While leaders of some religious organizations that provide childcare and prekindergarten believe their students could benefit from President Joe Biden’s $1.85 trillion Build Back Better bill, they worry that a nondiscrimination provision in the social policy bill could disqualify children who utilize their programs from such benefits.

While leaders of some religious organizations that provide childcare and prekindergarten believe their students could benefit from President Joe Biden’s $1.85 trillion Build Back Better bill, they worry that a nondiscrimination provision in the social policy bill could disqualify children who utilize their programs from such benefits.

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Orthodox Union are part of a coalition of faith-based groups that are lobbying to have parts of the legislation rewritten to prevent them from having to turn families away who want to enroll in their centers.

In an action alert, Catholic leaders urged their advocates to write to Congress about the potential impact of the bill’s current language, which would give certificates to parents to choose their providers. The funding method would classify faith-based providers as recipients of federal financial assistance.

Such a move would place the providers, who have historically been exempt under current funding methods, under requirements of certain federal laws, namely the Americans with Disabilities Act and Title IX, which forbids sex discrimination.

“As a general rule, Catholic schools and most nonpublic schools purposefully avoid federal financial recipient status, because it triggers a whole host of federal regulatory obligations with which nonpublic schools are not currently required to comply,” Michael B. Sheedy, the executive director of the Florida Conference of Catholic Bishops, wrote in a letter last week to U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, Republican of Florida, according to the New York Times.

Catholic leaders say the bill also might require the church to obey laws that govern Head Start programs, even if their programs don’t offer Head Start.

“Head Start nondiscrimination provisions to faith-based providers could, for instance, interfere with faith-based providers’ policies or practices that acknowledge any difference between males and females, such as sex-specific restrooms, or with their preferences for hiring employees who share the providers’ religious beliefs,” according to the Conference’s bill analysis.

Leaders also fear the Americans with Disabilities Act provisions would force providers to pay for expensive renovations to facilities and in some cases, churches.

“Although, of course, Catholic schools and other Catholic entities endeavor greatly to be accessible to all persons, especially persons with disabilities, there are, nevertheless, many cases where new renovations would be required that are cost-prohibitive at present,” according to the analysis.

Faith-based providers make up a substantial part of the nation’s child care services, with 53% of families who used center-based care choosing them for their children, according to a 2020 survey by the Bipartisan Policy Center. Trust was the main reason parents cited for choosing their provider.

“The Archdiocese of Miami serves over 2,600 students in pre-kindergarten, over half of which would be classified as coming from a high-poverty background,” said Jim Rigg, superintendent of schools for the Archdiocese of Miami. “If non-public schools are excluded from this bill, many new families will be drawn toward programs that are free of cost, regardless of their quality. We know we do an excellent job of educating young children and believe that families should make the best choice for their child’s education regardless of their economic status.”

Jennifer Daniels, the Conference of Catholic Bishop’s associate director for public policy, said religious protections have been in place for years and have allowed faith-based providers to maintain their religious identity and offer religious instruction.

“They’ve changed the way that program is going to be designed,” she said. Previous scholarship programs for low-income families allowed them to choose religious schools, but the new law would force those schools to comply with the same rules as secular schools thereby eliminating that choice for those parents.

“Catholic teaching tells us that parents are their child’s first and primary educator, so they should have a say in where their child gets to go to school and what type of school that is,” said Daniels. “If they choose a religious school for their child, they should have the ability to do that.”

The podcast “99% Invisible” featured a fascinating story of an impromptu shrine and the unexpected benefits it’s brought.

The podcast “99% Invisible” featured a fascinating story of an impromptu shrine and the unexpected benefits it’s brought.

Dan Stevenson of Oakland, California, lived in a neighborhood beset with crime and drugs. An open space near his home was being used in 1999 as a site for illegal garbage dumping. Frustrated, Dan decided to clean up the space, purchase a statue of the Buddha, and place it on the site.

Strange things were afoot at the Circle K from that point forward. The trash dumping stopped. People began to leave offerings of various sorts at the statue. After being identified as the person who erected the statue, Dan started finding gifts left for him at his front door.

