The Forte family of Pensacola, Florida

On this episode, senior writer Lisa Buie talks with Jacquelyn Forte of Pensacola, Florida. Forte is the mother of four children, including three who attend a Catholic school on state education choice scholarships.

Her oldest child, Jude, initially received the McKay Scholarship for Students with Disabilities, which merged this year with the state Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities scholarship. That program offers parents spending flexibility in the form of education savings accounts, which in addition to paying for private school tuition and fees, can be used for tutoring, curriculum, therapies not covered by insurance, and other pre-approved expenses.

Forte loves the flexibility that the new scholarship offers Jude, including speech therapy he’s been afforded since age 2. Jude is now thriving and recently qualified for his school’s gifted program.

Forte expressed her gratitude for a change in state law that makes siblings of scholarship students automatically eligible for the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options. The teacher-turned-homemaker called it a “godsend” that gives her and her husband, who works in pharmaceutical sales, financial breathing room while sending all three children to the same Catholic school that offers them a sense of community along with great academics and a solid faith-based foundation.

A proponent of any change to the program that would expand eligibility, she acknowledged how it could benefit her other children as well. Any leftover funds could be applied to extra-curricular activities, unforms and school supplies.

https://nextstepsblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/JaqForte_mixdown-final.mp3

EPISODE DETAILS:

CREATE Conservatory celebrated the 101st day of school with a “101 Dalmatians” theme featuring lesson plans that tied the arts to historical happenings 101 years ago. Students made their own newspapers to show what they learned, soaking the papers in pans of tea to give them the look and feel of old newsprint. The school will move to the site of a former minigolf center after Thanksgiving.

Once in a great while, the hook for an article — that is, the thing that caught the journalist’s eye in the first place — winds up being the least compelling aspect of the entire story.

This does not mean that the hook in this case is any less cool. At a glance, what’s better than a private school in rural central Florida moving its campus seven miles to the site of the former Adventure Cove, a derelict miniature golf course?

Or that the school’s founder intends to preserve at least a couple of the holes for student recreation as well as on-campus festivals and fundraisers.

“You know, make a hole-in-one, win a car?” says Nicole Duslak, a former Orange County public school teacher and the dynamo founder behind CREATE Conservatory. Meaningful pause. Eyebrow raised. “Know anybody who’d like to donate a brand-new car?”

But it’s what CREATE does and has been doing with rousing success since opening to students in Leesburg (about an hour’s drive north of Disney World) in 2020 that steals this show: The K-8 nonprofit employs arts integration to teach STEM subjects. And it sounds like Leonardo da Vinci-level genius.

Ever get a song stuck in your head in an endless loop? Who hasn’t? Silly brains. But suppose instead of driving you batty, that annoying tune taught you the periodic table of the elements? Or the arrangement of bones in the human skeleton? Or the order of mathematic operations, so you no longer got stumped by your friends’ annoying what’s-the-answer posts?

“We hear a song at a wedding or in the elevator or a department store, and we pick it up without really trying,” Duslak said. “It’s still a part of us decades later. We all do that, so we’re teaching science that way, a way that it becomes part of our students.”

CREATE Conservatory founder Nicole Duslak, front, with parent Candi DeMers

It’s not just singing — although the idea of a school as a real-life musical has its charms. CREATE introduces concepts through crafts, art, model-building, clay-molding, dancing, script- and narrative-writing, drafting graphic novels, and acting … to name a few of the school’s arts-immersive activities.

CREATE’s curriculum can’t be bought off the rack or downloaded from a website. Instead, Duslak and her staff of five are constantly writing it, and rewriting it, drawing inspiration from “Schoolhouse Rock!,” the Saturday morning series of short videos that musically covered themes including grammar, science, mathematics, history, and civics. (Admit it: You’re humming “Conjunction Junction” right now.)

Creativity rules the academic day. State standards ensure rigor.

Terri Harper, a mental health counselor and Duslak’s longtime friend, sends sons Levi, 10, and Landon, 8, to CREATE on a Florida Tax Credit Scholarship and a Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities. Both are administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog. She is amazed and gratified by the changes in both.

