Editor’s note: This interview, conducted by Robert Pondiscio, a senior visiting fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, with Ashley Berner, director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, appeared last week on the institute’s website.

Editor’s note: This interview, conducted by Robert Pondiscio, a senior visiting fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, with Ashley Berner, director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, appeared last week on the institute’s website.

Last week, two more states—Iowa and Utah—joined Arizona and West Virginia in adopting universal education savings accounts. Several more states, including Florida, Indiana, Ohio, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, might soon follow suit.

The disruptive power of putting parents in control of the lion’s share of state education dollars brought to mind the work of Ashley Berner, who is the director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy.

Her eye-opening 2016 book, Pluralism and American Public Education: No One Way to School, debunked several arguments frequently made by traditional, district-school-only advocates: that only state-run schools can create good citizens or offer equal opportunities to all children, and that exceptions to the American model of government-funded and government-run schools are constitutionally suspect.

“Our imaginations and our public debates remain captive to the existing paradigm in which only district schools are considered truly public,” she has observed. But while universal ESA legislation expands the number of service providers paid for with public dollars, Berner warns that it doesn’t necessarily bring us closer to the plural education systems that are common to most other democracies, or their more capacious ideas about what is – and what is not – “public education.”

Here are highlights of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

You’ve written that, in more plural systems, “many types of schools are considered to be part of the public education system.” How likely is it that Americans can adopt that vision of public education?

The honest answer is, I don’t know. Changing cultural expectations—the taken-for-granted backdrop of a given society—takes time and concerted effort. Social movements, to succeed, require a clear idea that’s adopted and shared by people with different types of capital—financial capital, political capital, moral capital—who can articulate the new idea and translate it into new institutions.

For instance, when William Wilberforce argued in Parliament that slavery was an abomination to the British Empire, he had zero support. Slavery was embedded in the British mercantile system, in their wealth system. But Wilberforce didn’t act alone. He held prestige as a member of Parliament; he recruited merchants to his cause; he worked alongside a network of religious abolitionists.

It took decades, but by the time he died, the slave trade was abolished in the British Empire. It became unthinkable to own another human being. Our country took much longer, sadly, to get there.

I’m embarrassed to admit how little I knew about the education systems of other countries. Until I read No One Way to School, I assumed other countries were just like the U.S., with public schools funded and run by the government.

Me too! I didn’t know this until I lived in England with children and realized that they could attend very different school types that were funded as part of the government’s commitment to the next generation. I had had no idea. I started researching other democracies and realized, my gosh, the U.S. has been stuck in this very narrow, very belligerent paradigm of public versus private, where only one type of school is considered legitimately public education.

I’m not saying that every kind of school is considered a “public school” in plural systems. I am saying that “public education” is, for them, a broad term for the government’s funded commitment to educate the next generation. That commitment holds, no matter how education is actually delivered.

As but one example, the Netherlands funds thirty-six different kinds of schools on equal footing—Montessori, Catholic, Islamic, secular, among others. And yet 30 percent of students still attend what we would consider “district schools.” It’s all part of the public education system.

But even if we are the outlier, I’m not sure Americans are persuaded by international examples.

That’s an astute comment, and I’m sure you’re right in general. However, highlighting the international experience may prove persuasive to progressives who perhaps agree with Democrats for Education Reform but are uncomfortable with the libertarianism of the school choice movement.

If they knew that traditionally left-of-center countries like the Netherlands and Sweden and Denmark take educational pluralism for granted, they might find it more persuasive. The broader school choice movement, with which I largely affiliate, tends to be less interested in international examples, except insofar as they bolster the case for school choice.

Is the argument for ESAs the same as the argument for pluralism?

Not necessarily. It depends on which assurances of quality are written into the laws. Educational pluralism doesn’t just support diverse school types—it also requires all of them to reach a specific academic quality. As such, tax credits and vouchers that are tied to, for instance, nationally normed assessments or site visits by school inspectors fit more readily into pluralistic models. If ESAs jettison all public assurance of quality, I would be pessimistic about their long-term success.

I think the best path is a posture of school-sector agnosticism that asks, “How can we help all schools or programs improve?” That’s what public policymakers in pluralistic countries tend to ask. They don’t compare entire sectors and pit them against each other.

Legitimacy should not reside in one model; we should care about all the models. The best thing that people in public policy can do is put our weapons down and quit demeaning entire sectors.

Bottom line: Do ESA’s move us closer to educational pluralism?

Again, it depends on how they are designed. Educational pluralism rests on civil society, which is distinct from the individual family and from the state. These systems strike a balance between the wishes of parents and the civic imperatives of the state.

Putting all the eggs in either basket can be democratically justified, don’t get me wrong. But I find pluralism arresting because it generates this middle path between the individual and the state. It doesn’t valorize parents, and it doesn’t valorize the state. It creates space for both. I’m interested in creative ways to get us there in a system like ours that’s not used to those concepts.

