On this episode, redefinED’s executive editor speaks with longtime education choice advocate Bolick, who is co-founder of the Institute for Justice. Now serving as an associate justice on the Arizona Supreme Court, Bolick recently co-authored Unshackled: Freeing America’s K-12 Education System.

On this episode, redefinED’s executive editor speaks with longtime education choice advocate Bolick, who is co-founder of the Institute for Justice. Now serving as an associate justice on the Arizona Supreme Court, Bolick recently co-authored Unshackled: Freeing America’s K-12 Education System.

Ladner and Bolick discuss the book and imagine what a K-12 education system would look like if it were being built from scratch today. Most traditional schools, Bolick says, are nowhere close to where they need to be if America is to continue its economic prosperity and remain competitive with other developed countries. Education savings accounts, Bolick believes, are the most powerful tool for bringing about improvement in public education.

"We have the ability to deliver a highly personalized, high quality education opportunity to every child in the country today at a fraction of the cost we spend on education. We are so far from that.”

EPISODE DETAILS:

· Bolick’s critique of the current education system and his commonsense principles for creating a 21st century K-12 education system

· Why Bolick believes education savings accounts are the future of public education

· How the COVID-19 pandemic has magnified the achievement gap between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds

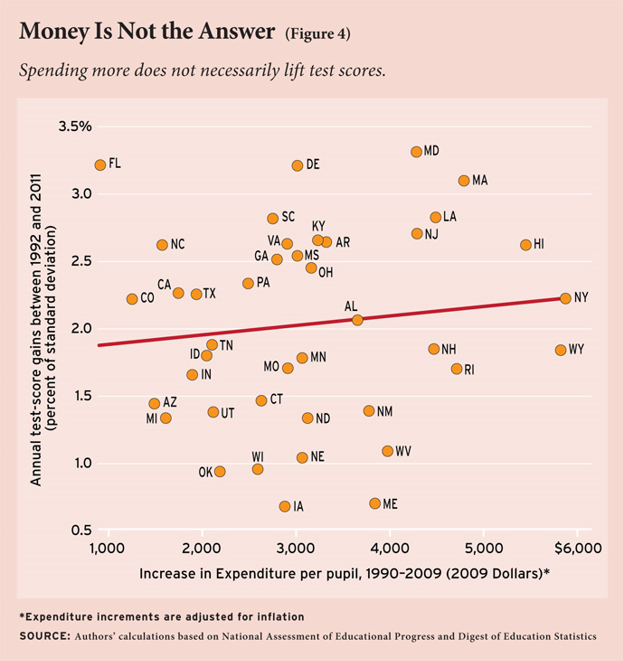

· Test score comparisons to countries spending less on education that belie the fallacy that increased funding can cure America’s educational woes

· How the best teachers can innovate and thrive in a new public education paradigm

LINKS MENTIONED:

RedefinED: Parents, teachers, indicate support for ESAs, national poll finds

Editor’s note: This commentary from Adam Peshek, a senior fellow for education at the Charles Koch Institute, first appeared on Real Clear Education.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Adam Peshek, a senior fellow for education at the Charles Koch Institute, first appeared on Real Clear Education.

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided an unprecedented opportunity to rethink education in America. Instead of hoping for a return to “normal,” let’s learn from what has worked – and what has not – to make lasting improvements and create a more resilient system, one that can adapt to any challenge families may face in the future.

The first step toward realizing a more resilient and family-centered system is to reimagine how we fund education. In short, it’s time to start funding families, not the buildings that are meant to serve them.

Americans spend at least $720 billion on education each year. At around $13,000 per child, that puts the U.S. among the highest-spending countries in the world.

Instead of providing this benefit directly to families – as we do for higher education, childcare, and health care – in K-12, we send this money directly to school buildings. Taxpayer dollars are collected and sent to a central office, and zones are drawn around individual schools where students are required to attend or forfeit the funds raised for their education.

The pandemic has exposed the flaws in this system. School closures, loss of childcare, and difficulties transitioning to online and hybrid-learning models are having devastating effects on children. According to one report, an estimated 3 million students have received no formal education since schools closed in March. That’s the equivalent of every school-aged child in Florida failing to show up for school.

The economic impact on students is estimated at $110 billion in lost future earnings each year. Unsurprisingly, this decline in learning has been felt more deeply by children in low-income families.

These challenges might seem insurmountable, and many of us look forward to the day when we can return to “normal.” But why would we want to return to a status quo that has proven a failure during a time of crisis? While we may not encounter an international crisis of the scope and scale of COVID-19, families face immeasurable local and personal crises each year.

This is a time to learn from innovations that have proven successful and integrate them into the system moving forward.

