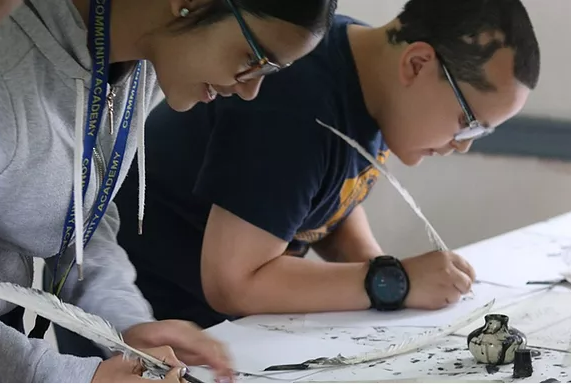

Berkeley Law professors Jack Coons, left, and Stephen Sugarman, circa 1978.

Stephen Dwight Sugarman died the day after Christmas, interrupting almost 60 years of our friendship and collaboration on this planet. His unique character, personality, and family life I will save for another occasion. Here, I will briefly remember his impact on school choice, law school – and myself.

We met in his senior year at Northwestern, academic year 1963-64. I’d like to imagine that I helped lure him to the law school in downtown Chicago. Northwestern had developed a then unique program in law and social services. In any case, he came, and both he and the program prospered.

So did I, as both Steve and classmate Bill Clune, long a Wisconsin professor, spent too much of their second and third years assembling the picture of public school finance systems that led eventually to our persuading the California Supreme Court to hold its state system unconstitutional (Serrano v. Priest, 1971, 1977).

By that time, both Steve and I were on the U.C. Berkeley law faculty where we remained (I in semi-retirement) until his recent higher calling.

Gradually, through the late sixties, we had come to realize that “public” school is anything but what that name implies. The Institute for Governmental Studies published our model for state systems of subsidized parental choice in book form – “Family Choice in Education: A Model for State Voucher Systems.”

In a dozen joint essays thereafter, Steve and I kept trying to explain the catastrophic civil and social effects of a state’s conscription of the un-monied family. In 1978, we put our full message in the volume, “Education by Choice: The Case for Family Control.”

In that year, at the encouragement of Democratic Congressman Leo Ryan, we prepared an amendment to the California Constitution aiming for a popular vote. It was focused upon liberating families of lower incomes.

That year, Leo was murdered in Guiana.

Steve and I – in spite of our political naivete – decided to try it alone. We had expected help from Milton Friedman; instead, the great marketeer inspired a competing, unregulated form that ensured that neither proposition could succeed.

Steve and I tried several times in the early eighties and later and managed to assemble a sufficient coalition of right and center. In his later days, Steve was happy to see the positive relevance of these early failures to most of the “choice” movements of the last few years.

Finally, for the moment: Even in his latter difficult and suffering years, Steve never wavered from his professional role in the academy. He was a much-beloved teacher and a prominent figure in the reform of law of torts, with his own widely praised casebook and many an article striving to make our laws treat the ordinary consumer with fairness and dignity.

Steve finished the fall semester, teaching his last class, a few days before he died. In a very un-Sugarmanic finale, he passed before he could grade his students’ exams. My guess: At higher levels, it had been decided that he deserved a break.

Florida is among those states where where families can participate in private school choice programs at schools such as The Willow School in Vero Beach, where 75% of the students use some form of state-supported school choice scholarship. The result is more diversity than most schools in the region, public or private.

Editor’s note: In this commentary, American Federation for Children chairman Bill Oberndorf explains a state-based strategy for advancing school choice in an interview with Education Next senior editor Paul Peterson. The interview first appeared on the Education Next website.

Paul Peterson: Why did you decide to focus much of your philanthropy on helping disadvantaged children attend private school?

Bill Oberndorf: I felt extremely fortunate that I was able to attend a wonderful private school in Cleveland, and only because my grandparents set aside and saved money for the education of my brothers and me. I felt that every kid who wants to work hard in school, whose parents want something better for them, should have access to the kind of education that best fits the needs of that child. I feel that this is the civil-rights issue of our time.

