Martin Luther King III led a rally in January 2016 that drew more than 10,000 people to Tallahassee in support of education choice in response to a lawsuit brought by the Florida Education Association demanding that the courts shut down scholarship programs in the state.

Editor’s note: You can view a timeline of Step Up For Students’ historical milestones at https://www.stepupforstudents.org/one-million/.

Nearly two decades after Step Up For Students began awarding tax credit scholarships for lower-income students to fulfill their school choice dreams, the organization is marking another milestone: the funding of its 1-millionth scholarship.

Nearly two decades after Step Up For Students began awarding tax credit scholarships for lower-income students to fulfill their school choice dreams, the organization is marking another milestone: the funding of its 1-millionth scholarship.

Over the years, as the concept of education choice has evolved, the scholarship offerings managed by Step Up For Students have changed to fit families’ needs. Today, students can choose from a variety of offerings ranging from the original tax credit scholarship to a flexible spending account for students with special needs to scholarships for victims of bullying. There’s even a scholarship for public school students who need help with reading skills.

“I’ve said from the very beginning my goal was that someday every low-income and working-class family could choose the learning environment that is best for their children just like families with money already do,” said John F. Kirtley, founder of Step Up for Students, the state’s largest K-12 scholarship funding organization and host of this blog.

Kirtley started a private, nonprofit forerunner to Step Up For Students in 1998 and since then has experienced all the milestones and challenges leading up to the millionth scholarship.

At the beginning, “It was just me, and I had enough money to fund 350 scholarships,” recalled Kirtley, who can recite statistics about the scholarship program the way a baseball fan quotes facts and figures about a favorite player.

Soon after, he learned of a new national non-profit, the Children’s Scholarship Fund, started by John Walton of the famous retail family and Ted Forstmann, chairman and CEO of a Wall Street firm. Kirtley connected with that group, which was seeking to match funds raised by partners in different states for economically disadvantaged families to send their children to private schools of their choice.

“We hardly did any advertising at all,” Kirtley said. “It was just me walking around to churches and housing projects talking about the program.”

Truth be told, he didn’t need glitzy marketing. The program drew 12,000 applications in just four months, confirming what Kirtley already suspected: Parents of modest means wanted the best education for their children just as much as people who could afford to pay private school tuition or buy homes in desirable neighborhoods.

In 2001, Kirtley took his pitch to Gov. Jeb Bush, House Speaker Tom Feeney and Senate President John McKay, all of whom strongly supported the creation of the Florida Corporate Tax Credit Scholarship program. When the program, capped at $50 million, began awarding scholarships worth $3,500 in 2002, there were just 15,000 scholarship students. Joe Negron, who sponsored the bill while serving as a state representative and later supported scholarship expansion as a state senator, recalled the strategy he employed to get the bill passed.

“My best argument was that the liberal establishment also supported school choice – for their children, but not for families with modest means,” said Negron, who is now a business executive. “In addition, the personal stories from parents whose students were benefitting from the privately funded program were very powerful.”

High demand created wait lists, prompting lawmakers to raise the cap to $88 million in 2005. The next year, the award increased from $3,500 to $3,750. The state required students to take a nationally norm-referenced test to ensure accountability.

Families kept coming. By 2009, the cap stood at $118 million, with awards at $3,950. Despite the increases, the state’s Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability reported that the program had saved taxpayers $38.9 million in 2007-08.

Shortly after the program was renamed the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, the first state-commissioned evaluation report showed students on the program in 2007-08 experienced learning gains at the same pace as all students nationally. Then in 2010, with bipartisan support, the Legislature approved a major expansion of the program. The bill allowed tax credits for alcoholic beverage excise, direct pay sales and use, and oil and gas severance taxes. The program also could grow with demand.