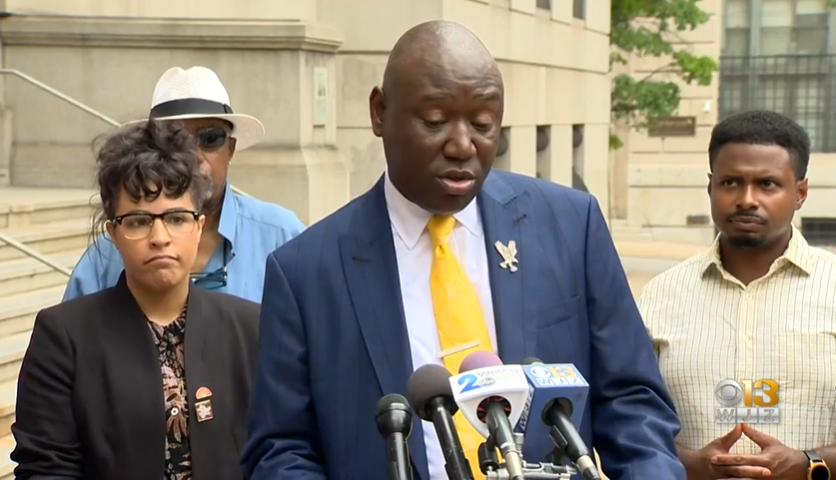

Civil rights attorney Ben Crump, who represented families in the Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, and Flint, Michigan, cases, has come to the aid of a Baltimore couple who is suing the Baltimore school system for alleged mismanagement of funds.

Many families whose schools were closed in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic or who erred on the side of caution about sending their children back to the classroom responded innovatively by forming learning pods – small groups of students led by a teacher or an educator guide.

Now that the crisis has passed, most students have returned to their traditional schools. But many of these innovative solutions have persevered, especially those serving Black families.

Black education leaders who discussed the issue at a recent forum agreed that these tiny private schools are now an established alternative to traditional schools, which they say have failed their children.

Among six participants in a webinar sponsored by the Center on Reinventing Public Education – a group studying the role of learning pods – was Robert S. Harvey, former superintendent of a charter school network in East Harlem, New York, and now president of FoodCorps, a nonprofit dedicated to child nutrition.

Other panelists included Maxine McKinney de Royston, associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison; Jennifer Davis Poon, a partner of learning design and sense-making at the Center for Innovation in Education, a national nonprofit that works with education leaders to promote inclusion; Janelle Wood, founder and president of the Arizona-based Black Mothers Forum; Lakisha Young, founder and CEO of The Oakland Reach; and Chris “Citizen” Stewart, CEO of brightbeam, a national network of education choice activists that produce Ed Post.

The webinar focused on what public education can learn from Black-led alternatives to traditional education, posing questions such as whether such initiatives should exist within the traditional system, which is where about 85% of Black students remain, and whether these alternatives, including homeschooling, which shot up from 3.3% to 16.1% during the pandemic among Black families, promote resegregation.

Oakland Reach founder Young said that’s the reason her organization chose to work within the traditional framework post-pandemic. The group trains parents as tutors, which it calls “liberators,” to help students with academics.

The nonprofit also provides community support, social-emotional enrichment, tech training and economic development. During the early months of the pandemic, Oakland Reach mobilized to set up a virtual hub for students without internet access.

“Our motivation for building outside of the system is because we saw our system crumbling in the midst of the pandemic,” Young said.

Now that the threat has passed, she said, the group is putting caring people out in the community and requiring that the system “re-engage with us in a different kind of power dynamic.”

Contrast that response with Black Mothers Forum, which maintained its small learning environments after traditional schools reopened.

Wood founded the forum in 2016 to provide support to Black parents who believed their children were disproportionately disciplined in district schools. When the schools closed, the Phoenix group opened small groups to educate students whose parents had to work and could not supervise remote learning.

Wood said the parents are happy with the small schools because “they aren’t being called in the middle of the day to pick (their kids) up for minor, minor infractions.”

“Our children were being criminalized and demonized for behavior that was normal for their age group,” she said.

Providing further impetus for the small schools to stay open is Arizona’s rich education choice policy, which offers state funds and makes the schools free for students. This year, Gov. Greg Ducey made history by signing into law a bill that grants education savings accounts to any student who wants one, putting Arizona on the map as the first state in the nation to do so.

But Stewart pointed out that in states that don’t provide education savings accounts, such programs are out of reach for Black students, whose families can’t afford to pay out of pocket. Harvey added that Congress’ refusal to make the expanded child tax credit permanent also deprives families of modest means a potential way to fund education alternatives.

As for whether Black-led alternatives contribute to resegregation, Wood and de Royston responded that Black children, especially boys, already were suffering from discrimination in the system. De Royston called blaming Black parents for resegregating school “a particular form of gaslighting,” especially when white middle class communities already have done that by seceding from urban school districts.

