By David Heroux and Ron Matus

In the blink of an eye, à la carte learning in Florida has become one of the fastest-growing education choice options in America.

This school year, 140,000 Florida students will participate in à la carte learning via state-supported education savings accounts, up from 8,465 five years ago. Their parents will spend more than $1 billion in ESA funds.

These families are at the forefront of epic change in public education. Completely outside of full-time schools, they’re assembling their own educational programming, mixing and matching from an ever-expanding menu of providers.

Nothing on this scale is happening anywhere else in America.

To give policymakers, philanthropists, and choice advocates a snapshot, we produced this new data brief. In broad strokes, it shows a more diverse and dynamic system where true customization is within reach for any family who wants it.

ESAs shift what’s possible from school choice to education choice. They give more families access not only to private schools, but tutors, therapists, curriculum, and other goods and services.

Adoption of these more flexible choice scholarships has been booming nationwide; 18 states now have them. But nowhere is their full potential more fully on display than in Florida.

Last year, 4,318 à la carte providers in Florida received ESA funding, more than double the year prior. Many of them are tutors and therapists, but a growing number offer more specialized and innovative services, as we highlighted in our first report on à la carte learning. Former public school teachers are also a driving force in creating them, just as they’ve been with microschools.

How far and fast à la carte learning will grow remains to be seen. For now, check out our brief to get a glimpse of what’s ahead.

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. – Four years ago, Phil and Cathy Watson were distressed and desperate. Their daughter Mikayla, then 12, was born with a rare genetic condition that led to physical and cognitive delays. With her school situation getting worse by the day, they needed options, now.

The Watsons were open to private schools. But they couldn’t find a single one near their home in metro D.C. that met Mikayla’s needs. They even looked in neighboring states. Nothing.

One day, though, Phil varied his keyword search slightly, and something new popped up:

A school for students with special needs that had low student-to-staff ratios, transition programs to help students live independently, even an equine therapy program.

The Watsons feared it was too good to be true. Even if it wasn’t, it was 700 miles away.

A destination for education

Florida has always been a magnet for transplants. It’s tough to beat sunshine, low taxes, and hundreds of miles of beach. But as Florida has cemented its reputation as the national leader in school choice, the ability to have exactly the school you want for your kids is making Florida a destination, too.

In South Florida, Jewish families are flocking from states like New York to a Jewish schools sector that has nearly doubled in 15 years. But they’re not alone. Families of students with special needs are making a beeline for specialized schools, too. The one the Watsons stumbled on has 24 students whose families moved from other states – about 10% of total enrollment.

The common denominator is the most diverse and dynamic private school sector in America, energized by 500,000 students using education choice scholarships.

According to the most recent federal data, the number of private schools in Maryland shrank by 7% between 2011-12 and 2021-22. In Florida, it grew by 40%.

“What Florida is offering is just mind blowing compared to Maryland,” Phil said. “If a story like this ran on the national news, people would be beating the door down.”

‘The kid who never spoke’

Phil and Cathy Watson have six children, all adopted. They range in age from 1 to 39. All have special challenges.

“God picked out the six kids we have,” said Cathy, who, like Phil, is the child of a pastor. “We feel very strongly that we were called to do what we do. Our heart says we have love to give and knowledge to share. These kids need that, so it’s a match.”

Mikayla is their fourth child. She was born with hereditary spastic paraplegia, a condition that causes progressive damage to the nervous system.

She didn’t begin walking until she was 18 months old. Even then, her gait continued to be heavy-footed, and she was prone to falling. Her speech was also, in Phil’s description, “mushy,” and until she was 12, she didn’t talk much.

In many ways, Mikayla is a typical teen. She loves steak and sushi and Fuego Takis. Her favorite books are “The Baby-Sitters Club” series, and her favorite movies include “Beauty and the Beast” and “Beverly Hills Chihuahua.” Many of her former classmates, though, probably had no idea.

In school, Mikayla was “the kid who never spoke.”

Checking a box

As Mikayla got older, she and her parents grew increasingly frustrated with what was happening in the classroom. “She was being pushed aside,” Phil said.

Teachers would tell her to read in a corner. Between the physical pain from her condition and the emotional turmoil of being isolated, she was crushed. Sometimes, Phil said, she’d come home and “unleash this fury on my wife and I.”

The pandemic made things worse. In sixth grade, Mikayla was online with 65 other students. Then, three days before the start of seventh grade, the district said it no longer had the resources to support her with extra staff. Instead, she could be mainstreamed without the supports; enroll in a private school; or do a “hospital homebound” program.

The Watsons chose the latter. Three days a week, a district employee sat with Mikayla, going over worksheets that Phil said were “way over her head.”

“All it was,” he said, “was checking a box.”

Just in the nick of time, the school search turned up a hit.

Florida, the land of sunshine and learning options

What surfaced was the North Florida School of Special Education.

“From just the pictures, I’m thinking, ‘This looks legit,’ “ Phil said. “Both of us are like, ‘Wow.’ “

When the Watsons called NFSSE, as it’s called for short, an administrator answered every question in detail. This was not the experience they had with some of the other private schools they called.