“My kids, who have never really been too into art,” she says, “now they’re asking for sketch books and sketching pencils and things like that, because they're discovering this whole different side of themselves. Wow. Yeah, it's great, it's really great.”

Kim Levine, a Leesburg-based partner with Core Legal Concepts — a graphic design shop for lawyers — became CREATE’s first corporate sponsor four years ago, well before the school opened its doors.

“She draws people in,” Levine says, "and I think that's great. Maybe the parents feel that, or the perspective parents, when they go on a tour, and they meet Nicky and hear her talk.

“She's got a ton of experience and assorted degrees, so she's got credibility, but she's so warm and loving, and she's so committed to this idea.”

Meeting Duslak and a few of her key allies for the first time at a reception designed to recruit community and corporate support (Levine was the only visitor), it wasn’t long before Levine felt like a billionaire panelist on “Shark Tank” blown away by the contestant’s pitch. “I love this idea,” she said. “Let’s do something together.”

That something became two full scholarships, worth about $6,500 each — one named for Stuart Levine, Kim’s late husband — and graphic arts support from Core Legal.

“One of the first things I thought was, I wish I'd had the school when I was a kid,” Levine says, “because I needed that sort of simulation. … Yeah, I just love it. I just thought,” This is perfect, I want to be involved.”

Duslak’s methods may sound exotic. They certainly are mold-busting. But wait.

“The modern education system has told our bravest and most creative thinkers to sit down and be quiet,” Duslak said. “And that's problematic, right? … I don’t want to sit still for eight hours a day in a desk, and I’m a fully grown adult who has complete control over my functioning.”

CREATE students do not sit at desks. Because there are no desks. Instead, there are beanbags and bounce-on exercise balls and couches and ample floor space. And windows. Oh, so many windows.

“Occasionally,” Duslak said, “I'll have a kid out to go over and just stand and look out the window, and I'll think, ‘There is no way they have any clue what's going on right now.’ Then I'll call on them and they're right with me; they just have to move to think. … They just have to look at something else.”

This is no free-for-all, Duslak said. “It's just about fostering an environment where kids can be themselves and we can honor everything about them that makes them, them.

“We have a lot of structure. … It's about slow down and get to know them and appreciate them for who they are as people.”

If a chef’s proof is in the pudding, an educator’s proof is in the testing. And the CREATE Conservatory students are crushing it: Youngsters have arrived testing nearly two years behind grade level on the Iowa Test of Basic Skills and finished their first academic year testing three years above grade level.

Area parents are taking note. From seven students when CREATE opened to 28 and a waiting list in two years is the stuff of dreams-in-the-making.

So, about the miniature golf course, the conversion and partial preservation of which brought Duslak to our attention. It’s not

CREATE Conservatory student Amalie Weaver

exactly like a shut-down putt-putt course screams, Put a school here! There are bridges and boulders shaped from concrete, after all. And streams and a jungle temple that once had a waterfall running through it and a downed airplane stuck in one corner.

Those are a lot of attractive nuisances to demolish and haul away, at substantial expense, even with teams of volunteers swinging sledge hammers and loading wheelbarrows — $16,000 for the temple and airplane alone.

But Duslak had a best friend in her brother, David Slocum, a resort golf club professional who was working toward PGA status when he died in 2002.

“David has been and continues to be a huge motivator in my life, even though he's not here anymore,” Duslak said. “So, when we found this property and when all this came to be, I just sort of felt like that was his way of being involved in the process.”

Preserving a hole or two will honor both Slocum and the happy memories of Adventure Cove nostalgics. “It’ll be sort of an homage to what the property was,” Duslak says.

The 2.5 acres will be nice for Duslak’s long-range plans. She hopes to add a high school, and a theater for performing arts. For the moment, however, she’s happy to be moving into the attractive Key West-style two-story bungalow that once housed the business’ offices, storage, and concessions. The plan is to be fully relocated after Thanksgiving break.

The going, just now, is financially difficult, as the early days often are for many startups and pioneering entrepreneurs. But Duslak is dug in.

“I will be the greeter person at Walmart on my nights and weekends, if that's what I have to do,” she said, “because I will not let this fail.”

