Tennessee’s education savings account program, championed by Gov. Bill Lee when he was a first-year Republican, narrowly passed in 2019 with some opposition from Republicans and almost all Democrats.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Monday on nashvillescene.com.

Tennessee’s private school voucher program cleared another legal challenge on Wednesday. The Davidson County Chancery Court ruled in favor of the education savings account program and dismissed legal claims related to it.

The ESA program, which was championed by Gov. Bill Lee and narrowly passed in 2019, allows certain students in Nashville and Memphis to use public dollars to attend private schools.

The program was initially challenged in 2020, before it had been instituted. Since then, ESAs saw several rounds of litigation before the program was green-lit to move forward in July. Following that ruling, the state rapidly began implementing the program for the 2022-23 school year.

Wednesday’s decision, which followed a September hearing, considered arguments from Davidson and Shelby counties and parents against the state and other ESA supporters — multiple lawsuits were consolidated in this case. The plaintiffs argued that the program violates the equal protection and education clauses of the state constitution, and that each city would be harmed from the loss of education-related funding that would occur when students drop out of public schools and go to private schools.

The defendants argued that the claims are not yet ripe, since a state “school improvement fund” would pay back the lost funding to the affected counties for three years.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: The Step Up For Students team of Ron Matus, director, policy and public affairs, and Dava Hankerson, director, enterprise data and research, provides an overview in this post of their recent brief demonstrating that education choice is growing in rural Florida. You can view the full brief here.

The Democratic candidate for governor of Oklahoma this year made it a hallmark of her campaign to claim private school choice would devastate rural public schools and the communities they serve. She called choice a “rural school killer.”

The candidate lost. But the myth lives on, not only in Oklahoma but in other states with vast stretches of rural heartland and little to no school choice.

To combat it, we turn to a state that actually has a lot of choice in rural areas: Florida.

Our new brief, “Rerouting the Myths of Rural Education Choice,” highlights five key facts about choice in rural Florida. To put faces on the facts, we also produced a short video spotlighting a rural school founded by a former public school district Teacher of the Year.

Florida is well positioned for myth busting here. It’s been a national leader in expanding education choice for two decades, and its rural communities have benefited.

Florida has highly regarded charter schools from the Forgotten Coast in the Panhandle to the edge of the Everglades. It has high-quality private schools from the Apalachicola National Forest to the heart of Florida cattle country. And in scores of small towns like Chipley and Williston and LaBelle, it has resourceful parents using state-funded education savings accounts (ESAs) to customize learning for their children.

At the same time – and this is critical – the expansion of private school choice and ESAs has not put much of a dent in rural public school districts.

More than 70% of Florida families are eligible for income-based choice scholarships. Yet over the past 10 years, the share of rural students enrolled in private schools rose a mere 2.4 percentage points.

So, on the one hand, education choice is helping thousands of rural families access life-changing options for their kids. On the other, the overwhelming majority of rural families continue to choose district schools.

Policymakers should proceed accordingly.

Ivonne Torres, a senior and captain of the robotics team at Sunset High School in Dallas, shows special education students Tomas Sosa (left) and Josh Preciado how to put a battery into a controller during an after-school session. PHOTO: Dallas Morning News

Editor’s note: This article appeared last week on dallasnews.com.

Texas lawmakers want a better way to educate students with disabilities, but will they turn to voucher-like programs to do so? A committee’s recent debate on expanding microgrants and other school-choice options could foreshadow the anticipated fight over school vouchers.

The Texas Commission on Special Education Funding recently discussed draft recommendations that include expanding a program that awards families of students with special needs one-time grants to use toward education services, such as tutoring or therapy. Supporters called the grants “one step away” from voucher-like efforts.

This month, the commission heard testimony on whether Texas should create education savings accounts for students with disabilities. Such accounts give parents public funds directly to pay for private-school tuition or for other education expenses.

More than a dozen speakers, including researchers, lobbyists, advocates and parents, spoke during the hearing that lasted more than five hours. Many touted the success of similar programs in other states, while others passionately warned the commission about the negative impacts voucher-like initiatives can have when they divert funding from public schools.

Many private schools could make room for students with education savings accounts, said Laura Colangelo, executive director of the Texas Private Schools Associations.

“There are many parents desperate for this option,” Colangelo told lawmakers.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This report from Jonathan Butcher, Will Skillman Fellow in Education, Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, and Jason Bedrick, Research Fellow, Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, concludes that education savings accounts empower parents with the ability to meet every child’s unique education needs and should be available to all school-aged children. It includes a review of changes to education savings account plans around the country, specifically in Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

Editor’s note: This report from Jonathan Butcher, Will Skillman Fellow in Education, Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, and Jason Bedrick, Research Fellow, Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, concludes that education savings accounts empower parents with the ability to meet every child’s unique education needs and should be available to all school-aged children. It includes a review of changes to education savings account plans around the country, specifically in Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

In July 2022, Arizona lawmakers converted the nation’s oldest K–12 education savings account (ESA) policy into the country’s most inclusive learning option: Every child in Arizona can now apply for a private account that empowers families to customize a student’s learning experience according to his or her unique needs.

News Release, “Governor Ducey Signs Most Expansive School Choice Legislation in Recent Memory,” Office of Arizona Governor Doug Ducey, July 7, 2022, https://azgovernor.gov/governor/news/2022/07/governor-ducey-signs-most-expansive-school-choice-legislation-recent-memory (accessed October 12, 2022).

With an ESA, the state deposits a portion of a child’s education spending from the state K–12 formula—the formula used to determine per-student spending in traditional schools—into a private account that parents use to buy education products and services for their children. The accounts are worth approximately $7,000 for mainstream children, with larger amounts awarded to children with special needs.