Peterson: The idea of private-school choice through government-funded vouchers was proposed by Milton Friedman in the 1950s. Seventy years later, we have only a few such programs in this country. Why has it been so difficult to build public support for this idea?

Oberndorf: I remember talking to Milton Friedman about this shortly before he died. He said, “Well, we’re just about right on schedule. It takes decades for ideas to take root before they really can flourish.” So Milton was not deterred. The opposition has come from the teachers unions, which are such a powerful force and funding source for the Democratic Party that this has created major obstacles along the way. But the good news is that now there are private-school choice programs in 22 states. And 45 states plus D.C. have charter-school programs.

Peterson: Yes, but in recent years it seemed like progress was stalling out. In 2016 in Massachusetts, for example, a ballot initiative to expand charter schools was defeated, even though charter schools in Massachusetts seemed to be doing very well. There were also divisions within the school-choice movement, and the energy seemed to be disappearing. How were you assessing the state of school choice at that time?

Oberndorf: The charter-school movement had scaled up to around 3 million students enrolled, and suddenly, for the first time, that sector was feeling the kind of union opposition that the private-school choice movement had felt all along. This did create a lull, but since then, some important things have happened that have helped change the overall trajectory of the advocacy and implementation of private-school and charter-school choice.

To continue reading, click here.

Stephen D. Sugarman, a longtime professor at the University of California Berkeley School of Law and a progressive icon of the education choice movement, died Dec. 26 after a four-year battle with kidney cancer. He was 79.

Stephen D. Sugarman, a longtime professor at the University of California Berkeley School of Law and a progressive icon of the education choice movement, died Dec. 26 after a four-year battle with kidney cancer. He was 79.

News of his death brought tributes from allies in the school choice movement, who saw him and fellow Berkeley law professor John E. (Jack) Coons as groundbreakers for choice and equal opportunity for low-income families.

“He dedicated an enormous amount of time and energy to empowering disadvantaged families with greater access to educational opportunity,” EdChoice policy director Jason Bedrick tweeted. “May his memory be a blessing.”

“Steve Sugarman, along with Jack Coons and Milton Friedman, are the founders of the modern education choice movement,” said Doug Tuthill, president of Step Up For Students, the nonprofit K-12 scholarship funding organization that hosts this blog. “Steve’s ideas about how choice programs should be structured and implemented are still guiding us today. He was a good friend and mentor. I will miss him.”

(To hear a three-part series of Tuthill’s podcasts featuring Professor Sugarman, click here, here, and here.)

A 1967 graduate of Northwestern University School of Law, Professor Sugarman joined the Berkeley law school in 1972 while helping Coons, his mentor, work on school finance issues. Along with William Clune, the pair co-wrote the book “Private Wealth and Public Education” and played a key role in litigating the case that equalized public education funding among California school districts.

Professor Sugarman and Coons teamed up again in 1978 to co-write “Education By Choice: The Case for Family Control.” The book argued in favor of scholarships for students of modest means, as opposed to universal scholarships associated with libertarians, sectarians and segregationists, according to a tribute to Professor Sugarman published by California Law Review.

As Professor Sugarman explained in a 2010 tribute to Coons, the primary goal was “to assure genuine choice to families who are financially disadvantaged, primarily working class and lower-income families.”

According to writings authored by Professor Sugarman’s colleagues to honor his work, the success of today’s school choice movement can be credited to his decades-long perseverance.

“Sugarman has toiled away,” wrote professors Daniel Farber and Mark Gergen.

Berkeley Law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman, circa 1978.

“There were setbacks. He worked against a California referendum creating a school-choice plan that would have hurt non-wealthy families. There were roadblocks. As Sugarman explained in the 2010 tribute to Coons, states’ refusal to allow public funds to be used for religious schooling was a major roadblock to increasing school choices of non-wealthy families. Some of this resistance was based on state laws that prohibited public funds from being used for religious purposes, including religious schools. Sugarman (often working with Coons) designed and advocated for workarounds using devices such as tax credits and scholarships.”