That’s the best hook of all.

Hope, Caleb and Mary Hayes attend school on Florida's Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jonathan Butcher, Will Skillman Fellow in Education at the Heritage Foundation and a reimaginED guest blogger, and Jason Bedrick, a research fellow at the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy, appeared Saturday on orlandosentinel.com. You can listen to reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s podcast with Emily Hayes here.

As a mother of five children, Emily Hayes knows that every child has different needs. And she is keenly aware that these needs change over time.

This means life at home must change as children grow and, so does life at school — or wherever a child is learning.

This is a lot for any parent to handle. Especially parents of children with special needs.

As a mom living in Port St. Lucie, though, Emily had access to K-12 education savings accounts — formerly known as Gardner Scholarships and now called Family Empowerment Scholarships for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA).

These flexible scholarship accounts allowed Emily to choose different education products and resources at the same time for her children, from textbooks to personal tutors and beyond.

The accounts “have the flexibility to change with the kid,” Emily says, which has allowed her and her husband to specifically meet each of their children’s needs with personal tutors and therapy services and in recent years, a private school. “Each of [my children] has so many different needs. And it changes year-to-year as they progress year to year,” she says.

Two of her children are on the autism spectrum; another has complications related to brain and spinal development.

Emily’s children are among the 25,000 Florida students using these accounts. Another 84,000 are using vouchers to attend K-12 private schools, and 80,000 more attend private schools using scholarships funded by charitable contributions to scholarship-granting organizations, such as Step Up for Students.

With the breadth and depth of Florida’s private education landscape, the state is ranked first in a new Heritage Foundation survey of all 50 states and Washington, D.C., in the areas of education choice, academic transparency, low regulations on schools, and a high return on investment for taxpayer spending on education. In three of the four categories examined Florida ranks among the top three nationwide.

For education choice, Florida ranks third behind Arizona and Indiana. All three states offer families numerous pathways to choose the learning environment that works best for their children. Studies find that education choice policies lead to higher levels of achievement and educational attainment as well as greater civic participation and tolerance, and lower levels of crime.

But for parents to choose well, they need information. That’s where the Sunshine State truly shines, earning first place for academic transparency. Earlier this year, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill that allows parents to see a list of materials that teachers are using in classrooms and view the catalogue of school library books. State officials also approved a proposal saying teachers and students must be free to engage in debates in class, but no one can be compelled to believe ideas, such as the idea that — because of their skin color — individuals deserve blame for past actions committed by others.

The high degree of transparency enables parents to hold schools accountable directly. Instead of trying to ensure quality through top-down regulations and red tape, Florida relies on bottom-up accountability, which is why it ranks second in the nation for regulatory freedom.

Schools and teachers have a high degree of freedom to operate as they see fit, within the boundaries set by age-appropriateness and civil rights laws, and parents provide accountability through their freedom to choose the schools that work best for their kids.

Florida lawmakers’ embrace of choice, transparency and regulatory freedom has produced one of the highest returns on investment in the nation, ranking seventh nationwide. While keeping spending within reason, Florida has steadily improved its performance on the National Assessment for Education Progress over the past two decades, rising to 17th nationwide in its combined fourth-grade and eighth-grade math and reading scores.

As for Emily, she says that “the kids are thriving.” The school aligns with her family’s values and has provided “targeted therapy” for each child — a winning combination.

But it took more than a single assigned school to help her and her children find success.

“Not every school is going to meet the needs of every kid,” Emily says, which makes education choice essential.

If an assigned school anywhere in the country is not meeting a child’s needs, parents should point to Florida and ask their lawmakers, “Why can’t we have more options, too?”

After 23 years, Florida’s oldest K-12 private school scholarship is no more.

After 23 years, Florida’s oldest K-12 private school scholarship is no more.

