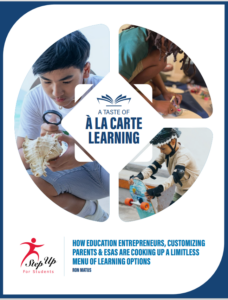

Education is no longer about students sitting in rows of desks from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. And school choice, the term supporters used for years to describe the movement for education options is out. Parent-directed education is in.

That was the call to arms Florida charter school leaders received from one of their earliest supporters on the closing day of an annual gathering convened by the state’s Department of Education.

“We were charged to be laboratories of innovation,” said Jim Horne, a former Florida education commissioner and lawmaker who sponsored the Sunshine State’s first charter school bill. “I challenge you to step out of the proverbial box. If you don’t innovate, you will stagnate.”

Education savings accounts, which allow parents to direct public education funding to private schools, tutoring, curriculum and other options for their children, have been sweeping the country and are now in effect in 19 states.

This has led some national observers to wonder whether charter schools risk losing momentum or becoming political orphans.

Manny Diaz Jr., Florida’s education commissioner, has pushed to counter that chatter. In his keynote address last year, he said education options of all kinds can flourish in the Sunshine State, which is home to the nation’s largest ESA programs and a growing charter school sector.

“We’re capitalizing on this historic school choice and charter school movement. We’re giving parents the ability to choose the best path for their students, regardless of background, regardless of income.”

Last year, the state rechristened its annual convening of charter school leaders as the Florida Charter School Conference and School Choice Summit. This year, private school leaders and educators made up nearly a quarter of the 1,300 attendees.

This year’s event featured main-stage presentations by Success Academy founder Eva Moskowitz, whose New York-based charter school network began eyeing a Florida expansion, as well as presentations on improvements in public-school student achievement, and multiple sessions that highlighted the opportunities growing scholarship programs offer to charter schools.

Last year’s House Bill 1 supercharged the growth of Florida’s ESA programs and created a new Personalized Education Program for students who don’t attend school full-time. That, combined with continued growth of New Worlds Scholarship Accounts for public-school students who need extra academic help, and the existing program for students with unique abilities, creates a substantial opportunity for public schools, including charters, to offer services to scholarship students.

Between those three programs alone, “we’re talking about $1 billion from students that do not have to go to school,” David Heroux, senior director of provider development and relations for Step Up For Students, which manages the bulk of Florida’s K-12 education choice scholarships, said during one session.

School districts, including Brevard and Glades counties, have already begun offering individual courses to scholarship students, with others planning announcements soon or expressing interest in participating.

Adam Emerson, executive director of the Florida Department of Education’s Office of Independent Education and Parental Choice, urged attendees to join the school districts in embracing a la carte learning and the possibilities it has unlocked for charter schools.

“We are entering into a whole new universe of choice,” he said.

Justine Wilson, front row, center, and her husband, Chris Trammel, right, established Curious and Kind as a forest school for part-time, student-directed learning.

SARASOTA, Fla. – After 18 years as an educator in public and private schools, Justine Wilson decided to make a change. She was excellent at her job. In fact, she had just been offered a top administrative position at a top private school. But she didn’t believe mainstream approaches to teaching and learning were the best ones for many students, or for herself.

“I was saying things and doing things that weren’t who I actually was as an educator. I kept getting more and more away from my core beliefs,” Wilson said. “I just wanted to be authentic.”

Wilson wanted:

With the help of Florida’s education choice programs, Wilson did what more and more former traditional educators are doing: She created her own option: a nature-based, student-directed, hybrid homeschool called Curious and Kind Education.

“I love offering something that brings me the most joy,” Wilson said. “Which is being outside with the kids and partnering with their families.”

Curious and Kind offers different programs for different age groups, from toddlers to teenagers. Depending on the program, families can enroll their “explorers” one, two, or three days a week.

Plenty of families love this approach. Curious and Kind started last year with 25 students. This year, it has 90. Nearly all of them use choice scholarships, particularly the Personalized Education Program (PEP) scholarship, an education savings account (ESA) in its second year of existence.

Curious and Kind rents space from a church, but its heart is out back: a two-acre patch of unruly, urban forest, next to a creek that flows from a nature park across the street.

One day last month, 20 explorers ages 5 to 12 took seats on a set of cut logs, arranged in a circle beneath oaks, pines, and palms. Then they got down to business, discussing what they’d like to do over the next few hours. Crochet. Whittle. Make a pizza. Whatever the idea, Wilson and other “facilitators” gently offered suggestions on tools and timing and possible collaborations.

“Our philosophy is ‘Yes. And how do we make it happen?’ “Wilson said.

By early afternoon, most of the explorers had circled back to what they wanted to work on. (Because Curious and Kind didn’t have the ingredients on hand, the pizza had to wait until later in the week.) But first, it was time to play in the woods.

Within minutes, the explorers were building tree forts, making “tea” in a mud kitchen, and trying to identify a species of pseudo-scorpion they found on a slash pine.

At Curious and Kind, play routinely leads to projects.

When the creek was a bit too high for wading, somebody suggested the explorers build little boats instead. (It’s not clear if the idea came from an explorer or a facilitator. “It could have been anybody,” Wilson said. “It’s very democratic.”)

Students try out their homemade boats.

Ice pop sticks and masking tape were on hand. So were twigs and leaves and pine straw. The explorers gave it their best shot, and the initial results were … meh. They pulled their boats from the water to tweak their designs.

The next day, they tried again. This time, they incorporated wine corks that one of the facilitators brought in, plus sturdier and more water-resistant packing tape. This time, they found more success.

“This is what children do when they’re left to their own devices. Humans do this innately,” Wilson said. “They were failing forward, because it was fun.”

