True North Classical Academy in Miami is ranked No. 14 in the state for elementary schools and No. 29 for middle schools by U.S. News & World Report. Ninety-five percent of students score at or above proficient in math and 92% score at or above proficient in reading.

Editor’s note: This post reflects the content of a news release issued by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

In a new report from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools and The Harris Poll released Wednesday, parents reveal that they want more and better school options with 93% believing that one-size education doesn’t fit all and 86% wanting options for their children other than the district-run school they are assigned to attend.

This is something Florida school choice advocates already know. In the sunshine state, enrollment in education choice programs, including charter schools, has steadily increased over the last two decades.

Enrollment in public charter schools has continually risen since their inception in 1996. The schools now serve more than 11% of the public school student population. An estimated 47% of PreK-12 students attended a school of their choice during the 2017-18 school year.

The poll gathered feedback from parents of school-age children across the U.S. and found that:

“Parents are a powerful voting bloc in our country, and those currently serving or seeking political office would do well to listen to them,” said Nina Rees, president and CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

“This report shows education has increased dramatically in importance as a voting issue to parents. Education has often taken a back seat as a priority issue in elections, but it appears this is no longer the case, and rightfully so.”

Osceola County School Board member Jon Arguello continues to defend American Classical Charter Academy in St. Cloud as a worthy example of school choice for families despite findings that the school is nearly $800,000 in debt, has failed to meet payroll and operating expenses, and is facing eviction.

A Florida charter school that closed after a judge upheld the school board’s decision to revoke its charter has found an unlikely ally – a school board member.

Osceola County School Board member Jon Arguello, whose vocal support for education choice sometimes puts him at odds with his fellow board members, was the only board member who voted against terminating the contract of American Classical Academy. He said the vote was hypocritical.

“If the roles were reversed, they’d be looking to close us,” he said after listening to a parade of parent testimonials about how their children had gone from struggling to thriving after moving to the charter school. “They’re outperforming our schools, and now we’re going to take away an option for parents who have a school that’s outperforming ours. It seems incredible that we’re bringing this up.”

School board members voted 4-1 on April 5 to revoke the charter upon the recommendation of Superintendent Debra Pace, who cited financial problems. In a letter to the board, she said expenditures at the end of 2021 were more than $600,000 in the red. The school also lost $178,000 in December, with the loss rising to more than $182,000, causing the school not to meet its obligations of funding payroll and operating expenses.

The school also was behind in its lease payments and already in the middle of an eviction process.

Pace said that even though the school would have 90 days to resolve the issues, the action had to be taken before the end of the 2021-22 school year to comply with state law.

“We don’t like to do a closure ever, but there’s a process that’s involved,” she said. “This was not a decision I took lightly, but I don’t want to wait until June and have an eviction go into place.”

Even before the vote was taken, school founder Mark Gotz prepared to file an appeal. Administrative Law Judge Lynne Quimby-Pennock sided with the school district.

"The clear and convincing evidence demonstrates that the school board had sufficient basis to move for the termination of ACCA’s (American Classical Charter Academy’s) charter pursuant (to a section of state law)," Quimby-Pennock wrote in a 65-page order.

As examples of the issues in the case, the judge wrote that only 10 of the school’s 28 teachers were certified and that students were not properly provided exceptional-student education services "because there was no certified ESE teacher providing instruction on campus for August and most of September 2021."

Leaders for the charter school have promised to appeal the judge’s decision.

“We believe that we shall prevail,” according to a statement on the website titled “Gross injustice dealt to the students of Osceola County.”

Meanwhile, the parents of the 330 students who attended the school have scrambled to find other options as district schools opened Wednesday. Several spoke in support of the charter school during the April 5 meeting.

“Please don’t shut us down; help give us a hand,” said Kathryn Leslie, whose five children attend the American Classical Charter Academy. She said she chose the school because she liked its classical approach to education.

“Our students matter, and the school is worth saving,” she said.

Arguello said he plans to write a letter to Florida Commissioner of Education Manny Diaz Jr., a former charter school employee and former state senator who supported education choice, to see if anything can be done to make it easier for charter schools like American Classical Charter Academy to stay open and offer choices to families.

“This school is providing a valuable service to the community,” Arguello said. “We need charter schools to survive.”

He said the school, which has been operating only three years, got hit by the coronavirus pandemic shortly after it opened. Pointing to staffing shortages and budget issues plaguing district schools in his county, he said the charter school is being penalized despite facing the same challenges.

He called school board members’ claims during the board meeting that the governing board members of the charter school are from out of state irrelevant.

“If we didn’t get money from the government, we could not have our doors open now,” he said. “We need some crusaders and some lawyers who are willing to stick their necks out for these kids.”

