The category is “Lifelong dreams.”

These are the clues.

Many find this experience fun, exciting, and a little scary.

What is being on “Jeopardy!”?

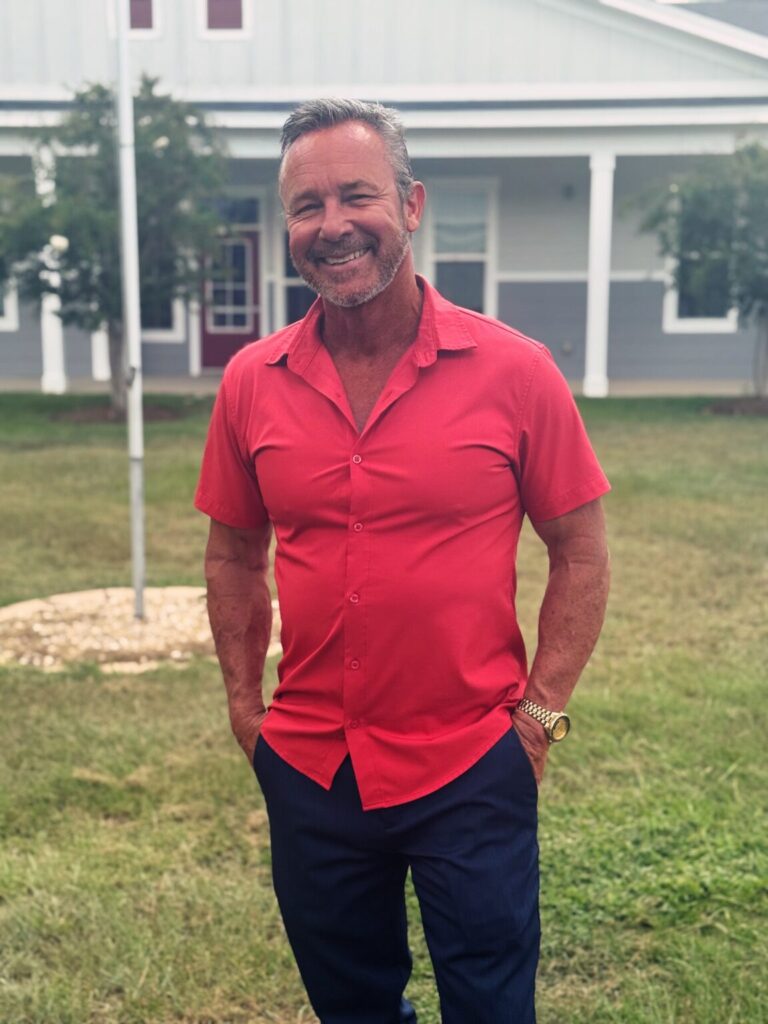

The answer is correct if you’re Michael Kavanagh, principal at Holy Family Catholic School, a K-8 parochial school in Jacksonville.

For as long as Michael can remember, he wanted to appear on “Jeopardy!,” the game show where the answers are given, and the contestants guess the questions. A dream that became a goal when Michael reached high school became a reality when he appeared on the show that aired on Nov. 24.

Michael placed second among the three contestants. He was a perfect 12-for-12 in his answers, including “Final Jeopardy!,” when he was the only one to successfully answer the question. He earned $12,600.

“To be able to say that I accomplished something that I've wanted to do since I was a kid, to be able to actually pull it off and get on the show, that was really just a dream for me,” Michael said.

All but a handful of Holy Family’s students attend the school with the help of a Florida education choice scholarship managed by Step Up For Students. Many watched their principal live out his dream, which made Michael the big man on campus when school resumed after the Thanksgiving break.

And maybe a role model.

“Step Up exists to give children opportunities, to give children a chance to go to a great school and get a great education,” Michael said.

And with that education, well, they too can someday be on “Jeopardy!,” if that’s a goal they want to chase.

“That's what I hope our students see the value in,” Michael said. “I didn't use my athletic abilities. I didn't use my strength or anything like that. I was fortunate enough to go to great schools and learn from great teachers, and I used that knowledge to pursue something that I really loved.

“I think it just shows you that when you have an opportunity, and when you have a dream, and you want to follow it, all these things are possible. So, I do hope that maybe being a role model for someone as a ‘Jeopardy!’ contestant, that's maybe a little bit of a nerdy thing to do, but I do hope it shows the kids that there's value in learning and there’s value in pursuing your dreams.

“It's good to be smart.”

To be selected for “Jeopardy!,” Michael had to pass an online test, then an interview. He had taken the test several times, but this was the first time he was interviewed. In September, he received the call. He would be on the show that was taped Oct. 21.

What is ecstatic?

Michael was told by the show’s producers that 70,000 people take the test each year, but only 450 make it to the show.

“Just being there, you’re in pretty elite territory,” he said.

Michael and his wife, Allison, flew to Los Angeles for a three-day trip. They had to keep the results to themselves until after the show aired.

While Michael didn’t win -- Harrison Whittaker from Terre Haute, Indiana, extended his winning streak to 10 games that day – he was the only one who answered every question correctly.

Other than reviewing the names of Shakespeare characters, U.S. vice presidents, and capitals of foreign countries, Michael said he didn’t study for his big moment. It’s nearly impossible when the show’s producers can pick from a nearly endless list of categories, or, as they did that day, create one where the contestants were given two words and had to change the last letters to form another word.

Michael entered with the random facts accrued over a lifetime of being curious.

“It was just stuff that I've picked up over 40 years of listening, and reading, and studying,” he said. “I'm very blessed with a mind that is always curious and remembers facts that I find interesting. For me, I think everything is interesting.”

It was a combination of facts that led him to the correct answer to “Final Jeopardy!,” the last question of the show and the one that often determines the winner.

The clues:

He wasn't yet a U.S. citizen when he was named an All-American and won two Olympic gold medals for the country.

Michael had 30 seconds to answer.

“I didn’t actually know the answer,” Michael said.

But he knew Jim Thorpe was a Native American, and he knew Thorpe was an Olympic champion, and knowing what he does about American history, he figured Native Americans were probably not considered American citizens at that time.

Who is Jim Thorpe?