The project was also fun because it was theirs.

Agency matters. In one of the classrooms, explorers established their own mini mall. One of them set up a face-painting booth. Another created a line of glittery fingernails. Another manufactured mystery gift boxes, each with its own origami surprise. They even created their own bank, currency, and credit cards.

Wilson quickly suggested the students host a community fair, but “They were like, ‘Why would we want to do that?’ It wasn’t the right time.”

A few weeks later, Wilson pitched the idea again, this time because the Children’s Entrepreneur Market was coming to Sarasota. This time, the students were pumped.

In Florida, the state that’s leading the nation in reimagining public education, Curious and Kind is “school,” too.

It bills itself as a blend of the forest school and Agile Learning Center models. That may not be “traditional” education to some folks, but it has deep roots in thoughtful, alternative approaches.

“We believe in recognizing the innate curiosity of kids and fostering that,” said Chris Trammel, who is Justine’s husband, the director of operations at Curious and Kind, and likewise a longtime educator in public and private schools. “If you’re following your passions, you’re going to take ownership of your learning.”

Curious and Kind represents a number of other choice-driven trend lines.

The “hybrid” schedule is catching on. Florida’s homeschooling population has skyrocketed in recent years, as it has across the country, and more homeschooling families are opting for part-time schools.

Curious and Kind is on the cutting edge of “a la carte learning,” too. Thanks to the flexibility of ESAs, —which can be used for a range of educational expenses, not just private school tuition — more and more parents are choosing from multiple providers.

In Florida, the primary vehicle for that, the PEP scholarship, can serve up to 60,000 students this year, up from 20,000 last year. Thousands of students are also using another Florida ESA, the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities, in a similar fashion.

In Florida, the primary vehicle for that, the PEP scholarship, can serve up to 60,000 students this year, up from 20,000 last year. Thousands of students are also using another Florida ESA, the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities, in a similar fashion.

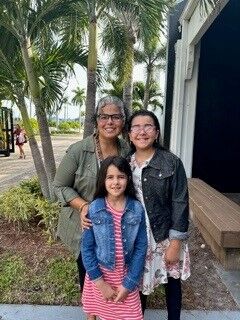

Carolina King’s daughters, Camila, 11, and Giuliana, 9, are among them. Both have special needs that would make it more challenging for them to thrive in traditional schools, said King, who writes a popular blog about parenting and child development.

King believes the student-directed approach is ideal for instilling a lifelong love for learning. Before the family moved to Florida in 2021, Camila and Giuliana attended a Montessori school. When a similar school didn’t pan out after the move, King turned to homeschooling and soon found Curious and Kind.

“They love it there. When the school year was over, they were so sad,” King said. “They said they never want to do summer again.”

King said features big and small make Curious and Kind special. The kids eat and use the restroom whenever they want. Different ages interact with each other. There’s no bullying. More than anything, King can see her daughters pursuing what excites them and learning deeply in the process.

Last year, Camila helped write a Halloween play that the kids performed for each other. She came up with the original idea. Other kids contributed to the script. Still more took on acting roles. Some were so engaged, they worked on the project at home.

“A lot of what happens is a snowball effect,” King said. “The kids feed off each other.”

Curious and Kind and similar alternatives might not be right for every family. But as choice in Florida has expanded, more and more have been flocking to them.

“People have a diversity of interests,” Wilson said. “We should have a diversity of options.”

In July, Jessie Pedraza was reading through posts on a Facebook page for mothers who homeschool their children when she saw three words jump off her screen.

Personalized Education Program.

“I responded, ‘Hello. What is this?” Jessie said.

So Jessie texted one of the moms.

Then they met for coffee.

“I picked her brain and got more information,” Jessie said.

This is what she learned:

Florida students not enrolled full-time in private or public schools can access the Personalized Education Program (PEP) through the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program, which is managed by Step Up For Students. It operates as an Education Savings Account (ESA), which enables parents to customize their children’s education by allowing them to spend their scholarship funds on various approved, education-related expenses.

Florida students not enrolled full-time in private or public schools can access the Personalized Education Program (PEP) through the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program, which is managed by Step Up For Students. It operates as an Education Savings Account (ESA), which enables parents to customize their children’s education by allowing them to spend their scholarship funds on various approved, education-related expenses.

Jessie and her husband, John, who live in Naples, had been homeschooling their daughters Annaliyah (now in the fifth grade) and Gianna (third grade) since 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic first closed schools.

“We said, ‘We can do this. We can provide something better and a little bit more tailored to the kid’s needs,’” Jessie said. “COVID, honestly, is what pushed us, so we went full-time.”

After learning about PEP, which was added to the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for the 2023-24 school year, Jessie applied and was accepted.

“PEP has allowed us to level up our homeschool experience,” she said. “It gives us the opportunity to really create an A-plus homeschool experience versus an A or B-plus.

“It is really growing the homeschool experience.”

Jessie and John have teaching experience from their prior professions.

They use a homeschooling curriculum for reading, spelling, science, history, language arts, and math. They paid for it out of pocket for this school year because it was purchased before they received the scholarship, but the ESA will cover the curriculum in future years.

They use a homeschooling curriculum for reading, spelling, science, history, language arts, and math. They paid for it out of pocket for this school year because it was purchased before they received the scholarship, but the ESA will cover the curriculum in future years.

This year, Jessie and John are using the ESA for field trips and memberships to STEM programs near their home in Naples.

They also use it for the physical education portion of their daughters’ education. Annaliyah is enrolled in martial arts and recently earned her first belt.

“That's been huge,” Jessie said, “because her confidence has just gone up. And that would not have been a possibility if we had not gotten the scholarship.”

