When Florida lawmakers debated HB 1 earlier this year, the discussion largely focused on how the legislation would dramatically expand education choice through universal eligibility and flexible spending options for families.

Another part of the bill inspired far less discussion but got the attention of school district leaders across the state: a review of public school regulations.

By Nov. 1, the state Board of Education must develop and recommend “potential repeals and revisions” to the state’s education code “to reduce regulation of public schools.”

“This is a great step towards keeping our public schools competitive” in an era of expanded options, said Bill Montford, a former Democratic state Senator from North Florida who heads the Florida Association of District School Superintendents.

“Traditional, neighborhood public schools have been, and will continue to be, the backbone of our K12 education system,” he

Bill Montford

said. “We want our schools to be the first choice for parents, not the default choice, and to do that we need to reduce some of the outdated, unnecessary, and quite frankly, burdensome regulations that public schools have to abide by,”

Before they propose any changes, state board members must consider feedback from a diverse group that includes teachers, superintendents, administrators, school boards, public and private post-secondary institutions and home educators.

To fulfill that requirement, board members set up a survey link that will accept suggestions through today. A group of superintendents submitted a recommendation list that covers topics that include construction costs, budgets, enrollment, school choice, instructional delivery and accountability. Their pitches included proposals to:

"We’d like for them to recognize all parental choice equally and give school districts the same flexibility and opportunity to innovate provided to other publicly funded options,” said Brian Moore, general counsel for the superintendents association that Montford leads. He added that the superintendents would like to see more cooperation between school districts and the Department of Education.

This effort isn’t the first the state has made to provide school districts with relief from what they see as burdensome regulations. But to some leaders the process seems more like a game of Whac-A-Mole, with new regulations soon replacing the ones that get repealed.

Ten years ago, Gov. Rick Scott signed SB 1096, which repealed some regulations based on the recommendations of a group of superintendents, including Montford. The bill repealed a requirement approved in 2010 that all public schools and universities gather and report statistics showing how much material each had recycled during the year. It also ended a 2002 requirement that schools submit plans for teaching foreign languages to kindergarteners.

Other efforts to ease the regulatory burden have targeted schools that meet certain conditions. Since 2017, schools with strong test scores and consistently high letter grades could be qualified as “Schools of Excellence,” which grants their leaders more flexibility.

Moore said he hopes things work out this time around, but said the key is allowing changes to apply across the board, not to certain schools or districts, and to carefully consider future regulations and their potential effects.

Christina Sheffield’s son, Graham, was soaring ahead of classmates. She wanted a learning environment that challenged him, so she created one herself.

She pulled him out of a private school and created a customized education plan. Using her know-how as a certified elementary virtual school teacher, she enrolled him in a hybrid homeschool co-op and designed projects to enhance the curriculum his former private school as using.

But there was a missing piece in her son's custom education plan: Their neighborhood public school.

That changed when the Tampa Bay area mom received the results of her son’s test for academic giftedness. Now officially identified, Graham, like other gifted homeschoolers, was able to access services offered by his local school district. He started going to a weekly gifted class at his zoned elementary school.

“It was his favorite day of the week,” Sheffield recalled. “After I picked him up on the first day, he said, ‘Mom, I finally feel like I fit in.’ That made my mom’s heart happy.”

Other students in similar circumstances might not be so lucky. Florida law allows homeschoolers to enroll in dual enrollment classes that lead to college credit, free of charge. Students participating in the state's growing array of educational choice options have access to extracurriculars at their local public schools under the state's "Tim Tebow law." But that same guaranteed access does not extend to math class.

Districts can offer homeschoolers access to career and technical courses, or services for exceptional students, included gifted programming for students like Graham. And a new law allows districts to receive proportional funding for any student who chooses to enroll part-time while participating in other educational options.

But they are not required to offer this opportunity.

A new analysis by the advocacy group yes.everykid. evaluated policies in all 50 states and found that states vary widely in policies that grant students access to their local public schools, regardless of where they live or whether they want to enroll full-time.