“I was able to piece together all of those little bits of information to come up with a really confident guess as to what the answer was,” Michael said. “So, it was a lot of problem-solving, too. A lot of ‘Jeopardy!’ is not, ‘Do you know facts?’ It's, ‘Do you know this fact, and can you use it to lead you to something else?’ ”

“Jeopardy!” tapes a week's worth of shows on Mondays. Michael’s show was the first one that was taped. Afterward, he sat in the audience with Allison and watched two more shows.

Each show is 30 minutes, but because of commercials, contestants are on air for only 22 minutes. Add a few practice questions before taping began, the excitement of being on the iconic “Jeopardy!” set, and the mental energy needed to come up with answers in a split second, and Michael was a little worn out when it was over.

“It’s a competition,” he said. “It's not athletic, but you definitely feel like your body has gone through something. Your brain was spinning, and your heart was racing, and then it's over, and you take a deep breath, and you realize that's it. I'm done. And that was incredible.

“Honestly, it's more like riding a roller coaster, and you get off, and you think, ‘Well, that was fun and exciting and a little scary.’”

HAVANA, Fla. – It was a typical July afternoon in Florida’s Panhandle. The air was hot and sticky, and the sun hid behind the dark gray thunder clouds building to the north of Robert F. Munroe Day School in Havana.

A warm breeze kicked up, signaling the approaching late-day storm.

The students who darted about earlier during summer camp, and the staff and teachers who spent their day on campus preparing for the upcoming school year, were mostly gone.

Andy Gay, head of school, remained. So did Shanna Halsell, director of advancement and marketing. They spent the better part of the day with a visitor, explaining the efforts necessary to keep Robert F. Munroe Day School (RFM) open, despite financial shortcomings, an exodus of teachers, and declining enrollment that not too long ago threatened to close the private pre-K-12 school.

But that gloomy forecast never happened.

In Gay’s first three years on the job, enrollment has increased, and test scores are on the rise.

Several factors came into play for the turnaround, including the expansion of Florida’s education choice scholarship programs managed by Step Up For Students.

“The Step Up scholarship saved this school,” Gay said. “This school has always been on the verge of shutting down, and we’d have closed without it.”

But RFM’s story is more than just the creation in 2022 of the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options, which increased the income requirements for eligible families, making a private school education more affordable to families.

Parents need more than money to send their children to a private school. They need a reason to send them there.

And that’s where Gay comes in. He is a graduate of RFM. So is his wife, and so are his two sons and his daughter.

“We’re a Munroe family,” Gay said. “I love this place. It has a soft spot in my heart.”

That’s the reason RFM’s board of trustees sent an SOS to Gay before the start of the 2022-23 school year.

“We needed him,” Libby Henderson, the immediate past president of the school’s board of trustees, said.

A native of Gadsden County, Gay has deep roots in the community. And, as a former teacher, coach, and administrator in the county school district, Gay is well-versed in how to run a school.

Also, he was available.

Sort of.

Gay had just retired after 32 years in education. He was ready to spend his days fishing and playing with his grandchildren.

That lasted two weeks.

“He indicated he was interested and could be talked out of retirement,” Henderson said.

Gay, who always wanted to run a school, accepted the offer, telling the trustees that he would work for two years. This year is his fourth as head of school.

“I don’t know,” he said, “I fell in love with the job.”

Eventually.

Gay admitted that what he found when he took over was not what he expected. The test scores for reading and math were below grade level.

“I saw a lot of disturbing data, and I knew that there had to be some drastic reform,” he said.

Where to start? The faculty.

Gay filled the vacancies with a mix of seasoned teachers and college graduates.

“It's always been my philosophy that there's no one more important than the teacher in the classroom,” Gay said. “So, I got busy trying to hire people that I knew would get the job done, that I could trust, that I knew.

“With the young teachers, I felt that we could give them the support they needed and turn them into good teachers.”

Gay has coached football and track. He won back-to-back state track titles and came within three points of winning a third straight. He knows how to build a staff of assistant coaches. You hire coaches for their expertise and let them coach.

It’s the same with the teachers.

“The cool thing about Andy that I love is he’ll help you if you need help,” said Anthony Piragnoli, who is in his sixth year at RFM and teaches high school English and coaches the middle school football team. “Now, if you're a new teacher and you kind of need some help, he'll definitely help you out and give you all the resources and all the tools you need. But if you're more experienced, he kind of lets you, I don't want to say do your own thing, but he gives you the freedom to teach the way you want to teach.”

Of course, nothing is more important to a school than the students themselves. To raise the academic bar, Gay and his staff created a welcoming, yet demanding culture.

“It’s all about the expectations you put on the kids,” he said.

And the expectation was that they would become better readers.

Gay instituted DEAR Time, which stands for “Drop Everything And Read.”

A first-grade teacher came up with the idea for the Bobcat Buddy Program, which pairs upper school students with lower school students for mentorships and companionship.

That led to Bobcat Buddy Book Day, where upper school students bring a book or check one out from the library to read to their lower school buddy.

“You go out on campus, and you see kids lining the sidewalk or on the playground, and the big buddy is reading to the little buddy, and I think that is wonderful,” said Dawn Burch, director of education.

The programs work. Two years ago, only 48% of RFM students were reading at grade level. That has increased to 73%.

Halsell’s data shows the school experienced 93.8% growth across the board in reading, math, and science since Gay took over. Last year, 13 of 30 seniors graduated with associate's degrees through the school’s newly implemented dual enrollment program.

But it takes more than just the teachers to get students to work harder. The parents have to buy in, too.

“I want partnerships between parents and teachers,” Gay said. “It can’t be adversarial. I found it makes a huge difference in the overall academic growth of the child when there is a partnership.”

Toward that end, parents are always welcome on campus. Teachers are encouraged to call parents when their child does something positive in class.

“We can call about good stuff, too,” he said.

There is an excitement around RFM that hadn’t been there in years, Henderson said. Last year’s alumni golf tournament raised $25,000, which went toward the school’s curriculum. Halsell works tirelessly to reconnect with alumni and build a network of donors. She recently announced that the school secured a $500,000 grant for its STEM program.

The school sits on 44 acres with plenty of room to expand. A new gymnasium would be nice.

Those rain clouds that appeared over the school on that July afternoon did little more than threaten. Much like the metaphorical storm clouds that were forming when Gay took the job.