The Legislature returned again in 2014 to provide another significant boost in response to growing demand, prompting the Florida Education Association, the state’s largest teachers’ union, to bring a lawsuit demanding that the courts shut down the program. Education choice supporters responded with a rally that drew more than 10,000 people to the steps of the state Capitol, including Martin Luther King III, son of civil rights icon Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

King told the crowd, more than 1,000 of whom had ridden buses all night from Miami to attend: “Ultimately, if the courts have to decide, the courts will be on the side of justice. Because this is about justice, this is about freedom—the freedom to choose what’s best for your family, and your child.”

The lawsuit failed in two lower courts and ultimately was rejected by the Florida Supreme Court in 2017.

The Tax Credit Scholarship was joined in 2014 by an attempt to give educational flexibility to students with severe special needs. Florida became the second state in the nation after Arizona to offer educational savings accounts to such students. Named the Gardiner Scholarship program in 2016 in honor of state Sen. Andy Gardiner, a strong supporter who shepherded the bill through the legislative process, the accounts could be used to reimburse parents for therapies or other educational needs for their children.

The state set aside $18.4 million for the program, enough for an estimated 1,800 students. A scant three months later, 1,000 scholarships had been awarded, and parents had started another nearly 3,700 applications. By 2019, the program was serving more than 10,000 students, making it the largest program of its kind in the nation.

Understanding the need for expanding the program so more families could participate, Gov. Ron DeSantis in 2020 approved a $42 million increase to the program, bringing the total allocation to nearly $190 million. The program which served 14,000 students during the 2019-20 school year, expects to serve approximately 17,000 students during the 2020-21 school year.

Choice programs also expanded in 2018 to help two groups of students dealing with challenges. The Hope Scholarship program became the first of its kind in the nation to offer relief to victims of bullying by allowing them to leave their public school for a participating private school. Reading Scholarship Accounts were aimed at helping public elementary school students who were struggling with reading.

Meanwhile, growing demand among lower-income families for Florida Tax Credit Scholarships prompted the Legislature to create the Family Empowerment Scholarship program in 2019. The program operates similarly to the tax credit scholarship program but is funded through the state budget.

Today, the five scholarships serve approximately 150,000 Florida students. As the number of students in the programs has grown, so have educational options available to them.

Charter schools, magnet schools, homeschools and co-ops, learning pods and micro-schools all address different needs. About 40% of students in Florida now choose an option other than their traditional zoned schools. In the Miami Dade district, the state’s largest, that figure is more than 70%.

Step Up For Students founder Kirtley sees a vital need to keep pace with that evolution and to eliminate the inequities these new programs can create for those of modest means.

“I have changed my stated goal to ‘Every lower-income and working-class family can customize their children’s education so they reach their full potential,’ ” Kirtley said, “just like families with more money do.”

Florida Gov. Jeb Bush signed into law in 1999 the A+ Plan for education calling for greater school and teacher accountability eight years after his predecessor signed the Education Reform and Accountability Act.

In 1991, the Florida Legislature passed, and Gov. Lawton Chiles signed, Blueprint 2000: The Education Reform and Accountability Act. The purpose of Blueprint 2000 was to restructure how Florida’s public education system was managed.

In the late 1980s, Florida was a national leader in experimenting with teacher empowerment and site-based decision making (SBDM). The SBDM movement sought to transfer more decision-making power to schools in exchange for these schools being held more accountable for results. Blueprint 2000 was designed to create a state policy infrastructure that would institutionalize SBDM across all of Florida’s public schools.

Legislative and executive branch leaders, all of whom were Democrats, thought Florida’s public schools were underperforming because they were being micromanaged. Blueprint 2000 was going to change that.

I was one of four teacher union representatives on the state commission appointed in 1991 to develop the Blueprint 2000 implementation plan. In collaboration with the Florida Department of Education and thousands of educators, parents, business leaders, and other citizens, we created new state curriculum standards, a new state assessment system called the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT), established School Advisory Councils (SACs) at every public school, and required schools to implement annual School Improvement Plans (SIPs). We failed to reach consensus on how best to hold public schools accountable for results, a failure Jeb Bush fixed when he became governor in 1998.