Families can use an ESA to hire a personal tutor for their child, find an education therapist, pay private school tuition, buy curricula and textbooks, save money from year to year for future expenses, and more. The accounts allow families to choose more than one education product or service; moreover, they provide the versatility parents needed to continue their children’s education during the pandemic when schools were closed to in-person learning.

Jonathan Butcher, “COVID-19 Has Accentuated Value of Education Savings Accounts,” reimaginED, May 12, 2020, https://nextstepsblog.org/2020/05/covid-19-has-accentuated-value-of-education-savings-accounts/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

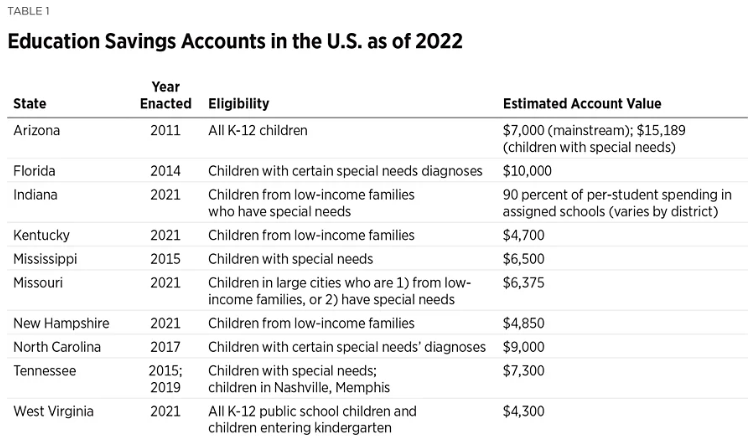

Arizona lawmakers adopted the nation’s first ESAs for children with special needs in 2011, and nine other states (Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia) subsequently created similar ESA opportunities for eligible students. Each state offers accounts to children who meet different criteria.

After the pandemic, as researchers report steep learning losses across grade levels and subjects, the call for quality learning options is especially urgent. Arizona’s new law is remarkable because all K–12 children can participate.

In Florida and Tennessee, for example, children with certain special needs are eligible, while Mississippi and North Carolina’s accounts operate under strict caps on the number of participating students due to either provisions in state law or annual appropriations. In West Virginia, all children attending public schools or entering kindergarten are eligible, making it the second-most inclusive ESA policy behind Arizona’s.

Research conducted by The Heritage Foundation in 2017 helps to explain the eligibility criteria and other account details for the savings accounts in Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Tennessee, but much has changed in the past five years.

Jonathan Butcher, “A Primer on Education Savings Accounts,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3245, September 15, 2017, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2017-09/BG3245.pdf.

The 2017 report also distinguished between the accounts, which allow families to purchase more than one education product or service at the same time, and school vouchers, which parents can only use to pay private school tuition for their children. The accounts also differ from tax-credit scholarship policies, which provide tax credits to individuals or corporations that make charitable donations to nonprofit organizations that in turn award private school scholarships to eligible students.

Jason Bedrick, “Earning Full Credit: A Toolkit for Designing Tax-Credit Scholarship Policies (2022 Edition),” Pioneer Institute, March 30, 2022, https://pioneerinstitute.org/pioneer-research/earning-full-credit-a-toolkit-for-designing-tax-credit-scholarship-policies-2022-edition/ (accessed October 31, 2022).

In this Backgrounder, we will review the changes to education savings account plans around the country, offer an analysis of the new states with ESA laws, and provide policy recommendations for the future of ESAs.

What’s changed?

Nearly all education savings account plans created since Arizona introduced the concept in 2011 have changed eligibility, funding mechanisms, or other significant provisions:

Arizona. Arizona’s accounts were initially only available to children with special needs but expanded to include children assigned to failing schools and children adopted from the state foster care system in 2012.

Butcher, “A Primer on Education Savings Accounts.”

Lawmakers later expanded student eligibility to include children from active-duty military families and children living on tribal lands, among others. In 2022, Arizona opened eligibility to every K–12 student in the state, some 1.1 million school children.

News release, “Governor Ducey Signs Most Expansive School Choice Legislation in Recent Memory.”

When Governor Doug Ducey (R) signed the expansion, 11,775 Arizona students were using the accounts, and after the application period opened in September 2022, the state department of education received about 22,500 new applications from interested families within two months.

Jason Bedrick and Jonathan Butcher, “Arizona Shows the Nation What Education Freedom Looks Like,” Newsweek, September 14, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/arizona-shows-nation-what-education-freedom-looks-like-opinion-1742145 (accessed October 12, 2022); EdChoice, “Arizona: Empowerment Scholarship Accounts,” https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/arizona-empowerment-scholarship-accounts/ (accessed October 31, 2022); and Christine Accurso, “Arizona’s New ESA School Choice Law Is a Win for Everyone,” The Washington Examiner, September 9, 2022, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/restoring-america/community-family/arizonas-new-esa-school-choice-law-is-a-win-for-everyone (accessed October 12, 2022); Eryka Forquer, “Applications for school vouchers at nearly 22,500 so far, Education Department says,” Arizona Republic, October 7, 2022, https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona-education/2022/10/07/arizona-school-vouchers-nearly-22-500-applications-pour-so-far/8208504001/ (accessed November 3, 2022).

Florida. In 2014, Florida lawmakers enacted the nation’s second education savings accounts, called Gardiner Scholarships. In 2021, state officials adopted a proposal to combine the program with the state’s K–12 private school scholarship program, called Family Empowerment Scholarships, creating the Family Empowerment Scholarships for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA).

