This is the latest installment in our series on the center-left roots of school choice, and Part I of a series within a series about school choice efforts in late ‘70s California.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

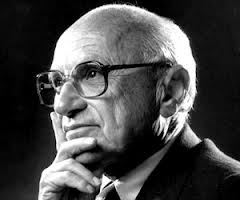

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation. (more…)

This is the second post in our series on the Voucher Left.

Way back in 1978, when Bee Gees ruled the radio and kids dumped pinball for Space Invaders, a couple of liberal Berkeley law professors were promoting a variation on “universal” school vouchers that they believed would ensure equity for the poor. Along the way, they foreshadowed a revolutionary twist on parental choice that would make national headlines nearly four decades later.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman didn’t use the term “education savings accounts” in their book, “Education by Choice.” But they described a sweeping plan for publicly funded scholarships in terms familiar to those keeping tabs on ESAs. They envisioned parents, including low-income parents, having the power to create “personally tailored education” for their children, using “divisible educational experiences.”

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman didn’t use the term “education savings accounts” in their book, “Education by Choice.” But they described a sweeping plan for publicly funded scholarships in terms familiar to those keeping tabs on ESAs. They envisioned parents, including low-income parents, having the power to create “personally tailored education” for their children, using “divisible educational experiences.”

To us, a more attractive idea is matching up a child and a series of individual instructors who operate independently from one another. Studying reading in the morning at Ms. Kay’s house, spending two afternoons a week learning a foreign language in Mr. Buxbaum’s electronic laboratory, and going on nature walks and playing tennis the other afternoons under the direction of Mr. Phillips could be a rich package for a ten-year-old. Aside from the educational broker or clearing house which, for a small fee (payable out of the grant to the family), would link these teachers and children, Kay, Buxbaum, and Phillips need have no organizational ties with one another. Nor would all children studying with Kay need to spend time with Buxbaum and Phillips; instead some would do math with Mr. Feller or animal care with Mr. Vetter.

Coons and Sugarman were talking about education, not just schools, in a way that makes more sense every day. They wanted parents in the driver’s seat. They expected a less restricted market to spawn new models. In “Education by Choice,” they suggest “living-room schools,” “minischools” and “schools without buildings at all.” They describe “educational parks” where small providers could congregate and “have the advantage of some economies of scale without the disadvantages of organizational hierarchy.” They even float the idea of a “mobile school.” Their prescience is remarkable, given that these are among the models ESA supporters envision today.

It's also noteworthy given a rush to portray education savings accounts as right-wing.

In June, for example, the Washington Post described the creation of the near-universal ESA in Nevada as a “breakthrough for conservatives.” School choice would likely be a top issue in the 2016 presidential campaign, the story continued, with leading Republicans like Jeb Bush, Scott Walker and Marco Rubio all big voucher supporters and Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton opposed. The story pointed out Milton Friedman’s conceptualizing of vouchers in 1955, then added, “The idea was long thought to be moribund but came roaring back to life in 2010 in states where Republicans took legislative control.”

It’s true that in Nevada, Republicans took control of the legislative and executive branches in 2014, and then went on to create ESAs. But it’s also true that across the country, expansion of educational choice has been steadily growing for years, and becoming increasingly bipartisan in a back-to-the-future kind of way. Nearly half the Democrats in the Florida Legislature voted for a massive expansion of that state’s tax credit scholarship program in 2010. About a fourth of the Democrats in the Louisiana Legislature voted for creation of that state’s voucher program in 2012. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has been fighting for a tax credit scholarship in that bluest of blue states – an effort in which he’s joined not only by many other elected Democrats, but by a long list of labor unions.

These Democrats are sometimes accused of being sellouts – often by teachers unions and their supporters, who have been especially critical of Cuomo. But the truth is, they can draw on a rich history of support for educational choice grounded in the principles of the American left.