Florida's policies place it in the top 10 among states, but it has not yet guaranteed that every student has the right to access public schools on their terms.

Among the findings:

Florida tied with Alaska for ninth place when it came to allowing nonpublic and homeschool students access to public schools. Idaho, which met every criterion used in the rankings, was No. 1, followed by Iowa and Minnesota, which tied for second place.

Though HB 1 codified the option for Florida public school districts to offer part-time enrollment options and receive prorated state funding, it left the decision whether to participate up to the individual districts.

Districts may be reluctant to embrace this new flexibility, and some state policies make this understandable. For example, state class size limits may add to the staffing headaches for districts hoping to accommodate students who enroll part-time.

The new law also creates a process for districts to identify regulatory barriers that are preventing them from responding to the needs of students and families.

For decades, some districts have resisted the oncoming tsunami of new education options. Others have chosen to ride it, and now have new flexibility at their disposal. The question is whether they will capitalize on that flexibility to meet the needs of their students.

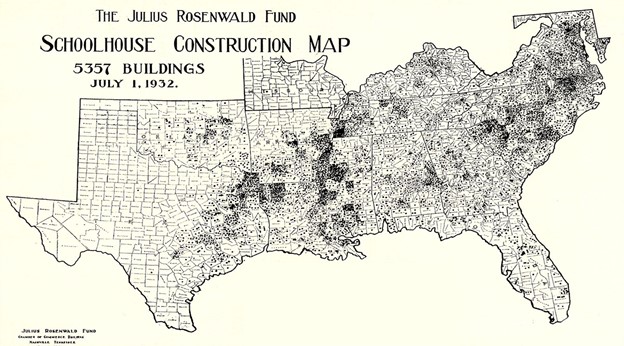

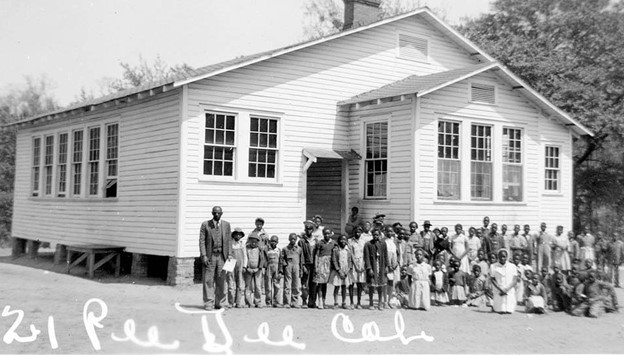

Rosenwald schools served as a forerunner of the modern choice movement. As the Smithsonian Magazine explained:

Between 1917 and 1932, nearly 5,000 rural schoolhouses, modest one-, two-, and three-teacher buildings known as Rosenwald Schools, came to exclusively serve more than 700,000 Black children over four decades. It was through the shared ideals and a partnership between Booker T. Washington, an educator, intellectual and prominent African American thought leader, and Julius Rosenwald, a German-Jewish immigrant who accumulated his wealth as head of the behemoth retailer, Sears, Roebuck & Company, that Rosenwald Schools would come to comprise more than one in five Black schools operating throughout the South by 1928.

The Rosenwald schools played a vital role in advancing Black education in the American South and resembled the later charter school movement in important ways, with philanthropy providing the building infrastructure and other startup needs, with the states paying for the ongoing operating funding. Like charter schools today, the states in question did not fund Rosenwald schools on an equitable per pupil basis. Nevertheless, they made a lasting contribution.

The Rosenwald school movement began a long decline with the passing of Julius Rosenwald in 1932. Rosenwald had hoped that states would continue to build these schools, but this hope was dashed. Concentrated in rural areas and operating in the Jim Crow South, these schools were incredibly disadvantaged in advocating their cases in state legislatures. While a few of the Rosenwald buildings continue to exist, they stopped functioning as schools many decades ago.