Gianna has joined a local gym that has a program aimed at kids, ages 7-11.

“They focus on developing the overall athleticism of kids,” Jessie said. “Gianna is 8. She’s still trying to figure out what she’s interested in. This will focus on athleticism, agility, building muscles. From there, we can get a little more specific.”

Both girls have joined the local 4-H association. Annaliyah is in the cooking program, and Gianna takes crocheting.

“The cooking is actually a year-long project,” Jessie said. She can put together a portfolio and learn about nutrition. These are life skills that she’s going to have, and this became an opportunity because of the scholarship.

“I tell them, ‘You guys can do this, and you guys can do that.’ I don't know if they're as excited (about the scholarship) as I am. I think to them, they're just like, ‘Oh, mom makes it happen.’ But it’s just been a huge blessing for us.”

The cooking and crocheting, the gym and martial arts, and even some of the field trips Annaliyah and Gianna take with other homeschool students in Collier County wouldn’t have been available to them before they received the scholarship.

The cooking and crocheting, the gym and martial arts, and even some of the field trips Annaliyah and Gianna take with other homeschool students in Collier County wouldn’t have been available to them before they received the scholarship.

“When you're homeschooling, you have to look at what are the priorities first, right? And then those extracurriculars come in second,” Jessie said. “So, the scholarship, for us, allows us to place the same kind of priority on the extracurriculars. This is a good overall experience. They’re not missing anything that a student (who attends a school) would have access to.”

Jessie is a co-leader of a local homeschool group with 10 mothers and 30 kids. The mothers know the ins and outs of homeschooling. Jessie is somewhat surprised she didn’t learn of PEP until its second year. When she did, she spoke to parents who received the scholarship and researched it on the Step Up website.

She also attended a PEP meeting in Naples hosted by Step Up program administrators.

“I had all this information, but you always want to go straight to the source, and the source was here,” Jessie said. “[They] solidified it. I said, ‘OK, this is it. This is the direction that we're going,’ and it's been good. Well, it's great, actually.”

Saltwater Studies founder Christa Jewett said when it comes to the potential for education entrepreneurs to create à la carte options in Florida’s choice-driven environment, “The sky’s the limit.”

Editor's note: This story is one of five spotlights included in our latest special report, "A Taste of À La Carte Learning."

So how's this for a science classroom?

These students are snorkeling on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in a place called Jupiter Inlet. They’re enrolled in an à la carte learning program called Saltwater Studies.

Saltwater Studies was started in 2011 by Christa Jewett, a marine biologist who used to work for an environmental consulting firm. Now she teaches students from kindergarten to high school in South Florida’s expanding network of home-schools and micro-schools.

More than a dozen state and county parks function as their classrooms. At one, Jewett secured a state permit so her students could contribute data to a marine life monitoring project.

This is what “school” can look like in a world where entrepreneurs can leverage education choice programs to create innovative options and parents can use those programs to access them.

Until a few years ago, Jewett had to work side jobs because her immersive science lessons alone wouldn’t pay the bills. Then COVID-19 happened. Suddenly, more parents, dissatisfied with traditional schools for multiple reasons, wanted more options.

Now Jewett’s serving 200 students a month. That’s triple the number from 2020 and 20 times the number she started with in 2011.

“It’s gotten so big so fast, it’s surreal,” Jewett said. Last school year, about 15 students used ESAs to access Saltwater Studies. This year, the number is 32 and counting. Now that Florida has universal eligibility for ESAs, even more students and families will be able to access what Jewett and other entrepreneurs are creating.

“Christa’s heart and passion about what she teaches is spot on,” said Juliette Mooney, whose sons, Seven, 10, and Levi, 6, secured ESAs this year. “There’s nothing she doesn’t know about our water.”

Mooney said her boys love Saltwater Studies because they learn better outdoors. “They’re full-on boys,” she said. “When they exercise, they can focus better. We do a lot of learning like this.”

On a windy day last fall, Jewett began the day’s lessons with eight elementary-school-aged students at picnic tables near the water’s edge, beneath cabbage palms and sea grape trees. This was a good spot to see dolphins, rays, and manatees, she told them. But the wind had kicked up turbidity in the water, so visibility wouldn’t be as good as usual.

If they were lucky, though, they might still get a treat: a glimpse of two sea creatures in a symbiotic relationship—a little fish called a goby and a nearly blind little crustacean called a snapping shrimp. Jewett explained that the pair share burrows and protect each other from predators.

“They’re right here!” Jewett told them, pointing to a line of wake-breaking rocks 100 yards away.

Jewett’s instruction was a digestible mix of facts and concepts. Her delivery was infectious. The students couldn’t wait to put on their snorkels and see for themselves.

“So often in the public school system, you're told this is what you have to teach. Because of the size of the system, they have to be regimented," Jewett said. "The bigger it gets, the more boundaries they have to put in place."

“But I have flexibility,” Jewett continued. “That’s what makes this class exciting.”

On the Saltwater Studies website, Jewett explains why she switched careers. From the beginning, the goal was to offer a biblical perspective on the wonders of marine environments. Given the demand, Jewett offers classes with a biblical or secular perspective, depending on what parents prefer. The split is about 60/40. Either way, students gain a deeper understanding of the diversity and amazingness of life on Earth.

Christa Jewett, founder of Saltwater Studies

“Saltwater Studies is the coolest thing ever,” said Jackie Sickels, whose son, Dash, 11, uses an ESA for students with special needs. “It’s a lot more fun way of learning.”

Dash was previously enrolled in public school, but distance learning during COVID-19 was “pointless,” Sickels said. She and some of her cousins decided to home-school their children together, and it turned out to be a positive experience. They learned about Saltwater Studies at a home-school showcase sponsored by a local church.