“He’s done a phenomenal job,” Henderson said.

Two years turned into four for Gay, and four can turn into who knows how long.

“I feel like I will stay here as long as I continue to see progress and I continue to feel good about this place,” Gay said. “Right now, I feel like we're on the verge of some greatness.”

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. – Four years ago, Phil and Cathy Watson were distressed and desperate. Their daughter Mikayla, then 12, was born with a rare genetic condition that led to physical and cognitive delays. With her school situation getting worse by the day, they needed options, now.

The Watsons were open to private schools. But they couldn’t find a single one near their home in metro D.C. that met Mikayla’s needs. They even looked in neighboring states. Nothing.

One day, though, Phil varied his keyword search slightly, and something new popped up:

A school for students with special needs that had low student-to-staff ratios, transition programs to help students live independently, even an equine therapy program.

The Watsons feared it was too good to be true. Even if it wasn’t, it was 700 miles away.

A destination for education

Florida has always been a magnet for transplants. It’s tough to beat sunshine, low taxes, and hundreds of miles of beach. But as Florida has cemented its reputation as the national leader in school choice, the ability to have exactly the school you want for your kids is making Florida a destination, too.

In South Florida, Jewish families are flocking from states like New York to a Jewish schools sector that has nearly doubled in 15 years. But they’re not alone. Families of students with special needs are making a beeline for specialized schools, too. The one the Watsons stumbled on has 24 students whose families moved from other states – about 10% of total enrollment.

The common denominator is the most diverse and dynamic private school sector in America, energized by 500,000 students using education choice scholarships.

According to the most recent federal data, the number of private schools in Maryland shrank by 7% between 2011-12 and 2021-22. In Florida, it grew by 40%.

“What Florida is offering is just mind blowing compared to Maryland,” Phil said. “If a story like this ran on the national news, people would be beating the door down.”

‘The kid who never spoke’

Phil and Cathy Watson have six children, all adopted. They range in age from 1 to 39. All have special challenges.

“God picked out the six kids we have,” said Cathy, who, like Phil, is the child of a pastor. “We feel very strongly that we were called to do what we do. Our heart says we have love to give and knowledge to share. These kids need that, so it’s a match.”

Mikayla is their fourth child. She was born with hereditary spastic paraplegia, a condition that causes progressive damage to the nervous system.

She didn’t begin walking until she was 18 months old. Even then, her gait continued to be heavy-footed, and she was prone to falling. Her speech was also, in Phil’s description, “mushy,” and until she was 12, she didn’t talk much.

In many ways, Mikayla is a typical teen. She loves steak and sushi and Fuego Takis. Her favorite books are “The Baby-Sitters Club” series, and her favorite movies include “Beauty and the Beast” and “Beverly Hills Chihuahua.” Many of her former classmates, though, probably had no idea.

In school, Mikayla was “the kid who never spoke.”

Checking a box

As Mikayla got older, she and her parents grew increasingly frustrated with what was happening in the classroom. “She was being pushed aside,” Phil said.

Teachers would tell her to read in a corner. Between the physical pain from her condition and the emotional turmoil of being isolated, she was crushed. Sometimes, Phil said, she’d come home and “unleash this fury on my wife and I.”

The pandemic made things worse. In sixth grade, Mikayla was online with 65 other students. Then, three days before the start of seventh grade, the district said it no longer had the resources to support her with extra staff. Instead, she could be mainstreamed without the supports; enroll in a private school; or do a “hospital homebound” program.

The Watsons chose the latter. Three days a week, a district employee sat with Mikayla, going over worksheets that Phil said were “way over her head.”

“All it was,” he said, “was checking a box.”

Just in the nick of time, the school search turned up a hit.

Florida, the land of sunshine and learning options

What surfaced was the North Florida School of Special Education.

“From just the pictures, I’m thinking, ‘This looks legit,’ “ Phil said. “Both of us are like, ‘Wow.’ “

When the Watsons called NFSSE, as it’s called for short, an administrator answered every question in detail. This was not the experience they had with some of the other private schools they called.

At the time, Phil owned a home building company, and Cathy worked for a counseling ministry. They lived comfortably. But they were also paying tuition for another daughter in college.

Thankfully, the administrator told them Florida had school choice scholarships. For students with special needs, they provided $10,000 or more a year.

The Watsons couldn’t believe it. They were familiar with the concept of school choice but didn’t know the details. Maryland does not have a comparable program.

The administrator also told them NFSSE had a wait list. But the Watsons had heard enough.

A fortuitous phone call

A few weeks later, they were touring the school.

The facilities were stellar. Even better, the administrator leading their tour knew the name of every student they passed in the hallways. “We were blown away,” Phil said. “They truly care. “

At some point, the staff ushered Mikayla into a classroom. As her parents watched from behind one-way glass, another student greeted Mikayla with a flower made of LEGO bricks.

For years, Mikayla had been withdrawn around other students. Not here. The shift was immediate. She and the other students were using tablets to play an interactive academic game, and “you could see her turn and laugh with the kids next to her,” Phil said.

Minutes later, he and Cathy were in the administrator’s office, “bawling our eyes out.”

“We said, ‘We’re all in. We have to be here. We’ll be here next week if that’s what we have to do.’”

Days later, the Watsons were at Disney World when NFSSE called. Unexpectedly, the family of a longtime student was moving. The school had an opening.

New friends, improved skills and boosted confidence

Even without the choice scholarship, the Watsons would have moved. At the same time, the scholarship was invaluable. The cost was not sustainable in the long run, Phil said, especially because he had to re-start his business.

The Watsons rented a long-term Airbnb and then an apartment before buying a house in Jacksonville. They uprooted themselves completely from Maryland, including selling their dream home.

“That was hard,” Cathy said. “You’re leaving everything you love.”

Mikayla’s turnaround, though, has made it all worthwhile.

Mikayla was reading at a first-grade level when she arrived at NFSSE; now she’s at a seventh-grade level. She loves the new graphic design class. She won an award for completing 1,000 math problems. “When she got here, she couldn’t add two plus two,” Phil said.

Her verbal skills have blossomed. She eventually told her parents something she didn’t have the ability to tell them before: In her prior school, she didn’t talk because other students laughed at her.