Next spring will be Blueprint 2000’s 30-year anniversary. Florida’s public education system has made great improvements using the education reform and accountability infrastructure that sprang from Blueprint 2000. But that infrastructure has aged. Florida’s public education system needs a new blueprint. It is time for Blueprint 2030.

The COVID-19 pandemic is forcing educators and parents to innovate at a pace never before seen in public education. In the period of a month last spring, every district, private, and charter school campus closed and every student became a homeschool student. When school begins this fall, families will choose from a variety of instructional models, including on-campus, virtual, hybrid (i.e., a combination of on-campus and virtual) and homeschooling. In coming years, families will have access to even more choices.

State government has waived a variety of state laws and regulations to allow schools and families to adjust to this new normal. But these waivers are temporary solutions. Our state leaders need to start developing a new public education infrastructure, and Blueprint 2000 provides an approach they could consider emulating.

Similar to what the Florida Legislature did in 1991, the 2021 legislature could pass legislation establishing a commission to develop recommendations for creating a new public education infrastructure. This new infrastructure should be designed to support a more diverse and flexible public education system, one capable of meeting the unique needs of each student.

The largest task for this commission would be improving Florida’s antiquated public education funding system. This funding system is hostile to systemic innovation and the flexibility needed to meet each student’s needs.

The state has created flexible spending accounts for some students with unique abilities/special needs. About 16,000 families will use this spending flexibility this fall to customize their child’s education. Providing all families with access to flexible public education funds is necessary if all children are to benefit from a customized education program.

We also need to reinvent our state assessment and assessment data systems. As students increasingly receive publicly-funded instruction from multiple providers (tutors, virtual school, college via dual enrollment and assigned neighborhood school) we will need to assess the progress students are making with each provider, aggregate their achievement data, and properly share students’ data with those providers.

We also will need to institutionalize better processes for helping families and students pick the most appropriate providers. Well over 10,000 providers are eligible to serve the 16,000 unique abilities/special needs students using flexible spending accounts, often called Education Scholarship Accounts (ESAs). Deciding which of these 10,000 providers is the best fit for a specific learning need is a daunting task.

A Blueprint 2030 commission will have a huge job helping state government, school districts, schools and other education providers create the infrastructure necessary to support an effective and efficient post-pandemic public education system. We are never going back to the pre-pandemic education system.

Planning for the future should begin soon.

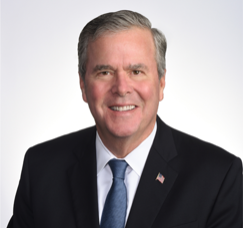

Earlier this week, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush joined Education Next editor-in-chief Marty West to talk about the lessons he learned dealing with crisis and how those lessons can be applied to the coronavirus pandemic and the challenges it poses for K-12 education.

Among the suggestions Bush offers state and national leaders: Be clear and transparent, connect on a human level, and gather the best possible minds regardless of political persuasion.

“Just as in every disaster or every disruptive time in world history, incredible things happen when you’re forced to do things,” Bush says. “Because you have no other option, generally, you do them.”

Listen to the podcast at https://www.educationnext.org/ednext-podcast-jeb-bush-on-adjusting-to-distance-learning-during-pandemic-covid-19-coronavirus/.

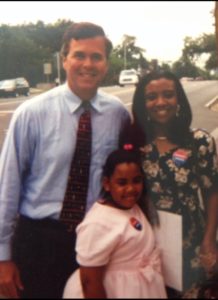

Tracy James and her daughter, Khaliah Clanton-Williams, are greeted by principal Maria Mitkevicius and administrator Mary Gaudet at the Montessori School of Pensacola. Khaliah

participated in Florida's Opportunity Scholarship program in early 2000. PHOTO: Michael Spooneybarger

Editor’s note: During this holiday season, redefinED is republishing our best articles of 2019 – those features and commentaries that deserve a second look. This article from Step Up For Students’ director of policy and public affairs Ron Matus was part of our “Education Revolution” series marking the 20th anniversary of the far-reaching K-12 changes Gov. Jeb Bush launched in Florida. Originally published May 30, it spotlights a mom and daughter who participated in Florida’s historic Opportunity Scholarship.