Her comments come as more and more Black parents are growing vocal about concerns over the quality of their children’s public schools. In Baltimore, a Black couple is suing the city school system for mismanagement of funds over accusations about the enhancement of attendance and grades for funding purposes.

In June, an inspector general’s report showed that 12,552 failing student grades were changed to passing between 2016 and 2020. The report prompted Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan to call for a criminal investigation into the matter. The case, which drew national attention, prompted civil rights attorney Ben Crump, who represented families in the Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, and Flint, Michigan, cases, to join the case.

“We knew that Black people were struggling in American schools, but we didn’t know much until we opened those systems up to public scrutiny,” said Steve Perry, head of school and founder of Capital Preparatory Schools, a group of charter schools in the Northeast.

Perry was interviewed on Revolt Black News for a segment called “Black America’s Education Epidemic” in which he said the system has failed Black students since the early 20th century.

“It isn’t a new thing,” he said. “Black people have been trying to find ways out of the system that was designed to undermine their very growth and humanity.”

Public schools historically have been defined by their location. Whether one’s home is in a “good school district” matters. But the last few years have raised important questions about whether tying children to a particular building is wise policy.

Public schools historically have been defined by their location. Whether one’s home is in a “good school district” matters. But the last few years have raised important questions about whether tying children to a particular building is wise policy.

Zoning laws may have made some sense decades ago, but today, they serve little purpose other than protecting established interest groups at the expense of children and families.

Some parents have lofty goals for their child’s school. Yet everyone wants his or her child to be able to read, write, and solve math equations proficiently. Parents need to know that their local public school can teach the basics. Unfortunately, some public schools across the country are failing to meet this rudimentary requirement.

Recent studies show that test scores have plummeted in public schools across the nation during the pandemic. Math scores have decreased in every state. Reading scores fell by the largest amount in more than 40 years. In addition to these poor numbers, many public schools have failed to help students socially and emotionally during these turbulent times. Isolation and depression are up, especially for those in high school.

Despite warnings that this might happen, teachers’ unions argued repeatedly that kids could learn from anywhere. Maybe we should take that claim seriously.

Obviously, kids can learn from home, but children should also be able to learn at the institution that suits their needs. Remote learning, charter schools, micro-schooling, also known as small, personalized private schools, and homeschooling all point to the same question: What is preventing students from learning in the environment of their choosing?

For most kids, the answer is school zoning laws. School zones give local schools a quasi-monopoly over the local area. One of the functions of zoning laws is that they ostensibly ensure that children go to a school near their house; unfortunately, even in that most basic function, zoning laws repeatedly fail.

In Hillsborough County, Florida, for example, possible changes in school boundaries are upsetting some parents, while others hope changes will result in their kids being sent to more highly rated and conveniently located schools.

More perniciously, these regulations stifle innovation and heighten inequality. Public schools in many parts of the country get a substantial amount of funding from local property taxes, which may make financial sense, but it starkly disadvantages low-income children. Parents in low-income school zones have to send their kids to the local school, which typically has significantly worse educational outcomes.

Zoning laws don’t help schools or administrators much either. The system makes schools beholden to teachers’ unions, locking parents and students out of the reform process. This, in turn, breeds an unhealthy lack of trust between parents, teachers, and administrators.

Furthermore, the funding system means that “bad” schools have little ability to financially compete with “good” schools, making things difficult for reform-minded administrators.

Of course, zoning laws don’t prevent all competition. Charter schools, private schools, and homeschooling allow some flexibility. But the success of these programs indicates that the typical defenses of school zoning don’t hold much weight. Kids at charter schools make friends despite not living next to each other. Competition for school choice scholarships would drive down the need to rely on local property taxes.

School zoning laws are a relic from a bygone (and segregated) time without any school choice. In today’s era of dynamism, the downsides to zoning laws far outweigh their benefits. Parents are looking for change. We should give it to them by eliminating the archaic school zoning law requirements holding children back.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Marty Lueken, director of the Fiscal Research and Education Center at EdChoice, and James Shuls, a fellow at EdChoice, first appeared on washingtonexaminer.com.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Marty Lueken, director of the Fiscal Research and Education Center at EdChoice, and James Shuls, a fellow at EdChoice, first appeared on washingtonexaminer.com.

Fifty years ago, public education advocates began fighting for equity in public school funding. They looked forward to a day when every student, even those from disadvantaged backgrounds, could receive a high-quality education regardless of their ZIP code.

And while those advocates made progress in closing funding gaps, dollars and cents alone could never overcome the reality that assigning students to schools means assigning some students to schools that don’t meet their needs.

To promote equality truly, we must also promote educational options.

The future of education spending is one that prioritizes equity, efficiency, and opportunity. As we wrote in our 2019 paper, " The Future of K-12 Funding ," ideal systems of funding K–12 education for children will indicate that we, as a society, desire to serve all students, that we are concerned with being responsible stewards of taxpayer dollars, and that we want to provide the best educational opportunity for every child.