Billed by its founders as “the world’s first virtual reality charter school,” Optima Classical Academy is expected to open in August with 1,300 students in grades 3-8. The academy intends to expand classes up to 10th grade for the 2023-24 school year.

Editor’s note: Erika Donalds, education choice advocate and president and CEO of the Optima Foundation, spoke earlier this week with reporters at the Daily Signal about the intersection of virtual education and classical education. You can read reimaginED’s interview with Donalds here.

Classical education is a trusted model of learning. Virtual reality is a new technology still being fully developed. Despite the view of some that the two could be in conflict with each other, Erika Donalds disagrees.

“Classical education … is content-based, and [virtual reality] is the perfect way to deliver that content,” says Donalds, president and CEO of the Optima Foundation.

Donalds established the Optima Foundation, which has grown to be a network of charter schools, to give parents better education options for their children. After the pandemic, Donalds realized that some parents and students preferred an at-home model, but online education fell short of providing students with a strong education.

Virtual reality allows teachers and students to meet live in a virtual space from home, she says.

Through virtual reality, children “actually go to Mars, they go to the lunar landing, and they’re there when it happens in virtual reality,” Donalds says.

Donalds joins “The Daily Signal Podcast” to discuss the ways in which virtual reality can add to and expand classical education.

You can listen to the podcast here.

All students at Woodmont Charter School, one of four schools whose renewal application was denied by the Hillsborough County School Board, are considered economically disadvantaged. The school is managed by Charter Schools USA, based in Fort Lauderdale.

Charter schools in Florida will have a smoother path following Gov. Ron DeSantis’ signing on Thursday of two bills related to charter school operation.

House Bill 225 requires school boards to make a final decision about the future of charter schools at least 90 days prior to the end of the school year. Had the measure been in place last summer, a last-minute decision on the part of the Hillsborough County School Board to close four charter schools a month before classes were scheduled to resume would have had a different outcome.

The school board ultimately renewed the charters after Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran threatened to withhold funding for the district for what he considered a violation of the state’s 90-day notice rule. Charter schools are automatically renewed if board fail to follow the procedures outlined in the new law.

The new law also includes a provision that would require sponsors to approve or deny charter school mergers within a 60-day period.

The bill received bipartisan support, with Democrats on the House Early Learning and Education subcommittee joining Republicans in a favorable vote.

Senate Bill 758 establishes a statewide approval board for applications and an institute for charter innovation. The new law will:

According to language in the bill, “It is the intent of the Legislature that charter school students be considered as important as all other students in this state, and to that end, comparable funding levels with existing and future sources should be maintained for charter school students.”

Rep. Alex Rizo, R-Hialeah, who co-sponsored the House version of the bill with Rep. Fred Hawkins, R-St. Cloud, said the bill would put charter school students on equal footing with those who attend traditional district schools and help Florida continue to be the national school choice leader.

The new laws go into effect July 1.

St. Petersburg College recently announced the opening of its third collegiate high school, a charter school situated on its downtown St. Petersburg campus, that will allow students to simultaneously earn high school diplomas and associate of arts degrees at no cost to students and families.

Like their counterparts nationally, many of Florida’s locally governed public colleges experienced enrollment declines before the pandemic that only grew steeper after its onset.

Also like their counterparts, these post-secondary schools, which, like state universities, are coordinated under the jurisdiction of the State Board of Education, have been exploring and adopting strategies to fill their seats.

Valencia College on Florida’s east coast, for example, began offering scholarships to students who failed remote classes they attended during the pandemic, allowing then to repeat the classes on campus as in-person instruction resumed.

Others started “summer bridge” programs to help new students feel more prepared when the fall term starts.

Programs that have gained the most attention are those that reach prospective students before they receive high school diplomas. Those include dual enrollment options that allow students to attend classes on college campuses or take courses from high school faculty members specially trained to teach them, as well as early college high school programs that allow students to earn college credits while completing their high school diplomas.

To facilitate the former, Florida lawmakers in 2021, after years of participation decline among private schools due to prohibitive costs, approved funding to cover tuition and fees for private school students who take dual enrollment classes. (Funding already had been in place for public school students through their school districts, and state law barred colleges from charging home school students who participated.)

The most recent example of the latter is St. Petersburg College in Florida’s Tampa Bay area, which recently announced the opening of its third collegiate high school. The new school will use $2 million in new state funding, and unlike the two existing collegiate high schools, will be open to freshmen.

The first collegiate high school under St. Petersburg College auspices opened as a public charter school of choice in 2004 on the St. Petersburg/Gibbs campus. A cavalcade of honors followed. Newsweek named it one of America’s Top High Schools in 2016, ranking it No. 2 in Florida and No. 55 in the nation. U.S. News & World Report named St. Petersburg Collegiate High School to its list of 2019 Best High Schools.