Step Up for Students, “Basic Program Facts about the Family Empowerment Scholarship (formerly the Gardiner Scholarship),” https://www.stepupforstudents.org/research-and-reports/gardiner-scholarship/basic-program-facts-gardiner/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

In the 2021–2022 school year, 21,155 children were using accounts.

Step Up for Students, “Family Empowerment Scholarship for Children with Unique Abilities,” August 2022, https://www.stepupforstudents.org/wp-content/uploads/2022.8.10-FES-UA-ESA.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022).

North Carolina. North Carolina lawmakers enacted Personal Education Savings Accounts in 2017, but in the 2022–2023 school year, these accounts will merge with the state’s K–12 private school scholarships for children with special needs (Disability Grants).

North Carolina State Education Assistance Authority, “Education Student Accounts (ESA+) Program,” https://www.ncseaa.edu/k12/esa/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Account holders will still be able to purchase more than one education product or service, a feature of the accounts in every state with such a program. Some students with special needs may be eligible for accounts worth up to $17,000 (an increase from the original account award of $9,000).

Account holders can also participate in the Disability Grant program and the state’s Opportunity Scholarships, which are K–12 private school scholarships for children from low-income families. As of March 2022, 658 students were using an account.

North Carolina Education Assistance Authority, “Education Savings Account Summary of Data,” March 16, 2022, https://www.ncseaa.edu/education-savings-account-summary-of-data/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Tennessee. Tennessee lawmakers allowed children with certain special needs to access accounts in 2015. (The program officially launched in 2017.)

Tennessee General Assembly, 2015 Session, S.B. 27, https://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/BillInfo/Default.aspx?BillNumber=SB0027 (accessed October 31, 2022).

In the 2020–2021 school year, 307 students were using the accounts.

EdChoice, “Tennessee: Individualized Education Account Program,” https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/tennessee-individualized-education-account-program/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

In 2019, lawmakers adopted another ESA proposal, with these accounts available to children in Nashville and Memphis (Shelby County). School district officials sued to force children to remain in assigned schools, but in June 2022, the state supreme court ruled that the program could begin operation in the coming school year. In August, the Chancery Court for Davidson County rejected more motions that would have stalled the program.

Conor Beck, “Court Victory for Parents Defending Tennessee’s Educational Savings Account Program,” Institute for Justice, August 5, 2022, https://ij.org/press-release/court-victory-for-parents-defending-tennessees-educational-savings-account-program/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

New state laws

In 2021, lawmakers in five states adopted new education savings account plans, including two that combined tax-credit scholarships with education savings accounts:

West Virginia. West Virginia lawmakers adopted a proposal that made nearly every child in the state eligible to apply for an account, making it the most expansive account any state officials had approved at that time, and the second-most expansive after Arizona’s universal expansion in 2022.

West Virginia Legislature, 2021 Regular Session, HB 2013, https://www.wvlegislature.gov/Bill_Status/bills_history.cfm?INPUT=2013&year=2021&sessiontype=RS (accessed October 31, 2022).

All students attending a public school in West Virginia for at least 45 days or who are entering kindergarten are eligible to apply for the accounts, aptly named Hope Scholarships.

Lawmakers require students to attend a public school for 45 days because by that time in the school year the student is included in the traditional school funding formula for that year. Then, if the student uses an education savings account, the taxpayer money from the public school formula “follows” the child to an education savings account and no new taxpayer money is needed. If a child was in a private school or homeschooled, new taxpayer money would need to be added to the state treasury to fund that child’s account. If students are required to attend a public school before using an account, the education savings account program will not generate a fiscal note stating that new taxpayer money is required for students to use the accounts.

Similar to the accounts in Arizona, state officials deposit a child’s portion of the state school spending formula into a private account that parents can use to buy multiple products and services.

Each account will be worth approximately $4,300, according to the Cardinal Institute, a research institute in West Virginia.

Cardinal Institute, “Questions from Parents,” https://www.cardinalinstitute.com/questions-from-parents/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Parents can use the accounts for personal tutors and education therapies, along with private school tuition and private online learning programs.

Implementation of the ESA policy was delayed because education industry special interest groups supported a lawsuit to force account holders back into assigned public schools. The state supreme court of appeals agreed to consider the case, and on October 6, 2022, the court upheld the program, removing an injunction that had prevented families from using the accounts.

Brad McElhinny, “Supreme Court Takes Over Hope Scholarship Appeal, Promises Hearing Soon, Says No to Stay,” MetroNews, August 18, 2022, https://wvmetronews.com/2022/08/18/supreme-court-takes-over-hope-scholarship-appeal-promises-hearing-soon-says-no-to-stay/#:~:text=Hearing%20a%20challenge%20to%20the,from%20the%20public%20education%20system (accessed October 12, 2022), and Amanda Kieffer, “Press Release: Cardinal Institute Celebrates Historic Win for West Virginia Families,” Cardinal Institute, October 6, 2022, https://www.cardinalinstitute.com/press-release/wvscoa-upholds-hope-scholarship/ (accessed October 31, 2022).

The program is now fully operational.

Conor Beck, “Victory for School Choice in West Virginia,” Institute for Justice, October 6, 2022, https://ij.org/press-release/victory-for-school-choice-in-west-virginia/ (accessed October 31, 2022).

Indiana. Indiana lawmakers adopted an account proposal that allows children with special needs from low- and middle-income families (i.e., household incomes of up to 300 percent of the income eligibility guidelines for the federal free- or reduced-priced lunch program).

Indiana General Assembly, 2021 Session, HB 1001, https://iga.in.gov/legislative/2021/bills/house/1001#document-dbc2cc8e (accessed October 31, 2022).