Jewett’s program turned out to be even better than expected. Dash has learned about everything from manatees to pink moon jellyfish to sea slugs called nudibranchs, all with real-life examples.

Jewett’s approach “checks all the boxes: visual, auditory, hands-on,” Sickels said.

Karina Scarlett’s daughter, Kaylee, 8, has been attending Saltwater Studies for three years. She also uses an ESA for students with special needs.

Jewett is “applying all these science components—measurements and tools and concepts—while they’re working hands-on,” Scarlett said.

On one outing, Kaylee caught an elusive ghost crab. With Jewett’s help, they identified the crab as female, then measured and released it.

Scarlett uses the term “eclectic learning” to describe the home education program she has curated for Kaylee using the ESA. Having the ability to pick and choose exactly what works for her daughter, including providers like Saltwater Studies, is “wonderful,” she said.

“It’s freedom.”

PALM BEACH GARDENS, Fla. – Cristina Bedgood, a 15-year former public school teacher, took two years to craft plans for her own private learning center. She knew she needed 40 students in year one to make it work. But in April, when she held her first open house for Curious Innovators of America, she looked out the front door five minutes before the start time and saw … nobody.

Her heart sank.

Her heart sank.

Thankfully, it floated right back up, because in the next few minutes, 30 families appeared. “And every person who walked in the building said, ‘Oh my God, we need this! ‘ ”

The calls keep coming. Bedgood signed up 10 students on one day in August alone. Most of them use state-supported education savings accounts.

Bedgood said the response has been gratifying – and going her own way as a teacher, liberating.

“I needed to be able to break free. I felt like I was being caged,” Bedgood said, referring to traditional schools. “I knew I could do so much, but I was being limited.”

In Florida, a national leader in expanding education choice, it’s tough to keep up with the growing ranks of former public school teachers who are leveraging choice programs to create their own options.

Bedgood said she came to realize she could help more students by creating her own model – in this case, a K-8 tutoring center focused on math, reading, and enrichment that caters to a wide range of students with a wide range of schedules.

She didn’t come to this conclusion lightly.

Bedgood was the instructional coach at a high-poverty, public elementary school for six years. She found the work “exhilarating.” But she also began to have doubts about the best path forward.

Bedgood said she was effective in part because she had a principal who gave her the freedom to veer from district dictates; to “go rogue” when she thought she needed to. Bedgood said she re-ordered and re-focused some parts of the curriculum, doubled down on others, and better aligned it to state standards. She leaned into response boards for formative assessments. She made widespread use of manipulatives that previously were gathering dust.

Her approach worked. The school’s state-issued grade gradually rose from a D to an A. Math proficiency rose from 47 percent to 72 percent.

But Bedgood said she also saw that principals like hers were rare. And that not everybody had high expectations for high-poverty students.

“I knew it. I watched it. I saw kids who were Level 1’s (the lowest level on Florida’s standardized tests) shoot up to proficiency,” she said. And yet, in some places, “the climate was almost like, ‘These kids can’t do it.’ “

Bedgood asked herself: If I rose through the ranks, would I truly be in position to do what works?

Ultimately, she concluded, there was a good chance she wouldn’t be. So, she looked for the exit. She overcame fears about starting her own operation; persuaded her husband, a firefighter; consulted with experts, including other teachers; and found a good location without too much hassle.

Bedgood describes Curious Innovators as a tutoring center and microschool. She opened in April with two students: Her own kids.

Bedgood describes Curious Innovators as a tutoring center and microschool. She opened in April with two students: Her own kids.

The center is 4,200 square feet, in a trim office building framed by oaks and palms. The interior is colorful and comfortable, with giant, geometric puzzle pieces hanging from the ceiling, all of it designed to stimulate creativity. There are separate rooms for reading, math, and STEM, and multiple stations for students to collaborate.

Bedgood employs five instructors, three of them full time. Two are former public school teachers.

All the students are homeschooled.

Some need tutoring in reading and/or math. Some are there for enrichment. Some mix and match from both. Bedgood emphasizes project-based and inquiry-based learning, but each student’s programming is created in tandem with them and their parents.

Reading and math classes are offered three days a week. Enrichment classes include art, music, drama, debate, creative writing, STEM, and entrepreneurship.

Maria Tobon signed up her daughter and son for math, reading, and science this fall after getting to know Curious Innovators during a three-week summer program. They attend full days on Mondays and Fridays.

One of her children uses Florida’s Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities. The other uses a Personalized Education Program scholarship. Both are administered by Step Up For Students.

“The beauty of a tutoring program like Cristina has built is you can hand pick what you need,” said Tobon, a former Montessori teacher who manages a homeschool co-op.

Tobon said between all her children, she has experienced a full gamut of educational options, from traditional public schools to magnet, charter, and private schools. She decided to homeschool after one of her children was diagnosed with cancer, and the COVID-19 pandemic made traditional schooling too risky.

Homeschooling, she said, turned out to be “absolutely mind-blowing.”

“When I took control … they grew in every sense,” Tobon said. “Going back to a full-time program sounds like jail.”

Kristen Collins wanted part-time schooling for her children, too. Her husband travels a lot for work, and homeschooling allows the family to occasionally join him, without missing a beat educationally.

Bryson, 6, and Aaliyah, 8, both use PEP scholarships. They attend Curious Innovators full days on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays.

“It’s just a great happy medium,” Collins said. And her kids “don’t want to leave. They’re having a blast.”

In some ways, Bedgood’s approach to teaching and learning is mainstream.