At the time, Phil owned a home building company, and Cathy worked for a counseling ministry. They lived comfortably. But they were also paying tuition for another daughter in college.

Thankfully, the administrator told them Florida had school choice scholarships. For students with special needs, they provided $10,000 or more a year.

The Watsons couldn’t believe it. They were familiar with the concept of school choice but didn’t know the details. Maryland does not have a comparable program.

The administrator also told them NFSSE had a wait list. But the Watsons had heard enough.

A fortuitous phone call

A few weeks later, they were touring the school.

The facilities were stellar. Even better, the administrator leading their tour knew the name of every student they passed in the hallways. “We were blown away,” Phil said. “They truly care. “

At some point, the staff ushered Mikayla into a classroom. As her parents watched from behind one-way glass, another student greeted Mikayla with a flower made of LEGO bricks.

For years, Mikayla had been withdrawn around other students. Not here. The shift was immediate. She and the other students were using tablets to play an interactive academic game, and “you could see her turn and laugh with the kids next to her,” Phil said.

Minutes later, he and Cathy were in the administrator’s office, “bawling our eyes out.”

“We said, ‘We’re all in. We have to be here. We’ll be here next week if that’s what we have to do.’”

Days later, the Watsons were at Disney World when NFSSE called. Unexpectedly, the family of a longtime student was moving. The school had an opening.

New friends, improved skills and boosted confidence

Even without the choice scholarship, the Watsons would have moved. At the same time, the scholarship was invaluable. The cost was not sustainable in the long run, Phil said, especially because he had to re-start his business.

The Watsons rented a long-term Airbnb and then an apartment before buying a house in Jacksonville. They uprooted themselves completely from Maryland, including selling their dream home.

“That was hard,” Cathy said. “You’re leaving everything you love.”

Mikayla’s turnaround, though, has made it all worthwhile.

Mikayla was reading at a first-grade level when she arrived at NFSSE; now she’s at a seventh-grade level. She loves the new graphic design class. She won an award for completing 1,000 math problems. “When she got here, she couldn’t add two plus two,” Phil said.

Her verbal skills have blossomed. She eventually told her parents something she didn’t have the ability to tell them before: In her prior school, she didn’t talk because other students laughed at her.

At NFSSE, the “kid who never spoke” speaks quite a bit.

One day, she served as “teacher for the day” in her personal economics class, delivering a lesson on how to make change.

Mikayla is kind and quick to smile. She is surrounded by friends and admirers. “Mikayla is my best friend,” said a chatty girl with pigtails who waited by her side in the hallway.

One boy held the door for Mikayla as she headed to her next class. A second hung her backpack on the back of her wheelchair. A third walked her to P.E.

Mikayla’s confidence is growing outside of school, too.

In the past, she wouldn’t say hi or order in a restaurant. But at Walmart the other day, Phil needed a card for a friend’s retirement, so Mikayla went to find a clerk. She came back and told him, “Aisle 9.”

Mikayla has a bank account and a debit card. She tracks the money she earns from chores. She routinely uses the notes app on her phone to mitigate challenges with short-term memory.

NFSSE, Cathy said, is constantly reinforcing skills and strategies to foster independence. It “pushes for potential,” just like the families do.

Mikayla “sees that potential now; she’s excited now,” she said.

Before NFSSE, the Watsons didn’t think Mikayla could live independently. Now they do.

The school and the scholarship, Phil said, have “given Mikayla an opportunity for her life that we didn’t know existed.”

He credited the state of Florida, too, for creating an education system where more schools like NFSSE can thrive.

If only every state did that.

SAFETY HARBOR, Fla. – Edelweiss Szymanski turns 10 on a Friday in December. She will celebrate the milestone by running a 5-kilometer race in Daytona Beach. The next day, she’s scheduled to compete in a triathlon.

No pizza party. No theme park.

How many 10-year-olds want to run three miles on their birthday, then swim, bike, and run some more the day after?

“This one does,” Lacey Szymanski said, pointing to her daughter with both index fingers.

Meet Edelweiss, a young triathlete on the rise who’s as tough as the flower she’s named after. Meet her brother, Spartacus, too, 14 months younger and just as tenacious.

The SkiSibs, as they are known throughout Florida’s triathlon community.

Their bedrooms are filled with trophies, medals, and plaques – the spoils of reaching the podiums (finishing in the top three) at triathlons, road and bicycle races. The garage of their Safety Harbor home is packed with bicycles.

“We are an active family,” Lacey said.

Lacey and her husband, Jacek, have participated in triathlon relays.

Some mornings, Jacek and the kids can be found riding the bike trails around Pinellas County, waking as early as 3 a.m. so Jacek can get in a long ride before heading to his job as a sergeant with the Pinellas County Sheriff's Office.

If they time it right, and they usually do, the trio will stop along the overlook on the Courtney Campbell Causeway and snack on peanut butter and jelly sandwiches while they watch the sun rise over Tampa Bay.

“We really like watching the sunrise,” Edelweiss said.