In 2020, Chief Justice John Roberts echoed Professor Sugarman’s writings while rendering a 5-4 decision in Espinoza vs. Montana Department of Revenue.

A “State need not subsidize private education[,] . . . once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious,” Roberts wrote in the majority decision, which sounded similar to Professor Sugarman’s arguments in favor of funding for faith-based charter schools.

Professor Sugarman began teaching at UC Berkeley School of Law in 1972, shortly after he and Coons helped litigate the original Serrano v. Priest school financing case. He served as associate dean from 1980 to 1982 and from 2004 to 2009. His specialty was social justice curriculum, including classes in torts and sports law. Additionally, he was a visiting professor at the London School of Economics, University College, London, and Columbia University.

Last April, his colleagues, family, friends and students gathered virtually to salute his long and illustrious career. At the end of the event, Professor Sugarman gave a salute of his own to those who had gathered to honor him, including his wife of “50 splendid years,” Karen Carlson.

“We law professors at Berkeley Law have the best job I can think of,” he said. “It’s beyond what I could have imagined when I came here.”

Jim and Alice have three children and a modest income. Should their income status justify our forcing these kids into their local assigned public school?

Jim and Alice have three children and a modest income. Should their income status justify our forcing these kids into their local assigned public school?

Are such parents unqualified to choose a school for their own? After all, it is their federal constitutional right to do so.

No doubt some may be less ready than the typical middle-class, college-educated mother and father. But, could it be that a primary cause of any such gap in parental competence is due precisely to our having so long denied them a voice in how, what and where their children shall learn?

My wife, Marylyn, and I had our own share of disappointments with schools, public and private, that we had chosen for our five children; quite naturally we took it as a parents’ responsibility to seek a better way.

We could afford to switch, so we did. In the process, we learned a lot about responsible parenting. We acted and learned by experience.

Are less fortunate parents incapable of the same experience and growth? That was the political decision made long ago in this country.

In the early 19th century, it gradually became apparent to our then Yankee elite that the immigrants “crowding our shores” tended to be unwealthy, unschooled and ideologically alien to “us.” They were different to an extent threatening to the model civic mind then favored by a (mostly) New England elite.

With the genius and eminence of Horace Mann and others, this fear of the un-American immigrant was to spread west and south and the “public” school was born – in a loosely Protestant form – to control this intellectual and spiritual threat.

Mann hoped it would capture and enlighten the succeeding generations of those families who could neither educate at home nor afford to go private.

In spite of the emergence of Jewish and Catholic schools, Mann’s intended mind-set came to dominate the learning of the lower-income, inner-city family until its gradual 20th century overthrow by the new public school emphasis on secularism that dominated our multiplying schools of education; and SCOTUS, in the 1950s, was to exclude religious instruction altogether.

Of course, all that long sway of class-driven school politics always left our better-off families the choice of private school. Why, then, did relatively few of them exercise that option?

In fact, they did.

The tax-supported schools near which they chose to live were never at risk of admitting Jim and Alice’s kids. They were “public” only because Horace Mann and Company had the prudence to choose that label in the 1840s.

It gave their conscription of the poor family the appearance of being democratic, though it was, and remains, anything but.

A family’s access to the public schools of Palo Alto or Beverly Hills is determined by the wealth that makes residence in the district possible. And, as the income class of the individual parents gradually declines below that of the lucky few, their neighbors and their child’s schoolmates will come to match the level of the local residential market.

Thus does “public” school account for much of our segregation by wealthy families. In this inner-city, it reaches the nadir, accounting for the segregation of a substantial percentage of those who can’t afford to leave the neighborhood.

Bad enough. But it also accounts for much of the seeming low quality of these schools whose customers are most unlikely to manage an escape to another attendance area or to win a scholarship to some private school.