She follows the “science of reading” for younger students and struggling readers. She uses standardized tests to gauge proficiency. She tends to follow the grade-level progressions laid out in state standards.

The difference is, she has the flexibility to deviate from those tools, or supplement them, in any way she and the parents see fit.

Collins said that approach is working for Aaliyah, who has struggled a bit in math.

“Cristina recognizes that students learn differently, with different modalities. It’s not one size fits all,” she said. Aaliyah “has only been there two and a half weeks, but I can see she’s getting to these higher levels.”

After experiencing what’s possible outside traditional schools, Bedgood said she couldn’t go back.

Giving parents and teachers options, she said, is the best path to progress.

“I want choice to be the primary form of education,” she said. “The change needs to come from out of the system.”

Drywall is piled three feet high in the attic of Emily and Alan Lemmon’s home in Tallahassee. It was placed there a few years ago, intended for walls as the couple finished the top floor.

But these days the stack serves a different purpose. Surrounded by white sheets used as backdrops and placed directly under nine flood lights attached to the rafters, it’s the stage used by the Tallahassee Homeschool Shakespeare Club, founded by the Lemmons’ oldest child, Genevieve.

“I have a house full of kids, about 25 of them, practicing their Shakespeare lines,” Emily said.

Genevieve Lemmon is the founder and director of the Tallahassee Homeschool Shakespeare Club.

Four of those kids live there – Genevieve, 14, and her siblings Chiara, 12, Dominic, 10, and Declan, 5. The middle two have roles in the yearly Shakespeare plays directed by Genevieve. Declan works as a stagehand, though he might soon earn a part on stage, possibly as the mischievous imp Puck from “A Midsummer Night's Dream,” which according to his oldest sister is a role he was born to play.

Genevieve began the club when she was 11 after watching Tallahassee’s Southern Shakespeare Company perform “Twelfth Night.”

“That kind of lit a fuse,” Genevieve said.

She recruited 10 of her homeschooled friends to act out three scenes from “Twelfth Night,” and soon her home was Tallahassee-upon-Avon. Alan was building sets, Genevieve was sewing costumes with her grandmother, and everyone was reciting William Shakespeare.

How do you get an 11-year-old hooked on the works of The Bard?

“We don’t own a TV,” Emily said.

And every room in the house is lined with bookcases stuffed with books.

The back yard leads to wetlands explored by the children as they satisfy their curiosity about anything that grows, crawls, swims, and flies.

Emily and Alan are both professors at nearby Florida State University, and this is what they envisioned when they decided to homeschool their children. Emily was homeschooled and thrived in that education setting. She wanted the same for her children because she liked the freedom of customizing the curriculum to each child’s needs and interests.

“I like the way that homeschooling gives you more family time,” Emily said. “It helps build a really close-knit family, and parents can have more influence on the formation of their kids. I also thought my husband and I could do a better job educating them than a lot of schools because we can give them one-on-one attention.”

Last school year, the Lemmons qualified for the Personal Education Program (PEP) that comes with the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship (FTC), managed by Step Up For Students.

That was the first school year homeschooled families were eligible for PEP. The scholarship is an Education Savings Account (ESA) for students who are not enrolled full-time in a public or private school. This allows parents to tailor their children’s education by allowing them to spend their scholarship funds on various approved, education-related expenses.

For the Lemmon kids, that’s a heavy dose of music lessons. They are all taking lessons in piano and a string instrument. All are members of the Tallahassee Homeschool String Orchestra, while Genevieve and Chiara are also members of the Tallahassee Youth Orchestra.

All PEP students are required to take a yearly, state-approved, norm-referenced test. (The list of tests can be found here.) The Lemmons take the Classic Learning Test.

PEP helps pay for curriculum, school supplies, books, summer camps, and music lessons.

“We’re trying to expose them to lots of different fields because they're trying to figure out what they're most interested in,” Emily said.

Chiara’s interests lean toward the sciences. She’s also developing an interest in farming and is now raising 17 young chickens in hopes of beginning her neighborhood egg business. She’ll call it Chiara’s Cheeky Chicks or Chiara’s Cluckers.

Chiara is also scheduled to take a farming internship this year.

Genevieve is mechanically inclined. She can take apart and reassemble a bicycle. She once disassembled a door in the family’s van and fixed what was rattling.

“She might have the makings of an architect or an engineer,” Emily said.

Or a Shakespearean scholar.

Genevieve took an online course this summer on “The Merchant of Venice,” taught by a Shakespearean author.

Her favorite plays are “Twelfth Night” and “King Lear.” When asked for her favorite Shakespearean line, she answered with the back-and-forth between Beatrice and Benedick in “Much Ado About Nothing.”

The Lemmons don’t own a TV and the kids don’t have iPhones, because Emily and Alan don’t want their children spending time staring at screens. They’d rather their children read books and explore the outdoors to stimulate their minds.

“So, you asked why an 11-year-old got interested in Shakespeare, it’s because her brain wasn't supersaturated with flashing lights and exciting noises and materialistic commercials. And she was quiet enough to be able to focus on what Shakespeare meant,” Emily said.

Directing has been a learning process for Genevieve. Mostly, she’s learned how to lead a cast. Along the way, she learned she could help shy or introverted cast members develop confidence by giving them bigger parts.

“I give them harder parts and they rise to the occasion each time,” she said.

Genevive said it was hard at first getting other homeschool students interested in Shakespeare. She fixed that with post-rehearsal pizza and ice cream parties. The afterparties are now called Sugar Shakes.

For Christmas last year, Genevieve received a director's chair and a megaphone.

“It was pretty cheesy in the beginning,” she said, “but now they know if they sit on my chair they're going to get in big trouble.”

