A few weeks ago, Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona had this to say at a national education conference sponsored by Latinos for Education:

A few weeks ago, Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona had this to say at a national education conference sponsored by Latinos for Education:

“We’ve often heard and maybe even explained that education is the great equalizer. Well, now’s our chance to prove it. Funding is there. Urgency from the president is there. Are we going to lead through this and come out stronger? I say we can.”

Cardona pointed out that the American Rescue Plan, President Joe Biden's first pandemic relief plan, included $130 billion for K-12 education and $40 billion for higher education. However, none of this funding was allocated to give families direct support when searching for access to school options to non-government schools.

Further, not all the funding meant to help these non-government schools has been received, despite how critically it’s needed.

During the same education conference, Hispanic leaders urged the Biden administration to give Hispanics a seat at the table. Those leaders expressed that Hispanic students make up more than a quarter of the nation's public school students but still are not fairly represented by teachers at public schools, nor are they getting a fair shot at access to education.

This lack of access spans from early learning opportunities to limited support to access to a college, according to this Latinos for Education report.

While the pandemic has had a great impact on all American children, it has affected communities of color and low-income students at a higher rate, especially Hispanic students, and has widened learning gaps even further. These students have faced many challenges, from lack of internet or electronic devices to language and computer literacy barriers as families struggled to help students at home.

It’s fair to say these challenges have been greater for Hispanic students than white students; it is not fair to say that students of color are hurting just because of the pandemic; they have been hurting for a long time. The hurt has been ongoing for generations. Low-income students of color have been continually impacted by the lack of school options in the U.S. and by a ZIP code system that was created to fail them.

Before the pandemic's turmoil and disruption, only around 35% of fourth-graders in the United States scored at the competency level in reading. Broken down by race, 45% of white children scored at competency level compared with 18% of Black students and 23% of Hispanic students overall.

Cardona, who is Hispanic himself, said we have a chance to help Hispanic students now. He can use his voice to truly represent Hispanic communities that are desperately asking for more school options and a shot at a great education.

He has the power to create an education system that empowers every parent and student to be the drivers in choosing what is best for them. Simply allocating funding to public schools is not enough; it’s time to reimagine education in the United States.

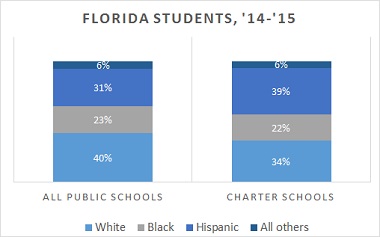

Over the past five years, the number of Hispanic students in Florida's public schools has swelled by more than 150,000. Those students appear to be disproportionately moving to charter schools, where the Hispanic enrollment has grown by nearly 50,000, more than doubling since 2010.

Children play outside at Immokalee Community School, one of a growing number of charter schools where the majority of students are Hispanic.

Hispanics now represent the single-largest ethnic group in Florida's charter schools, accounting for 39 percent of their students during the 2014-15 school year.

In Miami-Dade County, the state's largest school district, 79 percent of charter-school students are Hispanic, compared to roughly 68 percent of all public-school students. The trend holds in Osceola County, the state's other majority-Hispanic school district, and also in Broward, the second-largest district in the state.

Hispanics in Florida are far from a monolithic group. Julio Fuentes, the president of the of the Hispanic Council for Reform and Educational Options, said the label masks diverse cultures — from predominantly Cuban-American Miami-Dade to heavily Puerto Rican areas in Central Florida.

"Probably the one issue that brings us the closest together is education," Fuentes said. In multiple surveys, by his group and others, "the common denominator among the Latino community is access to a quality education." That, he added, may help explain why parents are more likely to seek out different schools — including charters — for their children. (Fuentes also sits on the board of Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog and employs the author of this post).

For Andrea Velez, the decision to enroll her daughter in a charter school began with the desire to find a school that would challenge her academically. Private school was not an option.

She ultimately settled on Choices in Learning in Seminole County. She said she was impressed by its use of the Success for All reading curriculum and "cooperative" approach to learning.

"Ultimately what it really came down to was, where was I going to send my daughter that she could thrive?" Velez said. "I wanted her to have the best opportunity that I could provide her with."

Now her daughter has moved on to middle school, and Velez has chosen district-run magnet program focused on engineering, where she can pursue her interest in science. (more…)

Editor's note: This is the third post in our series commemorating the 50th anniversary of Dr. King's Dream speech.

It was January 18th, the Saturday of the MLK weekend in 1997, when I printed out the “I Have a Dream” speech. I’m not completely sure why, except that I was transitioning in my life from international business to education reform. The powerful language and ideas King conveyed, especially the notion that we had defaulted on our promissory note, captured me then and have stayed with me. The speech has been in my briefcase ever since. Multiple times each year, I pull it out when I need to refresh my memory as to why I remain engaged in what is often such an arduous struggle.