Daily prayer vigils began, and the space surrounding the statue was spruced up. Most interesting of all, recorded crime in the area dropped by 82%.

Erecting a shrine on public property might offend some sensibilities, but those in the area continue to appreciate it, and you can still visit it today.

University of Notre Dame law professors Margaret F. Brinig and Nicole Stelle Garnett may have found an echo of the Oakland Buddha in their statistical analysis between Catholic schools and neighborhood crime rates. Specifically, they examined data over time from Chicago and found that areas with closed Catholic schools experienced greater crime.

Interestingly, the analysis found no relationship between charter schools and social disorder.

A great deal more research lies ahead, but one of the aims of empowering families in education is to treat religious groups in a neutral fashion rather than actively discriminating against them.

American K-12 policy has addressed the question of religion through a series of follies. Public schools initially were used as an instrument of the Protestant majority to “assimilate” Catholic immigrants. The public schools were religious (Bible readings and all) but only in a fashion generically acceptable to Protestants. If you happened to be a Catholic, Jew, Buddhist, Muslim, Agnostic or Atheist, well too bad.

The Ku Klux Klan muscled through a law requiring public school attendance in Oregon in the 1920s. The Klan aimed to turn Oregon Catholics into “real Americans” (insert author gagging noise about here). The United States Supreme Court struck the law down. The productive course at that point (or any future point) would have been to embrace pluralism in education as is common in Europe.

As Winston Churchill once noted, Americans always can be relied upon to do the right thing but only after all other possibilities have been exhausted. Instead of “to each his own” in a fashion common in Europe, American public schools essentially banished religion from the curriculum in the decades following the Oregon episode.

The U.S. had precisely zero states in 2019 in which 50% or more of eighth-grade students could read at proficiency. I can live without these schools teaching religion, or their secular equivalents. If more kids could read proficiently, we would have hope for a future in which more adult Americans could think.

We may, however, have lost something very important in actively discriminating against religious schools, and it may stretch well beyond test scores. Government neutrality toward religious groups, neither favoring nor discriminating against them, creates a way forward in which the American people can shape the education space according to their needs and values.

We’ve exhausted all the other possibilities. It’s time to get this right.

Berkeley Law professors John C. Coons, left, and Stephen Sugarman, circa 1978.

On this episode, Tuthill continues his conversation with education choice pioneer Stephen Sugarman of Berkeley Law School. The two discuss Sugarman’s 2017 article in the Journal of Law and Religion in which Sugarman argues that prohibiting faith-based schools from becoming charter schools is unconstitutional under the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause.

Sugarman’s argument that it’s unconstitutional to exclude faith-based organizations from participating once a state has chosen to fund alternative education options was echoed earlier this year in the landmark Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue. On the podcast, he reviews the history of two notable U.S. Supreme Court cases, Locke v. Davey and Trinity Lutheran v. Comer, and how their precedents laid the groundwork for the Espinoza decision.

"There should be some room (for education choice funding) between what is forbidden by the Establishment Clause and what is required by the Free Exercise Clause. Funding choice (does) not violate the Establishment Clause.

EPISODE DETAILS:

· Sugarman’s 2017 article on the constitutionality of faith-based charter schools

· Locke v. Davey and Chief Justice Rehnquist’s explanation of the “play-of-the-joints” between the Establishment and Free Exercise clauses of the Constitution

· How teacher union hostility toward charter schools has caused the public to mistakenly think they’re private rather than public schools

· How a faith-based organization can operate a charter school by state policy while continuing to practice religious observances outside of classroom time

LINKS MENTIONED:

Sugarman: Is it unconstitutional to prohibit faith-based schools from becoming charter schools?

podcastED: SUFS President Doug Tuthill interviews education choice icon Stephen Sugarman – Part 1

You can watch Part 1 of Tuthill’s interview with Sugarman here.