In four years, the Tallahassee Homeschool Shakespeare Club grew from the original 10 members to its current 25. All are homeschooled and all received PEP scholarships.

Genevieve said being homeschooled is the catalyst behind her love of Shakespeare.

“I just like how it gives me more flexibility and it gives me more time to pursue my interests,” she said. “I think if I'd been in a (district) school system up to this point, I wouldn't have probably been exposed to Shakespeare and I wouldn't be directing plays now.”

Gabriel Lynch III was born five months early and weighed 1.8 ounces when he entered this world fighting for his life. He spent his first three months in an Orlando hospital.

When he was just weeks old, he was removed from an incubator and airlifted to a Tampa hospital for heart surgery. By then, Gabriel already had surgery on his eyes. He developed a grade 4 brain bleed, which doctors told his parents, Krystle and Gabriel II, could lead to cerebral palsy.

It didn’t.

“He had a lot of issues,” Krystle said, “but God is good.”

Gabriel Lynch used the ESA from his PEP scholarship for piano and guitar lessons.

Krystle chronicled it all in her book, “Miracles do Happen. A mother's journey through preterm birth, loss and triumph.”

A picture of tiny Gabriel dominates the cover. He is hooked up to tubes with bandages over both eyes. He’s barely bigger than the length of his mom’s two hands as she holds him.

A current photo of Gabriel might include a piano, which he can play.

Or him holding the book about his faith, which he wrote when he was 13.

Or a cap and gown.

Gabriel, who turns 19 in August, graduated high school in May, having been homeschooled during the past school year with the help of the Personalized Education Program (PEP) that comes with the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship (FTC). The FTC is managed by Step Up For Students.

Signed into law in 2023 as part of HB1, PEP provides an Education Savings Account (ESA) for students who are not enrolled fulltime in a public or private school. The ESA allows parents to customize their children’s education by spending their scholarship funds on a variety of approved, education-related expenses.

“The PEP scholarship has been a blessing,” said Krystle, who along with her husband is a pastor at a local non-denominational church.

All three of her sons received PEP scholarships last year. Before that, they received FTC scholarships and attended private schools near their Apopka home. Gabriel will attend Seminole State College in Lake Mary this fall, while his younger brothers – Kingston (eighth grade) and Zechariah (sixth grade) will continue to receive PEP scholarships.

“There were just certain things about their education that my husband (Gabriel II) and I needed to take control of,” Krystle said. “As a parent we know, and we want to control their education, so we decided to homeschool them.”

What Krystle wanted more than anything else was the ability to tailor the education toward each of her sons’ interests and needs.

“They all have different learning paths,” she said.

For Gabriel, that was an opportunity to use the ESA for dual enrollment. He took English, psychology, and music appreciation courses through the dual enrollment program at Oklahoma Christian University.

He also used his ESA for piano, guitar, and voice lessons and a tutor he worked with three times a week. His curriculum included Spanish I and II, music, statistics, and personal finance.

Kingston has improved in math since being homeschooled because he now has access to a tutor, both during and after school. He will take computer science and coding this school year. Krystle would like him to dual enroll once he reaches high school.

Zechariah is academically gifted, according to his mom. He studied above grade level as a fifth-grader and will do so again this year when his course load will include advanced classes. Krystle is trying to prepare him for advanced placement classes when he reaches high school.

Kingston, Zechariah and Gabriel have thrived academically with the help of the PEP scholarship.

Krystle is also researching hybrid learning opportunities for Kingston and Zechariah.

“That's a game-changer right there because my kids want social interaction, but I don't want them to be in school all five days,” Krystle said. “I can send them to school once or twice a week and they can learn a subject during that time, but then the rest of the subjects I teach at home.”

All PEP students are required to take a yearly state-approved norm-referenced test. (The list of tests can be found here.) The boys took the Stanford Achievement Test Series, Tenth Edition (SAT10).

“We just love the fact that PEP gives students the opportunity to be their best selves,” Krystle said. “They can have guitar lessons. They can have singing lessons. They can have acting lessons. They can have reading tutors, language arts tutors.

“The sky’s the limit, and we just love that.”

Music is a big part of Gabriel’s life. He played the piano in an AdventHealth commercial and placed first in the Sacred Heart Music Competition in May.

Music is a big part of Gabriel’s life. He played the piano in an AdventHealth commercial and placed first in the Sacred Heart Music Competition in May.

He would like to be a composer.

“I’ve had a passion for music since I was 8,” he said.

He also has a passion for social media, with more than 17,000 followers on TikTok and nearly 5,000 on Instagram (GABE4_christ). He has a YouTube channel and a podcast.

His book, “The Destined Place of Living,” is about his faith. He is an ordained minister and a motivational speaker for youth.

Through the Florida Parent-Educators Association, which serves homeschooled families, Gabriel was able to attend a prom and participate in a graduation ceremony in May at the Gaylord Palms Resort and Convention Center in Kissimmee. That’s also where he won the music competition.

It brought an end to his high school education and his one year being homeschooled.

“I will say that homeschooling was one of the best decisions that my parents have made,” Gabriel said. “It gave me more freedom to study music.”

Editor's note: This story is one of five spotlights included in our latest special report, "A Taste of À La Carte Learning."

Florida has long had a critical shortage of public school science teachers. But growing numbers of students in South Florida’s booming alternative education networks are learning science from a real-life scientist.

Dr. Neymi Layne Mignocchi has two master’s degrees in biology and experimental psychology and a Ph.D. in neuroscience. She worked for six years as a molecular biologist at the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience. Her research accomplishments include developing a genetically encoded sensor for oxytocin, which plays a critical role in childbirth.