The new downtown St. Petersburg campus will allow students in grades 9-12 to simultaneously earn a high school diploma, two industry certifications and an associate in science degree. Like the other two collegiate high school campuses, there will be no cost to students for books, fees or tuition.

Starla Metz, St. Petersburg College’s vice president of collegiate high schools, said the college’s newest pre-collegiate program will infuse reading, writing, critical thinking, research and college readiness skills into its curriculum. Juniors and seniors will take part in the collegiate program, where they dual enroll in college classes.

Overall, the school will focus on preparing students for careers in science, technology, engineering and math, commonly referred to as STEM.

Metz recently told St. Pete Catalyst that as technology evolves, STEM education is “absolutely critical” to prepare students for high-paying jobs. Like its counterparts, the new campus in downtown St. Petersburg will offer associate degrees in computer information technology, data systems and business intelligence.

With some additional courses over the summer, graduating seniors can earn their associate in arts degree to continue their education at St. Petersburg College or another Florida college or university.

“We’re really excited because we think STEM is the future, and that’s where our students are going to have the opportunity to have economic mobility for themselves and their families," Metz said.

Research from the non-profit, non-partisan American Institutes for Research on the impact of early college programs showed a substantial positive impact not only on college enrollment but degree completion each year between the fourth year of high school and six years after expected high school graduation.

The study also found that early college students complete college degrees earlier and faster than those who did not participate.

While some of the nation’s most prestigious universities have celebrated banner years for applications, the pandemic has been hard for most post-secondary institutions. More than 1 million fewer students are enrolled in college now than before the pandemic began. According to data released in January by the National Student Clearinghouse, U.S. colleges and universities saw a drop of nearly 500,000 undergraduate students in the fall of 2021, continuing a historic decline that began the previous fall.

Compared with the fall of 2019, the last fall semester before the coronavirus pandemic, undergraduate enrollment fell a total of 6.6%, representing the largest two-year decrease in more than 50 years.

The nation's community colleges were hit even harder, with a 13% enrollment drop over the course of the pandemic. But the fall 2021 numbers showed that bachelor's degree-seeking students at four-year colleges made up about half of the decline among undergraduates.

Researchers found that many students who took a gap year during the pandemic weren’t returning. Speculation was that many were choosing to work as the economy rebounded and jobs became plentiful.

"The phenomenon of students sitting out of college seems to be more widespread. It's not just the community colleges anymore," said Doug Shapiro, who leads research at the National Student Clearinghouse and who spoke to NPR about the report.

"That could be the beginning of a whole generation of students rethinking the value of college itself. I think if that were the case, this is much more serious than just a temporary pandemic-related disruption."

For information about St. Petersburg College’s new STEM collegiate high school located in downtown St. Petersburg, as well as the college’s other two collegiate high school locations, click here.

Pasco County district officials hope to work with Pepin Academy, which serves students with unique abilities, in nearby Hillsborough County. The 21-year-old charter school is set to open its new technical education magnet high school in August.

Nationally, the war between charter and district schools continues to rage.

In Washington, D.C., the U.S. Department of Education has proposed new rules for start-up grants that charter advocates say make it virtually impossible for new charters to open. In Kentucky, Gov. Andy Beshear last week vetoed a bill that would establish permanent funding for charter schools five years after state lawmakers authorized charters but failed to create a funding plan.

Meanwhile, In Tallahassee, Leon County School Superintendent Rocky Hanna blamed education choice for his district’s financial problems and is seeking to block two new charters from opening.

Then there’s Pasco County.

Not only does peace reign in this bedroom community just north of Tampa, Florida, but district administrators are seeking to join hands and sing Kumbaya with local charter school leaders.

Their goal: To create formal partnerships to accommodate population growth that is happening at breakneck speed.

“The war between public and charter schools is over,” said deputy superintendent Ray Gadd, a veteran administrator and the architect of the plan. “Charter schools are here to stay, and we want to work with them, especially the local ones that we know well.”

U.S. Census figures show that Pasco’s population, estimated at 464,697 in 2010, grew to 561,891 in 2020. The county administrator compared the growth to the equivalent of “a good-sized city.”

The resulting housing boom is challenging the school district’s ability to provide seats to accommodate the influx of students. Charter schools face fewer regulations when opening and are eager to expand.

For Gadd, it’s a match made in heaven.

That’s why he and Superintendent Kurt Browning got the Pasco County School Board’s blessing to proceed with the plan late last year. Such a partnership would allow the district to get help educating new students in the Angeline development, a 6,200-acre site that is expected to house 30,000 new residents.