We’re much closer to achieving that vision today than we ever have been before.

With recent legislative action, Arizona expanded its Empowerment Scholarship Accounts , or ESA, program to all K-12 students in the state. This program allows every child, regardless of race, gender, income, or background, to receive a scholarship account worth about $7,000 per year to use at the school of his or her family’s choice. Students with special needs receive an even higher amount, commensurate with their needs.

It is easy to see how this system increases equity and opportunity. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, funding portability would have allowed families to leave the public school districts that stayed closed and send their children to a school that prioritized a return to in-person learning.

We know from the data that students who were able to do this suffered much less learning loss than students stuck in “Zoom school.” Disadvantaged students and students with special needs suffered particularly devastating consequences. Programs like Arizona’s ESA would have made sure those children weren’t left behind.

Or, consider the students stuck in struggling inner-city schools, which outspend their suburban counterparts significantly but still fail to graduate half of their students. ESAs provide an opportunity for escape.

The same is true for the rural student who needs flexibility or opportunities not afforded to him in his local school.

This system of choice also increases efficiency for students and taxpayers. By allowing families to direct their education dollars, Arizona is helping more students find the educational arrangement that works best for them.

This system allows students to access a menu of education-related goods and services since families are no longer confined to traditional school models. This flexibility increases competition among providers, which in turn results in downward pressure on providers to control costs. This is something not seen in the traditional public education system, in which costs continue to skyrocket .

Economist Milton Friedman’s keen insight on how to spend money illustrates this dynamic. He noted we have two options when spending money: You can spend your money or someone else’s money, and you can spend money on yourself or on someone else. We are always more efficient when we spend our own money, and we tend to care more about the quality of goods and services we purchase for ourselves.

The public school monopoly is a lesson on what happens when bureaucrats spend other people’s money on someone else’s children. They have little concern for cost and little care for value.

With an ESA program like Arizona’s, the state equips parents to spend their own publicly funded ESA dollars on their own children. We can expect parents will seek the highest value in education services they can purchase for their children, which will benefit both families and the state alike.

In fact, research is quite clear that the state experiences fiscal benefits from these types of programs.

But this isn’t just about fiscal reform. It’s about shaping up the educational dynamic entirely and reworking it to fit the needs of students and their families better.

By scrapping the old system of residential-based schooling and adopting truly unencumbered choice, Arizona has created a funding system for education that lives up to our values as Americans. The future of school funding has arrived, and Arizona is leading the way.

Which states will follow?

Editor’s note: Don Soifer, author of this commentary, is president of Nevada Action for School Options, whose MicroschoolingNV initiative actively engages in movement building for microschooling in different states.

Editor’s note: Don Soifer, author of this commentary, is president of Nevada Action for School Options, whose MicroschoolingNV initiative actively engages in movement building for microschooling in different states.

A new study from researchers at the venerable RAND Corporation takes the important step of evaluating the academic growth achieved by children at a prominent microschool, the Southern Nevada Urban Micro Academy (SNUMA). The academy was created by the City of North Las Vegas to serve families during the Clark County School District’s pandemic shutdown.

The report, which studied the microschool’s academic growth results during its first school year, 2020-21, found that most SNUMA students made substantial progress based on online platform metrics.

Like many teams behind the thousands of microschools that have been created to serve learners around the country, the North Las Vegas team chose to measure the reading and math gains of the children it served using learning tools with embedded assessments, aligned with academic content standards.

Leaders found this preferable, rather than distracting from learning to participate in more involved standardized assessments, like those used in public school districts. These methods often divert precious time, resources and staffing from other valuable activities, they had concluded.

The researchers wrote that they found SNUMA’s Year 1 evaluation “intriguing because leaders set ambitious goals for students whose learning was assessed as being below grade level.” By relying on interpreting the tools embedded in the digital tools being used by the microschool, the RAND team found that “most students made substantial progress and were assessed as performing at grade level” by the end of that first year.

The first of its kind microschool was the result of an active partnership between the city, which for Year 1 hosted SNUMA in its recreation centers and one library and paid for it out of city funds completely outside of state education dollars, and education nonprofit Nevada Action for School Options, which directed all teaching and learning.

Participation was free for residents who opted out of their public school district to register as homeschoolers and adhere to state requirements as such and included breakfast and lunch.

The microschool and its team of learning guides used an innovative approach to teaching and learning with which its leaders had worked in some of the nation’s highest-performing personalized learning classrooms. Digital tools like Lexia (literacy) and Dreambox and Zearn (math) were used to support personalized learning part of the day, while whole-group, small-group and one-on-one sessions balanced the day to embrace the best of an-person learning experience for children.

Impressively, the researchers observed: “Notably, student race and ethnicity, gender, age and grade did not predict …. progress or ending grade levels.”