The recent history of ESAs isn’t quite as polarizing as the Post suggests, either. (more…)

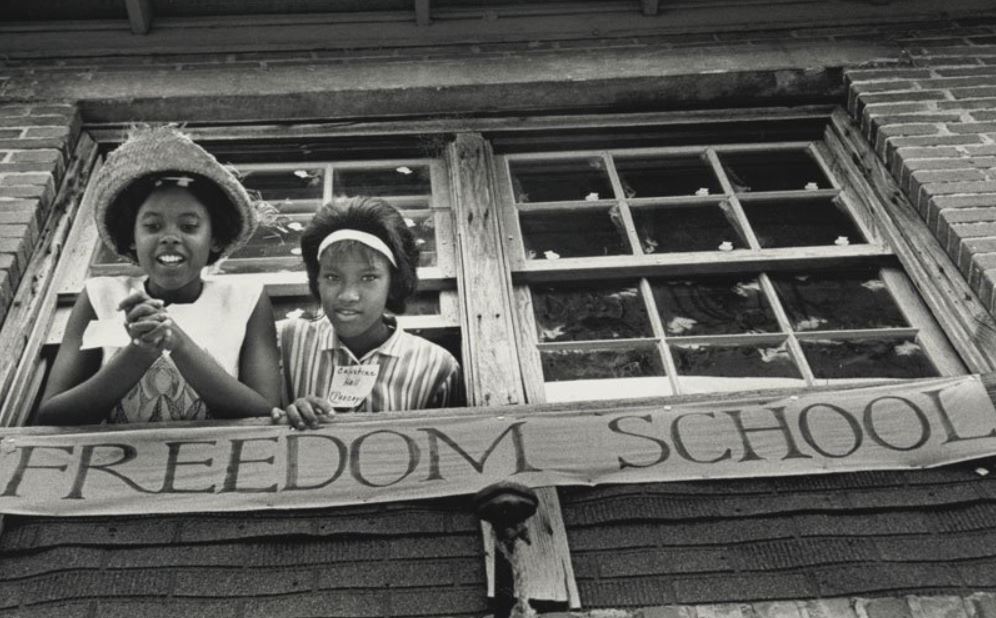

Despite what the story lines too often suggest, school choice in America has deep roots on the political left, in many camps spanning many decades. Mississippi Freedom Schools, pictured above (the image is from kpbs.org), are part of this broader, richer story, as historian James Forman Jr. and others have rightly noted. Next week, we’ll begin a series of occasional posts re-surfacing this overlooked history.

By critics, by media, and even by many supporters, it’s taken as fact: School choice is politically conservative.

It’s Milton Friedman and free markets, Republicans and privatization. Right wing historically. Right wing philosophically.

Critics repeat it relentlessly. Conservatives repeat it proudly. Reporters repeat it without question.

It has been repeated so long it threatens to replace the truth.

The roots of school choice in America run all along the political spectrum. And to borrow a term progressives might appreciate, the inconvenient truth is school choice has deep roots on the left. Throughout the African-American experience and the epic struggles for educational opportunity. In a bright constellation of liberal academics who pushed their vision of vouchers in the 1960s and ‘70s. In a feisty strain of educational freedom that leans libertarian and left in its distrust of public schools, and continues to thrive today.

This is not to deny the importance of the likes of Friedman in laying the intellectual foundation for the modern movement, or to ignore the leading role Republican lawmakers have played in helping school choice proliferate. But the full story of choice is more colorful and fascinating than the boilerplate lines that cycle through modern media. Black churches and Mississippi Freedom Schools are part of the picture. So is the Great Society and the Poor Children’s Bill of Rights. So is U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, D-N.Y., and Congressman Leo Ryan, D-Calif., the only member of the U.S. House of Representatives to be assassinated in office.

Perception matters. Perhaps now more than ever. There is no doubt far too many people who consider themselves left/liberal/progressive and identify politically as Democrats do not pause to consider school choice on its merits because they view it as right-wing and Republican (or maybe libertarian). In these polarized times, people have never identified with ideological and party labels so completely, and, I fear, so often made snap judgements based on perceived alignments.

School choice isn’t the only policy realm to suffer from false advertising, but in the case of vouchers, tax credit scholarships and related options, the myths and misperceptions appear particularly egregious. (Note: I work for Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog and administers Florida's tax credit scholarship program, the largest private school choice program in the nation.) The forgotten history means newcomers to the debate get a fractured glimpse of the principles that have long fueled the movement. And it means critics can more easily cast contemporary supporters on the left as phonies or sellouts, as opposed to what they really are: heirs to a long-standing, progressive tradition.

We at redefinED would like to redouble our efforts to change that. So, beginning today, we’re going to offer a series of occasional posts about the historical roots and present-day fruits of school choice that are decidedly not conservative.

We’re calling it “Voucher Left.”