Students do not have to attend a public school before applying for an account.

State officials limited funding for the accounts so that only 2,000 students can participate in 2022.

EdChoice, “Indiana: Education Scholarship Account Program,” https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/education-scholarship-account-program/ (accessed October 31, 2022).

New Hampshire. In New Hampshire, officials adopted Education Freedom Accounts in 2021. The accounts are available to students from households with incomes at or below 300 percent of the federal poverty line ($83,250 for a family of four in 2022–2023).

New Hampshire General Court, 2021 Session, HB 2, https://gencourt.state.nh.us/bill_status/legacy/bs2016/bill_status.aspx?lsr=1082&sy=2021&sortoption=&txtsessionyear=2021&txtbillnumber=HB2 (accessed October 31, 2022).

The accounts are administered by a K–12 private school scholarship organization, Children’s Scholarship Fund NH.

Education Freedom Coalition, Education Freedom NH, https://educationfreedomnh.org/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

In its first year of operation (the 2021–2022 school year), nearly 2,000 children used accounts. That amounts to more than 1 percent of K–12 students in the Granite State—a record enrollment, per capita, for the first year of operation of any education choice policy. Each account was worth approximately $3,400. As of September 2022, more than 3,025 students are receiving ESAs worth an average of $4,857.

Children’s Scholarship Fund New Hampshire, “Frequently Asked Questions,” https://1b2.ee8.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/NH-FAQ-2.28.22.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022); Ethan Dewitt, “Education Freedom Accounts Double after One Year; Most Recipients outside Public School,” New Hampshire Bulletin, September 15, 2022, https://newhampshirebulletin.com/briefs/education-freedom-accounts-double-after-one-year-most-recipients-outside-public-school/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Kentucky. Bluegrass State lawmakers created accounts funded by charitable donations to nonprofit, scholarship-granting organizations.

In Kentucky the new ESA Policy allows students to choose from a variety of education products and services in addition to private school tuition.

Kentucky Legislature, 2021 Session, HB 563, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/21rs/hb563.html (accessed October 31, 2022).

Eligible students include children in households with incomes of up to 175 percent of the income limit for the federal free- or reduced-priced lunch program.

The program has restrictive features not found in other states’ account offerings, though. One such feature prevents participants from receiving account funding if his or her household income increases to a figure greater than 250 percent of the income limit for free- or reduced-priced lunch.

EdChoice, “Kentucky: Education Opportunity Account Program,” https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/education-opportunity-account-program/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Another provision states that only students living in large counties (with populations greater than 90,000) can use their accounts for private school tuition.

Lawmakers have not implemented Kentucky’s program yet due to a lawsuit challenging the accounts.

Kentucky Department of Revenue, “Education Opportunity Account Program,” October 12, 2021, https://revenue.ky.gov/News/Pages/Education-Opportunity-Account-Program.aspx (accessed October 31, 2022).

Missouri. Lawmakers in Missouri, as in Kentucky, adopted an education savings account program that is funded via charitable contributions to scholarship-granting organizations.

101st Missouri General Assembly, 1st Regular Session, HB 349, https://house.mo.gov/Bill.aspx?bill=HB349&year=2021&code=R (accessed October 31, 2022).

Individuals will receive tax credits of up to 100 percent of their donations but the amount of credits claimed by any donor cannot exceed half of their annual state tax liability. Only 10 scholarship organizations are allowed to award accounts.

Cameron Gerber, “Parson Signs New ESA Program into Law,” The Missouri Times, September 7, 2022, https://themissouritimes.com/parson-signs-new-esa-program-into-law/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Lawmakers limited the total amount of tax credits awarded to contributors to $25 million in the program’s first year.

Research

Since lawmakers’ adoption of the first account program in Arizona in 2011, research has demonstrated that account holders use their ESAs for more than private school tuition. The versatility of the accounts, which distinguishes them from K–12 private school vouchers, has allowed families to meet their children’s unique needs.

This distinction is important because in states with constitutional provisions that restrict the use of public spending on private learning options (known as “Blaine” amendments), parents’ ability to choose more than one learning option has allowed the accounts to survive judicial scrutiny in state courts that are hostile to traditional vouchers.

Parents’ ability to use ESAs for several education products and services at the same time is crucial for providing quality learning experiences outside the classroom.

In 2013 and 2016, researchers found that approximately one-third of Arizona account holders used their child’s ESA for more than one education product or service.

Lindsey M. Burke, “The Education Debit Card: What Arizona Parents Purchase with Education Savings Accounts,” EdChoice, August 2013, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/2013-8-Education-Debit-Card-WEB-NEW.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022), and Jonathan Butcher and Lindsey M. Burke, “The Education Debit Card II: What Arizona Parents Purchase with Education Savings Accounts,” EdChoice, February 2016, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2016-2-The-Education-Debit-Card-II-WEB-1.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022).

Again, parents’ access to textbooks, personal tutors, education therapists, online classes, and more is what makes the accounts unique among private learning options in states around the country.

In 2018, researchers found that more than one-third of account holders in Florida also used the ESAs for more than one purpose. This report also found that among these families purchasing more than one product or service, more than half (55 percent) paid for several products and services and did not purchase private school tuition—making them “customizers” of their children’s educations apart from private schools.

Lindsey Burke and Jason Bedrick, “Personalizing Education: How Florida Families Use Education Savings Accounts,” EdChoice, February 2018, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Personalizing-Education-By-Lindsey-Burke-and-Jason-Bedrick.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022).

