Editor's note: With this commentary, redefinED welcomes education policy expert Lindsey Burke, director of the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation, as our newest guest blogger.

Editor's note: With this commentary, redefinED welcomes education policy expert Lindsey Burke, director of the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation, as our newest guest blogger.

Education policy scholars, especially proponents of school choice, have long referenced the late Clayton Christensen’s work on disruptive innovation. Christensen, along with his colleague Joseph Bower, detailed the concept of disruptive innovation in the Harvard Business Review in 1995.

The idea of “disruption” in a sector “describes a process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses,” wrote Christensen, Michael Raynor, and Rory McDonald in 2015 in a follow-up Harvard Business Review article refining the theory.

Disruptive innovation theory posits that dominant incumbent businesses may ignore a segment of their consumer base as they focus on improving products for their most profitable customers. Scrappy new market entrants then target neglected customers with early, cheaper versions of their product, and then begin growing market share as the product improves. The new business then begins capturing more customers, improving product performance while maintaining affordability, and eventually becomes mainstream.

Christensen and his colleagues caution against over-application of the theory to phenomena that do not actually represent disruptive innovation, but rather sector transformation. For example, they note that Uber, despite its incredible impact on the taxicab industry, represents sector transformation rather than disruption in part because of Uber’s large market share. This is also the case because Uber wasn’t competing with the absence of a vehicle transportation market, just a crummy one.

To be appropriately described as “disruptive,” a new entrant into the market must be enabled by one of two conditions: 1) “low-end footholds” or 2) “new-market footholds.” “Low-end footholds” emerge when existing businesses ignore “less-demanding” customers because they are overly focused on their more “profitable and demanding” customers. “New-market footholds” emerge when there isn’t a market for a good or service, turning “nonconsumers into consumers.”

As Christensen and his colleagues explain, the bottom line is this: Genuine disruption happens by market entrants “appealing to low-end or unserved consumers” and then capturing the “mainstream” market.

So, does the new phenomenon of pandemic pods unfolding across the country qualify as disruptive innovation in the K-12 space?

They certainly check some of the initial boxes.

Pods are a “new-market foothold” competing with non-consumption. Pandemic pods arose this summer after the widespread school shutdowns that occurred during the spring showed no sign of stopping. Parents, concerned about the prospects for their children’s education this fall, began teaming up with other families in their neighborhoods or social circles to hire teachers for their children. Some families unenrolled their children from their district school completely, registering in their state as homeschoolers and then joining a pod.

With pods, families work together to recruit teachers that they pay out-of-pocket to teach small groups — “pods” — of children. It’s a way for clusters of students to receive professional instruction for several hours each day. Families pool resources to pay tutors who may serve as a full-time teacher for the pod of students or may only teach on a part-time basis.

With many school districts around the country planning not to reopen classrooms this fall — or, at best, planning to offer some combination of virtual and in-class instruction — pods are competing with non-consumption, establishing themselves through a “new-market foothold.”

But time will tell whether pods remain a permanent facet of the education landscape. Disruptive innovation theory also holds that “innovations don’t catch on with mainstream customers until quality catches up to their standards.” Rather than making improvements to existing products in a market (such as increasing the computing power of a laptop or the cooking consistency of a microwave), disruptive innovations are “initially considered inferior by most of the incumbent’s customers.”

So, here’s where the ground is a little shakier for pods as a disruptive innovation. According to Christensen’s work on the subject, disruption also has a second qualifying condition: The new product must be inferior to the product offered by the incumbent.

Parents may consider some, but not all, of the components of a pod inferior to the existing education model. They may find the academics to be more rigorous, but the custodial component less competitive if it doesn’t provide the same length of coverage. Pods also are on shakier ground vis-à-vis disruption because some families join as a supplement to the crisis online instruction their children are still receiving through their district school. In that way, they could end up complementing the incumbent rather than disrupting it.

A third marker of disruption: The eventual improvement of quality. But there are already promising developments in the realm of pod quality. Education researcher and redefinED executive editor Matthew Ladner describes what a marriage between pods and established charter incumbents like Success Academy could entail. As Ladner explains, taking the Success Academy (COVID-era) model of "most skilled math instructor in the network [giving] live internet broadcast lectures" and coupling that with teachers and tutors working in small pods across the country to assess student learning and provide individual instruction could lead to high-quality pods at scale.

