As late as the early 1990s, many Americans thought of going to see European films as desirably highbrow. European movies commanded 10% of the American box office. The problem with this was that European governments subsidized cinema, and the results were, well, uneven.

I recall going to see such a film titled “King Lear” as a university student only to be greeted by an old man sitting on a beach with the sounds of the waves coming ashore and (maybe?) someone whispering Shakespeare in the background. I decided that I had better ways to spend my cultural dollars, and so did many of my fellow Americans. European film viewership in the USA collapsed a few years later. Needless to say, there have been many fantastic European films, but the life lesson for me: never assume that the adjective European is a synonym for optimal.

All of which is prologue to the topic at hand, which is an opinion piece by Patrick T. Brown that effusively praises the European model of choice (whereby there is some but in which everyone must follow national academic standards and give national tests). Brown sums up his piece:

The parents’ rights and school choice movements aim to improve students’ academic, social and moral formation. That won’t automatically follow from a few policy wins. The new landscape for K-12 education will require the kind of studied, technocratic approach that doesn’t necessarily garner applause on a debate stage but is essential to making the permanent and lasting change conservatives would like to see.

A “studied, technocratic approach” is what we (allegedly) receive in American school districts. Democratically elected boards hire “expert” superintendents, principals and (usually) “certified” teachers. Sadly, we awake every day from our technocratic dream to a reality of widespread illiteracy, civic ignorance and philosopher-kings coronated by regulatory capture. If a “studied, technocratic approach” were the solution to our K-12 problems, we wouldn’t have them.

Over the years, school choice advocates have learned the hard way what not to do, or have we? Louisiana, for instance, enacted a heavily regulated school voucher program in 2008 that places onerous admission and curriculum restrictions on participating private schools, as well as a requirement to administer the state annual assessment. Accordingly, most of the state’s private schools chose not to participate, and many that did participate had falling enrollments before the advent of the program. When scholars published an academic evaluation of the Louisiana program, it was the first program to show negative results.

A basic flaw of technocracy is that the proponents imagine virtuous rule by disinterested philosopher-kings, but we wind up with politicized messes. For instance, we have witnessed a decline in the American charter school movement wherein incumbent operators team with charter opponents to throttle charter school growth. The proponents claimed that they were ensuring “quality,” but the correlation between technocracy and a vanishingly small number of charter seats is strong, quality non-existent.