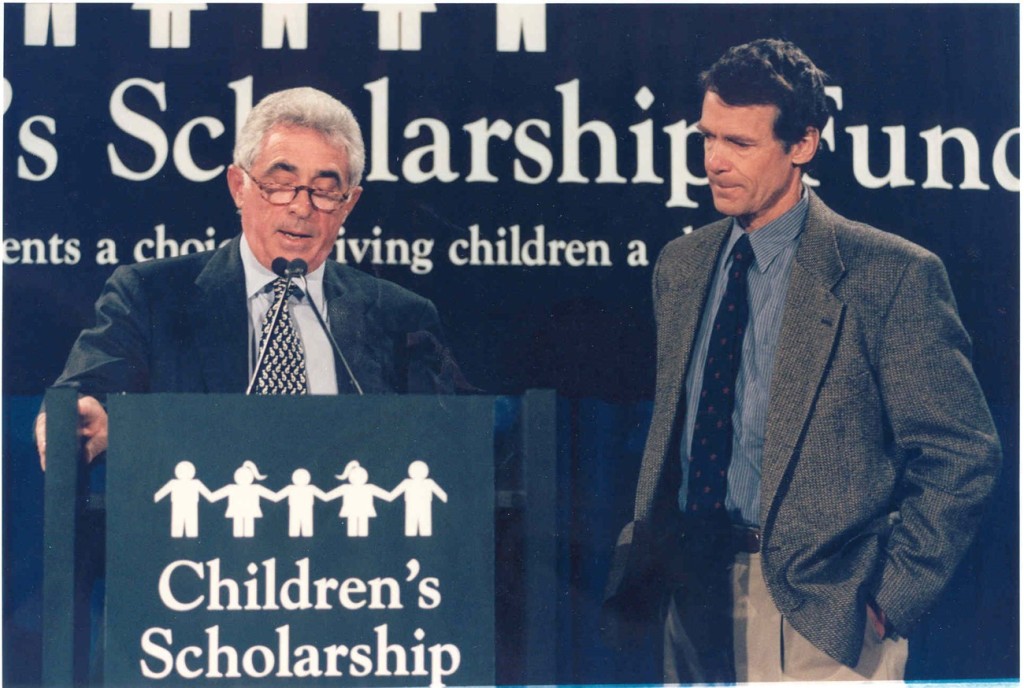

A more enduring legacy awaits latter day education philanthropists such as John Walton and Ted Forstmann. Together Walton and Forstmann founded the Children’s Scholarship Fund, which has granted almost a billion dollars in scholarships. Unlike Rosenwald, Walton and Forstmann have seen a now majority of states take up the role of financing alternative schools through mechanisms such as vouchers, tax credits and education savings account programs. A whole new generation of small community schools has emerged in the process, such as those featured here on Reimagined:

Unlike the Rosenwald schools, or sadly even charter schools in most states, the next generation of community schooling has already included all types of communities, leading to a broader base of support. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Dealers figured out that the best way to secure social insurance programs was to include everyone somewhere back around the time of Rosenwald’s death. Accordingly, Social Security is alive and well while Rosenwald schools lived their time but then faded due to a lack of political support.

Many decades passed before the choice movement embraced the New Deal insight, but much better late than never. Now America families and educators have a movement built to last.

Editor's note: This post was originally published in the The Hechinger Report.

What is the best way to teach? Some educators like to deliver clear explanations to students. Others favor discussions or group work. Project-based learning is trendy. But a June 2023 study from England could override all these debates: the most effective use of class time may depend on the subject.

The researchers found that students who spent more time in class solving practice problems on their own and taking quizzes and tests tended to have higher scores in math. It was just the opposite in English class. Teachers who allocated more class time to discussions and group work ended up with higher scorers in that subject.

“There does seem to be a difference between language and math in the best use of time in class,” said Eric Taylor, an economist who studies education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and one of the study’s authors. “I think that is contradictory to what some people would expect and believe.”