At NFSSE, the “kid who never spoke” speaks quite a bit.

One day, she served as “teacher for the day” in her personal economics class, delivering a lesson on how to make change.

Mikayla is kind and quick to smile. She is surrounded by friends and admirers. “Mikayla is my best friend,” said a chatty girl with pigtails who waited by her side in the hallway.

One boy held the door for Mikayla as she headed to her next class. A second hung her backpack on the back of her wheelchair. A third walked her to P.E.

Mikayla’s confidence is growing outside of school, too.

In the past, she wouldn’t say hi or order in a restaurant. But at Walmart the other day, Phil needed a card for a friend’s retirement, so Mikayla went to find a clerk. She came back and told him, “Aisle 9.”

Mikayla has a bank account and a debit card. She tracks the money she earns from chores. She routinely uses the notes app on her phone to mitigate challenges with short-term memory.

NFSSE, Cathy said, is constantly reinforcing skills and strategies to foster independence. It “pushes for potential,” just like the families do.

Mikayla “sees that potential now; she’s excited now,” she said.

Before NFSSE, the Watsons didn’t think Mikayla could live independently. Now they do.

The school and the scholarship, Phil said, have “given Mikayla an opportunity for her life that we didn’t know existed.”

He credited the state of Florida, too, for creating an education system where more schools like NFSSE can thrive.

If only every state did that.

TAMPA, Fla. — Amelia Ramos recalls her oldest child’s first school experience after moving to the Grant Park neighborhood in 2018.

“It was not a good fit,” she said. “She lasted about four months.”

In addition to academics, Ramos cited safety as a big concern.

“You couldn’t even ride a bicycle down the street,” she said.

Ramos found hope after learning about Grant Park Christian Academy, a private school affiliated with the Faith Action Ministry Alliance. The nonprofit organization’s stated mission is “to strengthen neighborhoods through meaningful engagement, collaboration, and strategic partnerships.”

Grant Park Christian Academy prides itself on its record of providing strong academics and spiritually based character development. Ramos learned from the school’s principal about a state education choice K-12 scholarship program administered by Step Up For Students that would help cover the tuition.

With that, Ramos was sold.

Her daughter thrived at Grant Park and now attends a district high school. Her son and twin daughters now attend the private school, which serves 70 students in grades K-8.

“We love the school and the staff,” she said, adding that she appreciates the assurance of knowing that her children are safe when she leaves them at Grant Park Christian Academy.

“If only they had a high school,” she said.

Although there are no plans to add a high school, an expansion will soon more than double the school's capacity, located inside a gated property owned by a non-denominational church.

The project is just one example of a broader statewide trend resulting from the Florida Legislature’s passage of HB 1 in 2023. The landmark legislation made all K-12 students eligible for education choice scholarships regardless of their household income and gave families more flexibility in how they spend their students’ funds.

Putting parents in the driver’s seat supercharged the demand for more learning options.

In the 2023-24 school year, after Gov. Ron DeSantis signed HB 1, Florida saw the largest single-year expansion of education choice scholarships in U.S. history. That growth continued in 2024-25. Recent figures from the Florida Department of Education show that more than 500,000 Florida students were using some type of education savings account.

The expansions at Grant Park Christian Academy and other schools across the state, such as Jupiter Christian School in Palm Beach County, couldn’t come at a better time. The latest figures from Step Up For Students show that the number of approved private schools has surpassed 2,500. That figure doesn’t include a la carte options, including those now being offered by public schools. State figures show 41,000 parents received scholarships in 2024-25 but never used them. According to a survey by Step Up For Students, a third of the 2,739 parents who responded said there were no available seats at the schools they wanted.

The Rev. Alfred Johnson, who founded the ministry alliance and Grant Park Christian Academy in 2014, said the school is just one of the ways the ministry works to support and improve the neighborhood. A look outside the window once a month will show teams of alliance volunteers in neon yellow vests cleaning up roadside trash. Johnson estimates that over the past three years, the group has cleared 70 tons of garbage, including old mattresses, furniture, and household appliances.

Johnson and his volunteers regularly knock on doors and survey residents and business owners about community needs. They also host events; the annual Fall Fest offers families a safe and fun alternative to Halloween trick-or-treating.

“I know what they do to really make a change in this community,” said Hillsborough County Commissioner Donna Cameron Cepeda, a Republican who represents District 5 and the county at large. She said she had known Johnson for years before she ran for office. “You can see the lives, how they have been changed because of the environment they are able to be in now.”

She was among a group of 50 community members at a recent ribbon-cutting ceremony for a new 2,660-square-foot modular building that will open after crews add the finishing touches.

Those attending the event represented a broad swath of community leaders, from local law enforcement officers to staffers at the Temple Terrace Uptown Chamber of Commerce, who brought the ceremonial oversized scissors. A representative of the Hillsborough County Clerk’s Office also attended. So did a group of leaders and students from Cristo Rey Tampa Salesian High School, which has some Grant Park Christian Academy alums.

Hillsborough County Commissioner Gwen Myers, a Democrat whose district includes Grant Park, joined her Republican colleague in praising the alliance and the school. The two commissioners also presented Johnson with a commendation honoring his contributions to the community.

“Our children are our future leaders, and when we can give them the basic foundation of education, they are going somewhere,” Myers said. “Just remember where they got their start, right here in Grant Park. What you’re doing is being a true public servant. Thank you for your vision.”

A husband, father of six, and grandfather of 12, Johnson refers to the students at Grant Park as “our babies” and describes the school as a haven of safety and peace.

“We hardly ever have any fights here,” he said. The school day starts at 7:30 a.m. After-school care is available until 5 p.m. Grant Park also offers summer camp, tutoring, mentoring and career preparation programs for the community, where the median household income stands at $32,216, and 72% of households make less than $50,000 per year. About 20% of the population did not graduate from high school. Although the area still has crime, Johnson said it has decreased over the past five years. Educational opportunities such as Grant Park Christian Academy and adult education and training play a role in improving the area’s quality of life, he said.

Johnson said he has seen many students turn their lives around. He told guests about a boy who was put outside the room for disrupting class on his first day.

“I don’t like this school,” he snarled.

