Editor’s note: Leslie Hiner, vice president of legal affairs at EdChoice, connects this U.S. Supreme Court case with the recent controversy over the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program and the interests of LGBTQ, lower-income and minority students, stressing that the position held by those who argue against financial support of religiously-affiliated schools is in direct conflict with precedent relevant in Espinoza.

Editor’s note: Leslie Hiner, vice president of legal affairs at EdChoice, connects this U.S. Supreme Court case with the recent controversy over the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program and the interests of LGBTQ, lower-income and minority students, stressing that the position held by those who argue against financial support of religiously-affiliated schools is in direct conflict with precedent relevant in Espinoza.

Attention parents, grandparents, and anyone responsible for the K-12 education of a child under the age of 18.

You are about to be impacted in a big way by people you probably don’t know. These people do not live in your neighborhood. They know virtually nothing about you or your children. But their decision will either respect your freedom to direct the education of your child, or it will limit or jeopardize your child’s educational opportunities.

The nine justices of the U.S. Supreme Court will deliver a decision sometime before the end of June in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue. The key issue in this case is whether parents who access school choice scholarships for their children may have the option to choose a religiously affiliated school for their children’s education.

In legal terms, the question before the Court is whether it is a violation of the Religion Clauses (Free Exercise, and Establishment) or Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution to invalidate “a generally available and religiously neutral student-aid program simply because the program affords students the choice of attending religious schools.”

How does this impact you?

The justices’ decision may create a huge new opportunity for expanded learning options for your child while protecting school choice options you may enjoy today.

In Montana, religiously-affiliated schools were banned from their school choice program. Parents who accessed scholarships from the program were denied the right to use those scholarships for their children at religiously-affiliated schools, and that’s why the parents sued the state. This is different from the famous Ohio voucher case, Zelman v. Simmons-Harris. In Zelman, the Court was asked whether it is constitutionally permissible for the state to include religiously-affiliated private schools in a voucher program. The Court said yes.

In Espinoza, the Court is asked whether it’s constitutional for the state to deny parents a free choice of schools, by excluding religiously-affiliated schools from a school choice program.

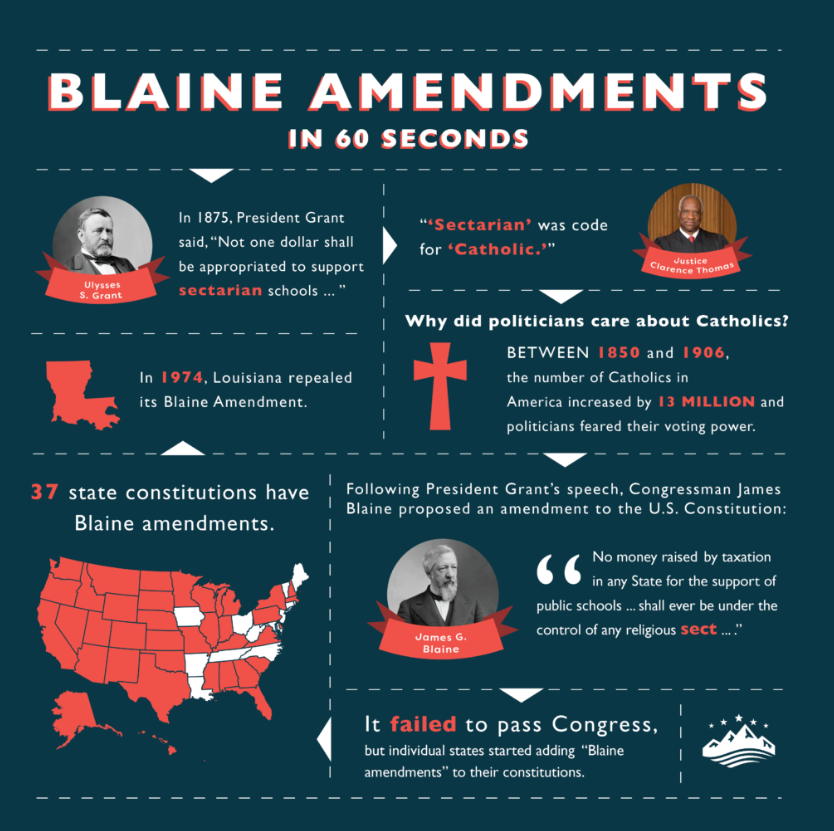

Espinoza could apply to you in two ways. If you live in a state with a Blaine Amendment that has no education choice, a favorable decision in Espinoza could energize legislators to enact school choice programs. If you live in a state with a Blaine Amendment but nonetheless have vouchers or similar programs, a favorable U.S. Supreme Court decision could remove all doubt as to the constitutionality of those programs and energize legislators to expand existing educational opportunities. Blaine amendments cast a heavy shadow over legislator confidence regarding constitutionality; if lifted, legislators will find a much clearer path toward expansive educational choice.