Editor’s note: This month, redefinED is revisiting the best examples of our Voucher Left series, which focuses on the center-left roots of school choice. Today’s post from June 2016 tells the story of civil rights activist and school choice pioneer Mary McLeod Bethune, who started a private, faith-based school for African-American girls in 1904 that became known as Bethune-Cookman University.

How fitting: The choiciest of school choice states may soon be represented in the U.S. Capitol by the statue of a school choice pioneer.

A state panel nominated three legendary Floridians for the National Statuary Hall last week, but the only unanimous choice was Mary McLeod Bethune. The civil rights activist and adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt is best known for founding the private, faith-based school that became Bethune-Cookman University.

Assuming the Florida Legislature gives the Bethune statue a thumbs up too, more people, including millions of tourists who visit the hall each year, may get to hear her remarkable story. And who knows? Maybe they’ll get a better sense of the threads that tie the fight to educational freedom in Bethune’s era to our own.

With $1.50 to her name, Bethune opened the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls in 1904. There were public schools for black students in early 1900s Florida, but they were far inferior to white schools.

Bethune’s vision for something better was shaped by her own educational experience.

She attended three private, faith-based schools as a student. She taught at three private, faith-based schools before building her own. In every case, support for those schools, financial and otherwise, came from private contributions, religious institutions – and the communities they served. Backers were motivated by the noble goal of expanding educational opportunity. Black parents ached for it. That’s why, in the early days of her school, Bethune rode around Daytona on a second-hand bicycle, knocking on doors to solicit donations. That’s why her students mashed sweet potatoes for fund-raiser pies, while Bethune rolled up the crust.

Failure was not an option, because failure would have meant no options.

Goodness knows, I’m no expert on Mary McLeod Bethune. But given what I do know, I think she’d be amazed at the freedom that today’s choice options offer to educators. More and more teachers, especially in choice-friendly states like Florida, are now able to work in or create schools that synch with their vision and values – and get state-supported funding to do it.

Bethune was forever hunting dollars to keep her school afloat, and it wore her down. In 1902, she asked Booker T. Washington for money. In 1915, she asked philanthropist and civil rights advocate Julius Rosenwald for money. In 1920, she made a pitch on the letters page of the New York Times. (All of this can be found in “Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World,” a nice collection of Bethune’s writing.)

In 1941, Bethune even asked FDR. “I need not tell you what it has meant in Florida to try to build up a practical and cultural institution for my people,” she wrote to the president. “It has taken a wisdom and tact and patience and endurance that I cannot describe in words.”

“We are now in desperate need of funds,” she continued. “My nights are sleepless with this load upon my heart and mind.”

I can’t help but wonder what a superhero like Bethune could have done, had Florida had vouchers and tax credit scholarships a century ago. I don’t mean to dismiss the inequity in funding for choice programs – it’s real, and it deserves more attention – but inequity is relative. The funding streams available for low-income students today would have allowed Bethune to park the bike, forget the pie crust and focus on her core mission.

It would also have allowed her to rally more to the cause.

Bethune, who initially hoped to be a missionary, understood how much education and faith are intertwined for so many parents, and that it doesn’t make sense to pit public against private, or one school against another.

In 1932, she weighed in on a feud between state teacher colleges with an essay that foreshadows the all-hands-on-deck views of many of today’s choice supporters. She referenced the massive number of truant African American students and the “pitiful handful” that graduate from high school. “Unfriendly rivalry was never more needless, never more inexpedient among the schools of Florida than just now,” Bethune wrote.

The same could be said for K-12 education today.

Somehow, though, Bethune managed to end her essay on an up note, with an appeal to common ground:

Florida faces a new day in education. Grim as the picture appears today, it is not nearly so bad as it was just a few years hence, and the aspect is rapidly changing for the better; a veritable miracle is transpiring before the eye. The day for which many warriors now aging in the service have longed, the day for which they have prayed and sweat drops of blood – that new day of the hoped-for better things is approaching. With the scent of victory in the nostril, may every agency redouble its zeal; with jealousies forgotten, with the spirit of competition thrust aside, may every organization and individual unite under the banner of One Common Cause, the grim battle against ignorance and vice, and carry the issue to a glorious victory.