After the birth of her first child four years ago, Mignocchi decided to home-school and embark on a career path that would combine her love for science with her love for teaching.

Eye of a Scientist customizes experiential science lessons for students who are either home-schooled or in micro-schools. Most of them are in elementary grades.

Mignocchi began three years ago with 30 students. Now she’s teaching more than 150. The demand is so great that Mignocchi recently hired a graduate student in science to help teach some of her classes, and she’s interviewed a second for the likely expansion ahead.

"This is progressing faster than I ever expected, "She said.

Mignocchi’s goal is to inspire students and teachers.

She wants the former to know that they, too, can grow up to be scientists and the latter to know that there are other ways to deliver science instruction that might be more effective for students and rewarding for themselves.

On a muggy morning last fall at Tree Tops Park in Davie, about 10 miles from Fort Lauderdale, Eye of a Scientist was in full swing with a dozen kids in grades K-2 and their gently hovering parents.

This day’s lesson was all about carbon.

Mignocchi started with the big picture, telling the kids about matter, atoms, and subatomic particles. At the same time, she doled out craft supplies for the fun part: building a 3-D replica of a carbon atom. She proceeded to spell out directions for constructing the atoms out of pipe cleaners and colored beads while peppering the students with more facts and concepts.

The Eye of a Scientist had The Flow of a Maestro. Somehow, every student stayed focused on what they were building and what they were learning.

“Carbon is the backbone of life,” Mignocchi told them. “Without carbon, life would not exist. Without carbon, you would not exist.”

Repeating definitions and fun facts was part of the lesson.

“Do bananas have carbon in them?” YES!

“Do apples have carbon in them?” YES!

“Do pancakes have carbon in them?” YES!

At the end of the lesson, each student had a colorful model of a carbon atom, complete with six electrons, six protons, and six neutrons, that they could hang in their homes. They also had their first lesson in chemistry which Mignocchi would build on with future lessons.

“You have to prime these students’ brains,” she said. “You have to do it when they’re the most curious, when they’re younger.”

"Teaching in this manner helps students connect with the information because they're literally experiencing it in real life," she continued. "They're learning to understand the world they're living in, in a better, more direct way in comparison to sitting down in the classroom and just reading some paragraph about it."

Many of the students at the micro-schools and co-ops that Eye of a Scientist orbits use ESAs. Mignocchi recently became an approved provider through Step Up For Students, the nonprofit that administers the state’s choice scholarships (and employs the author of this white paper), so parents can channel ESA funds to her directly rather than pay out of pocket and seek reimbursement. Her expectation is that this will allow her to serve an even broader range of students.

Mignocchi’s life story informs her mission. Her family fled Venezuela for America when she was 8 years old, and she went on to become a straight-A student in public schools. But she found out when she got to college that she was not ready to meet basic expectations in science.

Later, Mignocchi spent time tutoring public school students in science and found that they, too, were woefully unprepared.

With Eye of a Scientist, Mignocchi aims to fill those gaps, particularly with low-income students. That’s another reason, she said, she supports ESAs. They will allow more low-income families to access learning alternatives that may be best for their kids but in the past were out of reach.

“What I want,” she said, “is a level playing field.”

Kassandra Rodriguez uses the Florida Family Empowerment Scholarship for Unique Abilities, an education savings account program, to create customized learning programs for her sons, Zachary, left, and Cameron. They are visiting a park to learn the science behind natural springs. They have also gleaned for mangoes, gone on nature hikes and participated in virtual classes.

Editor's note: This post provides a parent's perspective to supplement our recent white paper, "A Taste of À La Carte Learning," which spotlights the rise of unconventional learning options in Florida. Thousands of Sunshine State parents are now using state-supported education savings accounts to create unique learning programs for their children.

STUART, Fla. — Kassandra Rodriguez thought she could teach her son Zachary to become a better writer, but no. She gave him prompts she thought would spark his creativity – like, If you could make up any flavor of ice cream, what would it be? – only to get one-sentence responses.

Both of Rodriguez’s children, Zachary, 11, and Cameron, 8, have special needs that qualify them for the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Unique Abilities. That ESA, created by the state 10 years ago, gives families the flexibility to direct funding to various educational programs and providers. On average, each one is worth about $10,000 a year.

After doing some research, Rodriguez found a writing teacher on an online platform, Outschool. The teacher lives in Canada. Only three other students attended the one-hour-a-week slot (including, amazingly, another ESA kid from Florida). And Zachary loved it. Sometimes the teacher would kick things off by reading from a graphic children’s novel – say, “Wings of Fire” – then engaging students in a conversation.

“That seemed to get the juices moving,” Rodriguez said.

Soon, Zach was writing inspired, two- to three-page essays. Even better, he could take the class in the car while Rodriguez drove him and Cam to other educational activities.

Stretch that one example to more than a dozen other providers for Rodriguez’s sons, and you begin to see what’s possible with ESAs and a la carte learning.

Florida is on the cutting edge of what’s coming.

Last year, the Sunshine State moved to universal education choice. But even before that historic shift, thousands of parents were customizing their child’s education, using ESAs to mix and match from a growing universe of providers. Together, these parents and providers are pioneering new approaches to teaching and learning that bypass traditional schools. Homeschoolers have been doing that for decades. But now, with state support, even more families can give it a go, in numbers big enough to ripple through the entire system.

With ESAs, “You can make whatever education program you want,” Rodriguez said. “After meeting more people, and seeing what’s out there, I realized I can make things happen. I can have what I want for my boys.”

What Rodriguez wants includes two of the la carte providers featured in our new white paper, “A Taste of A La Carte Learning.” Both Surf Skate Science and Eye of a Scientist offer popular and hands-on approaches to science instruction.