PENSACOLA, Fla. – Tracy James finished the graveyard shift to find her car a casualty of the “voucher wars” – and her 8-year-old, Khaliah, needing another ride to school.

This was 20 years ago, when this Deep South Navy town became the front in the national battle over school choice. In June 1999, Florida’s new governor, Jeb Bush, had signed into law the Opportunity Scholarship, the first, modern, statewide, K-12 private school voucher in America. Khaliah and 56 other students in Pensacola were the first recipients, and now enmeshed in a political clash drawing global attention.

CNN came. A Japanese film crew showed up. So did a member of British Parliament. All wanted to see the “experiment” a Canadian newspaper said “will shape the future of public education in this state and perhaps across the United States.” Tracy and Khaliah were in the thick of it, with Tracy among the most outspoken of an unconventional cast of characters. The single mom with the self-described rebel streak wouldn’t hide her joy at this opportunity for her only child – and refused to cave to anybody who suggested she was being “bamboozled.”

“If you want something better for your children,” she told one paper, “you would do the same thing.”

Not everybody appreciated her resolve.

Tracy walked out of her shift as a phlebotomist to find her car sabotaged, three tires flat as week-old Coke. She called her dad, who said he could take Khaliah to her new school, one Tracy could not afford without the scholarship. The flats left Tracy shocked and ticked – and more determined.

I guess I need tougher skin, she thought. Because we ain’t going back.

Lots of folks know Ruby Bridges. But Khaliah Clanton-Williams? Maybe one day.

The original Opportunity Scholarship students, their parents, and the five private schools that welcomed them have never gotten their due. After an epic legal battle, the Florida Supreme Court ruled the school choice program unconstitutional in 2006, and the decision in Bush v. Holmes seemed to close the chapter. But it didn’t. Many of those whose lives were touched by the scholarship have untold stories, with some still unfolding in ways that attest to the power of that experience.

In one sense, the Opportunity Scholarship was as small-scale as it was short-lived. Students were eligible if their zoned public schools earned two F grades in a 4-year span, and in 1999 only two schools – both in Pensacola – fell into that category. At the same time, most private schools sat it out. Among other restrictions, the law barred them from charging tuition beyond the scholarship amount of $3,400 to $3,800. At its height, the Opportunity Scholarship served 788 students.

And yet, it loomed so large. Florida’s “first voucher” stirred the imagination about what could be with a more pluralistic, parent-driven system of public education. It exposed the festering dissatisfaction many parents had with assigned schools. It enabled and amplified voices that still aren’t heard enough.

Pensacola may be best known for its Blue Angels and sugar-sand beaches. But most of the parents who applied for the school choice scholarships were working-class black women – nursing assistants and bank tellers, cooks and clerks, Head Start workers and homemakers. They had a lot to say about schools in Pensacola’s low-income neighborhoods, and for a few months in 1999, they had the mic.

***

Khaliah’s assigned school was modest red brick, five blocks from her home, named for the district’s first “supervisor of colored schools.” Khaliah would be starting kindergarten, so Tracy stopped to visit. She never got past the front office. “It was a zoo,” she said. “Kids were running around. They were screaming. There was no discipline. There was no structure.”

Nobody with the school acknowledged her, so after a few minutes, Tracy left … for good. She turned to her only option: another district school near her mother’s house, two miles away. Tracy said her mom, a former custodian for the school district, became Khaliah’s guardian so Khaliah could attend. But that school didn’t pan out either.

One day, Tracy watched through a window as kids in Khaliah’s class danced to music blaring from a boom box. She found the teacher in a side office and asked what was going on: “ ‘She said, ‘It’s reading time.’ I said, ‘They’re not reading.’ “ Tracy opened her eyes wide for emphasis.