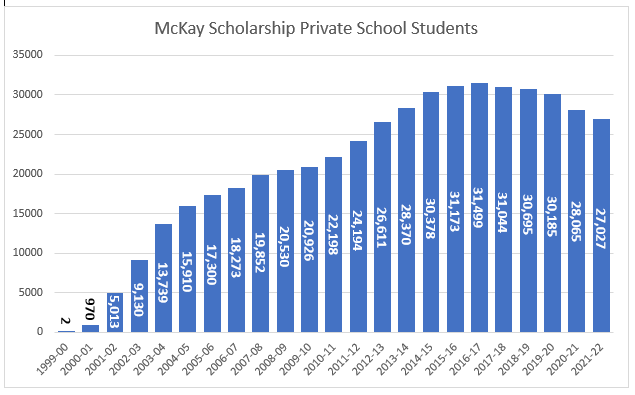

The McKay Scholarship finished its final year funding $257.3 million in scholarships for 27,027 students with special needs according to a new report released by the Florida Department of Education this week.

The McKay Scholarship began as a pilot program in Sarasota with just two students in 1999. Named after state Sen. John McKay, R-Bradenton, who sponsored the bill, the Florida Legislature in 2000 passed the program into law as a statewide scholarship for students with special needs.

The scholarship was initially capped at 5% of the statewide enrollment of students with special needs in public schools. This cap was later lifted, allowing all students with special needs to be eligible for a scholarship so long as they attended a public school in the prior year, or were entering kindergarten.

The program remained Florida’s only K-12 scholarship without an enrollment or funding cap.

Over the last 23 years, the McKay Scholarship funded more than $3 billion worth of scholarships for 483,082 students. State law also allowed thousands of students with special needs to transfer to different public schools if they didn’t want to attend a private school on scholarship.

In all, more than a half million students were helped by the program.

The McKay Scholarship, Florida’s largest K-12 scholarship program from 2000-2008, was Florida’s second K-12 private school scholarship program after the Opportunity Scholarship, which also began in 1999 and ended in 2006 after the Florida Supreme Court ruled it violated the state constitution. It had the distinction of being the only K-12 private school scholarship program not sued by the state’s teacher union and statewide school district associations.

The program officially came to an end July 1. Students on McKay last year were allowed to continue their scholarship through the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities.

Former McKay Scholarship students will not count against the FES-UA’s enrollment cap.

An education savings account for students with special needs allows Eilise White to learn at home while taking band and two other classes at a nearby Catholic school where her father, a teacher at Florida Virtual School, serves as band director.

On this episode, reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie talks with Sherry White, a former district middle school teacher who taught near Ocala and now homeschools her 16-year-old daughter, Eilise.

Born with autism and other medical conditions, Elise needed traditional physical and occupational therapies, but each session caused tantrums and screaming. A Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities allowed the family to afford tae kwon do as an alternative therapy, while a supportive Catholic school offered unbundled educational services.

It was great because she could take that class and get the benefits she would have had from physical therapy, like strengthening her core, learning to use her hands and feet, but without being in that strict physical therapy context. It was something she wanted to do.

EPISODE DETAILS:

Carrie Brazer, pictured upper right with staff and students, has made it her life’s mission to find alternative treatments to heal the autistic child while heightening community awareness through her fundraising efforts with national and community organizations in support of autism research and awareness.

Editor’s note: Visit autismsocietyofthekeys.com for more information on the Carrie Brazer Center for Autism and cbc4autism.org for more on the Carrie Brazer School for Autism.

For 23 years, the Carrie Brazer Center for Autism in Miami has served students on the autism spectrum and others with neurodiverse conditions. During that time, Brazer, a Florida-certified special education teacher with a master’s degree in special education, noticed that families from the Florida Keys were driving as much as three hours to come to the area for therapies and other services.

To better serve those families, Brazer opened a small office in Tavernier, an unincorporated area in Key Largo with a population of 2,530. When a charter school campus across the street became available, Brazer seized the opportunity to open the school’s second campus on the half-acre lot.

The new campus opened last year with six large classrooms in a 5,000-square-foot building. The school has a large indoor play area with lots of swings. The weather usually is pleasant enough for the students to eat lunch outdoors.

“It’s just gorgeous,” Brazer said. “It’s very beachy and homey and airy and spacious.”

The center began small, with 10 students in its first class. Brazer’s goal is to expand that number to 100 when classes resume in August, keeping in mind the school’s goal to maintain a 5-to-1 student-teacher ratio.