One of the biggest innovations during the pandemic has been the proliferation of individualized education. Families with resources – financial and otherwise – are taking matters into their own hands. They are hiring tutors, forming learning pods, enrolling in microschools, sharing childcare, reimagining after-school programs, and rearranging their lives to provide the continued learning opportunities that many children have lacked for months.

These unconventional models may yield academic benefits. Researchers from Opportunity Insights analyzed data from 800,000 students enrolled in an online math curriculum used by schools before and during the pandemic. The researchers found that students in low-income neighborhoods saw a 9% decline in math progression between January and April. Meanwhile, students from wealthy ZIP codes saw a 40% improvement over the same period.

In other words: in the spring, with schools closed during the pandemic, students in some wealthy families may have progressed academically at higher rates than if the schools had remained open.

This is raising understandable equity concerns from advocates concerned about widening gaps between low- and high-income students. But in a situation where some students are progressing and others are falling behind, the solution isn’t to move everyone to the middle. It’s to give those falling behind access to the same type of learning that is allowing others to thrive.

The sort of family-directed, individualized education taking place during the pandemic is likely to expand its presence in American life. As an Atlantic article observed, “COVID-19 is a catalyst for families who were already skeptical of the traditional school system – and are now thinking about leaving it for good.”

The author of that piece, Emma Green, recently said in an interview that home-based, unconventional methods of education are getting “a flood of interest from parents of all kinds.” Early data seems to confirm this, with large upticks in families opting out of school systems to pursue homeschooling.

To create a more effective and more resilient education system, we must learn from what has proven effective during the pandemic – namely, the ability of those with resources to identify and pursue a variety of individualized learning opportunities to meet children’s needs. To provide these same opportunities for all families, governments should prioritize direct grants to families, education spending accounts, refundable tax credits, and myriad other ways to get money into the hands of families so they can build an education that fits their needs.

The way in which we currently fund education is blocking equal access to these learning opportunities. To expand that access, we need to fund families, not school buildings.

Official reports of public school budgets and spending seldom have been easy for the common taxpayer, like myself, to understand whether such disclosures come from state, district or individual school – and, whether the numbers that actually are reported for expenditures are those for non-teaching personnel, sub-categories of pupils, or for equipment, repairs and security, they rarely are easy for the common reader to understand.

The official reporting accountant often lacks incentive to parade the employer’s relative wealth, federal and/or private charity. Thus, when we hear that the District of Superport spends $15,000 per child, while a bordering district spends half again that amount, this doesn’t tell us a lot until we learn more about what these respective districts included in their calculation.

When co-authors and I were writing “Private Wealth and Public Education” in the 1960s, we found that states, districts, individual schools and, in turn, the media, often were not telling it all, whether by design or innocence. Some were silent about debt or the interest paid on it, and often the costs of discharging or sidelining unperforming teachers; the same often was true with respect to income such as federal aid, gifts from private donors, rents received and the like.

Very often, no clear legal standard of reporting bound ether state or district authorities. As our research proceeded, it became plain that folks responsible for composing the “public” message sometimes were serving purposes of their own.

Fifty years later, spies tell me that things have changed but a little; more than one reliable expert friend who has some window on the California system has been unable with confidence to estimate the actual overall per-pupil cost to the taxpayer. The public system, to a considerable degree, operates as if it were part of that private market in which competing schools often prefer to remain inscrutable on the subject of resources and budget.

What is clear about the numbers of the public sector is the steady half-century swell in our expenditure per child and the overall enhancement of spending for non-teacher personnel. The latter now represents something over half the budget in most corners of our society. That this shocks me is, I suppose, the effect of its radical difference from my own childhood experience.

I hereby concede that today’s reality is not necessarily bad; those assistant principals, librarians, nurses, bus drivers, coaches, janitors and security may be necessary, and even a blessing.

In any case, this shift in economic focus is a reality of which taxpayers should be aware. The traditional public school has become increasingly expensive even as it has consistently failed to graduate better educated kids. That happier outcome has been left to parentally chosen charter schools which have shown themselves able to teach more at a smaller cost per-pupil to the taxpayer. Some do so even while turning a profit.

Again, I am not suggesting any unlawful behavior nor pushing away a formula for setting the best level of spending for any specific purpose or for total investment per pupil. I pray only that one day the media will be given – then report in an intelligible manner – a clearer picture of just where the dollars went. While grossly overstating the problem, English humorist, novelist, playwright and law reform activist Sir Alan Herbert showed the effect on many a frustrated taxpayer:

Fancy giving money to the Government

Nobody will see the stuff again!

-- Herbert, Too Much!

Whether too much, too little, or just the right sum, there are many among us who would like the chance to see that the “stuff” got to its assigned place and is performing its assigned task.

Abundant Life Christian Academy in Broward County is among several Florida private schools that will begin receiving federal relief funds through the Paycheck Protection Program.