She and Spartacus receive Florida education choice scholarships for students with unique abilities managed by Step Up For Students. Edelweiss is dyslexic. Spartacus has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). They are home educated by Lacey, who taught in a private school for 10 years before the family adopted this educational format.

Edelweiss benefits from one-on-one instruction with her mom, while Spartacus is not required to sit at a desk and complete his assignments, something that was an issue when he attended a brick-and-mortar school.

“The scholarship has been a game-changer. It’s awesome that Florida offers this,” Lacey said. “I have my doctorate in education, so I'm really happy that I'm able to help them in the ways that I can and create a curriculum that is specialized to their individual needs, as well.”

The scholarship covers Spartacus’s occupational therapy, as well as art class and piano lessons for Edelweiss. And learning at home allows for flexible schedules. It’s not unusual for Spartacus, an early riser, to complete his math assignments before the sun is up.

The family home borders a wetland, which is ideal for interactive science lessons. It also provided the sticks the kids used to carve their own forks, and the twigs Edelweiss used to create a bird’s nest.

“Her art style isn't cut and dry, like paint a picture of this penguin. It's more abstract,” Lacey said. “That’s the way her brain works. Music, art, and athletics are a lot easier for her. When dyslexia held her back from other things, she kind of poured herself into those things.”

Lacey was pregnant with her daughter, and she and Jacek had yet to settle on a name when she came across a music box she bought during a trip to Germany. It played the song “Edelweiss” from the movie “The Sound of Music.” An edelweiss is a stout flower that grows in the rugged high-altitude terrain of the Alps and the Carpathian mountain ranges in Europe and blooms in the winter.

“I thought, ‘That’s what I want to name my daughter,’” Lacey said.

She and her husband believe that people can become the personification of their names. That holds true with Edelweiss.

“She is very hearty, and it aligns with being a triathlete. She can endure a lot and has a high tolerance for the sport,” Lacey said. “And at the same time, it’s a very beautiful flower. It doesn't look like your normal flower. It's very different and unique, which is what she is.”

And Spartacus? Well, he was making a fist in his first ultrasound.

Jacek said he looked like Spartacus, the ex-slave who became a gladiator and led a rebellion against the Roman Republic in 71 BC.

“He said his name is going to be Spartacus, and I said, ‘Yeah, right. There's no way I would name my son Spartacus.’ And here we are,” Lacey said.

“We do get odd looks when we call his name at a triathlon,” Jacek said. “I’m not saying it’s like yelling ‘Fire!’ in a crowd, but almost.”

You will often find Edelweiss on top of the podium on race day. (Photo courtesy of the Szymanski family)

Edelweiss competed in her first triathlon when she was 5. The family belonged to a local YMCA, and Lacey saw a post about the race on the morning of the event. So, she woke Edelweiss and asked her if she wanted to give it a try. Edelweiss said yes.

“It gave me something to do,” she said.

The race consisted of one lap in the 25-meter pool, a half-mile bike ride, and a quarter-mile run. Competing on a bike that had pom-poms and a basket on the handlebars, Edelweiss won her age group.

She had one question for her mom when she finished.

“When can we do this again?”

The answer? As often as possible.

She and Spartacus have moved up to sprint triathlons – 400-yard swim, 8.1-mile bike ride, and a 5K run.

The hardest leg for Edelweiss is the run. The best part, she said, is crossing the finish line.

“Because I don’t have to run anymore,” she said.

She’s been known to finish a race in her socks. Once, when she developed blisters and tossed her shoes halfway through the race, and another time when she was having trouble getting them on during the transition from the bike to the run and didn’t want to waste more time.

Jacek was born in Poland and immigrated to the United States at 19. He was an avid cycler in his native country and passed that love on to his children.

Edelweiss and Spartacus also compete in long-distance cycling races, where they are often the top finishers in their 7-11 age group.

“They goof around when they’re going for a ride with dad,” Jacek said. “But something switches when they are in the competitive world. They put on their game face.”

Before being immersed in the world of triathlons, Edelweiss was all about her ballet lessons.

“She was very into ballet, but now she doesn’t want to go back,” Lacey said. “It’s not the same adrenaline rush.”

Their weekends are loaded with triathlons across the state and cycling races as far north as Virginia. Lacey keeps track of the schedule.

“It’s our lifestyle now,” Lacey said. “We’re always in the water or on bikes, doing something like that. Edelweiss doesn’t feel like she’s actually competing. She’s doing what she loves. Spartacus is a ball of fire, too. Both of them together just constantly amazes me about what they're capable of and the grit that they have to compete.”

Caleb Prewitt continued to shatter the perception of what someone with Down syndrome can’t do when he conquered the 26.2-mile course at the Bank of America Chicago Marathon on Oct. 12.

Caleb, 18, became the youngest person with Down syndrome to earn an Abbott Star for running one of the original six World Major Marathons.

The Jacksonville native, who receives a Florida education choice scholarship for students with unique abilities managed by Step Up For Students, is also recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as the youngest person with II2 (Intellectual Impairment, including those with Down syndrome) to run a half-marathon (13.1 miles). He did that when he was 16.