By now, I hope, people are familiar with the dismal stats. Our schools remain mostly separate and unequal. Schools that enroll 90 percent or more non-white students spend $733 less per pupil per year than schools that enroll 90 percent or more white students. That’s enough to pay the salary of 12 additional new teachers or nine veteran teachers in an average high-minority school with 600 students. Almost 40 percent of black and Hispanic students attend those high minority schools, whereas the average white student is in a school that’s 77 percent white. Whites now constitute only 52 percent of K-12 demographics.

Meanwhile, only 19 percent of Hispanic 4th graders and 16 percent of black 4th graders scored proficient or above on the 2011 NAEP reading exam. About half of Hispanic and black students were “below basic,” the lowest category. Even our best students often leave the K-12 system unprepared, as best evidenced by a 60 percent remediation rate in the first year of college and large numbers of dropouts.

Although progress has been made, America remains in default on its promise of access to a high quality educational experience for all. In the words of Dr. King, we are addicted to the “tranquilizing drug of gradualism,” and mired in a “quicksand of racial (as well as class) injustice.” Powerful adult interest groups continue to benefit. That part is analogous to the civil rights struggle of the 50’s and 60’s, though thankfully so far without the snarling dogs, fire hoses and bullets. My frustration with the pace is that the vision of justice, of what is right and what is possible, is so clear. We see hundreds of charter schools, private schools and traditional public schools achieving at high levels with children of all classes and ethnicities. When we know better, as we do, we should do better. But mostly we do not.

Parental school choice alone is no panacea. Standards need to be raised; teacher recruitment, preparation, training, evaluation, and compensation systems dramatically restructured; and technology integrated to improve efficiency. But Dr. King would likely look askance at using school district attendance boundaries to corral families the way we do cattle, allowing them in and out only when it pleases the owner. This system is inherently unjust, immoral, and even evil when it condemns families to poor performing schools year after year, generation after generation. It forcibly segregates us from one another. Without choice, we de facto have Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate, but equal” that has never actually been equal. Often it destroys hope. (more…)

Editor's note: This is the second in our series of posts commemorating the 50th anniversary of Dr. King's "I Have a Dream" speech. Darrell Allison is president of Parents for Educational Freedom in North Carolina.

Is school choice the civil rights issue for the 21st Century? I say it’s always been an issue.

While the battles, faces, and nuances have changed, we are still wrestling with core questions of equality, education as a means of opportunity, and creating a just society.

On Feb. 1, 1960, four young men from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, Ezell Blair, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, and David Richmond, were refused service at a lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C. because of the color of their skin. In response, they turned the nation’s attention to injustice and inequality by remaining in their seats until closing time. The sit-in continued the following day; pretty soon, after significant media attention, sit-ins were happening elsewhere in North Carolina and in cities across the South.

In 2013, four courageous young men followed in their footsteps by bringing attention to educational injustice to the North Carolina legislature. Reps. Marcus Brandon and Ed Hanes (both Democrats), and Brian Brown and Rob Bryan (both Republicans), each took political hits and overcame harsh rhetoric as they jointly sponsored The Opportunity Scholarship Act.

Opportunity Scholarships give students from low-income and working-class families the ability to attend non-public schools that could better meet their needs. The hard reality is, not much has changed since the 1960s when it comes to educational choices. Wealthy parents have always had access to an array of options that many lower-income, mostly minority students do not. This was the justification behind Opportunity Scholarships - to provide the same equality of choice to poor families.

As Dr. King once said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere … whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” In North Carolina, we have a 30 percentage point achievement gap between non-poor and economically disadvantaged students, a 30 point gap between whites and blacks, and a 24 point gap between whites and Hispanics. If we treat Dr. King’s quote as truth and not a catchy saying, where is the moral outrage?

These statistics reveal a great divide – one that Brown v. Board of Education sought to address in 1954. The landmark case recognized segregation in public education was wrong. However, I contend that Brown v. Board was not simply and narrowly about placing black kids in classrooms with white kids. It was, at its very core, a school choice issue because one of its underlying premises was the quality of education was not the same for minority students compared to their white counterparts. (more…)

Merrifield: More school choice could make a teacher's job less Herculean. (Image from teacherportal.com)

Editor's note: John Merrifield is an economics professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio whose primary academic interest is school system reform studies. He's also editor of the Journal of School Choice, initiator of the annual School Choice and Reform International Academic Conference, and author of the critically acclaimed "The School Choice Wars."