Khaliah, meanwhile, shy and soft-spoken, was falling behind. “I had a hard time concentrating because it was so loud,” she said. “I’d ask for help and it was like, ‘just a moment.’ But the moment never came.”

Tracy heard about Opportunity Scholarships while working another job as a hotel desk supervisor. Some guests asked her in passing about local schools, and as fate would have it, they were lawyers with the Institute for Justice, the firm that would later help defend the scholarship in court.

Ninety-two students applied for the scholarships, including Khaliah, who had come back to live with Tracy. That exceeded the available seats in the four Catholic schools and one Montessori that opted to participate, so a lottery was held.

Khaliah emerged with a golden ticket.

***

Tracy took her time before deciding on a school. She read up on Catholic schools, talked to friends and co-workers who attended Catholic schools, learned everything she could about Montessori. She was intrigued by the latter – by the mixed-age classrooms, the cultivation of creativity, the curriculum that was so different. In the end, the rebel and her daughter decided they wanted different.

Khaliah Clanton-Williams, left, used an Opportunity Scholarship to attend the Montessori School of Pensacola.

Khaliah attended Montessori School of Pensacola from second through seventh grade, and, in Tracy’s words, “blossomed” in confidence and knowledge. She returned to public school in eighth grade (Tracy wanted her re-acclimated to public school before high school) and graduated from Pensacola High in 2010. For most of the next few years, she worked as a mortgage loan officer. She earned her associate degree in business administration from Pensacola State College in 2018. She’s on track to earn a bachelor’s in human resources management (with honors) in 2020.

Without the Montessori, Khaliah said, much of that would not have happened.

“It made me better,” she said. “I don’t think I would have gone to college. I don’t think I would have gotten my degree. (Montessori) made education more important. It was a higher standard.”

The upside wasn’t just academic. Tracy and Khaliah said nearly everyone in the school embraced Khaliah as family. There were only a few black students before a few more enrolled with the scholarships, but race was not a divide, they said. Khaliah made fast friends. They invited her to sleepovers, to ride horses, to U-pick blueberries. “These things were normal to them, but not to me,” she said.

Montessori co-owner (and head of elementary and middle school) Maria Mitkevicius said increasing diversity was a big reason the school opted into the scholarship program. So was the belief the school shouldn’t be limited to parents of means.

The staff knew the stakes, even if they didn’t know how much things might change. Twenty years after five private schools and 57 kids cracked the door, at least 26 private schools in Escambia County (Pensacola is the county seat) participate in Florida’s K-12 school choice scholarship programs, serving at least 2,163 students. Statewide, 2,000 private schools serve more than 140,000 scholarship students, with thousands more on the way.

“We thought this might change the face of education,” Mitkevicius said. “I guess it did.”

***

The news on Pensacola TV showed 10,000 sign-waving students and parents, marching at a 2016 school choice rally in Tallahassee with Martin Luther King III. As Khaliah watched it again last week, tears fell.

It hurt, she said, to see so many who still don’t have choice or fear their choices could be taken from them. At the same time, how nice to see strength in numbers.

“Back then,” she said, meaning 1999, “it was just us.”

Tracy James and her daughter, Khaliah, with former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush circa 1999.

Remembering back then is tough for Tracy too. Some in Pensacola’s black community could not understand why black parents would support anything connected to Jeb Bush. “We were looked on as kind of those people who are being arm twisted by the governor, like you’re letting the Republicans bamboozle you,” said Tracy, now a clinical recruiter for a Pensacola hospital.

It got ugly. Dirty looks. Heated words. The tires. Tracy said some friends and family stopped speaking to her, and she switched jobs because she felt she was being harassed for taking a stand.

But the rebel has no regrets.

“I wanted to try something different, I wanted to be different, I wanted a different opportunity for my daughter,” Tracy said. “From what I saw happening, I wanted to be able to make the choice, myself, of where she’d end up as an adult.”