David, Caleb, and Karen pose near the finish line of the Bank of America Chicago Marathon. Photo courtesy of the Prewitt family

Since 2020, when he began running as a means of getting exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic, Caleb has completed 47 triathlons (swim, bike, run), five half-marathons, and now one full marathon.

(Read about Caleb’s story here.)

The marathon was his most daunting endeavor, requiring months of training. The race took its toll – he experienced leg cramps after 20 miles. Undeterred, he pressed on and continued to cheer those who lined the course and were cheering for him.

“That went on for miles and miles, and I couldn't stop him,” Karen said. “I wanted to save his energy, and he just wanted to do it. I said, ‘You know what? This is his race. He can do what he wants.’”

Those in the Florida running community who have come to know Caleb during the last five years, and the faculty and staff at the North Florida School of Special Education, which he has attended since he was 5 with the help of his scholarship, wouldn’t have expected anything less.

He is known around school as “Mr. Mayor” for his always sunny disposition, and he is a star on social media with more than 31,000 followers on Facebook and more than 45,000 on Instagram to his Caleb’s Crew pages.

Running the marathon for the National Down Syndrome Society, Caleb raised more than $2,000 for the charity. There were 40 teammates from the National Down Syndrome Society team cheering him on at various points along the course.

Caleb’s dad, David, greeted him at the finish line with a long hug and a kiss.

“So proud of you,” David told his son.

Caleb was one of 17 charity runners in the event, which meant he was featured around Chicago in ads for the marathon, and his story appeared on the race’s website.

The 17 and their families met at a reception the day before the race.

“Their stories were all great. You know, everybody's story is great,” Karen said. “It's just that I think ours is great, too.”

That prerace publicity and the fact that he and Karen wore blue shirts with “Caleb’s Crew” on the front made him stand out somewhat in the field of 54,000 competitors.

“The crowd was amazing,” Karen said. “The whole way there was support and people cheering for Caleb. Everywhere we went, they knew his name, so that was a thrill.

“It was an awesome experience. What a wonderful day.”

Jordan Glen School started in 1974 on 20 acres of woods in the small town of Archer near Gainesville. Owner Jeff Davis, a former public school teacher, moved to Florida from Michigan to start a school that allowed students more freedom. Today it continues to thrive, thanks in part to education choice scholarships. Photo by Ron Matus

ARCHER, Fla. – Archer is a crossroads community of 1,100 people 15 minutes from the college town of Gainesville, but far enough away to have its own quirky identity. It’s surrounded by live oak-studded ranch land but calling it a “farm town” doesn’t ring right. When railroads ruled the Earth, Archer was a whistle stop on the first line connecting the Atlantic to the Gulf. In the late 1800s, T. Gilbert Pearson, co-founder of the National Audubon Society, roamed the woods here as a kid, skipping school to hunt for bird eggs. A century later, rock ‘n roll icon Bo Diddley spent his golden years on the outskirts.

So, let’s just say Archer is a neat little town. And maybe it’s fitting that for half a century, it has been home to a neat little private school that doesn’t fit into any boxes, either.

Jordan Glen School got its start in 1974, when former public school teacher Jeff Davis moved down from Michigan. In the late 1960s, Davis became disillusioned with teaching in traditional schools. In his view, students were respected too little and labeled too much.

“Back in the day, I would have been labeled ADHD. I hated school,” he said. “I never met a teacher that took a personal interest in me.”

As a teacher, he saw a system that was “too constricting.”

“There was just a general distrust of children, like they were going to do something bad,” he said. Education “doesn’t have to be rammed down your throat.”

Davis migrated to what was, more or less, a “free school,” with 50 students on a farm near Detroit. Today we’d call it a microschool.

In the 1960s, hundreds of these DIY schools emerged across America, propelled by an upbeat vision of education freedom inspired by the counterculture. Davis said the Upland Hills Farm School was a free school, more or less, because while its teachers were “long-haired” and “hippie-ish,” the school had more structure and rigor than free school stereotypes would suggest.

Davis thought the Gainesville area would be a good place to start a similar school. It had a critical mass of like-minded folks. So, in 1973, he and his family bought 20 acres of woods off a dirt road in Archer. Not long afterward, they invited a little school called Lotus Land School, then operating out of a community center in Gainesville, to move to their patch in the country. Today we’d call Lotus Land a microschool, too.

It was also, more or less, a free school. Davis described the teachers and families as “love children” and “free spirits,” but in many ways, their approach to teaching and learning was mainstream. A decade later, he changed the name. “I thought people would think it was a hippie dippy school, and I knew it was more than that,” he said.

Lotus Land became Jordan Glen. The school was named after the River Jordan, after some parents and teachers suggested it, and after basketball legend Michael Jordan, because Davis was a fan.

Fast forward a few more decades, and Jordan Glen School is thriving more than ever.

It now serves more than 100 students in grades PreK-8, some of whom are the second generation to attend. Nearly all use Florida’s education choice scholarships. Actor Joaquin Phoenix is among Jordan Glen’s alums. So is CNN reporter and anchor Sara Sidner.