“Give us a chance,” Johnson replied. He encouraged the boy to focus on his studies and respect his teachers. “You’re going to be a great leader and a great man.”

By the second year, the boy’s attitude completely changed. Test results that year showed he had the highest reading score in the school.

“That’s just one of the stories,” he said. “We have a plethora of them.”

Caleb Prewitt continued to shatter the perception of what someone with Down syndrome can’t do when he conquered the 26.2-mile course at the Bank of America Chicago Marathon on Oct. 12.

Caleb, 18, became the youngest person with Down syndrome to earn an Abbott Star for running one of the original six World Major Marathons.

The Jacksonville native, who receives a Florida education choice scholarship for students with unique abilities managed by Step Up For Students, is also recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as the youngest person with II2 (Intellectual Impairment, including those with Down syndrome) to run a half-marathon (13.1 miles). He did that when he was 16.

David, Caleb, and Karen pose near the finish line of the Bank of America Chicago Marathon. Photo courtesy of the Prewitt family

Since 2020, when he began running as a means of getting exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic, Caleb has completed 47 triathlons (swim, bike, run), five half-marathons, and now one full marathon.

(Read about Caleb’s story here.)

The marathon was his most daunting endeavor, requiring months of training. The race took its toll – he experienced leg cramps after 20 miles. Undeterred, he pressed on and continued to cheer those who lined the course and were cheering for him.

“That went on for miles and miles, and I couldn't stop him,” Karen said. “I wanted to save his energy, and he just wanted to do it. I said, ‘You know what? This is his race. He can do what he wants.’”

Those in the Florida running community who have come to know Caleb during the last five years, and the faculty and staff at the North Florida School of Special Education, which he has attended since he was 5 with the help of his scholarship, wouldn’t have expected anything less.

He is known around school as “Mr. Mayor” for his always sunny disposition, and he is a star on social media with more than 31,000 followers on Facebook and more than 45,000 on Instagram to his Caleb’s Crew pages.

Running the marathon for the National Down Syndrome Society, Caleb raised more than $2,000 for the charity. There were 40 teammates from the National Down Syndrome Society team cheering him on at various points along the course.

Caleb’s dad, David, greeted him at the finish line with a long hug and a kiss.

“So proud of you,” David told his son.

Caleb was one of 17 charity runners in the event, which meant he was featured around Chicago in ads for the marathon, and his story appeared on the race’s website.

The 17 and their families met at a reception the day before the race.

“Their stories were all great. You know, everybody's story is great,” Karen said. “It's just that I think ours is great, too.”

That prerace publicity and the fact that he and Karen wore blue shirts with “Caleb’s Crew” on the front made him stand out somewhat in the field of 54,000 competitors.

“The crowd was amazing,” Karen said. “The whole way there was support and people cheering for Caleb. Everywhere we went, they knew his name, so that was a thrill.

“It was an awesome experience. What a wonderful day.”

Jordan Glen School started in 1974 on 20 acres of woods in the small town of Archer near Gainesville. Owner Jeff Davis, a former public school teacher, moved to Florida from Michigan to start a school that allowed students more freedom. Today it continues to thrive, thanks in part to education choice scholarships. Photo by Ron Matus

ARCHER, Fla. – Archer is a crossroads community of 1,100 people 15 minutes from the college town of Gainesville, but far enough away to have its own quirky identity. It’s surrounded by live oak-studded ranch land but calling it a “farm town” doesn’t ring right. When railroads ruled the Earth, Archer was a whistle stop on the first line connecting the Atlantic to the Gulf. In the late 1800s, T. Gilbert Pearson, co-founder of the National Audubon Society, roamed the woods here as a kid, skipping school to hunt for bird eggs. A century later, rock ‘n roll icon Bo Diddley spent his golden years on the outskirts.

So, let’s just say Archer is a neat little town. And maybe it’s fitting that for half a century, it has been home to a neat little private school that doesn’t fit into any boxes, either.

Jordan Glen School got its start in 1974, when former public school teacher Jeff Davis moved down from Michigan. In the late 1960s, Davis became disillusioned with teaching in traditional schools. In his view, students were respected too little and labeled too much.

“Back in the day, I would have been labeled ADHD. I hated school,” he said. “I never met a teacher that took a personal interest in me.”

As a teacher, he saw a system that was “too constricting.”

“There was just a general distrust of children, like they were going to do something bad,” he said. Education “doesn’t have to be rammed down your throat.”

Davis migrated to what was, more or less, a “free school,” with 50 students on a farm near Detroit. Today we’d call it a microschool.

In the 1960s, hundreds of these DIY schools emerged across America, propelled by an upbeat vision of education freedom inspired by the counterculture. Davis said the Upland Hills Farm School was a free school, more or less, because while its teachers were “long-haired” and “hippie-ish,” the school had more structure and rigor than free school stereotypes would suggest.

Davis thought the Gainesville area would be a good place to start a similar school. It had a critical mass of like-minded folks. So, in 1973, he and his family bought 20 acres of woods off a dirt road in Archer. Not long afterward, they invited a little school called Lotus Land School, then operating out of a community center in Gainesville, to move to their patch in the country. Today we’d call Lotus Land a microschool, too.

It was also, more or less, a free school. Davis described the teachers and families as “love children” and “free spirits,” but in many ways, their approach to teaching and learning was mainstream. A decade later, he changed the name. “I thought people would think it was a hippie dippy school, and I knew it was more than that,” he said.

Lotus Land became Jordan Glen. The school was named after the River Jordan, after some parents and teachers suggested it, and after basketball legend Michael Jordan, because Davis was a fan.

Fast forward a few more decades, and Jordan Glen School is thriving more than ever.

It now serves more than 100 students in grades PreK-8, some of whom are the second generation to attend. Nearly all use Florida’s education choice scholarships. Actor Joaquin Phoenix is among Jordan Glen’s alums. So is CNN reporter and anchor Sara Sidner.

Jordan Glen is yet more proof that education freedom offers something for everyone and that its roots are deep and diverse. Ultimately, the expansion of learning options gives more people from all walks of life more opportunity to educate their children in line with their visions and values.