Religious freedom, guaranteed to each of us under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, plays an important role in education. A majority 66.4 percent of private schools are religiously affiliated, and 78 percent of private school students attend religiously-affiliated schools. Also, until the late 20th century, public schools operated like Protestant schools where children prayed and recited verses from the King James Bible.

I stand as a witness to this history, remembering the day it was my turn, in the sixth grade at my public school (not in the Bible Belt), to choose and deliver the scripture reading of the day. The absence of faith (or hostility toward religion) in today’s public schools has heightened parent interest in the virtues and offerings of religiously-affiliated schools, perhaps in part because today’s grandparents and some parents remember when faith in God – expressed casually in public schools – was as normal as saying the Pledge of Allegiance.

In Florida, religiously-affiliated schools that are part of the state’s tax credit scholarship program are under attack by some individuals who allege the schools’ religious beliefs are discriminatory and therefor, the schools should not be supported. This position is in direct conflict with U.S. Supreme Court precedent, which is relevant in Espinoza. When religiously-affiliated schools participate in student-aid programs, the state’s position regarding those schools must be neutral; discriminatory judgment regarding religious beliefs would violate the right to freely exercise those beliefs.

Thinly veiled attempts to compel scholarship groups or the state to violate neutrality toward religiously-affiliated schools is ill-considered.

During Espinoza oral arguments, Supreme Court justices were reminded that parents, not scholarship groups or the state, decide which school is the right fit for their children. Florida donors targeting religiously-affiliated schools should also be reminded that parents choose these schools; sometimes parents’ religious beliefs align with the schools, and sometimes parents choose a school for reasons that have nothing to do with religion. When corporate donors oppose the religious beliefs of those schools, they are punishing parents for choosing those schools, regardless the reason. Corporate donors have no requirement to fund scholarships, but when they stop funding scholarships to compel discrimination against those who hold certain religious beliefs, that’s wrong – and offensive to the First Amendment of the Constitution.

“Generally available and religiously neutral student-aid programs” fund parents on behalf of their children; the public benefit of these programs is directed to students through their parents. “Student-aid” programs do not fund schools. This principle has been clear since the Court’s 2002 Zelman decision. As Dick Komer, the Institute for Justice attorney representing parents in Espinoza, stated to the U.S. Supreme Court during oral arguments, “Zelman has already answered the question about who this program is aiding. It's not aiding the schools. It is aiding the parents.”

No person has asked the U.S. Supreme Court to force states to directly fund private schools like they directly fund public schools. Nonetheless, the Court chose to take the funding question to another level during Espinoza oral arguments.

Justice Breyer began the discussion with probing questions on whether a win for the parents in this case would also mean states would be forced to fund private schools directly along with funding public schools. Would a favorable decision mean states would violate the Constitution if they failed to directly fund both public and private schools?

An important, and unexpected, lesson emerged from this line of questioning.

Montana’s school choice program applies universally to all children in that state. And Justice Breyer’s questions rested solely on the principle that education funding applies to all children. He drew no distinction between education funding for children whose parents have higher income or lower income, or children who attend “A” rated or “F” rated schools, as is the case with many school choice programs.

As I listened to the debate, it struck me that a discussion on school choice funding that presumed funding would apply universally to all children was unusual. And it was refreshing.

Advocates of educational freedom often disagree about whether it is possible, or even desirable, for a state to provide scholarship programs for all children, regardless of income or circumstances. Yet, Supreme Court decisions on the constitutionality of educational choice apply to all children, not some children. This is a good precedent that all education reformers should follow.

The explosion of education alternatives illustrated in Step Up For Students’ Education Landscape document proves options are continuing to grow, with micro-schools being the latest alternative presenting real learning opportunities for children. As we continue to embrace innovative ways to educate the next generation of leaders, we should be mindful that all children have a right to learn.

If you notice that the sparkle of youth and joy of learning – that twinkle in your child’s eyes – has disappeared, Justice Clarence Thomas and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and their peers may be the last people you’ll think about when wondering if you’ll be able to access an education for your child that will rekindle that joy of learning. However, now is the time to pay attention to the Supreme Court, and to learn a powerful lesson about providing educational benefits to all children.