Jordan Glen is yet more proof that education freedom offers something for everyone and that its roots are deep and diverse. Ultimately, the expansion of learning options gives more people from all walks of life more opportunity to educate their children in line with their visions and values.

“There is something about joy and happiness that makes people uneasy and a bit insecure,” Davis wrote in a 2005 column for the local newspaper, entitled “Joyful Learning is the Most Valuable Kind.” “If children are enjoying school so much, they must not be doing enough ‘work’ there.”

“Children at our school,” he wrote, “love life.”

A peacock, one of two dozen that roam the Jordan Glen School campus, watches students at play. Photo by Ron Matus

The Jordan Glen campus includes a handful of modest buildings. It’s still graced by a dirt road and towering trees. It’s also home to two dozen, free-roaming peacocks. They’re the descendants of a pair Davis bought in 1975 because they were beautiful and would eat a lot of bugs.

Given that backdrop, it’s not surprising that many families describe Jordan Glen as “magical.”

Alexis Hamlin-Vogler prefers “whimsical.” She and her husband decided to enroll their children, Atticus, 14, and Ellie, 8, in the wake of the pandemic.

“They’re definitely outside a lot,” she said of the students. “They’re climbing trees. They’re picking oranges.” When it rained the other day, her daughter and some of the other students, already outside for a sports class, got a green light to play in it and get muddy.

Another parent, Ilia Morrows, called Jordan Glen a “little unicorn of a school.”

Like Hamlin-Vogler, Morrows enrolled her kids, 11-year-old twins Breck and Lucas, following the Covid-connected school closures. She thought they’d stay a year, then return to public school. But after a year, they didn’t want to go back. “They had a taste of freedom,” she said.

For many parents, Jordan Glen hits a sweet spot between traditional and alternative.

On the traditional side, Jordan Glen students are immersed in core academics. They take tests, including standardized tests. They get grades and report cards. They play sports like soccer and tennis, and they’re good enough at the latter to win the county’s middle school championship. Many of them move on to the area’s top academic high schools.

But Jordan Glen also does a lot differently.

Students spend a lot of time outdoors at Jordan Glen School. Activities include archery, gardening and sports. Photo by Ron Matus

The students are grouped into multi-age and multi-grade classrooms. They choose from an ever-changing menu of electives. Many of those classes are taught by teachers, but some are taught by parents (like archery, gardening, and fishing), and some by the students themselves (like soccer, dance, and book club). The youngest students also do a “forest school” class once a week.

The school also emphasizes character education.

The older students serve as mentors for the younger students. They’re taught peer mediation so they can settle disputes. Every afternoon, they clean the school, working as crew leaders with teams of younger students. Their “Senior Class Guide” stresses nothing is more important than “caring about others.”

“The way the older kids take care of the younger kids, it’s very noticeable. They are genuinely caring,” Morrows said. At Jordan Glen, “they teach community. They teach being a good human.”

“My favorite thing is that most kids really get a good sense of self and self-confidence at this school,” Hamlin-Vogler said. “Some people say, ‘Oh, that’s the hippie school.’ But the students have a lot of expectations and personal accountability put on them.”

Hamlin-Vogler said without the education choice scholarships, she and her husband wouldn’t be able to afford the school. Hamlin-Vogler is a hairdresser. Her husband is a music producer. Before Florida made every student eligible for scholarships in 2023, they missed the income eligibility threshold by $1,000. Her parents were able to assist with tuition in the short term, but that would not have been sustainable.

Her family harbors no animus toward public schools. Atticus attended them prior to Jordan Glen, and he’s likely to be at a public high school next fall. Ellie, meanwhile, thinks she might want to try the neighborhood school even though she loves Jordan Glen in every way, and Hamlin-Vogler said that would be fine.

After Ellie described how much fun she had playing in the rain, though, Hamlin-Vogler had to remind her, “You might not get to do that at another school.”

The future of education is happening now. In Florida. And public school districts are pushing into new frontiers by making it possible for all students, including those on education choice scholarships, to access the best they have to offer on a part-time basis.

That was the message Keith Jacobs, director of provider development at Step Up For Students, delivered on Excel in Education’s “Policy Changes Lives” podcast A former public school teacher and administrator, Jacobs has spent the past year helping school districts expand learning options for students who receive funding through education savings accounts. These accounts allow parents to use funds for tuition, curriculum, therapies, and other pre-approved educational expenses. That includes services by approved district and charter schools.

“So, what makes Florida so unique is that we have done something that five, 10, even, you know, further down the line, 20 years ago, you would have never thought would have happened,” Jacobs said during a discussion with podcast host Ben DeGrow.

Jacobs explained how the process works:

“I’m a home education student and I want to be an engineer, and the high school up the street has a remarkable engineering professor. I can contract with the school district and pay out of my education savings account for that engineering course at that school.

“It’s something that was in theory for so long, but now it’s in practice here in Florida.”