“There is something about joy and happiness that makes people uneasy and a bit insecure,” Davis wrote in a 2005 column for the local newspaper, entitled “Joyful Learning is the Most Valuable Kind.” “If children are enjoying school so much, they must not be doing enough ‘work’ there.”

“Children at our school,” he wrote, “love life.”

A peacock, one of two dozen that roam the Jordan Glen School campus, watches students at play. Photo by Ron Matus

The Jordan Glen campus includes a handful of modest buildings. It’s still graced by a dirt road and towering trees. It’s also home to two dozen, free-roaming peacocks. They’re the descendants of a pair Davis bought in 1975 because they were beautiful and would eat a lot of bugs.

Given that backdrop, it’s not surprising that many families describe Jordan Glen as “magical.”

Alexis Hamlin-Vogler prefers “whimsical.” She and her husband decided to enroll their children, Atticus, 14, and Ellie, 8, in the wake of the pandemic.

“They’re definitely outside a lot,” she said of the students. “They’re climbing trees. They’re picking oranges.” When it rained the other day, her daughter and some of the other students, already outside for a sports class, got a green light to play in it and get muddy.

Another parent, Ilia Morrows, called Jordan Glen a “little unicorn of a school.”

Like Hamlin-Vogler, Morrows enrolled her kids, 11-year-old twins Breck and Lucas, following the Covid-connected school closures. She thought they’d stay a year, then return to public school. But after a year, they didn’t want to go back. “They had a taste of freedom,” she said.

For many parents, Jordan Glen hits a sweet spot between traditional and alternative.

On the traditional side, Jordan Glen students are immersed in core academics. They take tests, including standardized tests. They get grades and report cards. They play sports like soccer and tennis, and they’re good enough at the latter to win the county’s middle school championship. Many of them move on to the area’s top academic high schools.

But Jordan Glen also does a lot differently.

Students spend a lot of time outdoors at Jordan Glen School. Activities include archery, gardening and sports. Photo by Ron Matus

The students are grouped into multi-age and multi-grade classrooms. They choose from an ever-changing menu of electives. Many of those classes are taught by teachers, but some are taught by parents (like archery, gardening, and fishing), and some by the students themselves (like soccer, dance, and book club). The youngest students also do a “forest school” class once a week.

The school also emphasizes character education.

The older students serve as mentors for the younger students. They’re taught peer mediation so they can settle disputes. Every afternoon, they clean the school, working as crew leaders with teams of younger students. Their “Senior Class Guide” stresses nothing is more important than “caring about others.”

“The way the older kids take care of the younger kids, it’s very noticeable. They are genuinely caring,” Morrows said. At Jordan Glen, “they teach community. They teach being a good human.”

“My favorite thing is that most kids really get a good sense of self and self-confidence at this school,” Hamlin-Vogler said. “Some people say, ‘Oh, that’s the hippie school.’ But the students have a lot of expectations and personal accountability put on them.”

Hamlin-Vogler said without the education choice scholarships, she and her husband wouldn’t be able to afford the school. Hamlin-Vogler is a hairdresser. Her husband is a music producer. Before Florida made every student eligible for scholarships in 2023, they missed the income eligibility threshold by $1,000. Her parents were able to assist with tuition in the short term, but that would not have been sustainable.

Her family harbors no animus toward public schools. Atticus attended them prior to Jordan Glen, and he’s likely to be at a public high school next fall. Ellie, meanwhile, thinks she might want to try the neighborhood school even though she loves Jordan Glen in every way, and Hamlin-Vogler said that would be fine.

After Ellie described how much fun she had playing in the rain, though, Hamlin-Vogler had to remind her, “You might not get to do that at another school.”

Florida gives parents the ability to direct the education of their children. Today about half of all K-12 students in the state attend a school of choice, and 500,000 students participate in state educational choice scholarship programs.

Gov. Ron DeSantis accelerated these trends in 2023, when he signed HB 1 and made every student eligible for a scholarship. No school can take any student for granted, and state funding follows students to the learning options they choose.

Unfortunately, misleading claims amplified in the media have blamed this expansion of parental choice for school districts’ budget challenges.

Sarasota County Schools, for example, recently estimated that scholarships “siphoned” $45 million from its budget, a figure cited in a WUSF article. In reality, most of the $45 million represents funding for students that Sarasota was never responsible for educating, such as those already in private schools, homeschooling or charter schools. It also does not account for students who return to district schools after using a scholarship. Once those factors are considered, the actual impact is considerably smaller than the headline number suggests.

For the 2024-25 school year, Sarasota County lost just 330 public school students to scholarship programs, but only 245 of those students came from district-run public schools. If those students had stayed, they would have brought the district about $2 million, not $45 million. That figure still does not account for the students who returned to district schools after using a scholarship the prior year, so the real impact would be smaller.

Other districts have been vocal about their budget difficulties, often attributing them solely to growing scholarship demand, such as Leon County Public Schools, which in 2024-25 lost 240 students from district-run schools (0.8% of enrollment), and Duval County Public Schools, which lost 1,237 students (1.2% of enrollment).

Statewide, 32,284 students left public schools in 2024-25 to use a scholarship. That is only 1.1% of all public-school students in Florida, and even that total includes those who previously attended charter schools, university-affiliated lab schools, virtual schools, and other public-school options.

Looking at district-run schools alone, just 24,874 new scholarship students left for scholarship programs in 2024-25. Another 5,507 came from charters, and 1,897 came from virtual schools. In fact, as a percentage of their total enrollment, charter schools lost more students to scholarship programs (1.4%) than district-run schools did (1%).

This means that the expanded scholarship program may be having a bigger impact on charter schools than districts. Charter schools, however, haven’t been as vocal about vouchers, and that is likely because charters continue to grow enrollment while district schools have started to shrink.

Enrollment declines in some districts have been real, even if the blame on scholarships is misplaced.

Declining enrollment is being driven by parent preferences – but also by shifting demographics and the ebb of the post-Covid population boom. Florida is one of the few states where overall K-12 population is expected to continue growing, but the growth will be uneven, and every school will have to compete for students.

Even as they face intense competition and demographic headwinds, Florida’s charter schools have kept growing. Some innovative district leaders have signaled a willingness to hear the demand signals from parents and create new solutions to meet their needs.

Understanding what parents seek in private and charter schools, and how new public-school models can better meet those demands, would be a good place for districts to start.