Federal relief funds are starting to trickle in toward private schools, offering at least some short-term relief to a sector that is likely to be hard hit by the coming economic slump.

The aid is through the Paycheck Protection Program, a $349 billion slice of the $2 trillion relief package that’s aimed at helping American workers and businesses stay afloat in the wake of the pandemic.

The PPP offers forgivable loans to small businesses and nonprofits with fewer than 500 employees, including private schools and charter schools. The loan amount is up to 250 percent of an employer’s average monthly payroll, with a $10 million cap. If the employer maintains that payroll for eight weeks, the loan is forgiven. The loans can also be used for interest on mortgages, rent and utilities.

Small businesses and nonprofits began applying for the PPP loans April 3. This week, some private schools began receiving approval notices from their banks.

In Broward County, Fla., the church affiliated with Abundant Life Christian Academy applied for a PPP loan for both it and the school, said principal Stacy Angier. On Monday, it got word the school would receive $320,000 to help pay its 50 employees and continue serving its 462 students. Angier was hopeful the funds would be in hand next week.

“It’s huge. No. 1, because it helps to carry payroll and keep staff members working right now. But also because we will have to carry payroll beyond the normal time frame for the school year,” Angier said. “I have some students who are going to need extra support this summer to be ready for the fall. We have some that are challenged by this online learning platform, particularly those with special needs.”

Angier said revenues were already down “significantly,” even with 80 percent of Abundant Life students using some type of state school choice scholarship. Growing numbers of parents are being laid off and can no longer afford the gap between tuition and scholarship. But Angier told them they would find a way.

Once the PPP opened up, thousands of small businesses flooded banks with a “tsunami of applications.” In some states, private school groups worked hard ahead of time to notify as many private schools as possible that they, too, were eligible (see here, here and here).

Florida is home to one of the biggest private school sectors in America, with nearly 2,700 private schools serving 380,295 students. More than 2,000 of those schools participate in a variety of education choice scholarship programs that together serve more than 160,000 students in K-12. (Another 130,000 students use state funds to attend private pre-schools.)

The largest of those choice programs, the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, serves about 100,000 students. The Gardiner Scholarship, the nation’s largest education scholarship account program, serves another 13,000. Both are administered by nonprofits such as Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.

It’s not clear yet how many private schools in Florida applied for the PPP. More than a dozen contacted by Step Up representatives this week said they had; most were still awaiting word on approval.

HOPE Ranch Learning Academy was among those that got good news. It will be receiving $261,000.

“During this time of uncertainty, the PPP program's most valuable help is to secure income protection for all of our staff so when we get clearance to return to work, we can do so immediately with our entire staff and not lose some in the process,” Jose Suarez, the school’s founder and executive director, said in an email.

Josh Longenecker, founder and headmaster of The Classical Academy of Sarasota, said his school applied for the loan April 8 – and got approval five days later. It’s set to receive $280,000 to help cover expenses for 47 employees serving 365 students. “It’s a huge help because we don’t know what the future will hold,” Longenecker said. Besides current expenses, the money “will also provide us with a backup plan if enrollment doesn’t pick up in the fall.”

Through Monday, banks had processed nearly 900,000 PPP loans worth $215 billion, including 52,000 in Florida. By some predictions, PPP funds may be gone by the end of this week, but talks are underway for a second round, with a pitch from Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin for $250 billion.

Suarez had advice for private schools that had yet to apply: Don’t wait.

“The application process was unbelievably easy to complete,” he said. “However, it does require historical data from 2019 payroll. A school that does not have clear wage, benefit, and payroll tax breakout will have difficulty in completing the application.”

It’s possible private schools may get relief from other funding streams in the CARES Act.

On Tuesday, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos announced $3 billion in block grants from the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund would be quickly distributed to states, with Florida’s cut at $173 million. DeVos stressed flexibility with the funding, suggested it be applied to distance learning needs, and included charter schools and private schools in the mix. Florida education officials have yet to offer details.

With the presidential primary election in delegate-rich Florida just two months away, Democratic candidates are beginning to knock on the door.

With the presidential primary election in delegate-rich Florida just two months away, Democratic candidates are beginning to knock on the door.

In a Monday column in the South Florida Sun-Sentinel, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders found little to like about Florida’s public education system. But our focus is on educational choice and three assertions he made while insisting that “Florida is ground zero of a school privatization movement intent on destroying public education.”

“Each year almost $1 billion in state money goes to private schools instead of public schools.”

“These private schools operate with little to no accountability.”

“In many cases, their students’ math and reading skills have declined.”

These claims are misleading, at best.

Claim No. 1: The $1 billion citation draws attention but does not prove Sanders’ point. He implies that private school voucher and scholarship programs harm public schools financially, which is a longstanding and erroneous argument advanced by the Florida Education Association (FEA) that we have dealt with previously in this space. There is simply no evidence to support it.