Editor’s note: This February marks the 43rd anniversary of Black History Month. redefinED is taking the opportunity to revisit some pieces from our archives appropriate for this annual celebration. The article below originally appeared in redefinED in March 2017. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis visited the school featured in this article while on the campaign trail.

Angela Kennedy’s decision to quit being a public school teacher was driven by a steady drip, drip, drip of frustration.

Dr. Angela Kennedy was a 14-year veteran of public schools when she left to start her own private school. She had been a classroom teacher and instructional coach, and had also coordinated curriculum compliance for English language learners. “I wanted parents and students and teachers to have another option,” she said.

In her view, teaching had become too scheduled and scripted, with new teacher evaluations rewarding conformity more than effectiveness. Cohort after cohort of low-income kids continued to stumble and fall, while people far from classrooms continued to impose mandate after mandate. Her passion for teaching began to fade.

Kennedy considered becoming an administrator, so she could attempt reform from within. But ultimately, she took a leap of faith. After 14 years in Orange County Public Schools, she did what educators in Florida increasingly have real power to do: She started her own school.

Deeper Root Academy began three years ago, with three students in Kennedy’s home. Now it’s a thriving PreK-8 with 80 students and nine teachers, including seven who, like Kennedy, once worked in public schools. Most of the students are black, and 80 percent are from in or near Pine Hills, a tough part of Orlando that drew President Trump to another private school this month.

“It was that back and forth, thinking about where I could be the most impactful,” Kennedy said. "Would it be to stay and try to start a change? To try to deal with a mammoth system? Not likely that I’m going to get very far ... "

"But what I could do is give people an option. And that’s where this school came from. I wanted parents and students and teachers to have another option.”

"But what I could do is give people an option. And that’s where this school came from. I wanted parents and students and teachers to have another option.”

Kennedy had options because parents had options.

Florida offers one of the most robust blends of educational choice in America, which is why Education Secretary Betsy DeVos gives it a nod. Forty-five percent of Florida students in PreK-12 attend something other than their zoned district schools, with a half-million in privately-operated options thanks to some measure of state support.

Charter schools, vouchers, tax credit scholarships and education savings accounts are all opening doors for Florida students. With far less fanfare, they’re doing the same for teachers.

“In my school,” Kennedy said, “I have the liberty to do what’s best for my kids.”

At Deeper Root, she and her staff are guided by the theory of multiple intelligences. Parents like it. Enrollment is rising fast from word-of-mouth referrals.

About 50 students attend with help from choice programs – tax credit scholarships for low-income students, McKay vouchers for students with disabilities, and Gardiner Scholarships, an education savings account program for students with special needs such as autism. The tax credit and Gardiner programs are administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.

It’s unclear how many of Florida’s 50,000-plus private and charter school educators once taught in district schools. But it’s easy to find examples of teachers who migrated from one sector to another (see here, here and here). And it wouldn’t be surprising, given the growth in choice programs, that the number of crossover teachers is rising too.

Kennedy said colleagues in district schools frequently call, wanting to know what it’s like to teach in a school that she herself shaped. Many are as frustrated as she was, and intrigued by the new possibilities. It’s highly unlikely, she said, that a massive system compelled to be “uniform” can ever meet the needs of every teacher. Just as with students, some teachers won’t fit the mold.

“I don’t think that anyone had malicious intent,” Kennedy said of the regulations that guide the state system. “I think they’re trying to get a structure in place that’s uniform.”

But “teachers are not robots.”

Deeper Root moved from Kennedy’s home, to a storefront in a shopping plaza, to now, the leafy campus of a trim, modern, Presbyterian church. At a Black History Month event, students in crisp uniform shared their knowledge with peers and parents in the church auditorium. One expounded on the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution. Several gave a presentation about the slave ship Henrietta Marie. A fourth grader, poise far beyond his years, recited portions of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”:

Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, "Wait."