For more rederfinED posts about Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, click here and here.

Founders of the Oregon order Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, about 1859

Nearly a century ago, in 1925, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Pierce v. Society of Sisters. The state of Oregon had, by popular initiative, decided every child of school age would attend a “public” school to satisfy minimum educational requirements. Every family was to deliver its child to the state; St. Theresa and Johnson’s Private Academy could no longer satisfy the law of compulsory education.

Hence, the Sisters sued for their professional lives and the litigation rose to the federal judicial summit.

The Court in the 1920s was at the zenith of free market protectionism. Its holding in Pierce was technically a victory for those schools that were the initial plaintiffs, but the Court took the opportunity to broaden its message, stressing:

“[Oregon’s] act of 1922 unreasonably interferes with the liberty of parents and guardians … the child is not the mere creature of the State; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.”

The state, of course, remained secure in its capacity to impose a set of reasonable rules binding upon the private sector of schooling. But the parents remained master of the rest of the content of the child’s formal education; their sovereignty remains solid to this day, including the authority to choose the child’s formal educator. What seems worth adding to our focus is the court’s brief and ambiguous reference to the child’s own separate interest in receiving the parents’ choice: “The child is not the mere creature of the state.”

Children, of course, enjoy a cluster of legal rights, all of them protected both by and against their parent. The state has an obligation to interfere in case of serious abuse by parents. But the state itself also can become the abuser. A parent’s power to decide is of great value to the child, one that is protected by law as a personal right.

But compare, then, the status of the child of the poor with that of the well-off created by our systems of compulsory education. Given the protection of Pierce, the parent of the middle class on up is recognized both in law and fact as the one who nurtures and directs his destiny throughout childhood – that is, unless the parent is systematically and unnecessarily shorn of this authority and duty by the state itself. And so it is with the child of the poor in respect to school.

That boy or girl whose life experience is otherwise determined by adults who know and love him or her sadly has 13 years of early life determined by no human decision at all. “You live here; the law says that you go to school there.” The child is delivered to an institution that has never heard her name, to strangers who will have no reason to remember her, or her parent.

Worse, perhaps, little Jim or Susie is made witness to the near irrelevance of mother and father in the child’s own life story. The best they can do for the child is to play the sympathetic listener to sad stories about which they can do nothing. They “… have the right coupled with the high duty,” but they have been disabled by their own government.

Enter the Supreme Court – maybe.

The child’s own distinctive and separate constitutional right to the parents’ choice could well be considered by the justices as a core element of decision in the Montana school choice case, the latest chapter in the battle over the use of public funding for religious schools. Its emergence here as a clear element of our constitutional law would be a recognition of dignity for the low-income parent and a workable application of the 14th Amendment.

It seems especially appropriate midway through National School Choice Week to ask:

It seems especially appropriate midway through National School Choice Week to ask:

Can the use of state “Blaine Amendments” to prohibit publicly available funds from being used by parents at religiously affiliated educational options be considered discriminatory? And if so, does that discrimination violate a family’s right guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution to equal protections under the law?

Those are questions education choice advocates have been asking for nearly two decades. The issue came to a head last week when the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue.

Voucher opponents have managed to avoid these questions since 2006 when the Florida Supreme Court ducked the state’s “Blaine Amendment” arguments altogether in Bush v. Holmes. Opponents lucked out again when they seized the opportunity to pour millions into the Douglas County, Colorado, school board races to kill a voucher program that would have been a perfect test case for the U.S. Supreme court in 2017.

Voucher opponents may get lucky once again in 2020. It’s possible the U.S. Supreme Court will sidestep the issue and instead scold the Montana Supreme Court for thinking tax credits are functionally the same as direct tax dollars – a distinction the court already made in Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn in 2011.

And while Espinoza is an important case, some commentators have overblown its possible impact. Ian Millhiser, writing for Vox, and Jay Michaelson, writing for the Daily Beast, incorrectly claim that a victory for school choice supporters would be a “mandate” for states to fund religious schools and “starve” public schools. David Dayen, executive editor for the American Prospect, elevates the case to conspiracy level “brought … to undermine public education” by corporations seeking to obtain tax breaks from their donations to religious schools.

There is no corporate conspiracy theory, nor will Espinoza result in the starvation of public education, dozens of new voucher programs, or even a mandate to fund private religious schools.