Indeed, the way that the 250 secondary school teachers in this study taught didn’t differ that much between math and English. For example, math teachers were almost as likely to devote most or all of the hour of class time to group discussions as English teachers were: 35 percent compared to 41 percent. Lectures were one of the least common uses of time in both subjects.

The study, “Teacher’s use of class time and student achievement,” published in the Economics of Education Review, gives us a rare glimpse inside classrooms thanks to a sister experiment in teacher ratings that provided the data for this study. Teachers observed their colleagues and filled out surveys on how frequently teachers were doing various instructional activities.

To continue reading, go here,

Editor's note: This year, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed legislation establishing a four-year pilot program to study whether year-round school helps eliminate learning loss. The following national commentary about time spent in American schools was written by Frederick Hess, director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute. It originally appeared in Forbes.

Should we be worried that our kids are getting less instruction than their global peers? Advocates and public officials sure are. They’ve long argued that American students need to spend more time in school. Such pleas have been redoubled in the aftermath of the pandemic, with New Mexico just this spring adding weeks to its mandated school year.

Former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan once told a congressional hearing, “Our students today are competing against children in India and China. Those students are going to school 25 to 30 percent longer than we are. Our students, I think, are at a competitive disadvantage.”

But are the concerns well-founded?

Not necessarily. Getting kids back in school after pandemic closures and disruptions was necessary and vital. But more generally, as I explain in The Great School Rethink, it turns out that American kids spend a lot of time in school compared to their peers around the world. And many parents came away from pandemic-era remote learning with a sense that students do less each day than they’d previously thought.

It’s true that the U.S. school year is on the shorter side when compared to other advanced economies. Most U.S. students attend school 180 days each year. In Finland, the maximum year is 190 days (though many schools employ a shorter calendar). The school year is 190 days in Hong Kong, Germany, and New Zealand; 200 in the Netherlands; 210 in Japan; and 220 in South Korea.

When tallying instructional time, though, it’s not just days in school; it’s also the time in each school day. The typical school day for American students is over six and a half hours. For Finnish students, it’s about five hours. In Germany, it’s five and a half. In Japan, it’s six.

Among Ilen Perez-Valdez’ many accolades: National Honor Society member, Immaculate-LaSalle’s Spanish Honors Society president, Science Honors Society vice president, and English Honors Society treasurer.

MIAMI – Nery Perez-Valdes wanted to become a doctor, but life got in the way.

She fled Cuba for Miami with her mom when she was 11 and found herself working at 14 to help pay the bills. Nery would become a single mom and for a long stretch worked two jobs to keep the lights on and food on the table.

Nery always wanted a private school education for her daughter, Ilen, and a Florida Tax Credit Scholarship made possible by corporate donations to Step Up For Students allowed that to happen.

“I was a single mom since I was three months pregnant, and when I’m saying, ‘single mom,’ I’m telling you ‘single mom.’ No child support. No help. No nothing. Period. The end,” Nery said. “Thanks to Step Up For Students, Ilen was able to get the education I wanted for her.”

Ilen has made the most of that opportunity – and then some.

She graduated this spring near the top of her class at Immaculate-LaSalle High School, a prestigious Catholic school in Miami. She has a scholarship to the University of Miami and plans to major in neuroscience and double minor in business administration management and Spanish. Her goal is to attend medical school and become a pediatric oncologist.

“My mother never received a college education. She was barely able to graduate high school. All she has done since she got (to the United States) is work, work, work,” Ilen said. “She came here looking for the American dream. I feel like if I succeed, she can live out her American dream through me.”

Ilen has received a Florida Tax Credit Scholarship since kindergarten. She said she’s grateful for the opportunity to receive a quality education – first at Saint Agatha Catholic School, and then at Immaculata-LaSalle.