We hope to offer entries big and small, some by redefinED regulars, some by guests. We may rescue a historical document from the dust bin. We may serve up a profile or podcast. Maybe we’ll reconstruct some fascinating but forgotten moments in the rich history of choice, like what happened in California in the late 1970s when a couple of Berkeley law professors tried to get a revolutionary voucher proposal on the statewide ballot. (Here’s a bit of tragic foreshadowing: But for Jim Jones of the People’s Temple, vouchers today might be considered a liberal conspiracy.)

There is no set schedule for the series. We’ll roll out posts as often as time permits, and as often as we can keep digging up good stuff. Look for the first two right after Labor Day.

In the meantime, a few caveats:

We didn’t coin the term “voucher left.” As far as we can tell, all credit goes to writer (and former fellow at the Center for American Progress) Matthew Miller. In a 1999 piece for The Atlantic, Miller used the term to describe the ‘60s era choice camp that included John E. Coons and Stephen Sugarman, Berkeley law professors who co-founded the American Center for School Choice, which helped put this blog on the map. We thought the term perfect – and just as fitting an umbrella for choice’s other progressive pillars. (more…)

Sad but true: The other day, one of Louisiana’s statewide teachers unions tweeted that the Black Alliance for Educational Options, the stand-up school choice group, supports “KKK vouchers.” It subsequently tweeted, “Tell everyone you know.” (Details here.)

Sad but true: The other day, one of Louisiana’s statewide teachers unions tweeted that the Black Alliance for Educational Options, the stand-up school choice group, supports “KKK vouchers.” It subsequently tweeted, “Tell everyone you know.” (Details here.)

Even sadder but true: This wasn’t an isolated event. In recent months, critics of school choice and education reform have time and again made similar statements and claims – trying to tie Florida’s school accountability system to young black men who murder in Miami, for instance, and in Alabama, trying to link charter schools to gays and Muslims.

But this is also sad but true: Reform supporters sometimes go way too far, too.

Late last week, the Sunshine State News published a story about two Haitian-American Democratic lawmakers in South Florida, both strong backers of school choice, who narrowly lost primary races to anti-choice Democrats. The story quoted, at length, an unnamed political consultant who sounded sympathetic to the arguments raised by school choice supporters. He made fair points about the influence of the teachers union in the Democratic Party; about racial tensions that rise with Democrats and school choice; about a double standard with party leaders when Dems accuse other Dems of voter fraud. But then he said this:

“It’s a kind of ethnic cleansing of the Democratic Party,” he said, according to the report, “centered on the interests of the teachers’ unions.”

School choice critics may often be wrong; their arguments may at times be distorted and inconsistent. But to brand their motivations with a term that evokes Rwanda and Bosnia is more than off-key. It’s repulsive. It’s also a distraction and counterproductive.

I’m floored by extreme statements from ed reform critics. In the past couple of months alone, a leading Florida parents group accused state education officials of using the school accountability system to purposely “hurt children”; a left-wing blogger described John E. Coons, a Berkeley law professor and redefinED co-host, as a “John Birch Society type” because of his support for parental school choice; and other critics used fringe blogs and mainstream newspapers alike to shamelessly tar Northwestern University economist David Figlio, a meticulous education researcher who is not only widely respected by fellow researchers on all sides of the school choice debate but is so highly regarded beyond the world of wonkery that he was cited as a prime example of this state’s “brain drain” when he left the University of Florida. I’m further stumped by how such statements are rarely challenged by mainstream media, and by how more thoughtful critics simply shrug and look the other way.

Attacks like these make me want to say, “At long last, have you left no sense of decency?” But then, at less regular intervals, statements like the ethnic cleansing quote come up and knock reformers off the high road. I’m left with a less satisfying response: “Can’t we all just get along?”

Last week’s commentary in Salon was typical when it comes to the dominant narrative about school choice. Written by Michael Lind, policy director of the Economic Growth Program at the New America Foundation, it describes choice as an “eccentric right-wing perspective” and “an untested theory cooked up by the libertarian ideologues at the University of Chicago Economics Department and the Cato Institute.”

Well-respected newspapers and fringe blogs alike echo that view, though rarely with such creative flourish. The result is a near blackout of a richer, more fascinating and more historically accurate story line – one in which, for decades, if not longer, leading liberals and progressives also thought school choice was a good idea.

Now whether the left has a more compelling case for vouchers and charter schools is a debate for another day. But if more progressives knew their ideological ancestors saw school choice as a powerful tool for social justice, that awareness alone might go a long ways towards creating the conditions where a fair-minded debate is possible.