Eight different independent financial studies all have concluded the scholarships, which cost less per student than the total amount spent in a traditional public school, save tax money that can be used to enhance public schools. Florida TaxWatch weighed in last year, finding existing scholarships cost 60 cents on the public school dollar. And the FEA lost its legal challenge to the 19-year-old Tax Credit Scholarship program in part because the trial and appellate courts summarily rejected its argument that public schools “have been and will continue to be injured by the scholarship program’s diversion of resources from the public schools.”

Claim No. 2: The qualifier in this assertion – that private schools operate with “little to no” accountability – gives Sanders some wiggle room in part because accountability is hard to objectively measure. But Sanders seems to dismiss entirely the accountability that is inherent with any school that survives only if parents choose it for their children.

That market concept may not appeal to a self-professed socialist but does have real-world consequences and, in the case of the state’s two scholarships for underprivileged students, gives genuine educational power to parents who typically have little.

As to the regulatory oversight, Florida’s largest program, the Tax Credit Scholarship serving 108,570 economically disadvantaged students this year, is ranked among the nation’s most aggressive. The students, schools and scholarship organizations are subject to roughly 17,000 words of statutory and agency regulations.

Among those requirements: scholarship students must take state-approved standardized tests; those test results are reported publicly every year; schools must submit annual financial reports by certified public accountants; and scholarship organizations must be audited each year by the state Auditor General and independent accounting firms.

Sanders is entitled to believe the program is not subject to sufficient regulation, but we rate his claim of “little to no” accountability as misleading.

Claim No. 3: Once again, Sanders uses an interesting qualifier – “in many cases” – in his assertion that scholarship students’ “math and reading skills have declined.” Eleven years’ worth of standardized test reports refute his claim.

Students who receive the Tax Credit Scholarship must take a nationally norm-referenced test each year approved by the state, and most take the Stanford Achievement. The test scores are sent to Florida State University’s Learning Systems Institute, which is paid to aggregate and report them publicly.

For the most recent year, 2017-18, scholarship students scored on average at the 47.4 percentile in reading and 45.2 percentile in math. That’s basically average, which is encouraging given that these scholarships students are among the poorest in the state and were among the lowest-performing students in the public schools they left behind.

More to the point, their annual gains have been remarkably consistent. The scores reflect that these low-income students have achieved the same annual gains as students of all income levels nationally.

In other words, they have increased, not declined.

Certainly the average doesn’t reflect every student. In the most recent report, about as many students – 0.6 percent – achieved extraordinary gains of more than 40 percentile points as those who dropped an equivalent amount. But Sanders’ qualifier that “many” students declined seems intended to distort the overall test findings. We rate it mostly false.

A rendering of California’s Piedmont Unified School District's new, $66 million STEAM building. The affluent district raises thousands more for each student in local property tax than nearby mostly not-rich and not-white Oakland.

Higher education writer and policy analyst Kevin Carey turned in a stirring indictment of school districts as instruments of racial and economic segregation in the quarterly journal Democracy. Carey drinks a different flavor of ideological tea than my preferred flavor, but as jeremiads go, this one is well worth reading. Carey’s delve into the dissents delivered by Justice Thurgood Marshall in the Edgewood and Milliken decisions are especially poignant. Marshall, the attorney in the Brown vs. Board of Education case, dissented furiously as the Supreme Court demurred from further action to equalize funding or consolidate districts for purposes of integration:

Marshall saw the future clearly. “School district lines, however innocently drawn, will surely be perceived as fences to separate the races,” he wrote. “In the short run, it may seem to be the easier course to allow our great metropolitan areas to be divided up each into two cities—one white, the other black—but it is a course, I predict, our people will ultimately regret.”

Everything Thurgood Marshall feared came true. Detroit Public Schools have been perpetually wracked by crisis and decay. The wealth disparity along the Grosse Pointe border is so stark you can see it through Google’s satellite images—on one side of Alter Road, dense and prosperous neighborhoods, on the other, hundreds of vacant lots. Meanwhile, in San Antonio, the Alamo Heights school district today receives more than $19,000 per student in state and local funds. Most of its students are white. Edgewood, still alone, gets less than $10,000. Ninety-seven percent of its students are Hispanic. The bigots who wrote the restrictive covenants into Alamo Heights property deeds all those decades ago were fighting a war for power and opportunity in the coming century. They won.

This history recalls the tragedy of Reconstruction in the old South and Plessy vs. Ferguson. Plessy’s “separate but equal” quickly turned very separate but entirely unequal. The North’s failure to prevent the South from replacing slavery with Jim Crow and sharecropping was a horrible betrayal of the sacrifices made during the war and of America’s ideals. White southerners lost the war but subverted the peace through exhaustion-inducing asymmetrical tactics. They lived in the South after all; the North, they reasoned (correctly), would not be capable of occupying their states forever. Decades later, in 1896, the Supreme Court faced the dilemma of following the clear intent of the Constitution, or alternatively issuing an order that the North had little stomach to enforce.