Finally, to truly qualify as a disruption, pods also will have to eventually serve a broad segment of the K-12 market. This will only happen through policy changes that can enable widespread participation in the model on the part of lower-income consumers.

For parents who cannot afford to pay out-of-pocket to contribute to a neighborhood pod, providing resources through education savings accounts (ESAs) will be a crucial support moving forward. With an ESA, currently available in Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee, and North Carolina, eligible families whose children exit the public education system can receive approximately 90% of what the state would have spent on that child in her public school directly into their ESA. These restricted-use, parent-controlled accounts can then be used to pay for any education-related service, product, or provider of choice, including private school tuition, special education services and therapies, online learning, and private tutors.

Unused funds can even be rolled over from year to year. They enable families to completely customize their child’s education and are the perfect education financing policy to support families of all economic levels enrolling their children in pods. The pandemic has made it clearer than ever that every state needs to provide education choice – ideally through an ESA model – to all children, yesterday.

Universal ESAs would enable pods to serve a broad segment of the K-12 market, competing with, and potentially disrupting, the district school model.

Currently, district schools are mostly closed to in-person instruction, creating a clear case of non-consumption with which pods can compete. But even when the public education “product” is on the market as usual, it’s not a product that is serving consumers particularly well. Just one-third of students across the country can read and do math proficiently, and in some of the largest school districts in the country, like Detroit, those figures fall into the single digits.

Just as the pandemic is reshaping so many aspects of our lives, it also is reshaping education. Although the extent to which this transformation is permanent is yet to be seen, some non-trivial percentage of families is likely to continue their children’s education in something other than a district public school even when the pandemic subsides.

Pods could be what they choose. Pods are a “new-market foothold” that are competing with non-consumption (closed public schools), and could, at present, be considered an “inferior” product. But that will change as families and service providers refine the pod product. At that point, coupled with changes to policy providing ESAs to as many students as possible, they could fundamentally change the education marketplace.

As such, pods are a strong contender for what could be disruptive innovation in the K-12 space.

Graduate training in the social sciences teaches students to think in terms of a multi-variable world. Humans naturally gravitate toward simple explanations of reality, such as X caused Y, when in fact isolating the impact of X on Y with reliability is very difficult.

Graduate training in the social sciences teaches students to think in terms of a multi-variable world. Humans naturally gravitate toward simple explanations of reality, such as X caused Y, when in fact isolating the impact of X on Y with reliability is very difficult.

Random assignment studies are the most useful in this regard, but these sorts of studies are difficult and expensive to arrange, and many policies do not lend themselves to random assignment. Many times, we have little choice but to make decisions based upon lesser evidence.

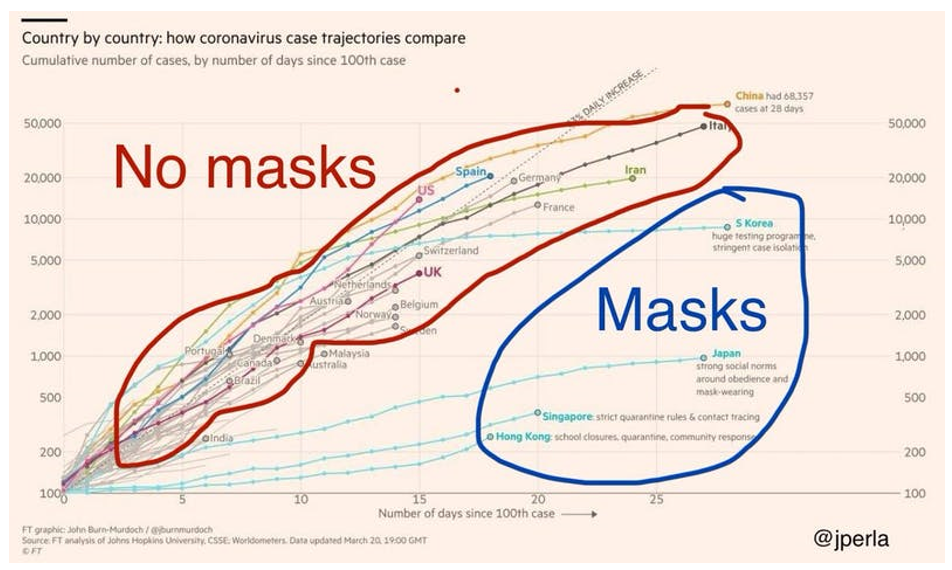

The social scientist is trained to look at technology leader Joseph Perla’s chart above and say, “We shouldn’t assume that South Korea, Japan and Singapore are having a good pandemic because of masks. It could be something else, or it could be multiple other factors. Masks could actually be bad.”