A recent Wall Street Journal article about a National Council on Teacher Quality report on widespread deficiencies in teacher training programs is the latest example of hand-wringing about teacher ineffectiveness. Without discounting completely the need to address this issue along with others in the teaching profession – such as low pay, tenure, high turnover, poor materials, and the tendency to draw the lowest ability students - allow me to suggest the root of our teaching skill problem is actually the public school system’s monopoly on public funding.

The current system generates classroom composition that is so heterogeneous in student ability and life experience that only an extraordinarily rare teaching talent achieves significant academic progress for a high percentage of students in public school classrooms. Policies like mainstreaming a lot of special needs children will make teacher and public luck, in the form of unusually homogenous classrooms, increasingly rare.

Data reveal a few schools at the top and bottom that perform well or poorly with all students, respectively. But the truth is, teachers are quite effective with certain students and not effective with others - something that is often concealed by comprehensive test score averages. In 2011, I analyzed this fact in Texas, which has test score data disaggregated into several student sub-groups, and is especially important in Texas because of its diversity: large black and Hispanic populations and considerable variation in urban and rural settings. We found schools that taught black students well, and Hispanic students poorly, and vice versa. Other schools did well with low-achieving students, but not well with high achieving students, and vice versa.

Many would like to believe schools do an equally good job, regardless of race, ethnic background, students’ average ability level, or socio-economic status. Sadly this is not the case, and the differences are significant. Each school typically does better than others with different groups because teachers have strengths and weaknesses, even when they are not hired for them. (more…)

Florida’s high school graduation rate rocketed 23 percentage points to 72.9 percent between 2000 and 2010, putting the Sunshine State at No. 2 among states for progress over that span but still behind the national average, according to a new national report.

Only Tennessee did better, with a 31.5 percentage point gain, shows the annual Diplomas Count report from Education Week. The national rate was up 7.9 percent, to 74.7 percent.

Education Week, the country’s highly respected paper of record for education news, uses its own formula to calculate graduation rates.

Its findings are the latest in a stack from credible, independent sources that show Florida students and teachers are making some of the biggest academic gains in the country under a model distinguished by a tough, top-down accountability system and expanded parental school choice.

Florida ranks No. 44 in the percentage of students eligible for free- and reduced-price lunch (with the ranking going from lowest rate to highest), according to the latest federal figures. But the Education Week data puts it at No. 34 in graduation rates, ahead of states with less challenging student populations - and arguably better academic reputations - like Washington, North Carolina and Utah.

The gains also come despite tougher standards than other states. Among other things, Florida requires more academic credits to graduate than most states (24 to the national average of 21.1) and the passing of an exit exam (only 23 other states do). (more…)

Kristopher Pappas, a sixth-grader at Orlando Science School, looks like a lot of 11-year-olds, like he could have a Kindle and a Razor and put a little brother in a headlock. But Kristopher says he wants to be a quantum mechanic, and with a blow dryer and ping pong ball, he proves he’s not an idle dreamer. He turns on the blow dryer and settles the ball atop the little rumble of air stream, where, instead of whooshing away, it shimmies and floats a few inches above the barrel. The trick is cool, but it’s Kristopher’s explanation that fries synapses. “You got to give Bernoulli credit,” he begins.

Bernoulli?

As a whole, Florida students don’t do well in science. The solid gains they’ve made over the past 15 years in reading and math haven’t been matched in biology, chemistry and physics. But schools of choice like the one in Orlando are giving hope to science diehards.

Orlando Science School is a charter school, tucked away in a nothing-fancy commercial park, next to a city bus maintenance shop. Founder and principal Yalcin Akin has a Ph.D in materials engineering and did research at Florida State University’s world-renowned magnet lab. His school opened in 2008 with 109 sixth- and seventh- graders. Now it has 730 kids in K-11 and serious buzz as the science school in Orange County, the 10th biggest school district in the nation. Only 26 schools in Florida can boast that 80 percent of their eighth graders passed the state science test last year (the test is given in fifth and eighth grades). At least two thirds were magnets or charters. Orlando Science School was one of them.

The kids are “constantly challenged, which is what you want,” said parent Kathi Martin. One of Martin’s daughters is in ninth grade; the other is in seventh. Mom wasn’t excited about the neighborhood school; the science magnets were too far away; the private schools didn’t feel like home. During a visit to Orlando Science School, she said, something clicked.

It’s “a school where it’s cool to be a nerd,” she said.

In 2006, the Orange County School Board denied the charter’s application. The state approved it on appeal.

Last year, 1,500 kids were on the waiting list. Last month, Orlando Mayor Buddy Dyer paid a visit.