The court blinked, creating a repugnant “separate but equal” standard that would stand for decades until Brown vs. Board. Only a single Justice delivered a (blistering) dissent to separate but equal:

But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved. ... In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott case.

Caste however is precisely the problem that Carey describes today. Americans buy their way into school boundaries with effective schools. Suburbanites have deep reservoirs of social, political and financial capital, and they have leveraged themselves heavily to purchase homes on the desirable side of district boundaries. District advocates possessed of a certain level of naivete often argue that “district schools take everyone.” The reality, of course, is quite different: District schools take everyone who can afford to live within their attendance boundary. Those who have paid the toll have a gigantic vested interest in the maintenance of the status-quo in the form of both access to the highest performing schools and with regards to property values.

One of Carey’s proposed solutions to promote school integration is to redistrict school districts in a way similar to those of legislative and Congressional districts. This would be an entirely admirable proposal if one’s purpose were to spur a nationwide political bloodbath every 10 years. For instance, the Maryland suburbs surrounding Washington, D.C., have a reputation as a progressive stronghold, but when a district there proposed redistricting, the community went to Defcon 5. If you want to stare into the abyss, read this article and imagine this happening everywhere every 10 years.

Fortunately, we have a different strategy available to us, and we’ve been pursuing a different strategy – creating school options where access is delightfully independent of the zip code in which the child lives: magnet schools, charter schools, private choice programs and home schooling. Public K-12 funding is safely enshrined in state constitutions, enjoys overwhelming public support, and won’t be going anywhere. Zip code assignment to schools, however, is a practice which does not merit anyone’s support. A frontal assault on purchased privilege may seem tempting but is as doomed to failure as the well-meaning efforts of the American Reconstruction.

If we look at the world as having a fixed sum of desirable schools, we should not be surprised if the wealthy hoard access to them. They already have this access, and they won’t willingly surrender it. They constitute an incredibly powerful bipartisan community of self-interest. If we expand the supply of desirable schools and thus weaken the link between zip code and schooling, and if we give communities of all types more options to specialized schooling, we have a chance.

We should not view an ideal school system as a forever war over finite seats in desirable schools. Rather, we should aim to create a liberal system of education giving educators the freedom to create education opportunities and families the flexibility to select between them based upon the interests and needs of the students – with meaningful levels of assistance for disadvantaged students.

The Urban Institute has released a study of long-term outcomes associated with private choice program participation in Florida, Wisconsin and Washington, D.C., tracking college attendance and college completion rates for choice participants for the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program, the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program and the Washington, D.C., Opportunity Scholarship Program.

The Urban Institute has released a study of long-term outcomes associated with private choice program participation in Florida, Wisconsin and Washington, D.C., tracking college attendance and college completion rates for choice participants for the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program, the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program and the Washington, D.C., Opportunity Scholarship Program.

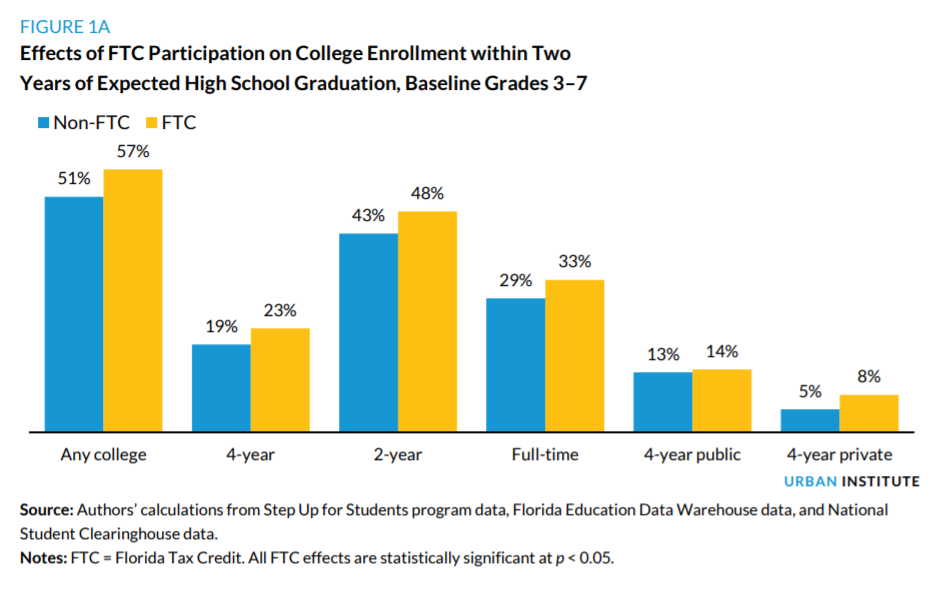

Digging deeper: The results show clear advantages for choice students in Florida. Fifty-seven percent of Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students who started the program between third and seventh grades enrolled in college compared with 51 percent of matched non-Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students. Additionally, Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students had higher college-going rates in all sectors and were more likely to attend college full time. The Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program’s impact on both enrollment and degree attainment grew with the number of years of program participation.