“It was really difficult to make ends meet when I was younger, so I wouldn’t have been able to attend a private school where I received such an excellent education,” she said.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This article about Black Minds Matter founder Denisha Allen appeared recently on theharlemtimes.com. To read a report about Black educator-entrepreneurs authored by Allen and Step Up For Students’ Ron Matus, click here.

Editor’s note: This article about Black Minds Matter founder Denisha Allen appeared recently on theharlemtimes.com. To read a report about Black educator-entrepreneurs authored by Allen and Step Up For Students’ Ron Matus, click here.

Denisha Allen’s journey from a troubled student to a master’s degree graduate and leader in education reform is a model of the American Dream. Born in a poor neighborhood in Jacksonville, Florida, Denisha’s early experience with public schools was about as bad as it gets.

Her life at home was a struggle, and going to school was like going off to battle. Her mom and uncles had already dropped out, and her teachers had already given up on her because she shared their last name. She was terrified of being called on in class because she was reading below her grade level and regularly had to avoid getting into physical and emotional fights with her classmates.

Then things began to change. She moved in with her godmother who applied for a state scholarship program to a small private school. It was a revelation. Her new school was immaculate, and every day, teachers greeted the kids with smiles and sunny personalities.

She was able to let her guard down and for the first time felt compelled to compete in academics. She received one-on-one tutelage, and her reading and math ability jumped above her grade level. Denisha’s biggest concern became not achieving honor roll. In junior and senior year, she achieved straight A’s and went on to graduate with a master’s in social work from the University of South Florida.

She worked in the U.S Department of Education for two years and then the American Federation for Children where she started Black Minds Matter.

Denisha went on to share her success story at her old school and church. While her family wasn’t thrilled about the idea of sharing her humble beginnings, the experience was a form of therapy. She felt like a celebrity when she was invited by Governor Charlie Crist of Florida to promote his program for education reform and an expansion bill to target corporate dollars at primary school scholarships.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: reimaginED executive editor Matt Ladner submitted this post to us on behalf of author, Ed Jones, who leads High School Remixed and the education transformation lab Skunkworks\edu. Jones also is creator of the Science of Reading Mobile app.

Editor’s note: reimaginED executive editor Matt Ladner submitted this post to us on behalf of author, Ed Jones, who leads High School Remixed and the education transformation lab Skunkworks\edu. Jones also is creator of the Science of Reading Mobile app.

At long last, we have a name for the process that will transform high schools. The process itself has been described at length. Small, important, experiments have been launched, though not yet integrated and scaled. And now, finally, a name.

High-school-first IRC’s are, as the name suggests, industry credentials created specifically for teens in high school. Focusing on domain-specific knowledge for individual sectors of work and society, they will work better, and draw broader acceptance, than most IRC’s currently available to teens.

Importantly: The process for designing, testing, fielding, and building buy-in for high-school-first credentials will be very different from existing IRC’s or school curricula.

Those processes are relics of an earlier era and serve the needs of the providers as much as of the learners. Modern tools allow us to move beyond those limitations. Across the education and workforce policy world, laments of all kinds constantly summon a reimagining of high school’s form and function. As a solution to that high school redesign challenge, this approach:

Drops seamlessly into traditional schools.

No “redesign” of the school day. It just works.

Uses new education freedom laws.

As more states enact these, the process will become even easier. However, no specific laws are required for HSFIRCs to be used in schools. These laws include “learn-everywhere” policies that allow state-designated non-school orgs to offer credit-bearing courses; and policies like Ohio’s Credit Flexibility law that empowers any student to learn and earn credit on nearly any topic from nearly any source. More, as states continue to roll out education savings accounts, the budgets to support HAFIRC teaching, assessment, and even curricular development will grow. In more traditional settings, a staff teacher can simply make them part of a course.

Builds on the system of Industry Recognized Credentials.

As IRC’s have been fielded across the various states, we’re beginning to learn how they are used, and to what effects. Early (limited) data is indicating that they’re not yet being broadly used, and not entirely helping the students they were most designed to aid. Still, the IRC system itself nicely lays the groundwork for a next-generation approach.