Kennedy considered a charter school, but decided the regulations were still too much. More importantly, she wouldn’t be able to create the faith-based environment she and her parents want.

Deeper Root students take Bible class and go to chapel every Wednesday. But their curriculum is not faith-based. The school teaches Florida state standards, which are based on Common Core. Many of Kennedy’s students arrive after stints in Florida public schools, and most will return there for high school. “I want them prepared,” she said.

Preparation includes life lessons too. Students grow cabbage and broccoli in planter boxes made from old shelving. They take field trips to Publix to learn how to read labels and choose healthy foods. They visit restaurants so they can order from the menu and leave a tip.

While choice can empower teachers, it’s still not easy, Kennedy said. Going solo was scary, particularly because she had no experience with the financial side of school operations. At one point, a bad business relationship drained her investment and forced her to take out loans.

The learning curve was painful, but compelled her to quickly learn the essentials. Now, Kennedy said, she can advise other educators who want to make the leap – and serve as proof it can be done.

Kiwie, 14, is an eighth-grader who has endured years of turbulence in public schools because of his LGBTQ status. The only school where he briefly felt accepted was a faith-based school in Jacksonville where most of the students use school choice scholarships.

DAYTONA BEACH, Fla. – Kids walking past the classroom windows would point and yell, like kids in a zoo. “THAT’S A GIRL!” They’d grab his chest and groin, to see if the rumors were true. All day, he’d avoid the middle school restroom, to avoid boys sliding under the stall. “Dyke.” “It.” Maybe it’d have been less hellish if students were his only tormentors. One time, Kiwie got the courage to raise his hand for help, only to have the teacher enunciate the stab. “Yes, ma’am?”

“It felt,” Kiwie said, “like my heart was squished.”

Kiwie is 14. He’s an eighth grader. He faces an uphill battle to get to ninth. No child’s learning experience should be like this. Yet for Kiwie, it’s like this, year after year.

His only reprieve: Two months in a Christian “voucher school.”

***

Kiwie is slim, athletic, stylish. Round-ish frames and a black T-shirt pair with a puff of honey-brown hair. He likes lasagna and Chick-fil-A. He likes Odell and Conor McGregor. His dad is an amateur boxer. His ethnic blend – Italian, Croatian, African-American — turn heads. Maybe it’s no surprise he wants to be a model or a boxer.

Kiwie grew up in Jacksonville, 90 minutes north of Daytona. He struggled from the start in public schools. By the time he was diagnosed with dyslexia and ADHD, his mom, Stella, said he’d already been held back in second grade. By then, he hated school. (For security reasons, Stella requested she and Kiwie’s last names not be used.)

Meanwhile, his gender identity was emerging. He never liked girl’s clothes. Never liked pink. “I didn’t know why,” he said. “I just knew it wasn’t me.”

By fourth grade, he was asking teachers to call him Kiwie, a pet name his father gave him. By fifth grade, he was becoming enraged when they botched the pronouns. “They didn’t care,” he said. “They thought I was just confused.”

Rage alternated with depression. At home, Kiwie would bang his head into the wall. He ran a pocket knife across his wrist.

In sixth grade, Kiwie googled “trans.” “I said, ‘Yeah, that’s me.’ ”

When he felt slighted, Kiwie began walking out of class. He flipped a table. Knocked a computer off a desk. One time, police were called. A few times, he was “Baker Acted.”

“I felt like the world was crumbling on us,” Stella said. “Why can’t they just accept him?”