Given the rampant equity struggles exhibited by public school systems everywhere during 2020-21, exacerbating pandemic impacts facing the most fragile populations, microschool leaders able to produce such equitable progress should be heartened by encouraging results like these.

Other important aspects of a rich overall learning experience, such as the value of prioritizing social and emotional learning progress, were raised by the researchers, and with good reason. Their analysis fell short of being able to compare the progress by children at the microschool compared with others enrolled in traditional schools.

Even though the learning platforms were aligned to state academic content standards, they observed, many academic researchers prefer to make statistical comparisons based on children taking the same standardized assessments.

These frustrations parallel quite similar circumstances to those in 2015 when RAND researchers, trying to apply their research model to evaluating blended learning models at a handful of sites around the nation, wound up frustrated by real-classroom obstacles like constantly iterating methods and curricula, and the absence of scientific control groups.

After all, what conscientious and innovative educators would choose to deliberately hold back access to progress for any extended time periods when they could instead continually adapt and evolve learning as useful?

Microschooling’s early adopters in 2022 won’t stand still, even for established researchers wanting to study impacts over time, like blended learning in 2015. Understanding that the powerful potential of the microschooling sector is steeped in these smaller, nontraditional learning environments’ ability to create their programs around the particular needs of learners served, and to evolve as do the needs they are addressing.

Thus, the dynamism that helps define the fast-growing microschool sector may pose its own challenges to pure quantitative analysis of their academic performance in comparison with more traditional learning models. Meanwhile, the recognition by researchers that by relying on assessment tools embedded in many digital learning platforms, microschools can track the progress of the learners they serve in different useful ways, will likely prove important to framing future discussions by families, educators, and policymakers alike, about the benefits of such nontraditional learning models.

Nearly 70 years after Brown v. Board of Education rewrote the rules of American K-12 education, pundits and academics are still debating its legacy. And despite nearly universal agreement over the shame and damage done by segregation and resistance to integration, some refuse to reflect deeply on the very flaws of the public institutions and policies they support today.

Nearly 70 years after Brown v. Board of Education rewrote the rules of American K-12 education, pundits and academics are still debating its legacy. And despite nearly universal agreement over the shame and damage done by segregation and resistance to integration, some refuse to reflect deeply on the very flaws of the public institutions and policies they support today.

Leslie T. Fenwick, dean emeritus of the Howard University School of Education detailed the more than two-decade struggle to integrate America’s public schools post-Brown and the many years of fallout that occurred following the loss of what she claims to be 100,000 Black educators at the time.

Fenwick argues that modern post-Brown initiatives aimed at disfranchising Black teachers and students continue to this day. Even while enumerating the ills created by America’s racially segregated public school system, she oddly points at modern reform policies and institutions that are better serving Black students and teachers today than the district-run public schools she prefers.

Fenwick notes that the white dominated public school districts not only resisted racial integration for more than two decades, but also fired many highly qualified Black teachers to give jobs to white ones. According to her calculations, this led to a $1 billion to $2 billion loss in salaries for Black educators and a brain drain among educated and experienced teachers in Black schools.

These losses are still felt today.

Indeed, the percentage of Black teachers has declined overall, falling from 8.1% 1971 to 6.7% today. (It is worth a side note: the percentage of other non-white educators has risen from 3.6% in 1971 to about 14% of the teacher population by 2017-18). Despite there being a majority-minority student population today, most teachers remain white. According to the latest data from the Digest of Education Statistics, white teachers still make up a majority of teachers (79.3%) compared to Black (6.7%), Hispanic (9.3%), Asian (2.1%) and mixed-race (1.7%).

But the target of Fenwick’s ire isn’t the centralized public school system, whose rules and policies are enforced by the whims of whatever political majority is in power at the time. Instead, Fenwick pivots to target alternative teacher certifications, charter schools and school vouchers as “post-Brown policies” akin to the ones used to resist racial integration in the 1950s, 60s and 70s.

However, these modern programs provide better outcomes for Black students and teachers than the district-run public schools she prefers.

Alternative teacher certification programs are designed to help people with college degrees enter the teaching profession without having to re-enter college for additional degree obtainment. Black professionals wishing to enter the teaching workforce make up 13% of the alternative certification track compared to just 5% for the traditional education bachelor’s degree route. In other words, alternative certification may be a more effective way to get educated Black teachers into classrooms.

Charter schools not only educate a proportionally larger body of Black students than traditional public schools, but they educate those students better and are more likely to match a Black student with a Black teacher.

Modern school voucher programs also are an odd target, considering the first modern voucher programs in Milwaukee and Florida both aimed scholarships at low-income Black students. In fact, Florida’s Opportunity Scholarship student population was nearly 100% Black when the teachers union sued to eliminate the program.

Today, Florida’s income-based private school choice programs are 73% non-white. It also is worth noting that students on these scholarships are more likely to attend and graduate college with a bachelor’s degree, a critical factor in producing new teachers.