Each credential built from the ground up—with high school teens in mind.

Current IRC’s are built to serve various different masters. Many are built simply to provide a training firm revenue, with minimal post-deployment reinvestment. Some have deep specification and review from the industry or labor specialists themselves. Others, e.g. Microsoft Office or Adobe Illustrator certificates, are built around specific products. Still others just give graduation credit for passing a state exam. (In Ohio, a commercial drivers license earns one Carnegie Unit.) HSFIRCs will be more broadly useful to young adults.

Built for the teens in the middle.

For years, ‘college and career’ focus has tended toward either the top third, or else specific everyday trades. HSFIRCs will serve those heading for jobs between automotive tech and high school biology teacher. Plus, allow for learning for good citizenship—a need greatly highlighted by the most recent NAEP release.

Process allows rapid improvements.

Workforce experts frequently lament the lag time between industry developments and school coursework; as they did at an Ohio tech summit last month. While such lags are sometimes inevitable, there is much that a better, more modern process of course creation and maintenance can do to shorten them or mitigate their effects.

Broad, ongoing involvement of multiple parties.

By using open source tools and processes, new communities will grow around these credentials. Such procedures will allow teachers, industry professionals, curriculum designers, local organizations, and even parents and students themselves to participate continuously in the ongoing evolution of each training unit, and to regularly improve the quality of the intermediate and final assessments. Generally little understood by education experts, open source tools have evolved greatly in the past decade. (They certainly go far beyond the—still critical—Creative Commons licenses.) Iterated since the 1991/1993 releases of Apache web server and the Linux operating system, they facilitate transparent reuse, sharing, versioning, rights management, issue tracking, package management, security, etc.

Modular design allows improving individual pieces.

An evolving feature of existing IRCs is the point system, where 12 points is the equivalent of one Carnegie Unit. This means that a one-point credential approximately represents ten hours of work. By regularizing the use of one-point/ten-hour units, we can begin to build a system of interchangeable parts. The term “stackable credentials” refers to one aspect of this: aggregating smaller credentials into larger ones. Yet, modularity can also be used to improve quality and reduce costs, as developers freely use and improve openly licensed lessons and lesson components (video scenes, voice scripts, graphics, code).

Allows much higher quality to rise to precedence.

The bar to acceptance of a high-school-first credential will not be low. Unlike other credentials, its acceptance will depend far more upon obvious need + quality than on the approval of a particular small group of people.

Collaboration Over Confrontation.

Source communities are simply different from the discussions that normally take place around K12 education. They put the energy of disagreement to better, more productive use. To borrow a phase from the K12 research profession, “it’s better to be very specifically wrong than vaguely right”. In such communities, your vague statements will be disregarded while your specific addition will be lauded. The culture of open source is to contribute to where you can, and be respectfully silent where you can’t.

In disruptive innovation theory, an innovative business model best evolves when it first targets non-consumers (new customers who previously did not buy products or services in a given market) or low-end consumers (the least profitable customers). It uses enabling technology to make the product more accessible to a wider population.

Using those, it builds up a new coherent value network: a network in which suppliers, partners, distributors, and customers are each better off when the disruptive technology prospers.

A huge amount of work remains to put a prototype high-school-first credential into common use. Making this open source process doable by stakeholders will take time. Yet, the second credential will be far easier than the first, and the third-to-thirtieth that much easier again—as they successively dovetail into a well-developed formula and process.

This month, Rick Hess wrote of “A Broader, More Practical Focus” through new forms of educational choice. Making this easy for parents, students, and teachers is key.

“Many teenagers are sleepwalking through high school,” said Fordham in their high school wonkathon RFP, “and our high schools are sleepwalking through the twenty-first century.

“There’s a lot of talk about reimagining high schools, but very little transformative action.”

Now that we finally have a name, let the transformative action begin.