***

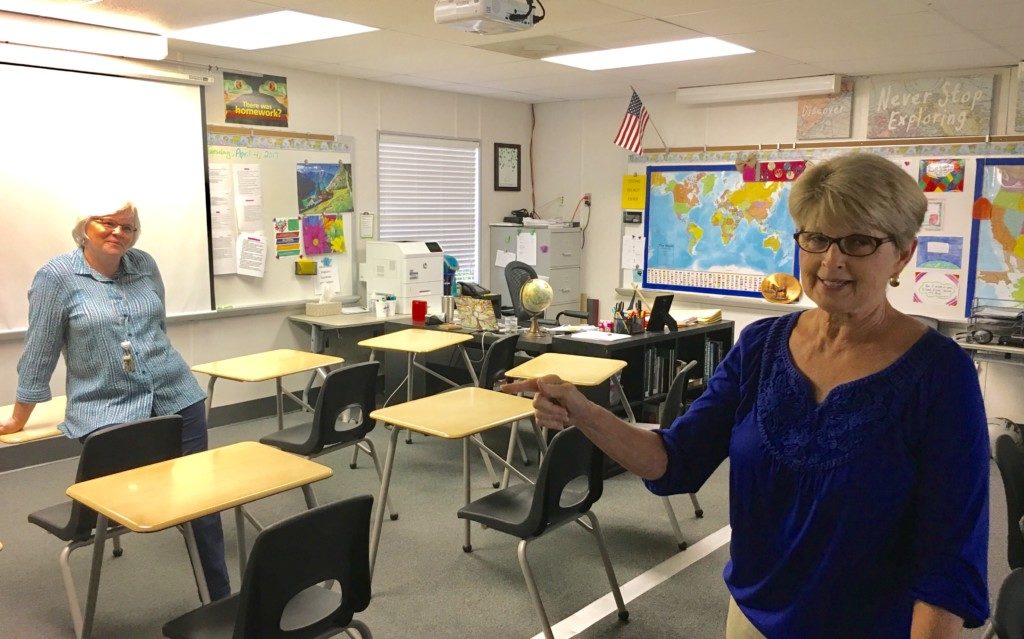

School choice can't work in rural areas? Tell that to Judy Welborn (above right) and Michele Winningham, co-founders of a private school in Williston, Fla., that is thriving thanks to school choice scholarships. Students at Williston Central Christian Academy also take online classes through Florida Virtual School and dual enrollment classes at a community college satellite campus.

Levy County is a sprawl of pine and swamp on Florida’s Gulf Coast, 20 miles from Gainesville and 100 from Orlando. It’s bigger than Rhode Island. If it were a state, it and its 40,000 residents would rank No. 40 in population density, tied with Utah.

Visitors are likely to see more logging trucks than Subaru Foresters, and more swallow-tailed kites than stray cats. If they want local flavor, there’s the watermelon festival in Chiefland (pop. 2,245). If they like clams with their linguine, they can thank Cedar Key (pop. 702).

And if they want to find out if there’s a place for school choice way out in the country, they can chat with Ms. Judy and Ms. Michele in Williston (Levy County’s largest city; pop. 2,768).

In 2010, Judith Welborn and Michele Winningham left long careers in public schools to start Williston Central Christian Academy. They were tired of state mandates. They wanted a faith-based atmosphere for learning. Florida’s school choice programs gave them the power to do their own thing – and parents the power to choose it or not.

Williston Central began with 39 students in grades K-6. It now has 85 in K-11. Thirty-one use tax credit scholarships for low-income students. Seventeen use McKay Scholarships for students with disabilities.

“There’s a need for school choice in every community,” said Welborn, who taught in public schools for 39 years, 13 as a principal. “The parents wanted this.”

The little school in the yellow-brick church rebuts a burgeoning narrative – that rural America won’t benefit from, and could even be hurt by, an expansion of private school choice. The two Republican senators who voted against the confirmation of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos – Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Susan Collins of Maine – represent rural states. Their opposition propelled skeptical stories like this, this and this; columns like this; and reports like this. One headline warned: “For rural America, school choice could spell doom.”

A common thread is the notion that school choice can’t succeed in flyover country because there aren’t enough options. But there are thousands of private schools in rural America – and they may offer more promise in expanding choice than other options. A new study from the Brookings Institution finds 92 percent of American families live within 10 miles of a private elementary school, including 69 percent of families in rural areas. That’s more potential options for those families, the report found, than they’d get from expanded access to existing district and charter schools.