Within the area is a 775-acre parcel – larger than downtown Tampa – that will be home to a Moffitt Cancer Center research and corporate innovation district. The 128,000-square-foot corporate business park, slated for completion within the next five years, is expected to generate 430 full-time jobs.

Pasco administrators have invited Dayspring Academy, a charter school that has operated in Pasco for the past two decades, to consider building a K-5 school in the development with assistance that could include impact fees that the district collects from developers to accommodate growth, district capital funds, or bonding.

Under these agreements, the charter builds and manages the school, though a “step in” clause allows the district to operate the facility as a public school should something go wrong that results in charter school closure.

The elementary school would complement a school the district has planned in the area that will focus on science, technology, engineering, and math for students in grades 6 through 12.

John Legg, a former Florida state senator who co-founded Dayspring, said he would welcome any partnership opportunities. Dayspring has historically focused on lower-income communities on the county’s west side and has recently expanded, opening a new collegiate high school, with plans to open another school in a nearby low-income area.

“We’re really grateful,” said Legg, who serves on the governance board for Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog. “We’re now going into our 23rd year in Pasco and we’ve played nice in the sandbox with everybody.”

He said the permitting and inspection process is slow in this fast-growing county. In Pasco, an interlocal agreement with the county lets district officials handle permitting for charter schools that opt into an agreement to do so.

That speeds up the process for the charters, which otherwise would have to get back in a long line for a follow-up inspection with the county. The district arrangement can accommodate a quick turnaround. That’s good for charter schools, which unlike other businesses, can’t postpone opening.

“If we fail an inspection in one bathroom in the corner, we can’t not open the school,” Legg said, adding that the school has a waitlist of 400 students in the area near Angeline.

Pasco district officials also hope to work with Pepin Academy, a 21-year-old charter school based in adjacent Hillsborough County to open a campus near its new technical education magnet high school, which is set to open in August.

Pepin, which serves students with unique abilities, already operates a campus in the county for 400 students in kindergarten through 12th grade but sees potential to expand in a rapidly growing area on the other side of county.

“If they can help us get better, and we can help them, why not?” Pepin spokeswoman Natalie King told the Tampa Bay Times. “We want to be a great partner. What we do is unique, and it’s supplemental in terms of what the district is doing.”

Gadd said that corporate-owned charter schools have popped up in densely populated areas of the county, and while the district welcomes them, it prefers to reserve the partnerships for charters that are independent and homegrown.

“Those schools are great, but they don’t need our help,” he said.