Crown Point Christian School in St. John, Indiana, is one of about 650 private schools in the state. Committed to academic excellence, Crown Point trains children to understand the world around them and to recognize that "every part belongs to God."

Editor’s note: This article appeared Tuesday on stateaffairs.com.

Eligibility for Indiana’s school choice voucher program is poised to dramatically increase next school year, enabling roughly 97% of students to use state money to attend private schools, according to school choice advocates.

State lawmakers have slowly expanded the program since they implemented it more than a decade ago. The state released its annual school choice report last month which provides insight into where the program stands ahead of arguably its largest expansion to date.

Already, between the 2021-2022 school year and the 2022-2023 school year, the cost to state taxpayers for the program grew by 30%, the report shows. That’s before the latest eligibility expansion goes into effect.

The 2022-2023 school year was the state’s largest increase in the number of students claiming vouchers since the 2014-2015 school year.

This past school year, a family of four had to earn around $154,000 per year or less for a student to qualify to receive state money to attend a private school. In the two-year state budget passed in April, lawmakers expanded the eligibility to allow those making 400% of the income required to qualify for free or reduced-price lunches to participate in the school choice program.

Likewise, state lawmakers simplified eligibility by removing other requirements.

That means a family of four earning up to $220,000 per year will qualify this upcoming year, including students who have already been attending private school on their family’s own dime. Robert Enlow, the president and CEO of EdChoice, called Indiana’s program “effectively universal.”

“It’s unfair to pay twice, once in taxes and once in tuition,” Enlow said. “[The new policy has] basically said to almost every parent in the state of Indiana that we trust your choices.”

Costs for the program are expected to balloon by more than 70% in the first year. By fiscal year 2025, the state will spend an estimated $600 million on vouchers per year.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Robert Enlow, president and CEO of EdChoice, appears in the Spring 2023 issue of Education Next.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Robert Enlow, president and CEO of EdChoice, appears in the Spring 2023 issue of Education Next.

One in seven of America’s K-12 students has recently gained education freedom. Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, South Carolina, Utah, and West Virginia have funded education savings accounts for all or nearly all their families. Those families, in turn, can use their ESAs for a variety of education expenses, including tuition, curriculum, tutoring, and therapies.

ESAs empower teachers and families to customize the education for each unique child. As an added benefit, ESAs foster positive competition for public schools, bringing in a rising tide that lifts all educational boats for children.

These ESA laws mark the start of a major shift in how K-12 education in America is funded and delivered. Now, the real work begins. Passing strong ESA laws is hard, but implementing these programs with excellence is harder.

For the education freedom movement, nothing is more important right now than implementing with excellence. Education freedom will only thrive when the public trusts parents, not bureaucrats, to be in charge of their children’s education. That trust will only build as student outcomes improve, as parents and teachers are empowered, and as programs are executed with excellence.

Quite simply, if we do not follow good policy with excellent, parent-centered implementation, we risk ruining it for everyone, starting with our children.

The logistics of ESA programs can be daunting, as states put purchasing power directly into the hands of millions of families, create a “marketplace” where families can select and pay from a wide selection of approved schools, tutors, and other education-related vendors, and then hold everyone accountable for complying with relevant laws and rules.

Fortunately, past experiences from across the country offer lessons on how to make a daunting task easier as we move from policy to practice.

The policy shift is partly a mind shift. For a century, policymakers have largely chosen to put the needs of the K-12 system above those of individual students in a drive for efficiency, consistency, and uniformity. The result is a factory model where children and teachers are too often treated as widgets, and where nearly one-third of children are failing to learn how to read a basic, grade-level text.

The system’s current multi-layered bureaucracy will have trouble adjusting to a system designed to meet the unique needs of each child. Most of the current system’s government workers will be reluctant, at best, to publicize the availability of education freedom. Their jobs depend on having captive customers, and it is difficult for them to embrace a world where students are not forced to attend a zoned school and get assigned to classrooms.

To continue reading, click here.