It is also becoming more widespread in an environment supercharged by the passage of House Bill 1 in 2023, which made all K-12 students in Florida eligible for education choice scholarships regardless of family income. According to Jacobs, more than 50% of the state’s 67 school districts, including Miami-Dade, Orange, Hillsborough and Duval, are either already approved or have applied to be contracted providers.

That’s a welcome addition in Florida, where more than 500,000 students are using state K-12 scholarship programs and 51% of all students are using some form of choice.

Jacobs said district leaders’ questions have centered on the logistics of participating, such as how the funding process works, how to document attendance and handle grades.

Once the basics are established, Jacobs wants to help districts find ways to remove barriers to part-time students’ participation. Those could include offering courses outside of the traditional school day or setting up classes that serve only those students.

Jacobs said he expects demand for public school services to grow as Florida families look for more ways to customize their children’s education. That will lead to more opportunities for public schools to benefit and change the narrative that education is an adversarial, zero-sum game to one where everyone wins.

“So, basically, the money is following the child and not funding a specific system. So, when you shift that narrative from ‘you're losing public school kids’ to ‘families are empowered to use their money for public school services,’ it really shifts that narrative on what's happening here, specifically in Florida.”

Jacobs expects other states to emulate Florida as their own programs and the newly passed federal tax credit program give families more money to spend on customized learning. He foresees greater freedom for teachers to become entrepreneurs and districts to become even more innovative.

“There is a nationwide appetite for education choice and families right now…We have over 18 states who have adopted some form of education savings accounts in their state. So, the message to states outside of Florida is to listen to what the demands of families are.”

When I think about the state of public education in Florida, I recall a song from “The Wiz,” the 1978 film reimagining of “The Wizard of Oz,” where Diana Ross sang, “Can’t you feel a brand new day?”

It’s a brand new day in our state’s educational history. Parents are in the driver’s seat deciding where and how their children are educated, and because the money follows the student, every school and educational institution must compete for the opportunity to serve them.

Public schools are rising to meet that challenge.

For the past year, helping them has been my full-time job.

Today, 27 of Florida’s 67 school districts have contracted with Step Up For Students to provide classes and services to scholarship students, and another 10 have applied to do so.

That’s up from a single school district and one lone charter school this time a year ago.

This represents a seismic shift in public education.

For decades, a student’s ZIP code determined which district school he or she attended, limiting options for most families. For decades, Florida slowly chipped away at those boundaries, giving families options beyond their assigned schools.

Then, in 2023, House Bill 1 supercharged the transformation. That legislation made every K-12 student in Florida eligible for a scholarship. It gave parents more flexibility in how they can use their child’s scholarship. It also created the Personalized Education Program (PEP), designed specifically for students not enrolled in school full time.

This year, more than 80,000 PEP students are joining approximately 39,000 Unique Abilities students who are registered homeschoolers. That means nearly 120,000 scholarship students whose families are fully mixing and matching their education.

Families are sending the clear message that they want choices, flexibility, and an education that reflects the unique needs and interests of their children.

Districts have heard that message.

Parents may not want a full-time program at their neighborhood school, but they still want access to the districts’ diverse menu of resources, including AP classes, robotics labs, career education courses, and state assessments. Families can pay for those services directly with their scholarship funds, giving districts a new revenue stream while ensuring students get exactly what they need.

In my conversations with district leaders across the state, they see demand for more flexible options in their communities, and they’re figuring out how to meet it.

For instance, take a family whose child is enthusiastic about robotics. In the past, their choices would have been all-or-nothing. If they chose to use a scholarship, they would gain the ability to customize their child’s education but lose access to the popular robotics course at their local public school. Now, that family can enroll their child in a district robotics course, pay for it with their scholarship, and give their child firsthand technology experience to round out the tutoring, curriculum, online courses and other educational services the family uses their scholarship to access.

Families can log in to their account in Step Up’s EMA system, find providers under marketplace and select their local school district offerings under “contracted public school services.” School districts will get a notification when a scholarship student signs up for one of their classes. From large, urban districts like Miami-Dade to small, rural ones like Lafayette, superintendents are excited to see scholarship students walk through their doors to engage in the “cool stuff” public schools can offer. Whether it’s dual enrollment, performing arts, or career and technical education, districts are learning that when they open their arms to families with choice, those families respond with enthusiasm.

Parents are no longer passive consumers of whatever system they happen to live in. They are empowered, informed, and determined to customize their child’s learning journey.

This is the promise of a brand new day in Florida education. For too long, choice has been framed as a zero-sum game where if a student left the public system, or never even attended in the first place, the district lost. That us-versus-them mentality is quickly going the way of the Wicked Witch of the West. What we are witnessing now is something far more hopeful: a recognition that districts and families can be partners, not adversaries, in building customized learning pathways.

The future of education in Florida is not about one system defeating another. It is about ensuring families have access to as many options as needed, regardless of who delivers them.

As Diana Ross once sang, “Hello world! It’s like a different way of living now.” It has my heart singing so joyfully.

If education freedom were a hockey game, Florida just scored a Texas hat trick.