Yes, there still are “charters.” For some, their market of hopeful families is substantial; however, the supply is shrinking even in the face of demand. The president (for whom I voted!) with the direction of the teacher unions and their supine state legislators wave their “no-no” for all forms of choice.

Viewing recent political shifts, will Democrats ever begin to recognize that it is their (my) party – not its political enemies – that maintains dominion over the lower-income family, deepening its isolation from both civic participation and personal responsibility over its own precious young kin?

Community Academy of Philadelphia, a charter school launched in 1980, describes itself as a multi-racial, multi-ethnic, and multi-religious family that holds camaraderie and cooperation as essential values.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Lexi Boccuzzi, a University of Pennsylvania sophomore from Stamford, Conn., studying philosophy, politics and economics, appeared Monday on The Daily Pennsylvanian.

The term “school choice” is defined as “a program or policy in which students are given the choice to attend a school other than their district's public school.”

Typically, this results in school districts broadening the types of schools they have, which manifests itself in an expansion of the types of schools available to most students, which often include magnet, charter, or private schools.

While I would imagine this to be a fairly uncontroversial definition, Republicans and Democrats have remained divided on this issue for decades.

In light of increasing conversations surrounding parental involvement in education, school choice issues have grown in national prominence over the past election cycle. As a tutor with the West Philadelphia Tutoring Project, I’ve been able to get a glimpse into the lived experience of Philadelphia public school students. Combined with work on Board of Education races in my own city, it’s caused me to reflect on my own 13 years as a public school student.

These realities, juxtaposed with that of many of my Penn peers who attended private schools, led me to an interesting question: Why should the quality of education your child receives be based on your income?

The School District of Philadelphia poses a unique example on the implementation of school choice policies. In a city with one of the largest school districts in the country, the Philadelphia Board of Education is appointed, rather than elected, creating accusations of little transparency. This poses accountability red flags, making it difficult for parents to express their concerns at the ballot box.

The district also has seen increasing disparity in achievement among racial and socioeconomic groups, with only 32% of children in the third grade meeting the appropriate reading levels.

Philadelphia, unlike many other urban centers throughout the country, also has an expansive charter school system. In Philadelphia, charter schools receive district and state funding while also operating outside various city and state restrictions.

A 2015 report from the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University that looked at urban charter schools found that, in Philadelphia, socioeconomically disadvantaged students at charter schools learned more than their comparable peers at district schools in the city.

To read more, click here.

Editor’s note: To read a comprehensive overview of Coons’ efforts to change the face of education choice, researched and reported by Step Up For Students’ director of policy and public affairs Ron Matus, click here.

Editor’s note: To read a comprehensive overview of Coons’ efforts to change the face of education choice, researched and reported by Step Up For Students’ director of policy and public affairs Ron Matus, click here.

On this special episode, recorded to coincide with the publication of renowned Berkeley law professor Coons’ new book, “School Choice and the Human Good,” he and Tuthill discuss Coons’ more than 50 years of education choice advocacy on behalf of the poor and working classes.

A self-styled liberal from California, Coons and fellow law professor Steven Sugarman crafted a plan in 1978 that would have created more educational options for the parents of 4.5 million California students. As one reporter observed at the time, the plan would have taken a wrecking ball to the old order, installing a new one overnight.

Here’s how a front-page headline in the Los Angeles Times described the plan:

The idea is called school vouchers … this particular form turned out to be too radical even for the 1960s, and it died aborning … Now, however, the voucher idea is alive again, but not just as a theory or a pilot experiment. A statewide initiative is being proposed to make California the first state to establish an entire system of voucher schools, including public, private nonsectarian and religious.

Coons and Tuthill discuss the remarkable twist of fate – the murder of education choice advocate Congressman Leo Ryan in the 1978 Jonestown Massacre – that changed everything. Coons also relates his experience with education icons such as Albert Shanker and Milton Friedman and his unshakable belief that giving less affluent families choice over their children’s education is important for society at large.