Fenwick is clearly aware of the flaws inherit in a politically controlled public school system. She writes:

“With curriculums and textbooks nearly all-white in authorship, content and imagery; and, with district leadership, funding, and policy levers controlled almost exclusively by white officials.”

But instead of offering solutions to the current flaws, she condemns education reform and offers instead an alternate history where Black teachers were never fired, resulting in a perfectly functioning public school system today.

“Matters of fact … are very stubborn things.”

“Matters of fact … are very stubborn things.”

Tindal, Will of Matthew Tindal

My Catholic elementary school in Duluth, Minnesota, shared a boundary line with a large public school, East Junior High. In seventh and eighth grades, we kids from Rosary would be sent across that border once a week, the girls to learn skills thought suitable to their sex, the boys to get a sense of jobs like printing and electricity.

East seemed fine, and my parents chose it for ninth grade before my three years at Cathedral High.

By 1968, now in Berkeley, my wife, Marilyn, and I were to get our five progeny schooled roughly half their years in public schools, which at that time were about to achieve racial integration by busing. For the younger three children, our residence was chosen near John Muir Elementary, where they could walk, while Black children were bused in.

The eldest two boys were bused to integrated public middle schools. John Muir turned out fine; but the two years for John and Bob were not so happy, and we switched them all to St. Augustine. From there, the four boys went on to high school with the Christian Brothers, while Mary talked us into Berkeley Public High.

After graduation, none chose a private college; two found successful years in show business; some still pray. We all remain close.

What is my point, if any? It is about Marylyn and myself, who came away with the experience of being responsible human actors. I live in the freedom either to try to bend the world to my own selfish satisfaction, or, in my better moments, to look for the right and good.

My performance at this universal option is not my subject here; but I do want to report that such human responsibility has been a precious part of our lives, confirming that freedom which all of us claim as a fundamental reality. More, it is the only respect in which we humans are born and remain equal.

Thus, I shudder that the media have created a new arena in which the battle pits the word “equality” against “equity.” Worse, it does so, not as the proper term for some reality of our beings, but as a mere historic and semantic preference.

Its essence is a political struggle, in which the left favors “equity” to describe its vision of the great society, making the word a battle cry for many of our public school autocrats. The Center-Right, meanwhile, curses this semantic turn, favoring “equality” as the slogan for the ideal civil order.

Neither side appears to have consulted our dictionaries, which would have the two words synonyms for the practical goal of a just civic order.

What neither of the combatant sects notes is that both they and the dictionaries assume that each word refers only to the design of specific public policy, None of these thinkers note any universal feature of our human nature that might require our moral concern about such matters.

A little history could help here; what was it, if anything, about us humans that made the founders deem us “created equal” and, therefore, endowed with “inalienable rights”? For them it was plain and simple that there was some universally shared fact about human nature, a fact that mandated equal (or equitable?) civic concern for even the least of us.

Call it what you will, there was, and still is, this foundation for human dignity and a proper civil order.

This qualifies our natural equality as an important part of any school curriculum. Of course, this foundational fact is not easy to disengage from the transcendental. Does that make it forbidden to the classroom as an establishment of religion? Or might our schools recognize this as the factual and intellectual justification for the intelligible design of our civil order?

Webster defines the adjectives “free” and “responsible” as follows:

Webster defines the adjectives “free” and “responsible” as follows:

Free: Acting of one’s own will or choice and not under compulsion or restraint; determining one’s own action or choice.

Responsible: Having a capacity for moral decisions and therefore accountable.

These two words, together, declare the status of every rational human who has passed the point of infancy into that hazy stage at which one becomes conscious of a difference between good and evil and of a personal call to decide.

The child thereby becomes “accountable,” though for what, to whom, and just how may remain enduring questions. Webster doesn’t elaborate; his profession was radically different from that of those savants of ancient times who had been variously defining good and evil long before the advent of dictionaries, perhaps soon after the Garden.

Adam had made a certain free and rational choice and enjoyed its immediate object; only then did he experience his accountability. Had he instead opted for obedience, the “accounting” part of the story would, I trust, have been different for him, if not for Eve – and perhaps for us.

Even before his or her own accountability begins to whisper, the infant experiences its reality as a feature of those adults who are “duty-bound to keep me free and happy; they owe me.” But soon comes awareness of his or her own duty of reciprocity that will keep ever broadening to maturity and then beyond. Over time, the child, then the adult, constantly accrues new roles of duty to his/her fellow humans, God (and animals?).

Early on, the child grasps that responsibility to another human can come without anyone’s having chosen so. A new sibling arrives to complicate things at home. Conversely, taking a Scout oath is (presumably) the child’s free choice. In either story, the child’s obligation is real, and his/her awareness of that reality clarifies and intensifies over time.

The course of one’s understanding of duty and free choice is constantly enriched by observation and experience of those adults – typically parents – who know and care, and to whom the child reciprocates (or does not). “They teach me; they are human individuals specifically responsible for my well-being. When it comes to my time for school, they will know what’s best for me.”