Digging deeper: The results show clear advantages for choice students in Florida. Fifty-seven percent of Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students who started the program between third and seventh grades enrolled in college compared with 51 percent of matched non-Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students. Additionally, Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students had higher college-going rates in all sectors and were more likely to attend college full time. The Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program’s impact on both enrollment and degree attainment grew with the number of years of program participation.

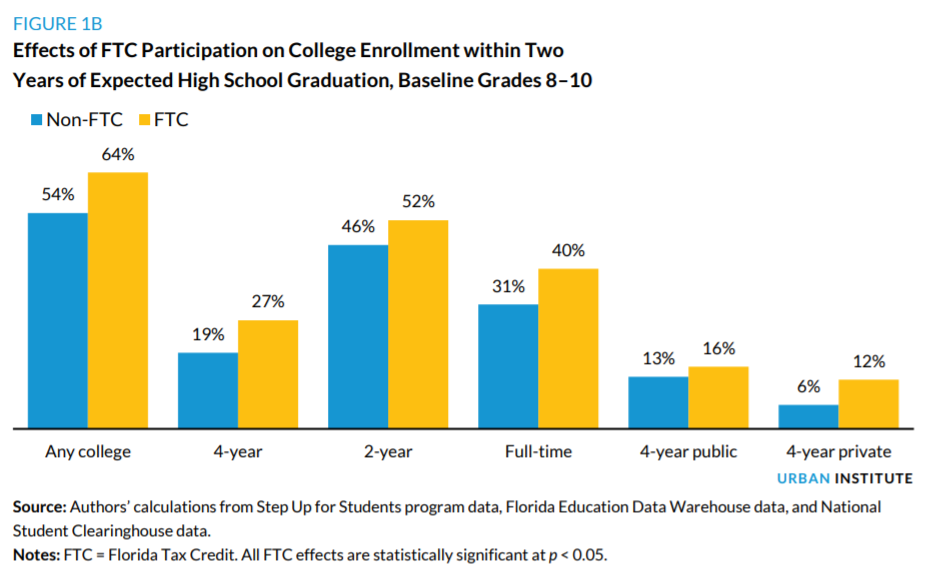

A similar pattern emerges in the data for students starting in the program between eighth and 10th grades. Sixty-four percent of Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students attended a college within two years of their expected graduation rate, while the rate for the comparison group was 54 percent.

A similar pattern emerges in the data for students starting in the program between eighth and 10th grades. Sixty-four percent of Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students attended a college within two years of their expected graduation rate, while the rate for the comparison group was 54 percent.

The study found positive results among scholarship program students in Wisconsin and neutral findings in Washington, D.C.

The big picture: The Urban Institute study results show better long-term student outcomes at a lower per-pupil cost in Florida and Wisconsin and equivalent long-term outcomes at a much lower per-pupil cost in Washington, D.C.

· The average Florida Tax Credit Scholarship amounts to 69 percent of the state’s average total per-pupil spending in the public school system.

· In Wisconsin, the MPCP average scholarship amounted to 67 percent of the average district per-pupil spending.

· In Washington, D.C., the average Opportunity Scholarship amounted to only 46 percent of the average per-pupil spending in District of Columbia Public Schools.

In Florida, Wisconsin and the District of Columbia, the Urban Institute analysis finds, respectively, better, better, and the same long-term outcomes.

The takeaway: Imagine the possibilities if the students in these programs received equal funding and enjoyed the flexibility of spending funds on enrichment activities such as tutoring and summer camps in addition to private school tuition.

Johns Hopkins University’s School of Education on Wednesday released a 93-page report of the Providence, Rhode Island, Public School District that provides a useful cautionary tale on how not to structure a K-12 system, reminding us that big spending and strong unions fail to produce learning for kids.

Johns Hopkins University’s School of Education on Wednesday released a 93-page report of the Providence, Rhode Island, Public School District that provides a useful cautionary tale on how not to structure a K-12 system, reminding us that big spending and strong unions fail to produce learning for kids.

Among the report’s highlights:

· The great majority of students are not learning on, or even near, grade level.

· With rare exception, teachers are demoralized and feel unsupported.

· Most parents feel shut out of their children’s education.

· Principals find it very difficult to demonstrate leadership.