More recent studies continue to substantiate these findings that separate the accounts from traditional K–12 scholarships. In 2021, a study of North Carolina account holders found, for the first time, that a majority of account holders used their child’s ESA for more than one product or service. Sixty-four percent of account holders used their child’s ESA to select more than one education item or service.

Jonathan Butcher, “A Culture of Personalized Learning,” John Locke Foundation, August 13, 2021, https://www.johnlocke.org/research/a-culture-of-personalized-learning/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

This figure is nearly double the share of families using the accounts in this way in the first two studies of ESA usage in Arizona.

This report also found that families using the accounts lived in ZIP codes where the average income was close to the statewide median. Fifty-three percent of account holders—more than half—live in areas in which the median income is within $10,000 of the statewide median. These findings mean that students from families of modest means are benefitting from the ESAs.

According to the report, families using private school scholarships at the same time as they participated in the state’s education savings account options in North Carolina also purchased more than one item or service. In North Carolina, families can access an education savings account and a K–12 private school scholarship option for children with special needs or from low-income families.

Even families that accessed an account and a scholarship used the new opportunities to pay for more than private school tuition, providing evidence that when the accounts are offered to families in addition to scholarships or vouchers, parents will still make education purchases according to a child’s needs.

A 2021 study analyzing Florida account holder spending found that parents continue to customize a child’s education when they remain with an ESA for longer periods. According to researchers Michelle L. Lofton and Marty Lueken, “The longer students remain in the program, the share of ESA funds devoted to private school tuition decreases while expenditure shares increase for curriculum, instruction, tutoring, and specialized services.”

Michelle L. Lofton and Martin F. Lueken, “Distribution of Education Savings Accounts Usage Among Families: Evidence from the Florida Gardner Program,” Brown University EdWorkingPaper No. 21-426, June 2021, https://www.edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai21-426.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022).

The percent of Florida ESA funds that parents used each school year increased from 60 percent in 2015 to 73 percent in 2016 to 88 percent in 2019. During this same period, however, the amount of account funds spent on education products outside of tuition (“instructional materials”) quadrupled. Here again, research demonstrates that parents will customize a child’s learning experience when they have the opportunity to purchase different services and items, and education savings accounts are meaningfully different from K–12 private school vouchers.

Policy recommendations

Eligibility. Lawmakers should give every child in their state the option to use an education savings account—and Members of Congress should do the same for K–12 students in Washington, DC, students living within federal jurisdictions, such as tribal lands and attending Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) schools, and children in active-duty military families.

Limiting account access creates a multi-tiered education system where certain families have more and better learning opportunities for their children than others. Furthermore, research on student achievement after the pandemic demonstrate that millions of children are not performing at age- or grade-appropriate levels and need help gaining essential life and academic skills.

Nation’s Report Card, “Reading and Mathematics Scores Decline During COVID-19 Pandemic,” 2022, https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/highlights/ltt/2022/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Lawmakers should act with a sense of urgency to help students catch up.

Funding. State officials should transfer a child’s portion of the state education spending formula into a private account that parents use to purchase education products and services. This method is preferable to plans that fund the accounts through annual appropriations, which are subject to legislative spending constraints each year and can require additional taxpayer spending.

Policymakers can follow the models in place in Arizona and now Florida, to name just two, that allow taxpayer spending to follow a child to their public or private learning choices.

Testing. State officials should allow participating private schools to choose the national norm referenced test—such as the Stanford series, the Iowa Test of Basic Skills, or the Classical Learning Test (CLT)—that best matches the institution’s curriculum and report aggregate results after a period of three years. The agency administering the accounts should contract with a survey company to measure parent satisfaction.

These two indicators—aggregate student results over time and parent satisfaction—should serve as the measures of success for account holders. Test results, though, should not determine student or school eligibility for participation in an account program.

Lawmakers should not require account holders to take state tests administered to public school students because such assessments impact instructional choices, thus affecting school officials’ curricular decisions and limiting parental options. Requiring account holders, homeschool students, or private school students to take state tests would produce uniformity, not an account option that allows for customization according to a child’s unique needs.

Conclusion

Every child should have the opportunity to succeed in school and in life. After the pandemic, as researchers report steep learning losses across grade levels and subjects, the call for quality learning options is especially urgent.

National Center for Education Statistics, “Reading and Mathematics Scores Decline During COVID-19 Pandemic,” NAEP Long-Term Trend Assessment Results: Reading and Mathematics, https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/highlights/ltt/2022/ (accessed October 31, 2022), and Clare Halloran, Rebecca Jack, James C. Okun and Emily Oster, “Pandemic Schooling Mode and Student Test Scores: Evidence from U.S. States,” National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2021, https://www.nber.org/papers/w29497 (accessed October 31, 2022).

Education savings accounts empower parents with the ability to meet every family and child’s unique education needs and should be available to all school-aged children. Students need options such as ESAs now more than ever.

Jim Hogg/Conroe Independent School District is a rural district located in the ranching community of Hebbronville, Texas, near the Rio Grande. According to the U.S. Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics, Texas has more than 2,000 campuses classified as being in rural areas.

Editor’s note: This commentary appeared last week on lubbockonline.com.

Is school choice bad for rural school districts? Joy Hofmeister certainly thinks so, going so far as to call vouchers and related programs “rural district killer[s].”

In case you aren’t familiar with Ms. Hofmeister, she’s the Oklahoma Superintendent of Public Education and was recently the Democratic candidate for governor. Election night didn’t go well for her: Incumbent Gov. Kevin Stitt, who supports school choice, cruised to a 55.5-41.8 victory. Ms. Hofmeister won only three counties, two of which contain Oklahoma City and Tulsa. Mr. Stitt won 63.2 percent of the vote outside these counties.

