Keith Jacobs II, affectionately called "Deuce," with his parents, Keith and Xonjenese Jacobs. Photos courtesy of the Jacobs family

When our son Keith — affectionately known as “Deuce” — was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at age 3, we were told he might never speak beyond echolalia (the automatic repetition of words or phrases). Until age 5, echolalia was all we heard.

But Deuce found his voice, and with it, a unique way of seeing the world.

He needed to find the right learning environment, with the assistance of a Florida education choice scholarship.

Deuce spent his early academic years in a district public school, supported by an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). Despite the accommodations, learning remained a challenge. We realized that for some, a student’s success requires more than paperwork. It requires community, compassion, and collaboration with the parents.

Imagine having words in your head but lacking the ability to communicate when you need it most. That was Deuce’s experience in public school. His schools gave him limited exposure to social norms and rigor in the classroom. Additionally, through his IEP, he always needed therapy services throughout the school day, which limited his ability to take electives and courses he enjoyed.

His mother and I instilled the importance of having a strong moral compass and working hard toward his social and academic goals. Although we appreciated his time in public school, we knew a change was needed to prepare him for post-secondary education. We applied and were approved for the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities.

Knowing the potential tradeoffs of leaving public school and the IEP structure behind, we chose to enroll Deuce at Bishop McLaughlin Catholic High School in Spring Hill, about 35 miles north of Tampa. We believed the nurturing, faith-based environment would help him thrive. It was the right decision.

Catholic school provided Deuce with the support he needed to maximize his potential. Despite his autism diagnosis, he was never limited at Bishop. He was accepted into their AP Capstone Program. This was particularly challenging, but Bishop was accommodating. The school provided him with an Exceptional Student Education (ESE) case manager dedicated to his success, and he received a student support plan tailored to his diagnosis and learning style. The school didn’t lower expectations; instead, it empowered him to take rigorous coursework with the right guidance.

Any transition for a child with autism will take time to adjust. On the first day, I received a call: Deuce had walked out of class. This was due to his biology teacher using a voice amplifier. The sound overwhelmed Deuce’s senses, and he began “stimming”— rapidly blinking and tapping his hands. Instead of punishing him or ignoring the issue, the staff immediately reached out.

Together, we crafted a Student Success Plan tailored to Deuce’s needs, drawing from his public school IEP without being bound by it. His plan included preferential seating, frequent breaks, verbal and nonverbal cueing, encouragement, and clear direction repetition. For testing, he was given extended time, one-on-one settings, and help understanding instructions.

These adjustments made all the difference.

Throughout high school, Deuce maintained a grade-point average of over 4.0 while taking honors, AP, and dual enrollment courses. Additionally, he was inducted into the National Honor Society and Mu Alpha Theta Math Honor Society while also playing varsity baseball. Because of his success at Bishop, he will continue his educational journey at Savannah State University, where he will major in accounting and continue to play baseball.

Deuce Jacobs earned an academic scholarship to Savannah State University, where he plans to major in accounting and continue playing baseball.

Catholic schools in Florida increasingly are accommodating students with special needs. The state’s education choice scholarship programs have been instrumental in making Catholic education available to more families. Over the past decade, during a time when Catholic school enrollment has declined across much of the nation and diocesan schools have been forced to close, no state has seen more growth than Florida.

At the same time, the number of students attending a Catholic school on a special-needs scholarship has nearly quadrupled, from 3,004 in 2014-15 to 11,326 in 2024-25. Clearly, many families are choosing the advantages of a private school education without an IEP versus a public school with an IEP.

So, I’m puzzled why federal legislation being considered in Congress, the Educational Choice for Children Act (ECCA), includes a mandate that that all private schools provide accommodations to students with special education needs, including those with IEPs.

Although more and more students with special needs are accessing private schools, not every school can accommodate every student’s unique needs (which is also true of public schools). And, as I learned with Deuce, some schools can accommodate students more effectively if they aren’t bound by rigid legal mandates and have the flexibility to collaborate with parents who choose to entrust them with their children’s education.

If the IEP mandate passes, it would prohibit many schools from accepting funds through a new 50-state scholarship program, undermining the worthy goal of extending educational choice options to more families. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has called it a “poison pill” that would “debilitate Catholic school participation.”

Bishop McLaughlin’s willingness to partner with me as a parent not only allowed Deuce to succeed academically but also gave him the dignity and respect every child deserves. IEPs work for many. For others, like Deuce, it takes something more like collaboration to build a path forward together.

President Harry Truman famously opined that incoming president Dwight Eisenhower, a former five-star general, would have a rough go of things.

President Harry Truman famously opined that incoming president Dwight Eisenhower, a former five-star general, would have a rough go of things.

Observed Truman: “He’ll sit here, and he’ll say, ‘Do this! Do that!’ And nothing will happen. Poor Ike—it won’t be a bit like the Army. He’ll find it very frustrating.”

State lawmakers attempting to boss around a vast sprawling field of public schools in their state bring this remark to mind.

I thought we had hit peak utopianism with No Child Left Behind legislation’s goal of 100% student proficiency by 2014, but then the Common Core project came along and instructed otherwise. Neither project ended well, and since 2009, American academic achievement has been in decline.