This is all potentially true. Moreover, unless you are willing to randomly assign people to wear masks in public and prevent the control group from wearing them, you cannot know for sure.

Policymakers, on the other hand, do not have the luxury of epistemological nihilism. They must make decisions, almost always based upon incomplete or otherwise imperfect information.

President Harry Truman once said: “Give me a one-handed economist. All my economists say, 'on hand...', then 'but on the other ... ’”

So, while the social scientist looks at this chart and suspects foul play, the pragmatist looks at it and says, “Well, there could be other things going on, and masks could still be playing a positive role.”

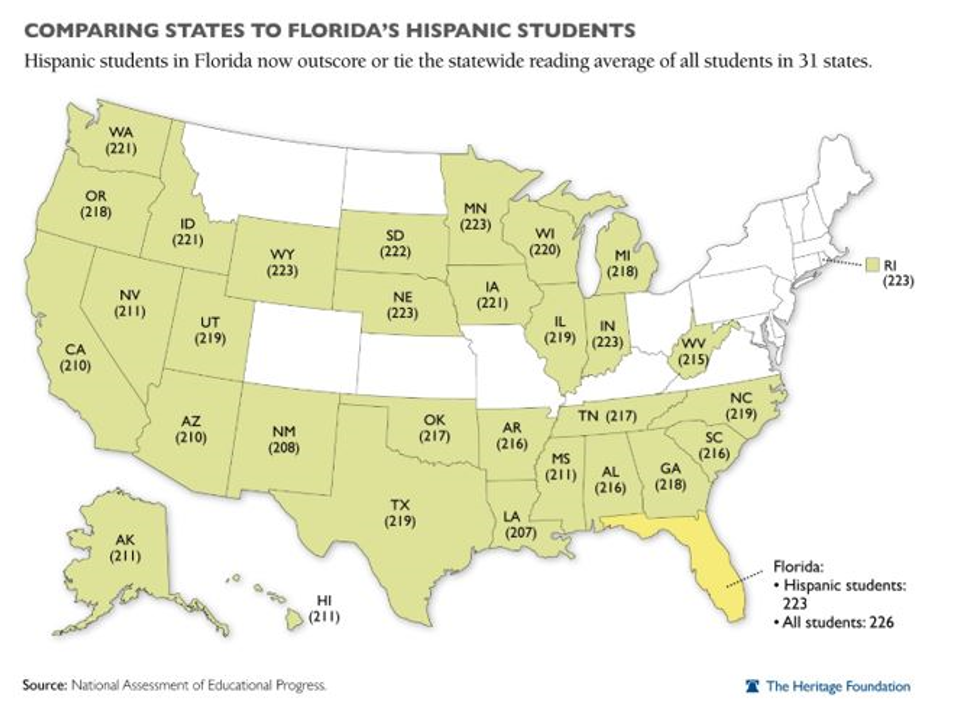

K-12 policy also gets made in a chaotic world with multiple policy changes occurring at the same time. Back when I collaborated with the Heritage Foundation to produce the map below comparing the fourth-grade NAEP scores of Hispanic students in Florida to the statewide averages for students across the country, critics raised the social science objection: “You don’t know which Florida policy led to the increase,” was the essence of the complaint.

This was entirely correct from the point of view of the social scientist, but the pragmatist in me required me to say: “Since we don’t know which of the many reforms in the Florida cocktail led to the improvement, don’t take any chances – implement all of them.”

Likewise, someone might want to study everything Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore have done to prevent the spread of COVID-19. It is not necessarily the same approach. But right about now, encouraging people to wear masks in public is looking like a pretty good idea, not dissimilar from studying a state whose minority students score a grade level higher than your statewide average on reading.

Many conservatives and libertarians question whether the federal government should get involved in school choice.

They might believe in scholarship or voucher programs, but they also believe the federal government shouldn't create them, except in certain narrow cases. Those include programs for students in Washington D.C., where Congress oversees the education system, students living on Indian reservations, and a few others.