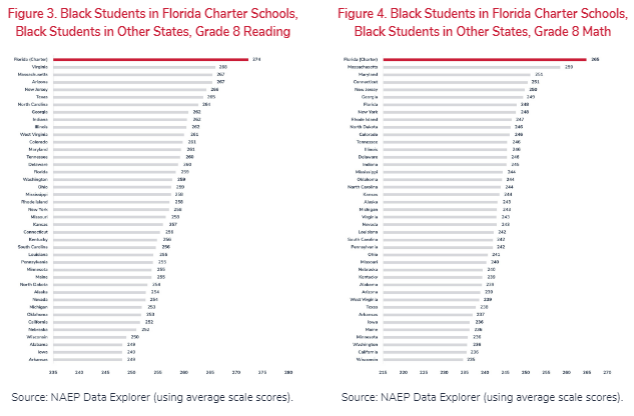

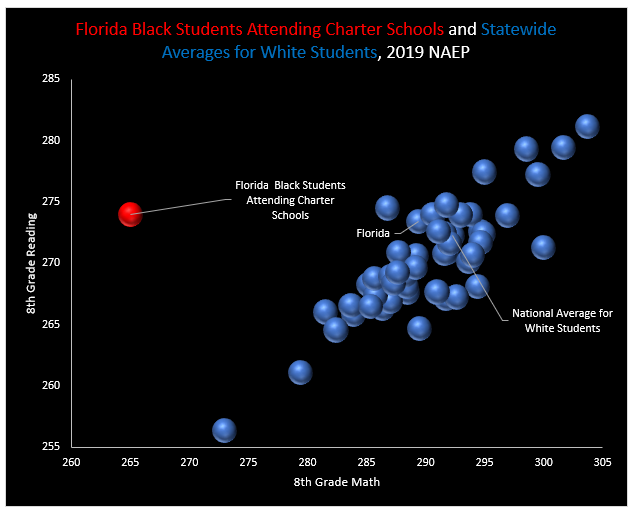

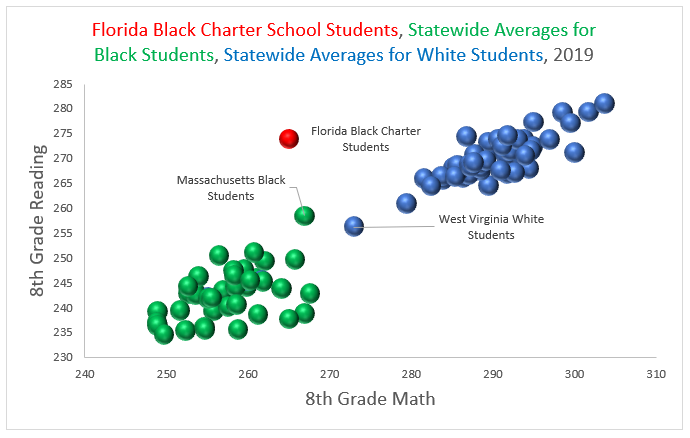

I read the new American Federation for Children/Step Up for Students study on choice for Black students in Florida, and found a bit of inspiration in the following charts:

I read the new American Federation for Children/Step Up for Students study on choice for Black students in Florida, and found a bit of inspiration in the following charts:

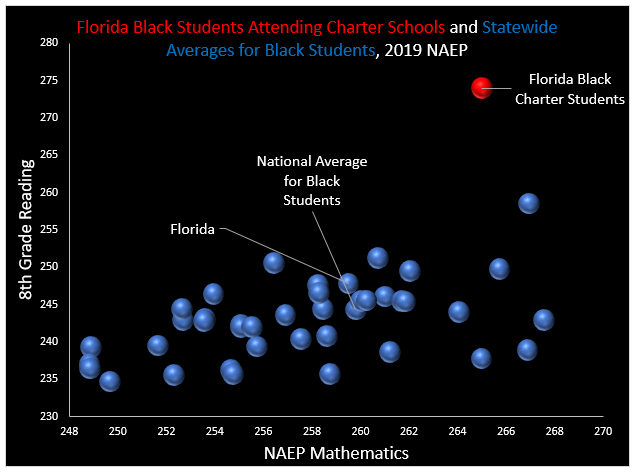

These charts compare the NAEP scores for Black students attending Florida charter schools to those of statewide averages for Black students. I asked myself, “Self, how would this look if we combined these two charts into one chart?”

These charts compare the NAEP scores for Black students attending Florida charter schools to those of statewide averages for Black students. I asked myself, “Self, how would this look if we combined these two charts into one chart?”

In the chart below, 10 points approximately equals an average grade level worth of work on these exams, so Florida charter students were looking good in 2019.

Next, I said to myself, “Self, what if we compared the scores of Florida Black charter school students to statewide averages for white students?”

Next, I said to myself, “Self, what if we compared the scores of Florida Black charter school students to statewide averages for white students?”

Here’s what that looks like:

So, a couple of things to note: Florida’s Black charter students had a level of reading achievement similar to white students nationally as well as in Florida. Second, a large achievement gap remains in math.

So, a couple of things to note: Florida’s Black charter students had a level of reading achievement similar to white students nationally as well as in Florida. Second, a large achievement gap remains in math.

So, put it all together and it looks like this:

We clearly have a great many miles to go. Some will crawl, others will walk. Some, like Florida, relatively speaking, have been running.

We clearly have a great many miles to go. Some will crawl, others will walk. Some, like Florida, relatively speaking, have been running.

As Dr. King said: Keep moving.

Somerset Academy, Florida's largest charter school network, operates schools throughout the state, including Somerset Academy K-5, 6-8 and 9-12 in Jefferson County.

Nearly five years after taking over operations of Jefferson County’s struggling school system, Somerset Academy, Inc. is preparing to return control to the local school board.

“I’m super proud of how far we’ve come,” said Cory Oliver, who has served as principal of the combined K-12 campus since two district schools were turned over to the South Florida based charter school network. “It’s a completely different school.”

Oliver, whose office sports a Superman theme, has a lot to feel good about.

The percentage of students receiving passing scores on state standardized tests, which once were in single digits, are now between 35 and 45% in most subjects. Disciplinary referrals are down by 80% since the start of the 2020-21 school year. The district, which earned D’s in the two years prior to Somerset’s arrival, has improved a letter grade.

The high school graduation rate rose by almost 20 percentage points this year, though state officials caution that may not be accurate as many students were not required to retake graduation tests due to the coronavirus pandemic. Meanwhile, enrollment, which was a little less than 700 in 2017 and represented only about half of all eligible students who lived in the district, has increased to about 779.

The improvements go beyond academics. Somerset installed a new kitchen and added a culinary arts program and built a recording studio. It renovated the gym and refurbished the weight room. Band members got new instruments and football players no longer had to share shoulder pads.

The JROTC program, impressive before Somerset took over, continues to be a shining star. Trophies hidden away in closets are now displayed in trophy cases. Classrooms got technology upgrades. Students got new uniforms.