If lawmakers are on their A-game, they can create incentives and constituencies for improvement, but apparently the failings of the central planning strategy must be continually relearned. State lawmakers have a hard time commanding public school staffs to do things they aren’t keen on doing. Enforcement mechanisms are in short supply, and in the end, the door to the classroom closes and the teachers decide how to spend class time.

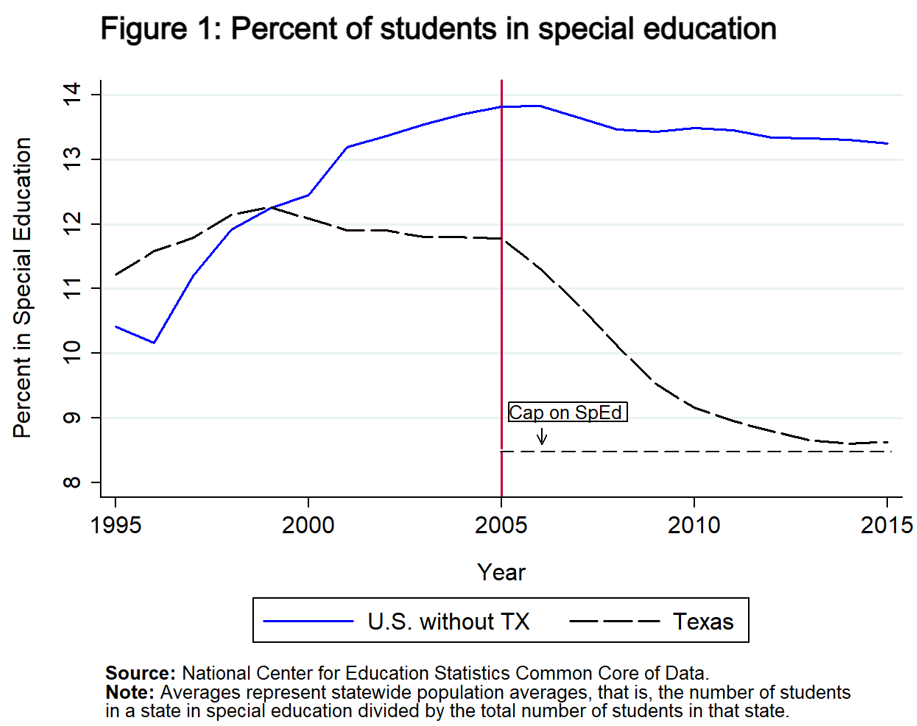

Things might be different, however, if officials in the capitol attempt to compel school personnel to do things they were kind of inclined to do, like when the Texas Education Agency covertly created incentives for public schools to provide fewer special education services. You can’t find evidence of creative or passive resistance evident in this new chart on the Texas cap from the Brookings Institute. Instead, we see rapid compliance:

Brookings has a new study on the Texas special education cap that features this chart. Without public hearings or legal authority, the Texas Education Agency created an entirely arbitrary cap of 8.5% of students in local education agencies (districts or charters) who should receive special education services. If your Local Education Agency served more than 8.5% of students (both the national and the Texas averages were much higher) the Texas Education Agency would audit and otherwise harass you to move you into compliance.

The agency separately created a covert standard on disportionality in special education rates between White and Black/Hispanic students.

Two things are horrible about the above chart. First off is the fact that this misbegotten policy ever existed in the first place, but second is how quickly compliance occurred.

While it is worth noting that some Texas local education agencies did provide more than 8.5% of students special education services, the statewide average for all public schools moved exactly to 8.5% before the Houston Chronicle wrote an expose exposing the practice in 2016.

The Brookings scholars tracked long term outcomes across student groups.

We find that, for students already in SE before the policy went into effect, the likelihood of SE (editor note: special education) removal increased by 13% as a result of capping overall SE enrollment. These reductions in SE access generated significant declines in educational attainment for previously classified SE students, who were 2.7% less likely to complete high school and 3.6% less likely to enroll in college. Lower-income students experienced even larger decreases in high school completion and college enrollment.

Texas schools stopped providing special education services to students at an accelerated rate, they then dropped out of school at a higher rate, and enrolled in college at a lower rate. Now for an entirely different type of horror, consider the second major finding of the study:

Black SE students more intensely affected by the Black disproportionality cap, we find increases in the likelihood of completing high school by 2% and enrolling in college by 4.6%.

Texas kicked Black students out of special education only to observe their high school graduation and college enrollment rates improve. If we are going to go with Occam’s Razor, it seems very likely that a great many of those students never should have been labelled in the first place. Which doesn’t speak well of our system of identifying students for special education services.

I would like to thank Florida’s former Sen. John McKay for pioneering the concept of a choice program for students with disabilities. The latest edition of the American Federation for Children’s guidebook listed 21 states with choice programs for children with disabilities, and new legislation passed this year.

Students in these states have not been entirely left to the tender loving care of a bureaucracy. Parents have options outside the public school system to see to the needs of their children. This is a fundamentally humane policy, and it should be employed everywhere – Texas more than anywhere else.

The central concept of federal special education law is to provide an “Individual Education Plan” for students with disabilities. This is, however, often hollow, and in the case of Texas, authorities charged with carrying out this charge instead covertly executed a plan to deny services.

The best Individual Education Plan is one in which you get to decide who provides services to your child. The worst sort of plans depend entirely upon what a bureaucratic system decides to give you.