For the fourth consecutive year, Florida was ranked the No. 1 state for education freedom for K-12 students and families in The Heritage Foundation’s annual Education Freedom Report Card. The 2025 Heritage rankings come after a landmark year of state legislative sessions that delivered wins for students and families.

Florida leaders credited the state’s ranking to policies that give parents control over their children’s education dollars, offering a plethora of choices, including a la carte courses provided by school districts and charter schools.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signs HB 1, which offered families universal eligibility to Florida education choice scholarship programs.

“In Florida, we are committed to ensuring parents have the power to make the education decisions that are best for their child,” said Gov. Ron DeSantis, who in 2023 signed legislation that offered universal eligibility for K-12 state education choice scholarship programs that allow families to direct their dollars toward the best options for their children. “Florida offers a robust array of educational choices, which has solidified our state as a national leader in education freedom, parental power, and overall K-12 education.”

Commissioner of Education Anastasios Kamoutsas said earning the top ranking for four years affirms the state’s long-term commitment to families.

“Under Governor DeSantis’ leadership, Florida will continue honoring parents’ right to choose the best educational option for their child’s individualized needs. I am proud that Florida offers so many educational options that parents can have confidence in.”

Since the Education Freedom Report Card began in 2022, Florida has earned the top ranking every year. The report card uses five categories: school choice, transparency, regulatory freedom, civic education, and spending to rank states.

In addition to Florida receiving the overall top spot for Education Freedom, it also earned high rankings in the following categories:

Earlier this year, the Sunshine State also earned national recognition for putting dollars behind its policies. In January, the national advocacy group EdChoice put Florida first on its list of each state’s spending on education choice programs proportional to total education spending.

According to the EdChoice report, Florida became the first state to spend more than 10% of its combined private choice and public-school expenditures on its choice programs, rising from an 8% spending share in 2024.

According to the EdChoice report, Florida became the first state to spend more than 10% of its combined private choice and public-school expenditures on its choice programs, rising from an 8% spending share in 2024.

Florida also reached a historic milestone when, for the first time, more than half of all K-12 students were enrolled in an educational choice option. During the 2023–24 school year, 1,794,697 students, out of the state’s approximately 3.5 million K-12 population, used a learning option other than their assigned district school.

This is what home education looks like to Vivian McCoy:

Feeding horses in the morning. Mucking stalls, too. Doing the same in the late afternoon, plus whatever else needs to be done at the horse farm where she works part time.

In between, Vivian, who is in the ninth grade, and her sister, Genevieve, second grade, complete their schoolwork on the 15-acre farm where they live with their mom, AnnaMarie, in the Florida Panhandle community of DeFuniak Springs

“I feel I have way more free time to do the things I enjoy,” Vivian said, when asked about the benefits of home education.

That free time includes caring for her own two horses – Blue, a quarter Mustang mix, and Froggy, a Tennessee Walker – and tending to the other animals that live on what AnnaMarie calls a “teaching farm.”

Vivian and Froggy get ready to participate in the Fourth of July parade. (Photo courtesy of AnnaMarie McCoy)

Genevieve looks after the chickens and works in the 2,000-square-foot garden.

There are the core courses, for sure, but there is plenty of hands-on learning for the McCoy sisters in the only educational setting they have known.

Florida education choice scholarships help make it affordable for AnnaMarie, a single mom who works from home part-time as a dietitian consultant.

Genevieve receives the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA). Vivian receives the Personalized Education Program (PEP) scholarship available through the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program. Both scholarships are managed by Step Up For Students.

Like FES-UA, PEP is an education savings account (ESA) that gives parents the flexibility to customize their children’s learning to meet their needs. The scholarship, enacted by the Florida Legislature before the 2023-24 school year, has been a financial boon to AnnaMarie.

Until then, she paid out of pocket for the curriculum and supplies needed for Vivian’s home education.

“Pre-scholarship, it was a real struggle meeting all of her goals and being able to present her with things that were going to enhance her interests and her education,” AnnaMarie said. “Although we did it and we got through it, having the scholarship opens up an entire new world for us.

“I can use that money to really enhance what their interests are and what their weaknesses are, or their strengths.”

Like most students who are home educated, Vivian’s and Genevieve’s learning has evolved.

“I’ve gotten a lot more experience over the years to see what works for us,” AnnaMarie said. “These are two very different children, very different students, with very different interests and learning abilities. So, before the scholarship was an option, I definitely did things that were very budget-friendly and utilized anything that was a possible benefit to us that was low-cost, and I still do.”

Vivian is interested in agricultural science and animal husbandry. Hence, Blue and Froggy and her job at the horse farm.

“She's also very artistic,” AnnaMarie said. “She's super, super creative and super artistic.”

Genevieve displays the vegetables she grew in the family's 2000-square-foot garden. (Photo courtesy of AnnaMarie McCoy)

Genevieve, an excellent swimmer, is interested in anything that involves physical activity. She uses part of her ESA for speech-language pathology therapy and the educational tools needed to support that.