Evidently, rural parents are just fine with school choice. They don’t appreciate the efforts of Ms. Hofmeister and her ilk to restrict the educational options of Oklahoma’s children.

Texas politicians, take note: parents aren’t fooled by the false narrative on school choice anymore. School choice doesn’t hurt rural districts. If anything, it strengthens them by giving families additional options. Public education dollars should fund students, not systems. It’s time to make school choice a reality here in Texas.

School choice refers to a group of programs that give parents direct control over their children’s education funding. One example is vouchers: state-provided funds can be used for tuition at a school of the family’s choice.

A better example—one just implemented to great success in Arizona—is education savings accounts. Families can use state funds on a host of approved educational expenses, including homeschooling co-ops, “learning pods,” supplemental materials and activities, and mental health resources. It’s a transformative approach to education that puts students’ needs first.

To continue reading, click here.

West Virginia parent Katie Switzer, whose child has a speech disorder, praised the decision in a statement issued by the Institute for Justice, saying it will allow families to make the best educational decisions for their children.

The West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals, which last month upheld the constitutionality of the Hope Scholarship education choice program, issued on Thursday a 49-page majority decision that a traditional public education system and the statewide education savings account program can operate concurrently without violating the state constitution.

Justice Tim Armstead wrote:

“… we find that the West Virginia Constitution does not prohibit the Legislature from enacting the Hope Scholarship Act in addition to providing for a thorough and efficient system of free schools. The Constitution allows the Legislature to do both of these things.”

The Supreme Court directed the lower court to rule in favor of parents and the state.

The opinion, which was not unanimous, came in response to a lower court ruling in favor of education opponents challenging the new law, which the Legislature enacted in 2021 to establish the Hope Scholarship Program. The program allows parents to remove their children from traditional public schools and apply to the state for about $4,300, which can be directed to private school tuition, home education, and other pre-approved expenses.

More than 3,000 families had applied earlier this year, but weeks before school was set to begin, a circuit judge ruled the program unconstitutional and halted its operation. The decision sent parents scrambling to find alternatives in time for the start of the 2022-23 academic year.

On Oct. 6, the high court issued a one-page order finding the Hope Scholarship Program constitutional and allowed it to move forward. The opinion released Thursday was the full opinion.

Attorneys for one group of education choice supporters said the opinion shows what choice supporters across the United States have argued all along in making their case for giving parents the right to determine the best educational fit for their children.

“The West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals confirmed what state court after state court has found,” said Joshua House, an attorney with the Institute for Justice, a public interest legal organization intervening on behalf of two parents seeking Hope Scholarships for their children. “The constitutional requirement to provide for public schools is a floor, not a ceiling. West Virginia has to provide public schools, but it can give parents other options, too.”

One of the parents, Katie Switzer, whose child has a speech disorder that she thinks could be better addressed at a private school, praised the opinion.

“We're really excited to have this in writing,” Switzer said in a statement issued by the Institute for Justice. “This helps us have confidence moving forward to make decisions about the best education for our children.”

The opinion in favor of education savings accounts comes after 21 states established or expanded education choice programs last year.

Gateway Academy is an accredited private day school for grades 6-12 that supports students with high functioning autism. Established in 2005, the school operates in an engaging, motivating, and personalized way that helps students build confidence and prepare for the future.

Editor’s note: This first-person essay from Arizona mother Shana Lockhart was adapted from the American Federation for Children’s Voices for Choice website.

When my son was in kindergarten, we were told he was one of many individuals born with high functioning autism. While not an official medical term or diagnosis, high functioning autism is an informal term used to talk about those on an autism spectrum disorder who can speak, read, write, and handle basic life skills.

Like all people on the autism spectrum, those who are high functioning have a hard time with social interaction and communication. They don’t naturally read social cues and might find it difficult to make friends. They don’t make much eye contact or small talk. They can get so stressed by a social situation that they shut down.

My son started school in a self-contained public school classroom for children with communication disorders. When he reached third grade, he was mainstreamed into a general education class. We had our challenges in those years, but I know that my son’s teachers did the best they could.

Things changed when he hit middle school. Like many pre-teens, he was plagued by those raging middle school hormones. Students like my son tend to react differently than other students when they hit puberty.

His social interactions, already somewhat strained, became more difficult as he entered high school, where the campus was large and crowded. He became overwhelmed. It wasn’t long before he began refusing to go to school.

We were at a loss to know what to do. His school wasn’t working for him, but we didn’t know if there was an alternative. Then I heard about Gateway Academy, a private school in Scottsdale for students with high functioning autism. We went on a tour and loved everything we saw and heard.

The only problem was a big one: We couldn’t afford the tuition.

I will be forever grateful that we learned at that point about Arizona’s education choice scholarship program, specifically, the Empowerment Scholarship Account program. It allows parents to opt their children out of public district or charter schools and receive a portion of their public funding deposited into an account for defined uses, such as private school tuition, online education, education therapies and private tutoring.

We filled out the paperwork and were so happy to learn we were eligible. I enrolled my son in Gateway Academy, which he would not have been able to attend otherwise. He is so happy there. The setting allows him to be as independent as he can be, which is so important for his self-esteem.

Gateway sees challenges as learning opportunities. Unfortunately, some schools see students with autism and other disorders as lost causes. But these children are bright, and they have beautiful souls. They may learn differently, but they are capable of learning. They have as much potential as any other child.

Sadly, a lot of these kids fall through the cracks in public schools. My other two children found our zoned public school a good fit, but that was not the case for my youngest. His needs were different, but he had just as much right to a great education as the children who thrive in public schools.