“I had no idea that it’d turn out to be such a controversial issue,” she continued. “To be thrown into sort of the limelight of a political battle, I had no idea. I had absolutely no idea how important it would be.”

Or how much of a struggle.

“When we went through that program, I was thinking that was kind of the end of an era,” Tracy said. “But it was actually the beginning.”

***

The shy girl who helped pioneer school choice is now a tough-minded mom who needs more.

Khaliah is married to a paper mill machine operator, and their oldest, Kyrian, will begin kindergarten this fall. His zoned school is one of 11 D-rated schools in the district, so like her mom before her, Khaliah looked for alternatives. She applied to three higher-performing district schools through an open enrollment program, but all were full. On a second go-round, Kyrian got into a new elementary north of Pensacola. It’s not ideal. The drive will be up to 45 minutes each way, and Khaliah switched jobs – to drive for Shipt, Lyft and Uber – so she can have flexibility.

Still, she’s worried. Kyrian has special needs – he’s hyperactive, averse to change in routine and undergoing speech therapy – but has not been formally diagnosed with anything. At this time, he wouldn’t qualify for any of Florida’s private school scholarships.

The irony isn’t lost on Tracy and Khaliah. School choice helped them. They helped pave the way for more. Yet 20 years later, there still isn’t enough choice for Kyrian.

The rebel’s daughter said that just means the work isn’t done.

“I’ll continue to fight for my children as my mom fought for me,” Khaliah said. “I’m not taking no as an option.”

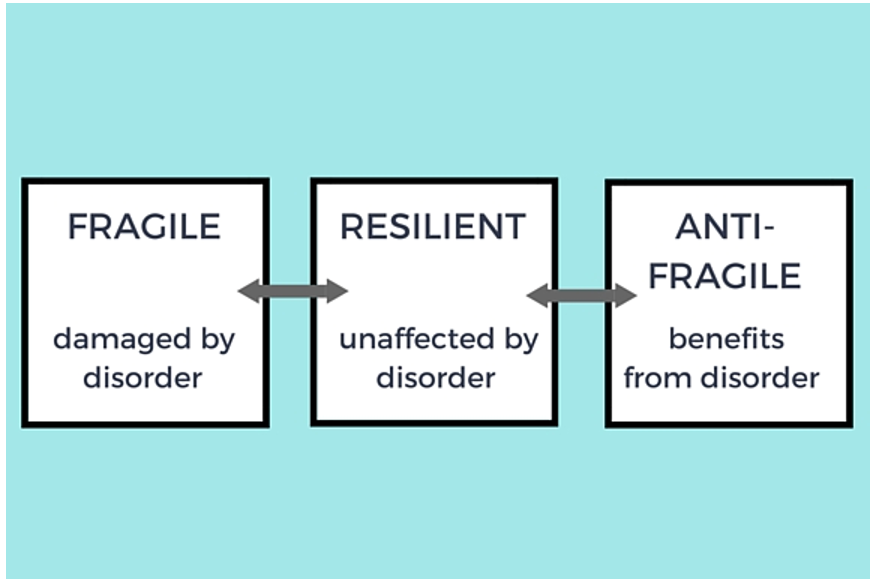

We tend to think of K-12 schooling systems as delicate. Cut their funding a bit and their performance falls apart. But what if we were to envision a K-12 schooling system that is anti-fragile, using the concept developed by Nassim Nicholas Taleb?

We tend to think of K-12 schooling systems as delicate. Cut their funding a bit and their performance falls apart. But what if we were to envision a K-12 schooling system that is anti-fragile, using the concept developed by Nassim Nicholas Taleb?

Under Taleb’s definition, systems that are anti-fragile aren’t necessarily hard to break; rather, they simply get stronger when placed under stress. Exercise is a ready example of an anti-fragile system. Exercise tears down muscle, but then that muscle grows back stronger than it was before.