“We have got to get the language straightened out. (Education choice supporters) are the liberals. You are opening up democracy for the poor. So long as people yell and scream at you as fascists because you happen to be for choice, let them look in the mirror ...

“It is wrong to fight against (choice) on the grounds that it is a right-wing conspiracy. It's a conspiracy to help ordinary poor people to live their lives with respect.”

EPISODE DETAILS:

Recently, reimaginED executive editor Matt Ladner noted the 10th anniversary of education savings accounts, which debuted in Arizona in the form of the Empowerment Scholarship Account. In the past decade, research has demonstrated a refreshing truth about the accounts.

Recently, reimaginED executive editor Matt Ladner noted the 10th anniversary of education savings accounts, which debuted in Arizona in the form of the Empowerment Scholarship Account. In the past decade, research has demonstrated a refreshing truth about the accounts.

In an age of fake news, they have proved authentic, empowering parents to customize their child’s education, and families are, in fact, doing exactly that.

Data from North Carolina’s two education savings accounts programs find that a larger share of families are using their child’s account to purchase more than one education product or service than those who are only paying for one item, such as private school tuition.

Sixty-four percent of account holders used an account to customize their child’s learning experience in North Carolina’s accounts’ first two years — approximately double the share of Arizona families that customized a student’s experience in the first two years of account availability in that state.

K-12 private school scholarships and vouchers have offered students around the country the opportunity to attend a school of their choice for more than 20 years, bringing hope to children assigned to failing schools. During this period, though, teacher unions and other interest groups have filed lawsuits to force children back into assigned schools, delaying and in some cases erasing these options.

Education savings accounts are not vouchers, and courts have recognized the accounts’ distinguishing feature of allowing parents to choose how and where their children learn, making unions’ charges that the accounts violate state constitutions inaccurate.

(Recent court decisions in favor of scholarships in cases such as Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue also have given parents hope against union lawsuits trying to crush student learning options.)

Thus, the accounts’ flexible provisions and research findings that parents are using these options are significant – both because they allow parents to design a learning experience that meets a child’s needs and because the accounts’ versatility makes them more likely to withstand legal challenges.

North Carolina’s accounts have notable similarities and differences with other account programs, such as the education savings accounts in Florida and Arizona. As with the account laws in other states (Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee, and now Indiana, New Hampshire, and West Virginia), North Carolina state officials deposit a portion of a child’s funds from the state education formula into a private account that parents use to buy education products and services for their children.

Similar to Florida’s accounts, North Carolina’s accounts are available to certain children with special needs. Arizona’s accounts, the oldest accounts in the U.S., are available to children assigned to failing schools, children living on tribal lands, adopted children, as well as children with special needs and other students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Another important similarity that North Carolina’s accounts share with both these state account options is that state officials contracted with private entities to oversee parent transactions. In Florida, most account operations are overseen by private-school scholarship organizations, while in Arizona, lawmakers have hired a payment-processing firm that works in other sectors of public education called ClassWallet.

ClassWallet also is managing much of the account activity in North Carolina, including parent purchases.

State departments of education are not equipped to manage individual family transactions, and state education agencies such as Arizona’s often restricted parent options, resulting in groups such as the Goldwater Institute stepping in to defend families’ rights under the law.

Outsourcing account operations from the inception of North Carolina’s education savings accounts programs saved Tar Heel families the frustration of discovering just how bureaucratic state education agencies can be.

A unique feature of North Carolina’s accounts is that families can combine two private scholarship options, Disabilities Grants and Opportunity Scholarships, with their child’s education savings account. My report for the John Locke Foundation finds that most — 225 out of 277 account holders in 2018-2019, and 216 out of 304 account holders in 2019-2020 — used a Disabilities Grant (a voucher worth up to $8,000 for private school tuition, textbooks, and other qualified items) and an account.

Even with access to both the Disabilities Grant and the account, though, 138 participants still used an account to purchase more than one education item or service.

This research on North Carolina’s accounts offers families and policymakers a glimpse at the future of learning. In just the last year, lawmakers in Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, New Hampshire and West Virginia have enacted new account laws.