· Many school buildings are deteriorating across the city, and some are even dangerous to students’ and teachers’ wellbeing.

You can view local television coverage of the “devastating” report here and here.

Meanwhile, the Digest of Education Statistics shows that Rhode Island spent a total of $16,496 per pupil in the 2014-15 school year compared to Florida’s per-pupil expenditure of $9,962.

The John Hopkins researchers visited multiple Providence classrooms and found reading classes where no one was reading and French classes where no one was speaking French. They did, however, observe kindergarten students punching each other in the face, students staring at their phones during class, and students communicating over Facetime during class. One can only shudder to think what might be going on when university researchers aren’t touring the school.

Twenty-five kids in a Providence classroom will generate a bit over $400,000 in revenue. That money gets spent on something, but alas, there isn’t much learning happening.

Now at this point in the conversation, some of our friends with reactionary traditionalist K-12 preferences often trot out the litany of poverty in the district. We can’t expect kids to avoid Face-timing in class overcome the burdens of poverty until X, Y or Z is done. Well, all states have low-income kids, so how does the academic performance of low-income students in Rhode Island compare to those in other states?

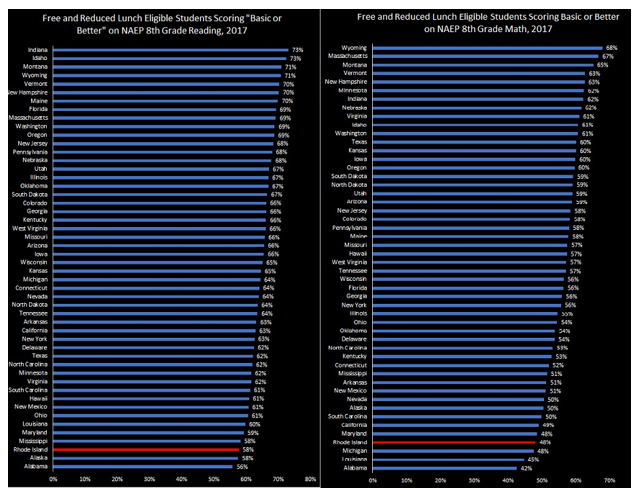

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores strongly reinforce the findings of the Johns Hopkins researchers. For those of you squinting at your iPhone, that is Reading on the left, Math on the right. The percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch who scored “basic or better” is shown on both charts.

These results are nothing less than sickening for Rhode Island, given the gigantic taxpayer investment in the system. Mississippi beats Rhode Island on both tests, and Rhode Island’s poor children score much closer to poor children in Alabama than they do to poor children in neighboring Massachusetts.

Florida is the only state with a majority minority student population to crack the Top 10 in either Reading or Math in 2017. It is unfortunate that a vocal minority in Florida seems desperate to kill the policies leading to that improvement, and hell-bent on adopting a policy mix closer to that of Rhode Island.

Decades of cross-sectional research shows a weak relationship between K-12 spending and academic outcomes. During the Jeb Bush era in Florida, for instance, we saw the following outcomes:

Decades of cross-sectional research shows a weak relationship between K-12 spending and academic outcomes. During the Jeb Bush era in Florida, for instance, we saw the following outcomes:

For those squinting at your iPhone, that’s a very weak relationship between state spending increases and academic gains. While Florida had the smallest increase in funding, it was among states with the largest academic gains. Wyoming and New York had spending increases six times greater than Florida, but posted much smaller academic gains.

Digging deeper: We’ve seen reporting recently that claims the existence of a much stronger relationship between spending and outcomes. There is this piece, for example, in The Economist. But like a lot of research, it rests upon questionable methodological assumptions. Which are you going to believe: academic assumptions regarding the exogenous nature of court-ordered funding increases, or your own lying eyes (refer again to the chart above)?

· Following the period covered in the chart, Arizona led the nation in academic gains as measured by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) while suffering through some of the nation’s largest Great Recession-induced cuts in K-12 spending.

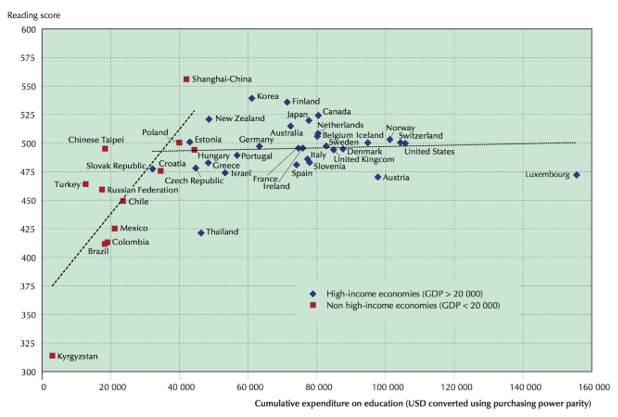

· The mantra that “money doesn’t matter” also seems over-simplified when examining the international data. It does take money to run a school after all.