I’ve learned since receiving the Empowerment Scholarship Account that Arizona’s education savings account program was the first of its kind in the nation. As of Sept. 24, student eligibility is expanded to universal, meaning all families in the state can utilize this amazing resource.

I believe that all parents should be able to provide the right educational fit for their children, despite their financial situation. I’m grateful to live in a state that is forward thinking when it comes to education choice.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jonathan Butcher, the Will Skillman Fellow in Education at The Heritage Foundation and a reimaginED guest blogger, and Madison Marino, research associate and project coordinator at the Heritage’s Center for Education Policy, appeared Wednesday on washingtontimes.com.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jonathan Butcher, the Will Skillman Fellow in Education at The Heritage Foundation and a reimaginED guest blogger, and Madison Marino, research associate and project coordinator at the Heritage’s Center for Education Policy, appeared Wednesday on washingtontimes.com.

Last summer, when Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey signed a law that made Empowerment Scholarship Accounts an option for all children in the state, special interest groups panicked.

Save Our Schools Arizona launched a referendum campaign, urging citizens to “vote for public schools” and support “our kids and our communities” by opposing the expansion. Yet SOS couldn’t gather enough signatures to put its proposal on the ballot.

It’s not that SOS didn’t have plenty of resources to qualify the measure. It’s just that families across the state think the accounts are what Arizona parents and students need.

“I’ve had so many conversations with neighbors and church friends, and it seems to come up everywhere,” said Annie Meade, mother of four and new account holder. “My neighbors who send their children to public school … are really happy for me to have more choices for my kids,” she said.

With Empowerment Scholarship Accounts, Ms. Meade and other participating families can use a portion of their child’s funds from the state K-12 education funding formula to purchase education products and services for their children. The money may be used to pay for online classes, textbooks, school uniforms, private school tuition, and more.

Ms. Meade will use accounts for three of her children and send her fourth to a charter school. The money will be used to pay tuition and expenses at a microschool, a small private school, along with curricular materials, music lessons and physical education classes.

To continue reading, click here.

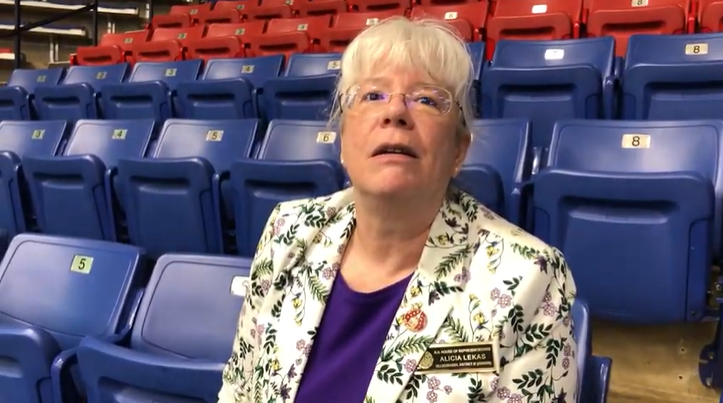

New Hampshire Rep. Alicia Lekas has filed a bill that would raise the cap on the state’s Education Freedom Account program from 300% to 500% of the federal poverty level, increasing the limit for a family of four to about $139,000.

Editor’s note: This article appeared today on newhampshire.bulletin.com.

Nearly two years after creating the “education freedom account” program, a growing number of New Hampshire Republicans are looking toward expanding who can access it.

During an Oct. 25 Bulletin/NHPR debate, Gov. Chris Sununu said he would support raising income caps on the program. In a Tuesday WMUR debate, he repeated that position. And one Republican lawmaker has already filed two pieces of legislation to do it.

“I would be open to expanding it if (lawmakers) want to do that,” Sununu said at a press conference Wednesday. “It’s because there’s such a high demand. We’ve created a product – we’ve created an opportunity for families, and more families than we anticipated want it.”

Any increase in income limits would be a transformative expansion for the program. And any effort to do so will likely reignite fierce ideological debates over the program – regardless of who controls the State House.

Created in 2021 as part of the two-year budget, the EFA program allows parents to access a portion of public education funds and use them toward nonpublic school expenses such as private school and home-schooling costs. Families that participate receive the per-pupil adequacy grant that would have been given to their local public school, which averages around $4,600 per student.

The program is currently targeted toward lower-income families: Families must demonstrate that they make below 300 percent of the federal poverty level in their first year. This year, that level is about $83,000 for a family of four.

Now, after a higher-than-expected initial take up, Republicans are proposing raising that income cap. A bill filed by Rep. Alicia Lekas, a Hudson Republican, would raise the cap from 300 percent to 500 percent of the federal poverty level – increasing the limit for a family of four to about $139,000.

To continue reading, click here.

Take Root Forest School’s mission is to provide outdoor learning experiences that inspire the curious mind, instill love and appreciation for nature, and nurture positive and holistic living.

DANIA BEACH, Fla. – While millions of American students sat in rows of desks under fluorescent lights, 40 kids in Take Root Forest School began their day in a state park on the edge of the Atlantic.

Their classroom: Tan sand. Blue water. Sea breeze rustling through cabbage palms. Over the next few hours, the students ages 6 to 12 climbed sea grape, hunted millipedes and, with their bellies on the beach, did their best impression of nesting sea turtles heading back to the surf.

Did your day start off that well?

When you learn outdoors, “you develop an appreciation for where you are,” said Take Root Forest School co-founder Christy Schultz. “You learn the plants. You learn the animals. You learn the subtleties.”

The students “grow to be stewards of where they live,” Schultz continued. “They respect where they live. They know the history. They become more aware of their surroundings, and of other people.”