In Florida, 30 rural counties (by this definition) host 119 private schools, including 80 that enroll students with tax credit scholarships. (The scholarship is administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog.) There are scores of others in remote corners of Florida counties that are considered urban, but have huge swaths of hinterland. First Baptist Christian School in the tomato town of Ruskin, for example, is closer to the phosphate pits of Fort Lonesome than the skyscrapers of Tampa. But all of it’s in Hillsborough County (pop. 1.2 million).

The no-options argument also ignores what’s increasingly possible in a choice-rich state like Florida: choice programs leading to more options.

Before they went solo, Welborn and Winningham put fliers in churches, spread the word on Facebook and met with parents. They wanted to know if parental demand was really there – and it was.

But “one of their top questions was, ‘Are you going to have a scholarship?’ “ Welborn said. (more…)

Angela Kennedy’s decision to quit being a public school teacher was driven by a steady drip, drip, drip of frustration.

Dr. Angela Kennedy was a 14-year veteran of public schools when she left to start her own private school. She had been a classroom teacher and instructional coach, and had also coordinated curriculum compliance for English language learners. “I wanted parents and students and teachers to have another option,” she said.

In her view, teaching had become too scheduled and scripted, with new teacher evaluations rewarding conformity more than effectiveness. Cohort after cohort of low-income kids continued to stumble and fall, while people far from classrooms continued to impose mandate after mandate. Her passion for teaching began to fade.

Kennedy considered becoming an administrator, so she could attempt reform from within. But ultimately, she took a leap of faith. After 14 years in Orange County Public Schools, she did what educators in Florida increasingly have real power to do: She started her own school.

Deeper Root Academy began three years ago, with three students in Kennedy’s home. Now it’s a thriving PreK-8 with 80 students and nine teachers, including seven who, like Kennedy, once worked in public schools. Most of the students are black, and 80 percent are from in or near Pine Hills, a tough part of Orlando that drew President Trump to another private school this month.

“It was that back and forth, thinking about where I could be the most impactful,” Kennedy said. "Would it be to stay and try to start a change? To try to deal with a mammoth system? Not likely that I’m going to get very far ... "

"But what I could do is give people an option. And that’s where this school came from. I wanted parents and students and teachers to have another option.”

"But what I could do is give people an option. And that’s where this school came from. I wanted parents and students and teachers to have another option.”

Kennedy had options because parents had options.

Florida offers one of the most robust blends of educational choice in America, which is why Education Secretary Betsy DeVos gives it a nod. Forty-five percent of Florida students in PreK-12 attend something other than their zoned district schools, with a half-million in privately-operated options thanks to some measure of state support.

Charter schools, vouchers, tax credit scholarships and education savings accounts are all opening doors for Florida students. With far less fanfare, they’re doing the same for teachers.

“In my school,” Kennedy said, “I have the liberty to do what’s best for my kids.” (more…)

Ken Brockington was one of the best teachers I ever had. Cerebral. Serious. Always dapper. In the mid-1980s, he inspired me and countless others in AP American History. Time has fuzzed the details, but I can’t forget Mr. B’s yellow suit, or his red pen. “Interesting,” he’d write in the margins of my papers, next to yet another half-baked idea, “but keep thinking.”

Me and Mr. B. Ken Brockington taught me AP American History in high school. Little did I know that he'd become a school choice pioneer.

The teenage me had no clue, but Mr. B was a pioneer. In the late 1960s, he was on his way to law school when a brief gig as a GED teacher detoured him into the teaching profession – and on to a new frontier. In Jacksonville, Fla. he became one of the first black teachers in integrated public schools. To get a sense of the challenge, consider many of those schools were named after Confederate generals, and one was named after the founder of the KKK. That’s where Mr. B taught me.

Today, at 68, Brockington is again surfing history. After 30 years as a teacher and principal in one of Florida’s biggest school districts, he’s now the academic dean of a private school. Cornerstone Christian seeks to uplift disadvantaged kids, and it’s able to serve them thanks to the Florida tax credit scholarship, the nation’s largest private school choice program.