“It’s like night and day. These kids have been in poverty and living without for so long,” Oliver said. “We want them to see what’s possible and feel like this is home and that they deserve to be here.”

Oliver’s philosophy was reflected in the school’s motto for 2019-20: “Whatever It Takes!” to Somerset officials, it took everything they had to improve what had been the lowest performing schools in the state.

“When we got here, the staff was exhausted and overwhelmed,” Oliver said. “The staff is still exhausted and overwhelmed, but they’re seeing results. They’re seeing what’s possible when they work as a team and know they are going to be supported.”

Residents of Jefferson County, a 637-square-mile area with a population of about 15,000, once were proud of their schools, which were a model for other districts, according to comments Jefferson County School Board member Shirley Washington made at a State Board of Education meeting in 2016.

“We used to be the flying Tigers,” Washington said, referring to the school’s Tiger mascot. “We had other schools come to our county and see what we were doing. We’re going to get it back there. There’s no doubt in my mind.”

But to state officials, the Jefferson County schools looked more like the crash-and-burn Tigers. Florida Department of Education officials came to visit and did not like what they saw.

More than half of the students at Jefferson Middle-High School had been held back two or more times. Just 7% of middle schoolers scored at grade level on 2016 state math assessment. To put that in perspective, 26% of students were performing at grade level in the state’s second-lowest performing district. Enrollment had dwindled for years as more families sent their students to private schools or district schools in neighboring counties. Finances also were a mess.

After rejecting the three turnaround plans that district officials submitted, the Board of Education took an historic vote to make Jefferson County schools the state’s first district run by a charter school provider. The solution mirrored education reform in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina decimated the schools.

Somerset Academy, Inc. won the bid to assume control.

Somerset staff arrived to discover complete disarray: crumbling buildings, graffiti-covered walls, old equipment stacked against classroom walls and no enforcement of discipline.

“It was way worse than we ever imagined,” said Todd German, chairman and treasure of Somerset’s board of directors. “These did not look like places anyone would want to come to learn or come to work.”

School board members pledged to cooperate with Somerset but later said they were “coerced” into accepting the arrangement. The superintendent at the time told WLRN Public Radio that the Department of Education “played in places they shouldn’t have.” Education Commissioner Pam Stewart countered, stating it was “very clear that the Department acted within their authority.”

The charter network fired about half the staff and recruited new teachers. Teacher salaries were raised to $43,800, compared to $36,160 teachers in neighboring Leon County earned. The network hired additional security officers at the schools, where fights had broken out almost daily. One brawl, which occurred just a few months after Somerset came on board, resulted in 15 arrests.

“It was like the wild West,” German recalled, while acknowledging the problems were caused by a small percentage of students. “Cory improved security and put in some zero tolerance policies.”

Oliver said staff from Somerset arrived to find a culture of apathy. Students were allowed to loiter in the halls or outside when they should have been in class.

After the takeover, he said, even the maintenance staff pitched in, alerting administrators when they saw anyone who didn’t belong on campus. Custodians engaged students who looked stressed to make sure they were okay.

“We were de-escalators, not enforcers,” said Oliver, who also hired mental health specialists and started a mentoring program for younger students.

Slowly, the culture began to change. Community members, including the Rev. Pedro McKelvin of Welaunee Missionary Baptist Church, began to support the new leadership. Before the takeover, he said, the district “was on the brink of collapse.”

Christian Steen, a senior, credited Oliver with boosting morale and observed that things had improved significantly.

“The students are more focused in class and now there’s not much skipping,” said Steen when he spoke before a House Education Committee three months after the takeover.

As they enter the last year of their contract, Somerset officials want to prepare to hand the district back to local officials. They already have begun working with a newly elected superintendent to meet that goal. Somerset has offered to let a new principal hired by the school district shadow Oliver before he leaves.

“I have a lot of feelings about leaving Jefferson,” said German, Somerset’s chairman. “I hope we can set (the schools) up to succeed.”

Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill

Editor’s note: This post is an edited version of a talk Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill delivered in October to the Florida Charter School Conference in Orlando.

Products and services in many industries are in the process of being unbundled. Thirty years ago, we had to buy albums to own our favorite songs. Now we can buy individual songs and bits of songs online.

Classified newspaper ads used to be a cash cow for daily newspapers. But no more. Craigslist’s unbundling of classified ads is a key reason daily newspapers are dying.

The demise of cable TV may be next as streaming services such as Netflix unbundle programing. Shopping malls are closing as Amazon unbundles retail shopping, and banks are responding to the unbundling of banking services by licensing unbundled banking applications in a new business model called “banking as a service.”