“This is about word of mouth,” said Tamara Cox, the mother of eighth-grader Akylah Cox. “The parents recognize the value of what’s going on at OSS. That’s why there is such a need and such a calling for it.”

For every bad story about charter schools in Florida, several good ones go untold. (more…)

Students know their priorities the moment they enter St. Joseph Catholic School. A sign by the front door reads, “Our Goals: College. Heaven.’’

Inside the West Tampa school’s cafeteria, boys and girls gather for Holy Karaoke, a morning program that encourages them to dance and sing, and focus on the lessons ahead.

Cartoon pumpkins belt out “Blue Moon’’ while bobbing across a giant movie screen. Sister Nivia Arias, in full habit, croons along at the pulpit before prompting her charges to recite daily affirmations.

“We are active learners who do our best work every day,’’ little voices say in unison. “We do the right thing at the right time.”

The saying sums up the philosophy of this 116-year-old parochial school once run by Salesian nuns. It may also be prophetic.

Like other Catholic schools across the nation, St. Joseph struggles with limited resources while trying to attract students and teachers. But a new partnership with the Diocese of St. Petersburg and the University of Notre Dame might be the right thing at the right time.

St. Joseph and another local Catholic school, Sacred Heart in Pinellas Park, are among five schools in the nation taking part in the Notre Dame ACE Academies, a pilot program in conjunction with the university's Alliance for Catholic Education that aims to strengthen Catholic schools and the communities they serve.

The idea is to boost enrollment and help schools develop better leadership, curriculum, instruction, financial management and marketing. (more…)

Catholic schools used to be neighborhood schools. Many of them served immigrant familes. But since 2000 alone, more than 1,700 have closed in the United States, leaving voids in communities and diminishing school choice options for families who could use them now more than ever. In an effort to change that, the University of Notre Dame is leading a partnership that aims to improve the quality of Catholic schools, particularly for low-income, Hispanic families.

The university's ACE Academies program began two years ago in Tucson, Arizona and is now rolling out at two schools in Tampa Bay (St. Joseph in Tampa and Sacred Heart in Pinellas Park). In this redefinED podcast, program director Christian Dallavis notes two important statistics: 1) two thirds of practicing Catholics in the U.S. who are under the age of 35 are Hispanic, and 2) only about 50 percent of Hispanic students graduate from high school in four years.

The university's ACE Academies program began two years ago in Tucson, Arizona and is now rolling out at two schools in Tampa Bay (St. Joseph in Tampa and Sacred Heart in Pinellas Park). In this redefinED podcast, program director Christian Dallavis notes two important statistics: 1) two thirds of practicing Catholics in the U.S. who are under the age of 35 are Hispanic, and 2) only about 50 percent of Hispanic students graduate from high school in four years.

"We see the future of the church is on pace to be kind of radically undereducated," Dallavis said. But "we also have a solution in that we know Catholic schools often put kids on a path to college in ways that they don't have other opportunities to do so."

It's no coincidence the program came to Arizona and Florida. Both states have large Hispanic populations. Both offer tax credit scholarships to low income students.

"They provide a mechanism that allows Catholic schools and other faith-based schools to sustain their legacy of providing extraordinary educational opportunities to low-income families, immgrant communities, minority children, the people on the margins," Dallavis said. "We see the tax credit as really providing the opportunity to allow the schools to thrive going into the future."

But make no mistake. This effort isn't about quantity. The Notre Dame folks know in this day and age, school quality, whether public or private, is essential - and they're looking to beef up everything from curriculum to leadership to professional development. Their goal for the kids: College and Heaven. Enjoy the podcast.

Editor's note: This guest column comes from Julio Fuentes, the president of the Hispanic Council for Reform and Educational Options (HCREO), a national coalition dedicated to education reform that counts civil rights and Hispanic business leaders along with public school teachers and ministers among its supporters.

The history of our education system is marked by pivotal opportunities when leaders and policy influencers joined forces to bring about improvements and policy changes for the betterment of students. From public school desegregation to teacher quality measurements and standardized testing, the landscape of education has evolved and matured to best serve students and their families.

Last week, U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan urged parents, educators and school leaders at the local, state and national levels of government to seize the next of these pivotal opportunities – specifically, he said, we must make Hispanic educational excellence a national priority.

Secretary Duncan noted that the Obama Administration’s goal of having the world’s highest share of college graduates by 2020 will not happen “without challenging every level of government to make the educational success of Latinos a top priority. America’s future depends on it.”

Secretary Duncan’s call to action came in response to a new report from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the U.S. Department of Education’s statistical center, which outlines in grave detail the Hispanic achievement gap that has long been of such concern to my organization and others. Hispanic students are the largest minority group in our nation’s schools, but they continue to fall behind. (more…)