Taking things one step further: The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) published this graphic plotting national averages on spending and how students in both developing and economically advanced nations fared on the Program for International Student Assessment, an international test that every three years measures reading, mathematics and science literacy of 15-year-olds:

Breaking it down: Developing nations show a strong positive relationship between higher levels of spending and higher reading scores. Once countries pass a certain threshold of expenditure, however, the relationship becomes much weaker.

· You can combine these two charts with the understanding that all American states would be past the global point of diminishing marginal utility (the United States is the second highest spending country in the OECD chart).

· In other words, throwing money at American school districts and hoping for the best remains a poor strategy for improving K-12 outcomes. In the end, this largely is a moot point; unless states get control of their health care budgets, they likely will lack money to throw.

Conclusion: State policymakers should focus their efforts on increasing the bang for the education buck regardless of spending level. If increasing spending had a large positive impact on student achievement in the American K-12 system, our African American and Hispanic students would not be posting scores closer to the average scores of students in Chile and Mexico; their scores would be more in line with European, Asian and white American students.

To read more on the topic of education spending, click here.

‘When I was arrested, Oceania was at war with Eastasia. With Eastasia. Good. And Oceania has always been at war with Eastasia, has it not?’

Winston drew in his breath. He opened his mouth to speak and then did not speak. He could not take his eyes away from the dial.

‘The truth, please, Winston. YOUR truth. Tell me what you think you remember.’

‘I remember that until only a week before I was arrested, we were not at war with Eastasia at all. We were in alliance with them. The war was against Eurasia. That had lasted for four years. Before that——’

O’Brien stopped him with a movement of the hand.

-George Orwell, 1984

Oceania’s totalitarian government in Orwell’s 1984 relied on a daily “Two Minutes Hate” to whip people into a frenzy against enemies of the state. As Wikipedia helpfully explains:

Within the book, the purpose of the Two Minutes Hate is said to satisfy the citizens’ subdued feelings of angst and hatred from leading such a wretched, controlled existence. By re-directing these subconscious feelings away from the Oceanian government and toward external enemies (which may not even exist), the Party minimizes subversive thought and behaviour.

If you’ve read the newspaper recently you might think you were living in Oceania, but with the new Family Empowerment Scholarship program serving in the role of the hated enemy of the people instead of Emmanuel Goldstein. I could site any number of examples, but the Tampa Bay Times takes the cake for hyperbolic excess with Death Sentence for Florida Public Schools:

They approved the death sentence for public education in Florida at 1:20 p.m. Tuesday. Then they cheered and hugged each other. The legislation approved by the Florida House and sent to the governor will steal $130 million in tax money that could be spent improving public schools next year and spend it on tuition vouchers at private schools. Never mind the Florida Constitution. Never mind the 2.8 million students left in under-funded, overwhelmed public schools.

The Orlando Sentinel, however, reported the following on the 2020 Florida budget:

In the spending outline, K-12 schools funding landed at $21.8 billion, a $782.9 million increase on the current year, or nearly 4 percent.

Thus, Florida lawmakers signed a “death sentence” for Florida public schools by increasing their funding by almost $800 million. First world problem, anyone? According to my Excel spreadsheet, if the Florida Legislature had diverted the entire appropriation to the public school budget, it would have increased spending by 1 percent.

To the Times’ credit, they did provide former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush an opportunity to respond. Bush helpfully noted that Florida does not have a fixed student body but, rather, is rapidly growing:

The Times assumes that because a child chooses to attend a private school of their choice that public schools will somehow be harmed financially. But according to Florida’s Office of Economic Demographic and Research, over the next four years public school enrollment in Florida is projected to grow by an additional 94,000 students — one of the fastest growth rates in the nation.

The Family Empowerment Scholarship program is capped at around 46,000 students during that same time frame. So where exactly is the harm?

Where indeed? The Florida Department of Education provides a spreadsheet that shows Florida school districts spent almost $863 million in 2017 and created spaces for 30,323 students in the process. Call me crazy (it’s been too long since anyone has been good enough to do so) but it appears to me that the new scholarship program will relieve the pressure on Florida districts, whose enrollment will continue to increase. Funds you don’t have to spend on debt service can be used for other purposes – such as paying teachers.

In addition to electronic surveillance, thought police and 2-minute hates, constantly being at war constituted another trick up Oceania’s totalitarian sleeve. Twenty years have passed since the first Florida private choice program passed; Florida’s academic outcomes have improved all the while.

Ignorance of these facts is not strength, and freedom is not slavery. Florida editorial boards are at war with the right of Florida families to exercise autonomy in education. Will Florida editorial boards always be at war with Florida families?