But the family’s a la carte adventure hardly ends there.

Zachary is diagnosed with dyslexia, ADHD, and a speech disorder. Cameron also has a speech disorder.

Before the family moved to Florida from Iowa in 2020, Zachary had been enrolled in a private school, where he experienced bullying and fell behind academically. That experience is what led Rodriguez to try homeschooling.

Rodriguez uses her sons’ ESAs to pay for speech therapy from the same therapist they used in Iowa, only now they access the services online. Ditto for Zach’s dyslexia tutor. Both of those individuals have credentials that make them eligible for Florida ESA funding.

Rodriguez is also using the ESA to “unbundle” individual classes at nearby schools.

ESA enthusiasts have been talking up this possibility for years. In Florida, thousands of schools, including public schools, could unbundle their services if they wanted. A few examples of that are happening here and here.

Rodriguez asked several microschools if they’d let her boys take a few classes instead of enrolling full time. Some rejected the idea. But a couple said, “Yeah, we can do that.”

At one, both boys took several classes, including “simple machines” for Zach and “collaborative building” for Cam. Both involved science and engineering instruction. At the other, both boys took art and theater. The latter class met weekly for two hours for a semester, and it culminated in a community production of “Aladdin.”

There’s more. The ESA pays for Zach’s membership on a competitive traveling LEGO robotics team. And for both boys, it’ll soon pay for recreational league lacrosse and piano lessons with a music teacher.

Rodriguez uses the ESAs for art supplies, science kits, a book club, and BitsBox, a subscription service that teaches computer coding. She’s also purchased a variety of home education curricula and supports, including Power Homeschool, All About Reading, Singapore Math, and Story of the World.

“I overlap some curriculum because I’m afraid I’m leaving something out,” she said.

Kassandra Rodriguez and her sons are often on the go. One program allows Zachary to learn while she drives the boys to other activities that make up their customized learning programs.

The ESAs, Rodriguez said, incentivize bargain hunting. For example, she considered enrolling her boys in a writing class at a third microschool. But the classes cost $70 an hour, while the Outschool course was $14 an hour. She and the boys also tried out another writing teacher – this one in England – but they didn’t think she was as engaging as the one in Canada.

Blazing trails on the choice frontier isn’t easy.

Zach and Cam’s schedule requires a lot of time and mileage. Their programs and providers are scattered across three counties. Some are an hour from their house.

Rodriguez is a stay-at-home mom, in part because a traffic accident a decade ago resulted in long-term injuries that keep her from working. But it’s a mixed blessing, because the situation has allowed her to devote more time to her kids’ educational needs. Also, Rodriguez’s husband is a surgeon. She knows her family can pay upfront for educational expenses and await reimbursement from the ESA in ways that some families can’t.

Still, Florida’s increasingly choice-driven education system is moving toward greater equity. Every year, more families, particularly those disadvantaged by poverty or disability, gain more power to direct education dollars the way they think is best.

Rodriguez has no doubt this approach works for her family.

She frequently gives her sons tests, and they often showcase their knowledge with projects and presentations. Rodriguez also recently used ESA funds for her boys to take the Iowa Test of Basic Skills, a common standardized test. She said she wants to know how they’re doing relative to students their age and whether her approach is working.

Florida law does not require students like Zach and Cam, who are using the FESUA scholarship, to take a standardized norm-referenced test in reading and math. However, such testing is required for students using the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options, and the Personalized Educational Program scholarship. The latter is a new ESA, created in 2023, for students not enrolled full-time in public or private schools and whose parents are customizing their education programming.

Rodriguez said she knows from other assessments that Zach is now reading in the 80th percentile for his age, far ahead of where he was in his prior school.

“I like that we can learn what we want – and at our own pace,” she said. “I saw Zachary struggle a lot with his dyslexia. Now he’s right where he’s supposed to be.”

Being able to access what Zach needed, when he needed it, was big. “Whatever it is, we can nip it in the bud,” Rodriguez said. “We don’t have to wait. It’s instant. We can just get a tutor and go.”

Flexibility has other benefits.

Last year, the family made multiple trips to Texas to see Rodriguez’s father before he passed away. Each time, they stayed a week or two, quickly making arrangements that might have been more difficult for a family tied to traditional schooling.

Rodriguez has told her boys they can go to a traditional school, and she’s shown them some possibilities. But so far, they have shown no interest. Truth be told, they think some of the traditional schools look like jails.

“With the amount of freedom and the amount of things we’ve gotten to do,” she said, “I don’t think we could go back.”

One of the best education stories in America is the shift from school choice to education choice. The best place to see it is an hour north of Miami.

Humming, hustling South Florida – and Broward County in particular – has rightly earned national buzz for its blossoming array of microschools. But as we highlight in a new white paper, the region is also home to another fascinating new species of little learning option: the a la carte provider.

A la carte providers focus on a single subject or niche such as coding, cooking, or science. In South Florida, dozens of them are already serving thousands of students.

Many partner with microschools to complement their programming. Others are mixed and matched by homeschool parents alongside other providers. The potential variants and combinations are endless.

To get a sample of what these providers are doing, check out this video at the top of this post.

The rest of America might be amazed to see public education look like this. In Florida, we’ve seen it coming.

Over the past 10 years, thousands of Florida parents have been pioneering state-supported a la carte learning, ever since Florida created its first ESA. Now with education choice universal, tens of thousands of parents are joining them.

To be sure, many parents will continue to choose the whole package of a school. In choice-rich Florida, those options are getting better all the time. But if, for whatever reason, parents want to personalize a learning program for their children, they can choose that path, too.

South Florida is showing what’s possible when they do.