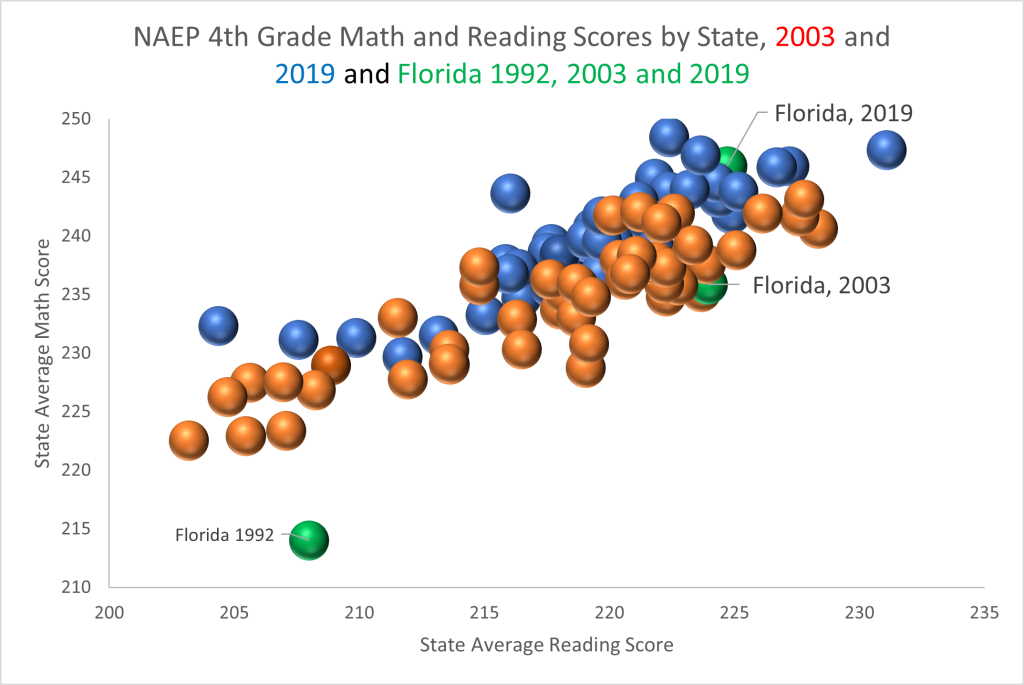

Finally, we have home-grown in the USA examples of choice programs delightfully free of European-style technocracy spurring broad academic improvement. Florida began private choice programs in 1999. Florida choice programs have a testing provision but allow schools to choose from a menu of assessments. This helps ensure a much higher private school participation rate than in Louisiana, which mandated the state test. It also ensures a greater diversity of schools.

Henry Ford once quipped that buyers could have a Model T in any color they liked, as long as it was black. Florida has had no need to offer assistance for families to choose any school they want, as long as they follow state academic standards and tests.

As Douglas Carswell (a wise European) wrote in The End of Politics “The elite gets things wrong because they endlessly seek to govern by design in a world that is best organized spontaneously from below. They constantly underrate the merits of spontaneous, organic arrangement, and fail to recognize that the best plan is often not to have one.” We should view European pluralism as an undesired floor rather than the highest possible ceiling.

One of the recent projects of OIDEL, the Geneva-based NGO mentioned in my last post, has been to coordinate researchers from across Europe in a project to identify and then apply indicators for how national education systems respond to the concerns of parents, including but not limited to their desire to choose the schools that their children attend. It’s called IPPE: Indicators for Parental Participation in Compulsory Education.

I will just summarize IPPE’s conclusions; you can review the whole study and interact with it here. There is also a book with detail on methodology and results country-by-country, published in French in April and in English in September; look for it on https://www.amazon.fr/ in both languages by searching for the first author, Felice Rizzi.

The study makes a distinction between individual and collective rights of parents. In the first category are:

“The category of ‘collective’ parental rights largely refers to parents’ rights to participate in formal structures organised [sic] by the education system.”

Through working closely with the European Parents’ Association and other official and unofficial sources of information, the study was able to draw detailed – though inevitably preliminary – comparative conclusions about the situation with respect to these rights in seven countries of the EU, and then collected less detailed information from eight others.

I’ll focus just on the first of the rights identified. The survey asked two questions: Are there varied educational projects? And are there financial resources in place allowing parents to choose schools "other than those established by the public authorities?" The phrase in quotes is from the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

For each of the countries studied, an answer is offered to both questions, as to the others, and a (rather clumsy) numerical score assigned; thus Belgium receives a score of 100 on the right to choose, Spain a 75, and Italy and Portugal each a 60. I would myself rate Italy considerably lower, based on my work there.

The conclusions of the study call for funding of non-public schools and for measures to protect their autonomy from over-regulation.

The study does not compare the EU countries with the United States, and such a comparison would require a refinement of the questions: There is now extensive variety among schools in the US, more so than in some EU countries, because of the spread of charter schools and – less happily – because of the quality differences which are more marked in the US than in most of the EU. Choice among charter and district schools is essentially free of cost. On the other hand, unlike most EU countries, the US does not provide cost-free choice of schools with a religious character, which millions of parents desire so strongly that they pay for it themselves.

For this and other reasons, the narrative portion of the IPPE report seems to me more useful than the attempt to attain precision by assigning numerical values to the different countries on the various questions. Perhaps the greatest value, however, is simply the effort to reach agreement on indicators derived from commonly-recognized parental rights. As these indicators are used by other and more detailed studies, they will make it possible to advance the discussion of parental rights in useful ways.