How will parents use the accounts, legislators may ask? If data are any guide, they will use them exactly as intended: to meet the unique needs of their children.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Denisha Merriweather, founder of Black Minds Matter and a reimaginED guest blogger, appeared this morning on the Washington Examiner.

Those who say school choice has racist roots are implying that parents, especially lower-income, black parents, should stay trapped in public schools that have failed their children for decades and continue to do so to this day.

To recount the history of racism in the American education system, one must start at the origin of schooling in America.

Why do we prop up the public education system as a symbol of education equity when it was once the primary mechanism for segregation?

Eventually, the federal government decided to provide support for freed blacks through the Freedmen’s Bureau . The bureau’s role was to help transition African Americans from slavery to freedom. It took responsibility for building all-black public schools, converting black independent schools into public schools, supporting existing independent black schools, and funding for volunteer teachers.

The commission of the Freedmen's Bureau was short-lived, but the desire for education freedom never waned. James Forman Jr. states that “in the clearest example of nineteenth-century black 'school choice,' some blacks continued building private schools even after the Freedmen’s Bureau opened publicly supported schools.”

To continue reading, click here.

The White House on Sept. 13 issued an executive order to advance educational equity, excellence and economic opportunity for Hispanics.

The White House on Sept. 13 issued an executive order to advance educational equity, excellence and economic opportunity for Hispanics.

Included in the text of the order is the fact that Hispanic students continue to be underrepresented in advanced courses in math and science, and that they can face language challenges in the classroom. Only 40% of Hispanic children participate in preschool education programs compared to 53 percent of their white peers, so they’re already behind when they start kindergarten.

A lack of creativity in the K-12 traditional education system when it comes to students for whom English is a second language has contributed to poor learning outcomes. Only 19% of Hispanic adults have at least a bachelor's degree compared with 1 in 3 adults overall, and just 6% have completed graduate or professional degree programs compared with 13% of adults overall.

A lack of creativity in the K-12 traditional education system when it comes to students for whom English is a second language has contributed to poor learning outcomes. Only 19% of Hispanic adults have at least a bachelor's degree compared with 1 in 3 adults overall, and just 6% have completed graduate or professional degree programs compared with 13% of adults overall.

While the executive order is a step in the right direction, RealClear Opinion Research polling in fall 2019 showed that when asked if they could select any type of school for their child, 70% of families selected a school other than their zoned public school. Polling from Beck Research conducted in January 2021 showed that 71% of Hispanics either strongly favor or somewhat favor school choice.

Leaders in the education community need to pay attention to what families want, because as the executive order relates, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed many inequalities that already existed among Hispanic students and families. The pandemic opened parents’ eyes, and now. Now more than ever, families not only want school choice; they need it.

The order falls short in that it fails to address ways families can access a school that meets the individual needs of their children if the schools they currently attend fail to do so. If we already know that access to a high-quality education and a fair shot at the American dream is hampered by systematic inequity, I believe we should be looking at how traditional school systems promote these inequities.

We need to give families options and have zero-tolerance for failing district schools in areas with a high population of students of color that have been doing a poor job for generations and failing the same communities this executive order aims to reach.

Let me be clear. The Hispanic community is tired of waiting for the traditional education system to improve and work efficiently. We are tired of being used for anyone's political agenda. Indeed, we would like to see immediate solutions that won't take years to implement. A child gets only one shot at a proper, quality education.

In any ample, subsidized program of parental choice, the student population of public schools in the inner-city will diminish. What, then, will be the effect upon the education in those schools for children whose parents, though now empowered, choose for them to stay put?

In any ample, subsidized program of parental choice, the student population of public schools in the inner-city will diminish. What, then, will be the effect upon the education in those schools for children whose parents, though now empowered, choose for them to stay put?

And second, what eventually will be the effect upon our society of subsidizing these adults to exercise their 14th Amendment right like the rest of us?