Now the process of unbundling public education services has begun. Thus far, this unbundling has included magnet schools, charter schools, dual enrollment, virtual schools, course choice, micro-schools, home schooling, workspace, and scholarships and vouchers to help families pay for private schools.

But the real game changer will be Education Scholarship Accounts (ESAs). ESAs are going to accelerate the unbundling of public education services.

ESAs are publicly-funded financial accounts that families use to purchase state-approved education products and services for their children. Instead of a school district spending a student’s public education dollars, through ESAs state government allows a student’s family to spend these dollars.

About 18,000 Florida students will have ESAs this school year through two programs -- the Gardiner Scholarship for students with special needs/unique abilities, and Reading Scholarship Accounts for struggling readers in district elementary schools. These students’ families will use their ESA funds to purchase products and services, such as public and private school courses, afterschool tutoring, physical and occupational therapy, speech therapy, education hardware and software, summative and formative assessments, curriculum material, and books. Over the last two years, Florida families have used ESA funds to purchase products and services from over 10,000 education providers.

The number of families using ESAs will probably increase in the future. In six years, Florida could have 200,000 families spending $1.5 billion annually through their ESAs. This much purchasing power in the hands of families presents opportunities and challenges for Florida’s charter schools.

There will be competition to serve these families. Charter school companies in other states are exploring coming to Florida with offerings beyond schools. Some are planning to open charter and private schools with robust afterschool and summer programs. Others are planning to sell onsite and online courses, and one is exploring partnering with ride-sharing services to help transport students to in-school, afterschool, and summer programs. Think “Uber for Kids.”

Home schooling is the fastest growing education choice option in the country. Charter schools could be selling this population access to classrooms, computer and science labs, afterschool and summer programs, and onsite and online courses.

With the possible exception of Miami-Dade, most Florida districts will be slow to offer services to ESA families. Florida charter schools could help fill this void.

Dayspring Academy charter school in Pasco County moved quickly to create an afterschool tutoring program after the Reading ESA became law. It is now one of Florida’s top providers of ESA-funded tutoring services. (Dayspring founder and chief financial officer John Legg is a board of directors member for Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

Other charters could follow the Dayspring example. Entrepreneurial Urban Leagues across Florida are also moving quickly to develop afterschool and summer reading programs for families with reading ESAs.

The unbundling of products and services inevitably leads to innovative ways to rebundle them. Spotify is a good example of a company facilitating rebundling in the music industry. Spotify empowers and enables music listeners to organize songs from diverse artists into customized playlists and share these lists with others. Spotify empowers customers to have a greater sense of ownership over their music since they now control how their “albums” are assembled. They also have access to the diverse playlists of millions of other music fans.

We need to replicate an appropriate version of the Spotify experience in public education. Educators need to be empowered and enabled to rebundle their services and products so that families can purchase highly effective customized instruction for each child with their ESA funds.

The unbundling and rebundling of education products and services is coming. Charter schools can help drive this train or follow the example of daily newspapers and get run over by it.

It’s their choice.

Charter schools and home schooling are experiencing major growth. Meanwhile, there were no significant differences between students in charter schools and traditional public schools in average reading and mathematics scores on national tests in 2017.

Those are two of the key findings in the U.S. Department of Education’s (USDOE) latest report, “School Choice in the United States,” which updates the national changing landscape for school choice with changes in enrollment data, academic performance updates, and parental satisfaction surveys. Nationally, charter public schools and district schools increased enrollment while private schools declined.

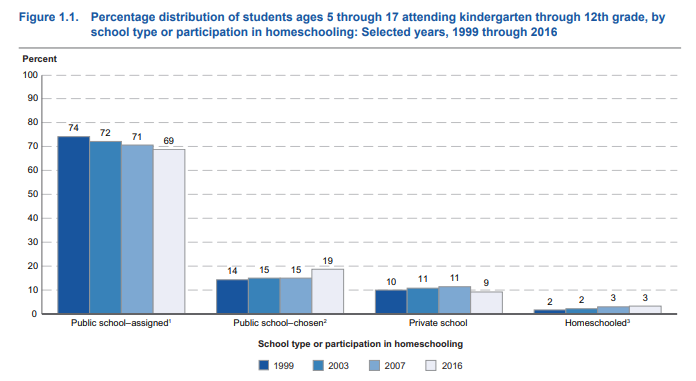

Overall, there were around 57.8 million K-12 students in the United States, up from 53.8 million in 1999. Based on figures from the USDOE, the market share of district schools fell from 87 percent of all students in 1999 to 81.8 percent of students by 2016.