Pre-K and Voluntary Pre-Kindergarten (VPK) have also been major feeders for Florida’s scholarship programs. In 2024-25, 53,825 new scholarship students came from pre-K — somewhere between one-third and nearly half of all VPK students statewide.

Public schools have limited Pre-K offerings. Statewide, there are less than one-third as many Pre-K students as kindergartners enrolled in public schools. Private schools, by contrast, have used it as a key pipeline to recruit future students.

Districts have other avenues to respond to changing parent demands. Since 2014, when the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA) was introduced as the Personal Learning Scholarship Accounts, districts have been allowed to offer classes and services to scholarship students.

The passage of HB1 in 2023 transformed every state scholarship into an education savings account. K-12 families now have more flexibility to use scholarships for “a la carte learning,” in which they pick and choose from a variety of educational options. By offering part-time instruction, tutoring, therapy, and other services, districts can win back students and the associated funding. So far, 21 of Florida’s 67 districts have taken advantage of this opportunity, with 10 more in the pipeline.

Florida’s enrollment shifts are real, but data shows the “voucher drain” narrative overstates the impact. The real challenge for districts is not money being “siphoned;” it is families choosing other options. Districts that adapt and compete for students will keep both enrollment and funding – leaving students, families and taxpayers better off.

Markala was Marlena and John Roland’s first child, and there were more on the way – four more, in all. And Markala was 5, so the Roland children were going to reach school age in quick succession.

This presented a dilemma.

“We wanted our kids in private school, but we didn’t have the money,” Marlena said.

But there was hope.

The year was 2005, and Marlena, a teacher at a private school near their Coral Springs home at the time, learned about a private school scholarship that had been established a few years earlier and was managed by Step Up For Students.

For nearly 20 years, a member of the Roland family attended a private school with the help of a scholarship managed by Step Up For Students.

She applied and was accepted, and for nearly all of the next 20 years, at least one of the Roland children attended a private school with the help of a Step Up scholarship. The exception was the two years the family lived in Georgia.

“It was a blessing for us,” John said. “The best thing we did was give them that education foundation.”

“None of that would have been possible without the scholarship,” Markala said.

Marlena was a teacher at ALCA when the kids began school. Even with the employee discount, she said the cost of tuition would strain the family’s finances. Still, she wanted her children to benefit from ALCA’s educational setting just like the students she was teaching.

“We wanted to set the bar high, to create good study skills and habits. We wanted them to be well-rounded,” said Marlena, who also taught at The Randazzo School for nearly 10 years, including the time Marcia attended.

Marcia, who graduated last May from The Randazzo School, was the last of the Roland children to use a scholarship managed by Step Up For Students.

It was by design that the Roland children split their education between private and district schools. Some were sports-related, but mostly, John wanted their children to experience both educational settings.

“John said, ‘Let’s put them in public school for a little bit and see how it goes,’” Marlena said. “He said they need to have both, and that will build character and build them as individuals.”

And it worked.

The private school experience helped the children excel at their district schools.

“It laid a really good foundation for us,” Markala said. “Just getting us excited to be in the classroom, to learn new things, to collaborate with others.

“I had friends (in high school) ask me, ‘Where did you learn this? Why are you thinking that way?’ All I could say was, ‘Thanks to my teachers at ALCA and Westminster.’ They really set us apart and prepared us for what was coming next. We were leaps and bounds ahead of our peers.”

John credited the private school education his children received but also gave credit to the emphasis he and Marlena placed on education at home.

“When I dropped them off at school, I told them we’ll add to it when you get home,” he said.

“They didn’t play with that,” Markala said. “That was non-negotiable in our house.”

She remembers a time when John sold the family pickup truck to help meet the expenses of her attending Westminster that the scholarship didn’t cover.

“As a kid, you see them doing that, and I'm like, ‘Don't we need that car to get places?’ They really valued education. That was what was important,” she said. “I see that now as an adult, the things that they're willing to do to make sure that we had a good education, putting us into spaces where we could learn and grow have been tremendous to me, even now that I’m in the workforce.”

Last week, I had the opportunity to make a presentation about how lawmakers can support teachers who want to start their own schools. The four key features:

2. Formula funding/demand-driven funding: Whoever applies for a choice program should receive funding if eligible.

3. Avoidance of anti-competitive accreditation requirements: Don’t ask your startup schools to operate without funding from the choice program while incumbent/accredited schools receive choice funding.

4. Exempt private schools from municipal zoning: Old hat for charter schools, needed for private schools as well.

Florida is the only state your humble author is aware of that has taken all four of these steps. This makes Ron Matus’ new study "Going With Plan B” all the more important. Despite a statewide increase of 705 private schools, 41,000 Florida families applied for, received, and ultimately did not use an ESA. Matus surveyed thousands of these parents to learn why.

The lack of school space was the No. 1 reason Florida families found themselves as non-participants. Reasons two and three were related to costs, which can also be thought of as a supply issue.

The “Going with Plan B” study is very interesting and should be studied carefully by Florida policymakers. For now, however, let us focus on the other states with choice programs that lack the four critical elements listed above. If FLORIDA has a supply issue, your state, sitting at one out of four, or two out of four, should take note: It is likely to be even worse in a state near you.

It's hard to find an athlete as exuberant as Caleb, who celebrates at the finish line of each of his races with a choreographed dance and high-fives for everyone. (Photo provided by the Prewitt family)

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. – David Prewitt was worried.

His wife, Karen, wasn’t.

“He can do it,” she said.

Their son Caleb, 13 at the time, was participating in his first open-water swim, something he needed to conquer if he was going to complete his first triathlon.

One thing you need to know about Caleb: He has Down syndrome.

Another thing you need to know about Caleb: It has never held him back.

“When we came home (from the hospital) with Caleb, we said he’s not going to be your typical young man with Down syndrome. We’re going to push him, and so we've always tried to raise him as a typical child,” Karen said.

That meant chores around the house, being active in sports, attending school, and making friends inside and outside of the Down syndrome community.

“We kind of upped the ante when we got into sports,” Karen said.

She coaxed Caleb into running a 5K on Thanksgiving of 2020 by using the Couch to 5K app that gradually built up his endurance. Now, Caleb was training for a triathlon – a 300-meter open-water swim, a 12-mile bike ride, and a 5K race.