To that end, we’re introducing a new feature today, "Know Your History," – an occasional effort to highlight school choice’s roots on the political left. Maybe we’ll single out an academic journal article. Maybe we’ll spotlight an old op-ed. Or maybe we’ll get hold of the Congressional document that lists the 24 Democratic senators who supported legislation, introduced in 1978 by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, to give tax credits to families paying private school tuition.

Former redefinED editor Adam Emerson, now writing the Choice Words blog at the Fordham Institute, diligently mined this historical vein during his tenure here (with insightful posts like this one, and this one, and this one). But we’re confident there are plenty of other nuggets worth digging up that will add value to the conversation.

Today’s artifact: a lengthy 1999 piece from The Atlantic. Written by Matthew Miller, “A Bold Experiment to Fix City Schools” sketches the left’s reasoning for embracing vouchers and notes the contributions of John E. Coons, the Berkeley law professor who also serves as a co-host for redefinED. Here’s a taste:

To listen to the unions and the NAACP, one would think that vouchers were the evil brainchild of the economist Milton Friedman and his conservative devotees, lately joined by a handful of desperate but misguided urban blacks. In fact vouchers have a long but unappreciated intellectual pedigree among reformers who have sought to help poor children and to equalize funding in rich and poor districts. This 'voucher left' has always had less cash and political power than its conservative counterpart or its union foes. It has been ignored by the press and trounced in internecine wars. But if urban children are to have any hope, the voucher left's best days must lie ahead.

The voucher left. Has an interesting ring to it, no?

From redefinED co-host Doug Tuthill: Milton Friedman and Jack Coons were intellectual giants in their respective disciplines (Friedman in economics and Coons in law) and strong school choice advocates. But their rationales differed and this led to many interesting - and often contentious - debates. Despite their differences, their debates were always courteous and civil. So when Dr. Friedman died in 2006, his foundation asked Jack to write a chapter in a book honoring Dr. Friedman’s memory, and he agreed. Today is Dr. Friedman’s 100th birthday, so we again asked Jack to share some thoughts on Dr. Friedman, and again he agreed.

Milton Friedman was an economic libertarian of singular intellectual purity. I am less pure, and to me Friedman’s way of modeling the ideal educational triangle of parent, school and child has seemed a simplification limiting our perception of the social implications and, thus, of the politics of choice. I have said all this before. Why, then, do I gladly join this chorus of praise for what I have criticized?

It is not from mere personal fondness for the man. It is, rather, because it was Friedman’s specific application of free market dogma to schools at a particular historical moment that made it possible for a vigorous critique of the American model even to begin. His cry in the night may not have been the first; nor was it the sufficient cause of the great awakening—but it was probably necessary.

Our national mind had long been frozen in admiration of an arrangement comfortable to the middle class, but incapable of realizing education in a democratic way. There is no version of our historic district model of school assignment, even with charter schools, that can in practice achieve what the Europeans honor under the cumbrous but useful title “subsidiarity.” That word warns us to keep authority over the lives of persons either in their own hands or as close to the individual—and in as small a group—as possible. If bowling were our subject, few of us might prefer bowling alone, but neither would we wish to be directed by government to bowl with the people next door.

Left to themselves, humans cluster freely in diverse ways, most of which are innocent and some even creative; their clumps and hives are generally the better for having been chosen. And, if diversity and the smaller unit can serve the purpose, let us lodge the power there.

Subsidiarity could be realized only in a corrupted way by our old district systems. True, some of us can choose to bundle in Beverly Hills, but…and you know the rest of that story; it is daily thrust in our face by the media, and it is true. Many among us just can’t choose Beverly Hills. So at government command my child must learn whatever ideas happen to get taught and whatever behavior gets encouraged in Berkeley.

It was Milton Friedman who in our time rediscovered and announced that this fate of the have-not child was neither efficient nor necessary. A lot of people heard him. Most who did were at first shocked that this sacred cow of democracy, the public education system, had been labeled as a clumsy, self-defeating, anti-social monopoly. But some did begin to listen. And in spite of the system’s sputtering and posturing, they still do. Friedman’s defamation of the schools has begun to stick.

I think he actually underplayed his hand. (more…)

Editor's note: This is the first of two post we're running this week to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the monumental U.S. Supreme Court decision in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, which upheld the constitutionality of the voucher program in Cleveland, Ohio and kicked open the doors for expanded school choice nationwide.

