shows mastery. He and the other students also apply their skills to real-world scenarios, Walker said, for example, by using what they learned in math to determine the length of fencing and the number of fenceposts they needed for their new garden.

Jarred didn’t like school last year, Walker said. But this year, he’s so excited that “he was disappointed when we were out for the hurricanes.”

Rimbert hopes to switch locations next year to a schoolhouse she’s planning on her family’s property. She wants to stay small but thinks she can grow to 25 students without compromising quality.

Like Walker, she doesn’t think rural families are any less likely than other families to want options. If there’s any doubt, she said, it’s only because they haven’t had as many options to access.

Now, with schools like Longwings, “they’re looking and they’re curious,” Rimbert said. At the end of the day, “everybody wants the best thing for their kid.”

School choice champions Chip Mellor, left, and Caleb Offley, each died last week.

Sad news this week: Two great warriors for education choice, Institute for Justice co-founder Chip Mellor and the Walton Family Foundation’s Caleb Offley, died on the same day. The Wall Street Journal wrote a memorial for Mellor here which reads in part:

Many young lawyers hope for careers in which they can use the law to promote justice and change lives, but few succeed. One who did was William “Chip” Mellor, who died Friday at 73 years old.

Myles Mendoza and Jason Gaulden wrote tribute to Offley, which read in part:

Caleb made a significant and lasting contribution to the field of education philanthropy, and his impact will continue to shape the lives of the many leaders he supported for years to come.

His approach was always selfless and humble. He worked quietly behind the scenes. Caleb never sought the spotlight. Instead, he was deeply committed to elevating others, believing that real leaders don’t care about followers; real leaders care about developing other leaders. That’s exactly what Caleb did throughout his life.

If there were a School Choice Valhalla presided over by Milton Friedman, Valkyries would be depositing Chip and Caleb into the hallowed halls for a rip-roaring celebration and feast. Well done gentlemen- may your memories be a blessing for us to treasure and your lives examples for us to follow.

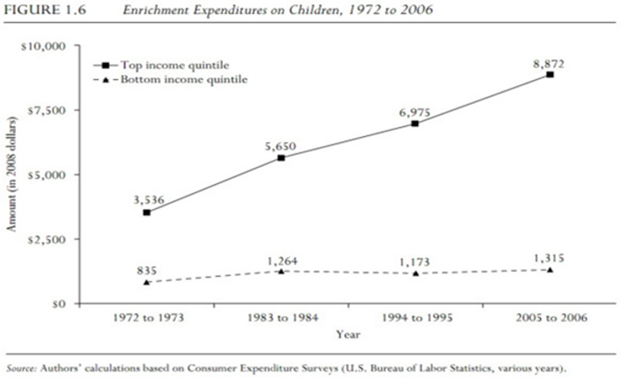

Education Next published a piece recently by Holly Korbey called The Tutoring Revolution, which reads in part:

Recent research suggests that the number of students seeking help with academics is growing, and that over the last couple of decades, more families have been turning to tutoring for that help. Private tutoring for K–12 students has seen explosive growth both nationally and around the globe. Between 1997 and 2022, the number of in-person, private tutoring centers across the United States more than tripled, concentrated mostly in high-income areas like Brentwood. Many students are also logging onto laptops to get personalized digital tutoring, with companies like WyzAnt and Outschool reporting they’ve enrolled millions of students for millions of hours in private, video-based learning sessions that students access conveniently from home. Market reports estimate the digital tutoring market was worth $7.7 billion globally in 2022, with projections of a compound annual growth rate of nearly 15 percent from 2023 to 2030.

Recall as well one of the most fascinating parts of Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story podcast series wherein Lacey Robinson, a veteran teacher in inner-city public schools described taking a teaching position in the suburbs. Robinson wanted to learn what the suburban schools were doing to teach literacy to upper-income students, and then bring it back to the inner-city schools. She discovered that the suburban schools were providing their students with approximately nothing:

“They were learning to decode at home with tutors. I know, because I became one of them.”

If you speak with or poll American suburbanites, they have traditionally expressed a fair degree of confidence in their public schools, which they tended to describe as either “okay” or “good.” Monitor their actions over time, however, and you see that they placed a greater and greater reliance upon tutoring. Most were enrolling their children in public schools, but they were relying upon them less and less and upon tutoring and other private enrichment spending more and more.

In 2015 Wired ran an article called The Techies Who Are Hacking Education by Homeschooling Their Kids. The unstated background message of this article: Silicon Valley families had decided that the time opportunity cost of enrolling their children in a school, even a public school they had already paid for with their taxes, was too high. Key quote:

“There is a way of thinking within the tech and startup community where you look at the world and go, ‘Is the way we do things now really the best way to do it?’” de Pedro says. “If you look at schools with this mentality, really the only possible conclusion is ‘Heck, I could do this better myself out of my garage!’”

Your garage, and perhaps your local Kumon, museums and hackerspaces. Early during the pandemic, Silicon Valley families created a Facebook group called “Pandemic Pods” with spontaneous order scratch to a very itchy group of American families.

The COVID-19 pandemic opened the eyes of many families regarding how much responsibility they should take for the education of their children: all of it. The public school system operates in the interests of its major shareholders (i.e., those deciding school board elections). Broadly speaking, mere taxpayers and families don’t qualify. One can describe the public school system as broken, but you can more precisely observe that it is operating as intended.

If you doubt that last statement, I invite you to attempt to lobby for a meaningful change in the way the public school system operates. You’ll meet all kinds of interesting people. Sadly, most of them will be eager to die on a hill defending the K-12 status quo.

If someone purposely designed an education system to generate inequality, they would have some difficulty exceeding the ZIP code assignment plus tutoring for those who can afford it status quo. The question moving forward is not whether we are going to have more a la carte multi-vendor education. The question is what, if anything, we are willing and able to do to distribute that opportunity.