Educators like Ken Brockington are part of another sea change in American education. At its heart, the school choice movement is fueled by the same drive for educational opportunity that spurred Brown v. Board of Education, and there’s no state where choice is becoming mainstream faster than Florida. Despite much-publicized skirmishes, like the lawsuit against tax credit scholarships and the NAACP attack on charter schools, choice is here to stay.

Educators like Ken Brockington are part of another sea change in American education. At its heart, the school choice movement is fueled by the same drive for educational opportunity that spurred Brown v. Board of Education, and there’s no state where choice is becoming mainstream faster than Florida. Despite much-publicized skirmishes, like the lawsuit against tax credit scholarships and the NAACP attack on charter schools, choice is here to stay.

Take it from a history teacher.

Parents aren’t going back, Brockington said: “They’re beginning to understand the power of choice.”

Teachers aren’t going back either. Mr. B (now Dr. B) said many of his colleagues are exceptionally skilled, but constrained in conventional schools. “Choice will allow them to get outside the box,” he said.

As fate would have it, I am again in Mr. B’s orbit.

I work for Step Up For Students, the nonprofit that helps administer the tax credit scholarship and hosts this blog. This year, the program is serving 95,000 students, including 7,000 in Jacksonville and 229 at Cornerstone. When work brought me to Jacksonville last month, I got to thank Mr. B in person for teaching me. As a bonus, I got to learn from him again.

The lawsuit that aims to kill the scholarship program is led by the state teachers union. Brockington was a union member; at one time, he said, he was the local vice president. But he had no qualms about switching from public school to private school more than a decade ago.

At the time, Cornerstone contracted with a social service agency to teach some of the city’s most “at-risk” students – students with, as Mr. B described it, “a suitcase of problems.” Teen moms. Dads in jail. A long list of learning disabilities. Today’s students, while not as disadvantaged as those in the past, still face so many of the hurdles that come with poverty.

Mr. B said this is where he can best help them. Their academic outcomes aren’t where they should be, yet, but they’re getting the right mix of toughness and compassion, he said: “They’ve been written off. But now there’s light at the end of the tunnel.” (more…)

Civil rights activist Mary McLeod was a school choice pioneer, opening a private, faith-based school for African-American girls in Daytona in 1904. The state of Florida may honor her with a statue in the U.S. Capitol. (Image from Wikimedia Commons.)

This is the latest in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

How fitting: The choiciest of school choice states may soon be represented in the U.S. Capitol by the statue of a school choice pioneer.

A state panel nominated three legendary Floridians for the National Statuary Hall last week, but the only unanimous choice was Mary McLeod Bethune. The civil rights activist and adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt is best known for founding the private, faith-based school that became Bethune-Cookman University.

Assuming the Florida Legislature gives the Bethune statue a thumbs up too, more people, including millions of tourists who visit the hall each year, may get to hear her remarkable story. And who knows? Maybe they’ll get a better sense of the threads that tie the fight to educational freedom in Bethune’s era to our own.

With $1.50 to her name, Bethune opened the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls in 1904. There were public schools for black students in early 1900s Florida, but they were far inferior to white schools.

Bethune’s vision for something better was shaped by her own educational experience.

She attended three private, faith-based schools as a student. She taught at three private, faith-based schools before building her own. In every case, support for those schools, financial and otherwise, came from private contributions, religious institutions – and the communities they served. Backers were motivated by the noble goal of expanding educational opportunity. Black parents ached for it. That’s why, in the early days of her school, Bethune rode around Daytona on a second-hand bicycle, knocking on doors to solicit donations. That’s why her students mashed sweet potatoes for fund-raiser pies, while Bethune rolled up the crust.

Failure was not an option, because failure would have meant no options.

Goodness knows, I’m no expert on Mary McLeod Bethune. But given what I do know, I think she’d be amazed at the freedom that today’s choice options offer to educators. More and more teachers, especially in choice-friendly states like Florida, are now able to work in or create schools that synch with their vision and values – and get state-supported funding to do it. (more…)