To this point, the story is a positive one of personal responsibility and love like none other in the experience of parent and child. But … not every child is lucky. Parents are imperfect; some will decide less prudently simply for lack of information or experience.

It is the duty of society to assist the natural love and unique experience of any less-ready parent to express itself in making a responsible decision for little George. The uncertain parent should have available such basic information of a school market as may be relevant to prudent decision.

The “market,” of course, should include those state schools, at last, truly “public,” plus private schools which agree to abide by a few necessary rules providing both the family and the unique mission of each school.

Such a system of prudent accountability for the benefit of parents already exists – that is, for the family of means. Well-off parents choose their residence in that specific neighborhood which they can afford, and which has a “public” school which they deem acceptable for young Bob. The likeness to the private market is inescapable: In this case, the buyer secures the best product he/she can afford – by choosing the location of the family residence.

But if these parents can’t afford to live anywhere besides the cheapest inner-city attendance zone, their freedom, authority, and responsibility for the child 180 days a year – their dignity as citizen – ceases. It is transferred to whom? To nobody.

There is no person in the state school system who ever heard of either Bob or you, his mother. Your poverty has prepared a cell for the child. It is called P.S. 62. Such seizure of authority from the lower-income parent may or may not succeed in teaching bob his 3 R’s; it cannot help but teach both child and parent that they are anything but “free and responsible.”

We have imposed this semi-detention system upon the un-monied family for nearly two centuries. Is it any wonder the inner-city parent and child have become a media symbol of our disorder and national distress? The child does his 12 years in a cloister run by strangers who, every so often, order his parents to come hear the news and get their orders for Bob’s improvement.

Young Bob listens. And he watches as, for that dozen years, the parents, liberated of responsibility and stripped of their dignity, too often take the message as an invitation to become that idle human that our state governments and the media, since the 1840s, have chosen to portray them.

Deliverance from this grossly impersonal (and inefficient) system by subsidies to parents (instead of government school) may at first seem “the same difference.” After all, the parent’s role is every bit as undemocratic. The decisive difference is that it is also uniquely and intensely personal; the comfortable family experiences it so, as well I recall.

Given choice for the bottom half, some of these newly liberated and empowered, responsible parents will, for a few years, need information and advice. Most will get it privately, many from friends and churches; but the state would have its resources available to help in the parent’s process of sophistication.

At all events, this will no longer be 1840 with the poor caste as a civic menace. If threat there be, it lies in today’s class division of the American mind.

Finally, the child’s own role grows with age. Well-off and caring parents have always increasingly valued their teenager’s waxing insight and readiness for responsibility. I cannot imagine that this same experience of reality and hope could be anything but good for child or parent, regardless of wealth.

U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Florida) partnered with U.S. Rep. Frederica Wilson (D-Florida) to usher the Commission on the Social Status of Black Men and Boys Act, establishing the Commission on the Social Status of Black Men and Boys, through the Senate and House. President Donald Trump signed the bill into law in 2020.

U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Florida) recently joined the Brookings Institute to discuss his role in the Commission on the Social Status of Black Men and Boys, which exists within the U.S Commission on Civil Rights’ Office of the Staff Director.

The bipartisan, 19-member Commission, comprised of congressional lawmakers, executive branch appointees, issue experts, activists, and other stakeholders, examines social disparities affecting Black men and boys in America and recommends policies to improve upon or augment current government programs.

Included in Rubio’s conversation with the Institute on why the Commission’s work matters, he spoke passionately about the importance and value of education choice. Here is an excerpt:

It’s one of the reasons why one of the things I’ve been supportive of is school choice. Not because I’m anti-public schools. I went to public schools. Some of the best public schools in America are public schools in South Florida. But I also have seen firsthand — not because I read about it — someone be taken through an opportunity scholarship, which is funded through corporate donations to Step Up For [Students] in Florida, be able to go to a private school or a school of their parents’ choice, where they are exposed to all kinds of things that expand their horizons.

Suddenly, they realize there’s this whole other world out there — job and career opportunities that they may never have been aware of if their life had been isolated to just the 15, 20 square blocks of their neighborhood and their local community. That is a life-changing opportunity that suddenly sparks all sorts of interest. I’ve seen it happen over and over again.

People who never thought about becoming an engineer or a pilot, or going into the service academies, or going into law or science, whatever it may be, because they didn’t even know that those jobs existed, because they don’t know anyone who has jobs like that. To me, that’s extraordinarily important, and it’s one of those things that I think are underappreciated.

How much value that has in young people’s lives, to be exposed to those opportunities and to expand horizons early on.

You can read more of Rubio’s comments here.

Dorothy Mae Johnson, who attended Daniels School in the 1940s and 50s, is helping Florida SouthWestern State College history professor Brandon Jett put a spotlight on Selma Daniels’ story. If Daniels was alive today, she would have multiple options to create a Daniels School with more resources and more freedom.