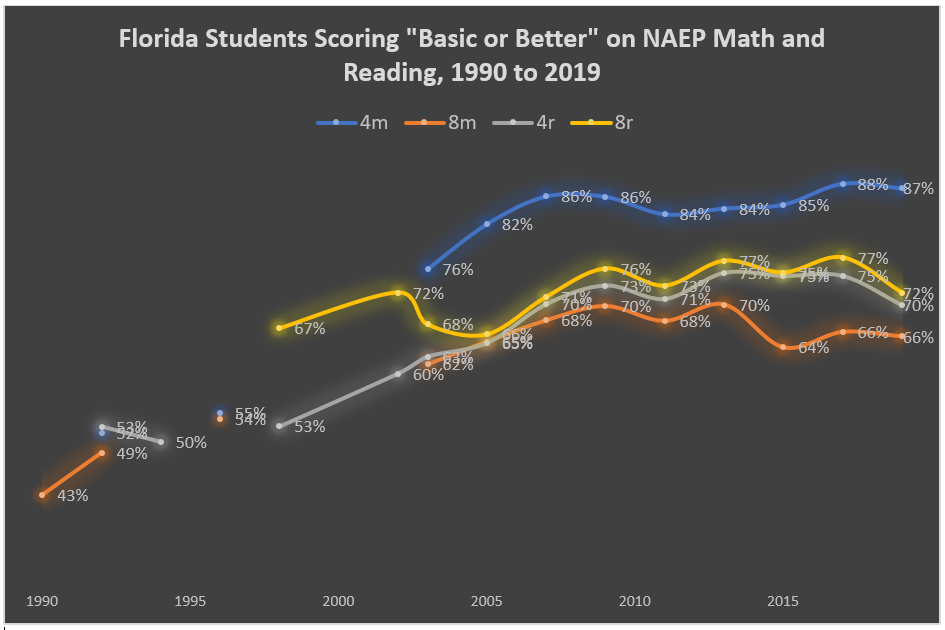

Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush appeared to place his state’s education system under a policy-induced stress during his two terms from 1999 to 2007. The Florida Education Association didn’t much care for it, mortgaging its Tallahassee headquarters in a (fruitless) effort to defeat Bush’s 2002 reelection bid. Florida academic outcomes, however, clearly improved during that period.

The Obama-era effort to incentivize states and create a teacher evaluation system based on test scores was another effort to create a healthy stress for the K-12 system. Alas, I am unable to create a broadly encouraging national chart similar to the one above (national performance was flat on both NAEP and PISA), but what may loom increasingly over the next decade is a severe competition for public dollars. It may, in fact, more closely resemble the Great Recession than a purposeful K-12 strategy.

Arizona has the best example of an anti-fragile K-12 system. The Great Recession drop-kicked that state’s housing-heavy economy with a steel-tipped boot. State general fund revenue dropped 20 percent in 2009 and the rapid enrollment growth Arizona had enjoyed since World War II suddenly stalled.

Despite Obama stimulus money and a temporary sales tax increase, K-12 per-pupil funding experienced some of the largest cuts in the country. Arizona charter schools already received less funding per pupil than Arizona’s (modestly) funded districts, and then those funds were cut along with everything else. As an Oxford debate is to a punk rock mosh pit, so is 1999-2007 Florida K-12 to the Great Recession in Arizona.

So, what happened with academic outcomes in Arizona charter schools during this difficult period?