Each of these questions deserves a book; the few paragraphs that follow are but an invitation to take both issues seriously. Be forewarned of my own preference and for subsidized choice, at least for our lower-income families. (And note that I will not dwell on test scores, which clearly suffer no harm from parental decision and, rather, appear to improve. In any case, a modest change, up or down, would be scant reason to reject choice.)

The effect upon the mind and spirit of the child

The child of the unmoneyed family who witnesses their deliberation, then selection, of preferred schools will grasp that being a parent is no trivial role among those of our human species. “Here is authority in the very person that I love and with whom I live. In this world about me, family matters at least as much as school; in any case, no school can tell them that I have to go there.”

The child begins to appreciate that grownups, like those in this very family, have a role in the entire adult order of things. “Parents watch the news and worry about their country; they can vote, and this matters for people I don’t even know. Being a parent is a big deal. Maybe I can be one someday.”

Such observations should be no less true of that child whose parents now freely choose to keep him or her in what had been that one specific and unavailable public school. “It’s been a good place for me so far. I’m learning, and I love it. If things go bad, they can always make a switch.”

The mind and spirit of the lower-income parent (LIP)

By LIP, I will here mean those (mostly inner-city) parents with assets and incomes insufficient to (1) move residence and thus qualify for their preferred public school; or (2) pay tuition at a private school of their choice. I’m guessing that these LIPs comprise half our families, though varying widely in degree of financial capacity and thus the need for dollar assistance to choose the child’s school.

Such struggling families were the target of our 19th Century elite who managed to force most LIP children of the inner-city into “public schools,” where they would learn a good deal from selected teachers and the wisdom of the Bible. Horace Mann, that legendary designer and begetter of public school systems, supposed that he was doing a form of Christian ministry by making the King James version a part of the standard curriculum.

Mann’s report in his twelfth and final term as Secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education (1848) stressed his own religious convictions and the urgency of their presentation to all school children:

“In this age of the world … no student of history, or observer of mankind, can be hostile to the precepts and doctrines of the Christian religion … the use of the Bible in schools anywhere … [has] my full concurrence.”

For half a century, Mann’s ideal “non-sectarian” Christian curriculum was to spread and grow. Thereafter, the public school focus began inexorably to shift toward the purely secular. In due course, the Supreme Court was to eliminate prayer and claims of doctrinal reality entirely from the curriculum. At no point along the way did public education ask the opinion of the powerless LIP on matters celestial or even terrestrial.

Nor does it yet, and, in my opinion, with consequent inquiry to the personal and civic roles of those LIPs who conclude, quite reasonably, that the higher ranks of our society consider them incapable of responsible purpose and judgment.

Thus, the parent, like the child, comes to see the institution of family within their social class as feeble, even risky, in the eyes of higher society. “Parenthood for people like us is merely a production line. We make ’em; but it is P.S. 26 that will take ’em and, possibly, wake ’em, to an order of things higher than I could manage. In any case, what’s my choice? Responsibility is not a role for parents like us.”

This, in my view, is no way to build and maintain a democratic society. Even – or especially – assuming that our diverse levels of wealth persist, the poorest of citizens should experience the dignity of being responsible for their own kids, instead of surrendering their minds and spirits to utter strangers.

And with what effect? Horace Mann would, I hope, be profoundly embarrassed at the harvest wrought by our states’ educational culling of their ordinary families. It does assure jobs for their children’s’ mentors, but with what systemic lift for the child?

The effect upon the civic order

Our systemic defining of the LIP family as incompetent to choose embeds itself in the mind of society at all levels. The upper half tends to view the young urban adult as emerging from an inner-city miasma, after 12 years, with a probable deficit in learning, behavior and civic spirit; and I’m not clear that this state of mind is simple prejudice.

But is this the best our democracy can do for these children and for our own national identity?

Sadly, the spirit of Horace Mann yet presides over our children of the street. We want them to become like us but systematically deny them the chance to experience our own middle-class freedom and responsibility.