This way of learning, she said, “transforms people.”

Take Root Forest School would be a sweet story even if it were as rare as a pond apple in what’s left of wild Florida. But as it happens, this humble homeschool enrichment program represents multiple education trends budding at once.

Located in the shadow of two of the country’s largest school districts – Broward and Miami-Dade – Take Root combines math, science, reading and other traditional subjects with hands-on, place-based activities.

Take Root is a prime example of the growth in outdoor learning and forest schools. It’s a testament to the spike in homeschooling. And it’s another vibrant example of the kinds of nontraditional education providers that are emerging as parental choice re-shapes the landscape.

It also happens to be taking root in Broward and Miami-Dade counties in the shadow of two of the biggest school districts in America, along with a fascinating list of other home-grown innovators like this one and this one and this one.

(For what it’s worth, no big urban district in Florida has seen a bigger jump in homeschooling than Broward; it had 10,412 home schoolers in 2021-22, up 151% over five years.)

For the (Barbados) cherry on top, Take Root’s founders also happen to be former public school teachers, a growing force in education entrepreneurship, especially in choice-rich states like Florida.

“Providing a sense of community was really important to me, but (in a traditional classroom) it was difficult to truly connect,” said Take Root’s other co-founder, Emily Feldman, who taught in public schools for seven years. “I felt disconnected from the students because my time was spent doing other things like grading or testing. I was limited in providing for the child’s individual needs.”

“I left thinking I’d never go back,” Feldman said.

But in a way, Feldman did go back.

On her terms.

She and Schultz both founded their own homeschool enrichment programs before joining forces to create Take Root in 2020. Their enrollment has more than doubled since then, and they now serve about 80 students, with an operation that includes eight teachers.

Their timing turned out to be perfect.

“When Covid hit, we blew up,” Feldman said.

Families wanted their kids to have the social interactions that were stymied by social distancing. Playing and learning outside turned out to be the short-term remedy and, for many families new to homeschooling, a pleasant eye opener about longer-term solutions.

Take Root students routinely meet in local nature parks, like the one where the kids were mimicking sea turtles. They also take more immersive trips to places such as Everglades National Park and Big Cypress National Preserve.

The teachers combine math, science, reading and other traditional subjects with hands-on, place-based activities. The school incorporates elements from Waldorf, Montessori and Reggio Emilia learning systems. And it makes no bones about its environmentalist bent.

Its mission, its website says, is to “provide outdoor learning experiences that inspire the curious mind, instill love and appreciation for nature, and nurture positive and holistic living.”

The result is about more than academics, narrowly defined.

“The students gain confidence,” said Shultz, who taught outdoor education for the state park system in California. “They also have to learn to play together, to cooperate, to work together.”

Jessica Goldman-Ortiz has two children at Take Root: Marco, 9, and Analia, 6.

A former public school teacher, Goldman-Ortiz wanted something different than a traditional school for her children, especially Marco, who was a bit reserved. So, five years ago, she enrolled Marco in Feldman’s program. It was the only pre-school she could find that would allow her to stay with her son until he was comfortable on his own.

Then, once Marco reached that stage, the school was good with him sitting under a nearby tree until he was comfortable enough to join his classmates. It took a few months, but Marco eventually did just that.

“He was given the space and time he needed,” Goldman-Ortiz said. “They’re respectful of the child.”

Take Root’s curriculum is comprised of multiple layers connected to nature and place, self and community, emerging not only from the rhythms of the season, but also from the innate wonder, curiosity and interests of children.

Parents have the option of sending their kids to Take Root either two or three days a week. A handful pay for academic services affiliated with Take Root using state-funded education savings accounts (ESAs).

Unlike traditional school choice scholarships, which are limited to private school tuition, ESAs can be used for tuition, therapies, tutoring, curriculum, and a wide range of other state-approved uses. Arizona recently made ESAs available to all families, and West Virginia’s new ESA is nearly as expansive. In Florida, they’re limited to students with special needs.

Many Take Root families would qualify for the state’s income-based scholarships (which along with the ESAs are administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog). But those scholarships don’t currently have the flexibility to be used for anything except private school tuition.

If more families could access ESAs, providers like Take Root would become even more popular. Along the way, ESAs would narrow access gaps to educational enrichment that are increasingly drawing attention, as highlighted by this new report from Tyton Partners.

Carolina Graciano said she chose Take Root because traditional schools are not a good fit for her child.

Luciana, 6, was born with a rare genetic disorder called 13q deletion syndrome, which has resulted in some developmental delays. She would have been too isolated in a self-contained special education classroom, Graciano said, but too far behind in an inclusive setting with a traditional focus on academics. Take Root had the balance Graciano wanted.

“When I take her in and drop her off, she says, ‘Okay! Bye!’” said Graciano, a stay-at-home mom whose husband juggles construction work and Uber Eats. “She is happy, and I know that she is learning.”

Beth Arnold said her son, Finnegan, 9, would not have been a good fit with traditional schools, either.

Finnegan is too fidgety for a typical classroom but thrives in environments where he is free to move. At one point, Arnold, a professional writer, enrolled him in a homeschool program that was focused on classical education.

Finnegan wasn’t a fan. But Take Root turned out to be to his liking. Among other upsides, the school frequently meets on the grounds of a historic home that has been converted into a museum. Exotic gardens and a wild monkey are part of the mix.

“It’s magical,” Arnold said.

When she was considering the best options for her son, Arnold said she asked herself: “Do I want him to have a childhood that he loves? Or do I want to prepare him for an Ivy League education?”

“I decided I wanted him to have a childhood that he loves.”