From 1999 to 2016 the share of students attending their assigned neighborhood public schools dropped from 74 percent to 69 percent. Public school choice option, including charter schools, magnet schools and open enrollment programs, grew from 14 percent of the student body in 1999 to 19 percent. Charter schools alone grew a staggering 571 percent from 2000 to 2016, enrolling over 3 million students by 2016.

Private school options fell from 10 percent to 9 percent, while home education grew from 2 percent to 3 percent by 2016.

Unlike most of the nation, however, Florida has seen private school enrollment bounce back. In 2000, 348,000 students enrolled in nonpublic schools, comprising 12.5 percent of the total PK-12 student body. Thanks to the help of several private school programs, including the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, private schools in the Sunshine State continue to grow. In 2018-19, the latest data available, 380,000 students enrolled in nonpublic schools, though the market share has declined to 11.8 percent of Florida’s total PK-12 student population.

Catholic schools remain the top choice among private school parents, enrolling more than 2 million students in 2016, more than double any other denomination.

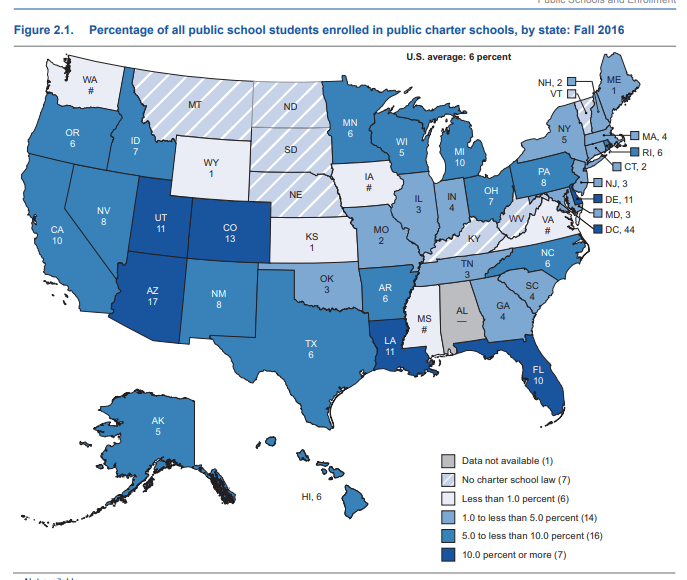

District schools enrolled 94 percent of all public school students, with charters enrolling the other 6 percent. District schools were more likely to enroll white students, and less likely to enroll black or Hispanic students, than charters. According to the USDOE, 57 percent of public schools were 50 percent or more white, while just 33 percent of charters were. Charters were more likely to be 50 percent or higher black or Hispanic, however.

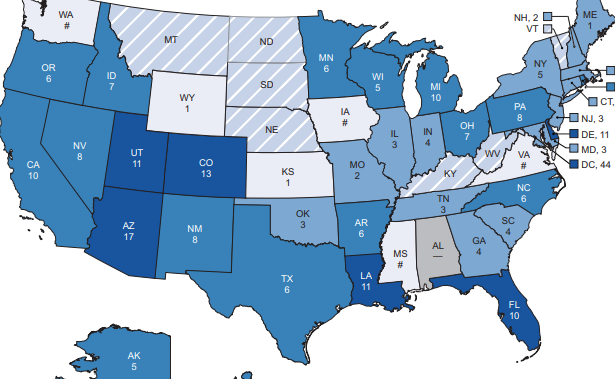

Enrollment in charter options varies greatly among states, though one important pattern emerges just in time for the Democratic presidential primaries: Important swing states Florida, Arizona and Michigan have large charter school populations.

Meanwhile, the USDOE reports “no measurable difference” between the average district students and charter school students on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) exams in reading in math in 2017.

Charter school students, including black, Hispanic and free and reduced-price lunch students, saw higher raw NAEP scores in fourth-grade reading than in traditional public schools, and were no different on eighth-grade reading. White, black and Hispanic students attending charters also saw higher raw scores on eighth-grade math, and were no different on fourth-grade math.

According to the report, 1.7 million students attended a home school setting in 2016. Home school students were more likely to live in a rural setting or small town than be urban or suburban. Homeschooling was also more common in the South and West than in the Northeast.

Home school parents had various reasons for choosing the option, according to the USDOE. About 34 percent of home education parents chose home schooling over public schools due to concerns about a school’s environment such as safety, drugs or negative peer pressure. Seventeen percent were dissatisfied with instruction, and 16 percent wanted to provide religious instruction.

Choice also played a significant role in parental satisfaction. Sixty percent of parents choosing a public school option were satisfied with the school, compared to 54 percent of parents with students at assigned public schools. Seventy-seven percent of parents enrolling children in private schools reported being satisfied with the school. A similar pattern emerges regarding satisfaction for academic standards, school discipline and regarding interaction between staff and parents.