LaBELLE, Fla. – Nearly a century before micro-schools became a thing, a woman named Selma Daniels created one for Black students not far from the Everglades.

In 1930, Daniels and her husband moved from Alabama to the tiny town of LaBelle, 30 miles east of Fort Myers. There was no school in LaBelle for Black students. The closest ones were 30 minutes in one direction, 45 minutes in another – and that’s if students could get a ride. So Daniels did what pioneering educators have always done: She created her own school – in this case, in her home.

The story doesn’t end there. According to former students, local history buffs, and Brandon Jett, a history professor at Florida SouthWestern State College, the principal of the all-white public school approached Daniels when a new sawmill drew more Black residents. If you can find a place to hold classes, he said, we will pay you to teach. Daniels’s husband went to the school board. It agreed to provide a building.

The Daniels School was born.

For three decades, the Daniels School educated nearly every Black student in LaBelle from grades 1 to 6. It closed in 1966. But former students still remember the school under the oaks, the sunlight streaming through the windows, the teacher with the long, red fingernails.

Selma Daniels

If students acted up, Selma Daniels might pinch them or tug an ear. But she never raised her voice. She kissed away the pain when students got hurt. And if they struggled with a lesson, she would go over it until they got it. “You’re going to learn,” she’d tell them, putting her face close to theirs. “You’re going to have it right before you leave.”

“Selma Daniels was the best thing to happen to LaBelle,” said Dorothy Johnson, who attended Daniels School in the 1940s and 50s. “If it wasn’t for her, there would be no us.”

The story of Selma Daniels is reaching a wider audience thanks to Johnson and Jett. A few years ago, Johnson convinced the city council to re-name the road that runs past the school to Selma Daniels Avenue. Jett, meanwhile, has surfaced tantalizing details about Daniels’s remarkable life, and deftly persuaded local media to shine a spotlight.

“I didn’t have much work to do to make this story fantastic,” Jett said. “It’s struggle. It’s perseverance. There was a need and a vacuum. (Selma Daniels) saw that, and filled it, and by all accounts filled it successfully.”

The old school still sits in the same working-class, Black neighborhood, ringed by churches and, at this time of year, awash in the smell of orange blossoms. There is talk of restoring the building, perhaps for a museum. There is also fundraising for a Selma Daniels Scholarship Fund, which will pay college tuition for a local student who wants to become a teacher.

It's sweet timing that Selma Daniels is getting attention now.

As the landscape of public education changes to yield more and more options, more and more teachers are finding they have the power to create them. Examples in Florida abound. (For starters, see here, here, here, here, here.)

In a way, these teachers are going back to the future. Because there have always been teachers who saw a need and found a way.

In 1904, Mary McLeod Bethune created a private school for Black students in Daytona. To keep it running in the early years, she biked around town to solicit donations and helped students bake sweet potato pies for fundraisers.

In the 1970s, Marva Collins left Chicago public schools to create a private school, initially in her home. The achievement results were so outstanding, Collins inspired a TV movie starring Cicely Tyson.

Between 1917 and 1932, Black communities throughout the South helped build 5,000 Rosenwald schools. Philanthropist Julius Rosenwald offered the seed money, but Black communities often raised the bulk of the funds and secured the land. Officially, the partnership stipulated the schools fell under the jurisdiction of white school boards. But unofficially, Black residents often exercised power over hiring and curriculum.

The ironic result: All-Black schools, separate and unequal, and yet, beloved.

The Daniels School started with about 20 students and grew to about 60. At some point, a partition was built so the one-room school could have two classrooms. A few years before integration, students settled into a three-classroom school a block away.

The school was never just a school. Daniels arranged for the dentist to visit. She checked on students at their homes. She took them for picnics on the banks of the Caloosahatchee River, and to the zoo in Sarasota via the train in Fort Myers.

“I called her a pioneer lady,” said alum Brutus Ned, “because she did everything.”

Daniels taught all subjects in all grades until a car wreck in the 1950s left her with medical complications. Even then, she remained active in the community and continued to be a frequent presence at the school.

Its closing in 1966 upset the Black community in LaBelle, just as similar closings upset Black communities around the country. Black teachers lost jobs. Black students felt isolated. The joy they experienced at Daniels School did not follow them to their new schools.

The integrated schools “never had the same feeling,” Johnson said. “The love was missing.”

If Selma Daniels was alive today, she’d have multiple options to create a Daniels School with more resources and more freedom. Students could get state-supported scholarships to attend a private Daniels School. And the day is coming when more flexible scholarships will allow students to access schools in non-traditional settings, like rec centers or churches.

It’s not clear yet if the Daniels School building can be restored. And, if it can be, what will become of it.

Johnson just wants Selma Daniels to get the recognition she is due.

But a new Daniels School, she said, sure has a nice ring to it.