In addition to classes for students with autism, the school also offers a separate program for siblings who are neurotypical.

“That way, parents don’t have to go to two different schools,” she said.

The addition of a new location for autism services came at a good time for the state. The COVID-19 pandemic caused delays in getting diagnoses and treatment by forcing providers to shut down in-person services and transition to telehealth appointments. Meanwhile, the state is proposing new rules that will make it more difficult for children to get therapies during the school day.

Brazer and her staff identify as a “positive discipline school,” one of the only in Florida for students on the autism spectrum. The Positive Discipline model, derived from the work of psychologists Alfred Adler and Rudolph Dreikurs, teaches children, teachers, staff and parents to be encouraging to each other and to themselves. It’s a school model designed to teach everyone to have a role that creates a sense of belonging and significance, with every relationship being nurturing and deeply respectful.

Brazer and her staff identify as a “positive discipline school,” one of the only in Florida for students on the autism spectrum. The Positive Discipline model, derived from the work of psychologists Alfred Adler and Rudolph Dreikurs, teaches children, teachers, staff and parents to be encouraging to each other and to themselves. It’s a school model designed to teach everyone to have a role that creates a sense of belonging and significance, with every relationship being nurturing and deeply respectful.

Programs include an intensive early intervention program for 2- to 5-year-olds, a full day school program for elementary, middle and high school students aged 5-22, and adult day training featuring life skills and vocational training for students over 21. Music therapy as well as community-based instruction that includes swimming and horseback riding are part of the curriculum.

And because part of the school’s philosophy is that there is a child inside of every individual, regardless of his or her age, students enjoy a playground built by the Miami Dolphins after Hurricane Irma.

To make the school accessible to more families, it accepts state scholarships, including the Family Empowerment Scholarships for Students with Unique Abilities, which beginning July 1 will include former McKay Scholarship students. The school also accepts all insurance so children can receive behavior therapy, allowing them to work closely with behavior assistants during or after school to improve life skills and reduce behavior problems.

Reflecting on the school’s first year of operation, Brazer counts building a strong community base among her successes. The school has partnered with the Autism Society of the Keys, a nonprofit organization that helps families with resources and hosts meetings and other events at the school.

Looking toward the summer, Brazer found it challenging to find field trip locations because of the lack of indoor venues in the Tavernier area, such as bowling alleys, skating rinks and bounce houses.

“Summer camp was a real test of what we’re up against,” she said. “We found a couple of good things that have pools and parks, aviaries and swim the with the dolphins.”

To attract more families, the school will host an open house in June. Parents will be able to tour classrooms and meet school staff while their children enjoy hot dogs and face painting.

“We really want to get the word out and let people know we’re here,” Brazer said.

Editor’s note: This student profile first appeared on Step Up For Students’ Marketing blog.

Editor’s note: This student profile first appeared on Step Up For Students’ Marketing blog.

Dylan Quessenberry was 15 when he walked up a flight of stairs for the first time.

It was 20 steps, linking two floors at his school. But for Dylan, who has cerebral palsy, that staircase was more than just a route to the cafeteria at Learning Independence For Tomorrow (LiFT) Academy, a private K-12 school that serves neurodiverse students.

Those 20 steps were part of his journey to what he called “independence,” something he sought when he joined the school in the fifth grade on a Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (formerly the Gardiner Scholarship).

“It was a defining moment in his life,” LiFT Principal Holly Andrade said. “A massive milestone.”

Dylan, now 18 and a senior at LiFT, recently recalled that day as if he were still standing at the summit, sweaty and spent and filled with a sense of accomplishment that few can understand.

Like a marathoner on race day, Dylan woke that morning knowing the years of work he put in with his physical therapist, Valerie, were about to pay off.

“Those stairs,” he thought, “are mine!”

And they were, one arduous step at a time. Leaving his walker at the bottom and cheered on by students who were involved in afterschool programs, the school staff still on campus and Valerie, Dylan made the ascent. He pumped his fists in the air when he finished.

It took nearly half an hour.

“It was amazing,” he said. “I was like, glorified.”

To continue reading, click here.