Zelman made clear that the federal constitution allows states to give money to parents that they can use for tuition at religious schools. So long as states don’t directly finance the school itself, no foul. Sadly, some states have constitutions with “Blaine Amendments” that do forbid helping parents this way. These are relics of bigotry; hopefully, the federal courts or sheer political shame will one day erase them.

Would a national commitment to parental choice be a good thing? Think about it. First, remember that the choice of a religious school by parents who pay is a long settled constitutional right. It is widely exercised by those who can afford it. Middle class people in fact have considerable control over where their children enroll and what they learn; they can move to a house in their favorite suburb or they can pay private school tuition.

Clearly, our society is committed to the proposition that parental choice is a social good—at least when made by those who can pay for it themselves. The real issue, then, is whether choice is a good for kid, kin, and country when exercised by families of ordinary means and by the poor.

More bluntly—do we or don’t we want inner-city citizens exercising their rights over their own children? Why have we made it so hard for them? And even where we do allow them to choose a bit (as with public charter schools), what do we, as a society, gain or lose by excluding religious private schools as one among many choices?

Long ago Plato gave arguments for having the state seize complete authority over the child at birth from all families—rich and poor. He thought he knew the one true way and simply did not trust any parent to do right. Maybe there are some platonic arguments for various goods that America achieves when it frustrates choice to the extent it does. Is it somehow productive to snatch the child the child from the authority of ordinary parents for the prime hours of the day for 13 years? What magic is worked by government monopoly over the core experience of the child outside the home?

Is it right that we assume that ordinary parents who cannot afford to pay tuition do not deserve that choice, even if they believe the choice would be best for their children? Crime is, to be sure, more common among lower income groups. But is it less common than it would be if the government were to allow choice? What is cause here and what is effect? Do kids (and all of us) really improve by having complete strangers decide what is worth learning? And do these unchosen strangers do a better job at transmitting the ideas that all of us think important? (more…)

Next week marks the 10th anniversary of the monumental U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris – the decision that upheld the constitutionality of the voucher program in Cleveland, Ohio and accelerated school choice nationwide by describing the conditions under which parents could use public funds to pay tuition and fees at religious schools. To honor the occasion, redefinED will bring you special posts from our partners at the American Center for School Choice.

Next week marks the 10th anniversary of the monumental U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris – the decision that upheld the constitutionality of the voucher program in Cleveland, Ohio and accelerated school choice nationwide by describing the conditions under which parents could use public funds to pay tuition and fees at religious schools. To honor the occasion, redefinED will bring you special posts from our partners at the American Center for School Choice.

On Monday, you’ll hear from John E. Coons, a member of the ACSC board of directors and a professor of law, emeritus, at the University of California, Berkeley. “Do we or don’t we want inner-city citizens exercising their rights over their own children?” he writes. “Why have we made it so hard for them? And even where we do allow them to choose a bit (as with public charter schools), what do we, as a society, gain or lose by excluding religious private schools as one among many choices?”

On Tuesday, ACSC executive director Peter Hanley will weigh in. He takes a closer look at the ongoing court battle over vouchers in Douglas County, Colo., and writes this about some of the legal briefs filed in the case: “Drawing on the historical work of my American Center for School Choice colleagues … the briefs provide a lurid and extensive history of the anti-Catholic bigotry that led to a wave of state constitutional amendments banning funds to support “sectarian” (19th century code for “Catholic”) organizations. They make a compelling case that the trial court not only erred in finding the amendments were violated, but incorrectly ignored this shameful history that means they should be struck down.”

Enjoy.

It’s hard to miss Dick Morris. The former presidential aide and Fox News contributor has raised the volume on his rhetoric during the last couple of days to promote National School Choice Week, and Education Sector’s Kevin Carey was right to note that Morris does more harm to his cause when he harangues the interests and performance of public schools so viciously. But in an otherwise enjoyable essay for The Atlantic, Carey misses an opportunity to further explore how the choice movement evolved to become, as he says, so ideologically "ghettoized." Along the way, he succeeds in guiding us only to familiar territory.

As many do, Carey traces the movement's roots to Milton Friedman's 1955 essay, "The Role of Government in Education," but he dispatches the left turn that school choice made in the 1970s as if it was a political afterthought. In reality, the means-tested policies that facilitate public and private school choice today more closely resemble the proposals from the political left and center that surfaced between the Johnson and Reagan administrations than anything that Milton Friedman sought to test. Greater awareness of that history might not transform the debate, but it could help to lift it from isolation.