While Vivian was “born loving science,” AnnaMarie said, she finds herself trying to find something that will spark that interest in Genevieve. Toward that end, AnnaMarie has “melded” their home into a working farm.

“Everything here presents a teaching opportunity or learning opportunity, and they can see it from beginning to end,” AnnaMarie said.

Genevieve watches the chickens go from egg to chick to chicken – the entire lifecycle. In the garden, she follows the plants from seed to harvest.

“And all the struggles with that,” AnnaMarie said, “the positive outcomes and the negative outcomes and the environmental outcomes.”

AnnaMarie said there are “pros and cons” to every education setting.

“This lifestyle suits them best,” she said. “Having this environment and the flexibility in our schedule really suits their interests and their needs.”

Vivian, 14, is nearing driving age, yet she opted to spend the money she could have put toward a car to buy Froggy.

“She eats, lives, and breathes horse stuff,” AnnaMarie said.

“I’m fascinated by the equine species,” Vivian said. “The power and the majesty they hold. I find it very cool that you can do so many things with them and how they've evolved over the years.”

She was thrilled earlier this summer when she was allowed to ride Froggy in the local Fourth of July parade. It was a big step for both of them, Vivian said. She was able to do something away from the farm with Froggy, and he was able to be around a crowd with all the music and pageantry that comes with a parade.

“I was proud that he didn’t freak out,” she said.

Vivan said she plans to attend college and would like a career in marine biology or one that allows her to work with livestock.

For now, she’s content to work part-time at a local horse farm and care for Blue and Froggy.

And she’s grateful her home education setting allows for that.

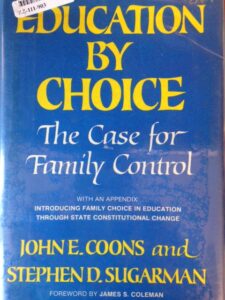

Berkeley law professors Jack Coons (left) and Stephen Sugarman described what we now call education savings accounts - and a system of à la carte learning - in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice.”

John E. Coons was ahead of his time.

Decades before the term “education savings account” became an integral part of the education choice movement, the law professor at the

Jack Coons, pictured here, co-authored "Education by Choice" in 1978 with fellow Berkeley law professor Stephen Sugarman.

University of California, Berkeley, and his former student, Stephen Sugarman, were talking about the concept. In their 1978 book, “Education by Choice: The Case for Family Control,” the two civil rights icons envisioned a model drastically different from the traditional one-size-fits-all, ZIP code-based school system inspired by the industrial revolution:

“To us, a more attractive idea is matching up a child and a series of individual instructors who operate independently from one another. Studying reading in the morning at Ms. Kay’s house, spending two afternoons a week learning a foreign language in Mr. Buxbaum’s electronic laboratory, and going on nature walks and playing tennis the other afternoons under the direction of Mr. Phillips could be a rich package for a ten-year-old. Aside from the educational broker or clearing house which, for a small fee (payable out of the grant to the family), would link these teachers and children, Kay, Buxbaum, and Phillips need have no organizational ties with one another. Nor would all children studying with Kay need to spend time with Buxbaum and Phillips; instead, some would do math with Mr. Feller or animal care with Mr. Vetter.”

Coons and Sugarman also predicted charter schools, microschools, learning pods and education navigators, although they called them by different names.

Fast forward to Florida today, where the Personalized Education Program, or PEP, allows parents to direct education savings accounts of about $8,000 per student to customize their children’s learning. Parents can use the funds for part-time public or private school tuition, curriculum, a la carte providers, and other approved educational expenses. PEP, which the legislature passed in 2023 as part of House Bill 1, is the state’s second education savings account program; the first was the Gardiner Scholarship, now called the Florida Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities, which was passed in 2014.

Coons, who turned 96 on Aug. 23, has been a regular contributor to Step Up For Students' policy blogs over the years. Shortly after the release of his 2021 book, “School Choice and Human Good,” he was featured in a podcastED interview hosted by Doug Tuthill, chief vision officer and past president of Step Up For Students.

“It is wrong to fight against (choice) on the grounds that it is a right-wing conspiracy,” said Coons, a lifelong Catholic whom some education observers describe as “voucher left.” “It’s a conspiracy to help ordinary poor people to live their lives with respect.”

“It is wrong to fight against (choice) on the grounds that it is a right-wing conspiracy,” said Coons, a lifelong Catholic whom some education observers describe as “voucher left.” “It’s a conspiracy to help ordinary poor people to live their lives with respect.”

In 2018, Coons marked the 40th anniversary of “Education by Choice” by reflecting on it and his other writings for NextSteps blog.

He said he hopes his work will “broaden the conversation” about the nature and meaning of the authority of all parents to direct their children’s education, regardless of income.

“Steve (Sugarman) and I recognized all parents – not just the rich – as manifestly the most humane and efficient locus of power,” he wrote. “The state has long chosen to respect that reality for those who can afford to choose for their child. ‘Education by Choice’ provided practical models for recognizing that hallowed principle in practice for the education of all children. It has, I think, been a useful instrument for widening and informing the audience and the gladiators in the coming seasons of political combat.”