At best, the U.S. Supreme Court simply will provide some consistency, or at least some guidance, on how all the various state Blaine Amendments can or cannot be applied to education. Florida is a great example of how Blaine Amendments have been inconsistently applied.

In 2004, the First District Court of Appeal ruled the state’s first voucher program, the Opportunity Scholarship, unconstitutional because it violated the state’s constitutional ban on direct or indirect aid to religious institutions. But the ruling was unsatisfactory because it failed to address the dozens of examples raised by voucher supporters. Examples included several legal cases in which churches benefiting from state or local programs did not violate Blaine.

In Koerner v. Borck (1958), the Florida Supreme Court ruled that a portion of a last will and testament allowing for land donation to Orange County for use as a park as long as a local church be granted perpetual easement to access the lake was constitutional because the benefit to the church also was a benefit to the general public.

In Southside Estates Baptist Church v. Board of Trustees (1959), the Court ruled that the use of public schools to hold private religious meetings did not violate the “No Aid” clause.

In Johnson v. Presbyterian Homes of Synod of Florida (1970), the Court ruled that tax credits for retirement homes were constitutional even if the retirement home was owned and operated by a religious organization. The Court stated: "A state cannot pass a law to aid one religion or all religions, but state action to promote the general welfare of society, apart from any religious considerations, is valid, even though religious interests may be indirectly benefited."

In Nohrr v Brevard County Education Facilities Authority (1971), the Court ruled that the government could issue bonds for facilities at religiously affiliated schools.

And in City of Boca Raton v. Gidman (1983), a case that dealt with publicly funded daycare at a religiously affiliated program, the Court stated: "The beneficiaries of the city's contribution are the disadvantaged children. Any “benefit” received by the charitable organization itself is insignificant and cannot support a reasonable argument that this is the quality or quantity of benefit intended to be proscribed."

These cases strongly suggest that programs created to benefit the general public CAN be provided by religious organizations, and that any benefit derived from the program to the church is merely incidental.

Florida’s Opportunity Scholarship Program voucher also forbade private schools from admitting students based on their religion and prohibited private schools from requiring students to take religious courses or attend religious services. The scholarships themselves didn’t cover the full cost of tuition, though the private schools had to accept the voucher as full payment. In other words, the private schools educated each child at a loss compared to private pay students. Voucher supporters argued that all these facts made education at a private religiously affiliated school functionally no different, as far as the “No Aid” clause was concerned, than medical services provided at a religiously affiliated hospital.

And so another question comes to mind: Why is it possible for individuals to use public programs to pay for medical services at religious hospitals, but not use public funds to pay for education at religious affiliated schools? The First District Court of Appeal failed to address this example entirely.

Voucher supporters pointed to the McKay Scholarships for children with disabilities along with the Florida Private Student Assistance Grant Program and Bright Futures Scholarships, which could be used at one of 23 private religiously affiliated colleges in Florida. The state Attorney General noted that the Legislature appropriated nearly $9 million to private religious universities in Florida in 2002.

Other examples include rent paid to churches for use as polling places, subsidized childcare and prekindergarten education at churches and religious schools as well as public funds to churches for the preservation of historic structures. The First District Court of Appeal ignored these examples, too.

The First District Court of Appeal defined the “No Aid” clause as prohibiting any funds being taken directly from the treasury to be paid to a religious organization, regardless of how the money arrived, even indirectly through choices made by parents offered scholarships. This ruling threatened many existing programs in Florida highlighted by the lawyers for the state.

Even Judge James R. “Jim” Wolf, who wrote a concurring opinion, argued the ruling endangered other programs unless arbitrarily confined to K-12 education, stating: "In order to avoid catastrophic and absurd results which would occur if this inflexible approach was applied to areas other than public schools, the majority is forced to argue that the opinion is limited to public school funding and article 1, section 3 may not apply to other areas receiving public funding."

In other words, the court had to distinguish K-12 education as being uniquely prohibited by the “No Aid” clause compared with other aid programs. Florida is not unique when it comes to Blaine. Other states have treated K-12 education as being distinct from other government programs in which churches may participate or benefit.

What conclusion can we draw from all of this?

Don’t expect Espinoza to be a major game changer. State legislatures still must create voucher programs and families still must choose schools for their children. All we can hope for is that the U.S. Supreme Court will provide some clarity in how Blaine Amendments can or cannot be applied.

Hopefully, we’ll learn that distinguishing K-12 education from other publicly beneficial programs is arbitrary and in error.