A new Heritage Foundation report argues the federal government could fund educational choice for another group of students — those whose parents serve in the military.

The report argues:

The federal government’s exclusive responsibility and mandate to oversee national defense and the military extends to military-related issues that impact education. Whereas education is not an enumerated power of the federal government per the U.S. Constitution, national defense is clearly so, and the education of military-connected children has a special place as a Department of Education (DOE) program. Since it pertains to the U.S. military Impact Aid is one of the few federal programs dealing with education that has constitutional warrant. Just as there is no question, constitutionally speaking, that the federal government has authority over the military, so also does the federal government have authority to implement or modify programs that provide federal funding to military families.

The conservatives at Heritage don't want new federal spending. Their basic idea is straightforward. Rather than send federal "Impact Aid" to school districts in the vicinity of military bases, the federal government could give control of the money directly to families. Parents could place the money in education savings account that could pay for private school tuition, homeschooling expenses, or related uses.

It's an intriguing idea. And it's triggered a debate that gives lie to one of the great false dichotomies in education policy: Funding students, versus funding the system.

'Bonkers?'

Andrew Rotherham of Bellwether Education Partners calls the Heritage idea "bonkers." He and other critics say Impact Aid is supposed to compensate school districts for giant, federally owned military properties that take huge chunks of land off local property tax rolls. Giving the money directly to families would run afoul of that purpose. Hilary Goldmann, executive director of the National Association of Federally Impacted Schools, told the Washington Post Impact Aid is supposed to “serve all the children in the district — not a certain subset.” (more…)

The cover story in this spring’s Philanthropy magazine opens with redefinED host John Kirtley walking beside a civil rights legend at the front of a record-setting 2010 school choice rally that urged Florida lawmakers to expand Tax Credit Scholarships for low-income students. It then drops backs a dozen years to trace his efforts at helping poor schoolchildren and, in the process, provides considerable detail about how and why he entered the arena of political action committees and campaign contributions.

The magazine is published by the Philanthropy Roundtable, which is directed by former Heritage Foundation educational affairs vice president Adam Meyerson, and the article certainly takes for granted that the public education system needs a profound push to get students back on track. But this story includes a variety of political and philanthropic voices, all of whom insist the charitable model for education reform must now apply business principles similar to those instituted by Kirtley and, more pointedly, be committed to stepping into the political arena to counter the powerful influences of teacher unions.

Those voices include New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who tells Philanthropy: “We have an obligation to stand up for our children, for their lives, their futures, their hopes and dreams. And that means putting their needs first.”

by Robert Enlow

States’ relationship with the federal government in education is like Gollum’s connection with the One Ring in “The Lord of the Rings”: They loves it, and they hates it. States either can “abide with the great pain” and continue with stagnating outcomes, or they can free themselves, their educators, and their families and achieve better academic results.

In 1966, through the adoption of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the federal government provided $2 billion for public education (using 2006 dollars). In 2005, that number increased to $25 billion. In 2010, total federal spending on K-12 education reached $47 billion. And in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act alone, the feds dedicated $100 billion to public education.

This “free” money is what the states love. Who doesn’t love free stuff? But, as Milton Friedman so wisely said, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. With those federal funds come regulations on educators, debt for future generations and significant questions of whether those federal funds are spent on effective programs.

First, the regulations, which states and localities really hate: In 2007, Dan Lips and Evan Feinberg reported that although the federal government provided just 7 percent of overall funding for public education, it was responsible for 41 percent of the administrative burden placed on states. Those regulations inhibit educators, especially rural ones in small schools, from doing their jobs effectively. And they inhibit the ability of state education departments to be as effective and efficient as possible. According to the Heritage Foundation:

“After the passage of No Child Left Behind (an update to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act), several states released calculations comparing the administrative cost of compliance to the amount of federal money they receive under the law. In 2005, the Connecticut State Department of Education found, for example, that Connecticut received $70.6 million through Title I of NCLB but had to spend $112.2 million in implementation and administrative costs.”

The federal government’s involvement in education also is placing a burden on the unborn. The United States is broke! It is nearly $16 trillion in debt. Federal education funds expended to states are borrowed. That, along with the federal government’s other “investments,” is unsustainable and must be curbed. (more…)