He had learned to ride a bike. He had swum in a pool plenty of times. But what concerned David was that Caleb, with assistance from a volunteer partner, was now swimming in a lake to see if he had the strength and stamina to finish that leg of the race.

Turns out, he did.

“He comes out of that water, and he's just laughing,” David said. “And I thought to myself, ‘You’ve got to change your attitude,’ because this kid can do things.”

***

Caleb is now 18. He has completed 119 races in the past five years. Included are 44 triathlons of various distances, five half-marathons, and two Spartan Races.

The Guinness Book of World Records recognizes Caleb, 16 at the time, as the youngest person with II2 (Intellectual Impairment, including those with Down syndrome) to run a half marathon (13.1 miles). Caleb’s goal is to add his name to that book again in October by becoming the youngest person with II2 to run a marathon (26.2 miles) when he and his mom run the Chicago Marathon.

Stephen Wright was Caleb’s partner during the early part of Caleb’s running career. He’s amazed at all Caleb has accomplished.

“I don't think people realize, most 14- 15-, 16-year-old kids aren't doing that,” he said. “So not only does he have things he's trying to overcome and prove he can do things, but most kids his age aren't doing the things he's doing. It’s incredible, because I wasn't doing that stuff at his age.”

***

Deb Rains is the assistant head of school at the North Florida School of Special Education (NFSSE) in Jacksonville, where Caleb attends on a Unique Abilities Scholarship managed by Step Up For Students.

Rains called Caleb the school’s “Mr. Mayor.”

“He’s so outgoing,” she said. “He’s friends with everybody.”

Rains said Caleb’s always-in-a-good-mood personality and can-do spirit come from the support he receives from Karen and David. More than a decade later, she vividly recalls her first meeting with them when they visited NFSSE to see about enrolling Caleb.

“I will never forget this. They came in and they had his mission statement,” Rains said.

It read:

“We built everything around that,” Karen said.

It is important to the Prewitts that Caleb has friends outside of school because, as is often the case when students graduate, friends from school scatter to live their own lives.

Caleb has friends from school. Luke, a classmate, is his best buddy. But Caleb has friends outside of school, too. He belongs to four running clubs. He has friends from Planet Fitness, where he works out, and friends from Happy Brew, a Jacksonville coffee house that sells Caleb’s homemade cookies. (More on that shortly.)

They want Caleb to have a job and be self-sufficient. He graduated in May from NFSSE and will enter the school’s transition program, where he will learn employment skills.

“We're very thankful for that,” David said. “He's got a lot of things that he can look forward to, because he's pretty well known in the community.”

Caleb is eager to hit the job market. He’d like to work at Happy Brew, Planet Fitness, or Publix. David, now retired, worked as a store manager for Publix. Caleb’s sister, Courtney Tyler, works in a Publix bakery.

He’s getting a jump this summer on a possible job at Happy Brew by attending NFSSE’s barista camp.

“As an organization, you have a mission statement and a vision statement, but to take that and place that intentionality on their son's life just showed me that they were not limiting him because of his disability,” Rains said.

“I was very impressed by that. There was a statement to not just me, the school, but to the community, that they expected nothing less from their son than they would their daughter, who's neurotypical.

“That just created the path for him. Since they didn't put any boundaries or limitations on Caleb, there was none for him to be impacted by.”

***

The mood surrounding a child born with Down syndrome isn’t positive, David said. Parents are informed of all the things their child won’t be able to do – ride a bike, run, swim, get a job.

“We were on a mission to prove them all wrong,” Karen said.

Along the way, Caleb has become a role model for the Down syndrome community. He has advocated at the state capital in Tallahassee for the expansion of what is now the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities, which he receives. Karen has written newspaper op-ed columns and spoken to legislative committees in Tallahassee in support of the scholarship.

“If we didn’t have the scholarship, we would have had a tougher journey,” she said.

Caleb has more than 26,000 followers on Facebook and more than 44,000 followers on Instagram. Karen said parents comment on the posts, saying they have more confidence in their child’s abilities after seeing what Caleb has achieved.

Caleb has appeared on NBC’s “Today” show during a segment featuring children with unique abilities who cook or bake. Caleb bakes. Currently, he’s baking the cookies sold at Happy Brew.

It started during the COVID-19 pandemic when Caleb began helping his dad in the kitchen. That led to their cooking show, “Fridays at Four,” that were posted to Facebook. They were hugely popular.

Now, Caleb bakes 20 dozen chocolate chip and sugar cookies a month and delivers them to Happy Brew. The sugar cookies are a hit.

“We can’t keep them on the shelf,” owner Amy Franks said.

Caleb’s “Mr. Mayor” personality is in full force when he visits the coffee shop, Franks said.

“He'll walk in, he'll immediately step behind the counter and start making a smoothie, or he'll hop on the point of sale, like he owns the place, and we just let him do his thing, like go for it,” Franks said. “His work ethic is incredible. He never stops.”

Caleb often wears a T-shirt bearing the slogan, “No Limits.” He wrote that on top of his mortarboard at graduation.

Running, cooking, working out at the gym, Caleb has yet to encounter a limit.

And he does it all with a smile.

“The joy inside of him is so meaningful for us,” Franks said.

***

In 2021, Stephen Wright volunteered to be a partner for a special needs athlete and was paired with Caleb for a triathlon in Sebring.

He remembers how excited Caleb was before the race, and how concerned he was about how Caleb would react to the competition, the crowd, the long swim, which is the first leg.

“There was one point (during the swim) where I turned around and he wasn't there, and I started panicking,” Wright said. “He was actually underwater, trying to tickle my feet. And I was like, ‘All right, man, I can see how the rest of this day is going to go.’ We got out of the water, and everyone cheered for him.”

The two were dead last when they transitioned from the bike ride to the run. At one point, Wright couldn’t see any other runners. He wondered if the race was over.

What he didn’t know was that at the finish line, the race director was rounding up the younger runners who were waiting for the awards presentation and told them to go to the finish line and cheer on this young man who was running his first triathlon.

David and Karen were among those waiting for Caleb.

“That finish line,” Karen said, “was one of the best experiences of my life.”