Lost to history are the rich Chicago radio debates that took place between Milton Friedman and Jack Coons, who was to champion the cause for equity in the financing of public education and emerged as one of the most stalwart liberal advocates for school choice. To Coons, the poor would show us the right way to develop a proper test for parental choice that extended to private and religious schools, under regulated conditions. He and colleague Stephen Sugarman developed their centrist theory and constitutional framework in their 1978 book, Education by Choice, which drew the attention of a Democratic congressman from California, Leo Ryan. Ryan urged Coons to draft an initiative, saying he would raise the money and organize the campaign. This all happened, of course, before Ryan left to investigate reports of human rights abuses at the Peoples Temple in Jonestown, where he was murdered. Coons and Sugarman began the campaign anyway, confident the money would somehow appear. "Both libertarians and teachers unions laid their curse, and the thing died," Coons would later write.

Around that time, a newly elected Democratic senator named Daniel Patrick Moynihan crafted a measure with Republican Senator Bob Packwood that would have awarded up to $500 in tax credits to families paying private or parochial school tuition. At one point, 24 Democrats and 26 Republicans in the Senate ranging from Sen. George McGovern to Sen. Barry Goldwater signed on as co-sponsors. Moynihan would write that, when the bill was heard, there was a palpable strength felt in the chamber "of the views pressed upon us that this was a measure middle-class Americans felt they had coming to them." Even soon-to-be elected President Jimmy Carter promised, in a campaign message to Catholic school administrators, that he was "committed to finding constitutionally acceptable methods of providing aid to parents whose children attend parochial schools." That was before Carter received the first-ever endorsement from the National Education Association. After he took office, the Moynihan-Packwood measure eventually fizzled.

And this flirtation with history cannot forget the forgettable experiment at Alum Rock, California, home to the nation's first test of school vouchers. Although the experiment took place under the auspices of the Nixon administration, the project began with a team led by the liberal Harvard social scientist Christopher Jencks. "Today's public school has a captive clientele," Jencks would write in Kappan. "As a result, it in turn becomes the captive of a political process designed to protect the interests of its clientele." It was that political process that eventually doomed Alum Rock to a compromise that agreed only to choice within public schools and guaranteed employment for the instructional staff. Just six of the district's 24 schools volunteered to be the educational guinea pig. The experiment lasted just five years.

This isn't just a trip down memory lane. What links these initiatives is a call for equity, and that has precedence in today's targeted voucher and tax credit scholarship laws in Milwaukee, Florida and most other states that have initiated private school options for the poor and disabled, and it has precedence in the positioning of our more innovative educational experiments in the inner city. I wish the organizers for National School Choice Week would do more to point to this Democratic heritage when they highlight the areas where we see growing bipartisan support for choice today, and I wish commentators like Kevin Carey would stop dismissing these points in history as if they had no relevance to our dialogue today. That job might be easier if people like Dick Morris stepped out of the spotlight for a moment.

David Brooks addresses a fictional foreign tourist in today's New York Times by presenting a guidemap to acceptable and unacceptable American inequality. "Dear visitor, we are a democratic, egalitarian people who spend our days desperately trying to climb over each other," Brooks writes, and I'm reminded of a passage in Harvard University professor Paul E. Peterson's book, "Saving Schools," which addressed the fiscal equity movement of the 1970s. Peterson tries to help the reader understand why the equity movement ultimately ran up against entrenched interests, highlighting specifically the challenges redefinED hosts John E. Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman faced when championing the Serrano case in California and the Rodriguez case in Texas. Coons, Sugarman and others had conceived a powerful idea, Peterson writes:

Equal protection before the law implies that all school districts within a state should have the same fiscal capacity. But that idea came up against the basic fact that those with more money want to spend more on their children's education, just as they want to spend more on housing, transportation, and all the other good things in life. To be told that their child's school shall have no more resources than any other school in the state runs counter to the desire of virtually all educated, prosperous parents to see their own children given every educational advantage. Fiscal equity was divisive.

The evidence that Coons and Sugarman had unearthed struck at the inequalities in spending between rich districts and poor districts, and it led the pair on a four-decade long mission to champion the cause of school choice. A commitment to family choice in education, Coons would later write, “would maximize, equalize and dignify as no other remedy imaginable.” Has the opposition to choice led to another form of acceptable American inequality?