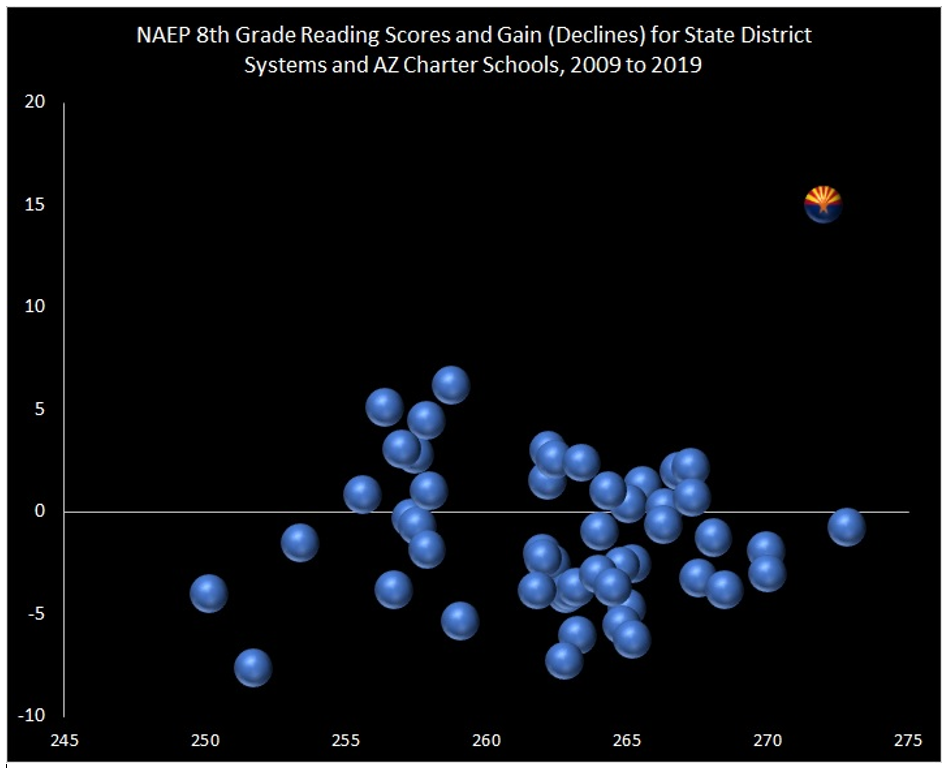

At around 200,000 students, Arizona’s charter sector is about the size of a large American school district and more than twice the size of the Wyoming public school system. It also educates a mostly minority student body at a level of per-student subsidy compared to systems nationally. This chart shows eighth-grade NAEP reading absolute scores and gains/declines for Arizona charters compared to state district systems from 2009 to 2019.

Math looks very similar, as do the Science exams. Arizona charters also show high achievement on the state AZMerit exam, and an analysis of transfers shows that on average, they send students to districts with above-average AZMerit scores and receive from districts transfers with below-average scores.

So: This system is looking anti-fragile; funding got cut, but achievement rose. This anti-fragile system of schools draws its strength from the fragility of undesired schools.

The Great Recession hit Arizona’s economy early and hard. Charter operators with long waitlists and strong track records who were able to access capital financing despite the downturn found inexpensive facilities in abundance. Charters that had been struggling with parental demand before the downturn folded under the weight of their difficulties. The Arizona charter school sector overall grew rapidly in size and simultaneously in average levels of achievement.

Far from extraordinary, this is perfectly normal in most human endeavors. Firms with services and products in high demand grow to meet demand, while those with low demand close. When placed under severe stress, Arizona charter schools became much stronger (as did Arizona K-12 education as a whole; Arizona alone made statistically significant gains on all six NAEP exams during the 2009 to 2015 period). It’s very rare in public education, however, that districts routinely face community pressure to keep under-enrolled schools open and school boards routinely fold under this pressure.

Likewise, many districts have high-demand schools with waitlists, but those schools commonly are kept as niche players rather than scaling to meet demand. The dynamic here is the same. Incumbent interests would see a scaling high-demand district offering as a threat to the employment/operations of other schools in the district.

Few districts, therefore, display antifragility; undesired schools remain in operation despite diverting funds from classroom use, high demand schools don’t get the opportunity to replace low demand schools, and frustration abounds for decades as we try – and largely fail – with top-down schemes to spur greater productivity from a system that largely lacks the ability to dynamically improve.

Winston Churchill once noted that Americans will always do the right thing once they have exhausted all the other possibilities. Education is not an exception.

Happy holidays, and see you in 2020!