David Osborne recently predicted academic doom for red states having recently passed universal private choice programs. “This will accelerate the process of the rich getting richer while the poor fall further behind,” Osborne asserted. Osborne problematically ignored our nation’s actual experience with universal choice programs, making his column more a litany of faith than a clear-eyed analysis.

Osborne predicts a bleak future for states with universal private choice programs, with poor families left behind. Osborne prefers a charter school model of choice, keeping choice within the public realm of regulation and accountability:

"Is there an alternative, other than the status quo of struggling public school systems? Indeed there is. States and school districts could reduce bureaucratic controls, empower educators and increase choice, competition and accountability for performance within the public school system, through the spread of charter schools. Cities that have done so, including New Orleans, Washington, D.C., Denver and Indianapolis, have produced some of the nation’s most rapid improvements in student performance."

Arizona lawmakers created the first universal private choice program in 1997, the nation’s first scholarship tax credit program. Decades passed before another state enacted a private choice law with equally expansive eligibility. Three years earlier, in 1994, Arizona lawmakers had created two de facto public universal choice programs in the nation’s most robust charter school law and a statewide district open enrollment statute. “Large” and “relatively lightly regulated” would accurately describe Arizona choice programs, both public and private. Arizona lawmakers expanded and supplemented scholarship tax credits repeatedly; the Arizona charter sector became the largest among states, and open enrollment between and within districts dwarfed both in combination. Arizona created the nation’s first education savings account program in 2011 and expanded eligibility several times before making it universally available to Arizona K-12 students in 2022.

Given Osborne specifically cites four jurisdictions with the sort of choice programs of which he approves- Denver, Washington D.C., New Orleans, and Indianapolis, it seems in order. The Stanford Educational Opportunity Project provides academic growth data by jurisdiction (schools, counties, and states) and student subgroups for the 2009-2019 period. Comparing the rate of academic growth for low-income students in each of these four jurisdictions with those of Arizona counties in Figure 1:

Academic growth is a very important academic measure. While raw scores are very strongly correlated with student demographics, growth is much less so. Scholars widely view academic growth as the best measure of school quality. Many years into exposure to universal choice programs, Arizona’s low-income students seemed to be too busy learning to suffer Osborne’s predicted calamities. Greenlee County is a rural and remote area of Arizona with approximately 1,500 students and (alas) no charter or private schools during the period covered by the data. In this measure, a “zero” basically entails having learned a grade level worth of material per year on average, so the performances for Denver, DC and Orleans Parish are respectable, Marion County (host county of Indianapolis) less so.

The Stanford Educational Opportunity Project also measures the gap in learning rates by subgroup, which is measured by subtracting the learning rate of poor students from that of non-poor students. The four jurisdictions lauded by Osborne ranked first, second, third, and fifth in comparison to Arizona counties in terms of the amount of learning rate inequality between poor and non-poor students. There was exactly one state that had a positive rate of academic growth for both poor and non-poor students and had a faster rate of academic growth for poor students. It is the state marked “1” and spoiler alert…it is Arizona, the host of multiple universal choice programs.

Osborne’s hypothesis held that what some would regard as wild, lightly regulated “let it rip” choice programs would prove to be a disaster for low-income students, and conversely, well-regulated choice programs should advantage the poor. In practice, however, we find evidence to support the opposite conclusion. These results would not have surprised Milton Friedman in the least:

The results in the above figure also sit comfortably with the diagnosis of John Chub and Terry Moe, who identified politics as the central flaw of the American public school system. The American public school system does not do a terrific job on average in educating students, but it does a fantastic job in maximizing the political power and revenue of employee unions and their associated fellow travelers. Attempting to set up a governance structure of politically disinterested technocrats who will give families just the right amount of freedom and just the right amount of regulation comfortable for technocrats is an appealing theory. In practice, the most powerful and reactionary forces in modern American politics hijack the project easily unless a powerful, supportive constituency rises to defend the programs.

Shea Middle School in the revitalized North 32nd area of Phoenix offers the AVID program to prepare students for college and houses the North Valley Arts Academy, a rigorous arts experience.

Every so often, someone active in the curriculum reform movement will get frustrated and take time out of his or her schedule to denounce the school choice movement.

These folks tend to make obscure statements about “governance” or “structural” reform along the way to building a case that they have the one true faith that can improve education for all children. And they can produce a tremendous amount of evidence to support their curricular preferences.

Curriculum does matter. This reform tribe, however, apparently lacks a broad appreciation for politics and the mechanisms by which their preferences were largely driven out of the K-12 system.

John Chubb and Terry Moe explained back in 1990, and it bears frequent repeating, that the main problem with American K-12 is politics. Chubb and Moe did not use this exact terminology, but the American system of district schooling is very prone to the phenomenon of regulatory capture. This is the same phenomenon that leads state regulatory boards on banking, cosmetology, chiropractors or (fill in the blank here) to be quickly dominated by bankers, hair stylists and chiropractors or (fill in the blank here again).

The diffuse public interest is not organized. Your interest in state chiropractor policy is not something you think about, but it is something of intense interest to practitioners in the industry. Thus, through the normal and predictable workings of politics, such boards, intended to regulate industries they oversee, tend to be “captured” by special interests.

American school boards are elected. A certain brand of K-12 traditionalist will even sing the praises of local democracy in schooling. School board elections, however, are very vulnerable to regulatory capture. Single-digit turnout rates in school board elections happen routinely. Elections typically are non-partisan and low-profile. Highly motivated special interests such as unionized employees and major private contractors don’t find it dauntingly difficult to field working majorities on school boards.

Contractors make money building things and providing goods and services for districts. They aren’t likely to have strong preferences on curriculum. The same can’t be said for the unions. Their preferences, along with a large majority of college of education faculty, seem either actively or passively opposed to the preferences of curriculum reformers. Evidence has piled up that some forms of teaching reading and other subjects are more effective than others, and that disadvantaged children have been the primary victims of poor pedagogy for decades.

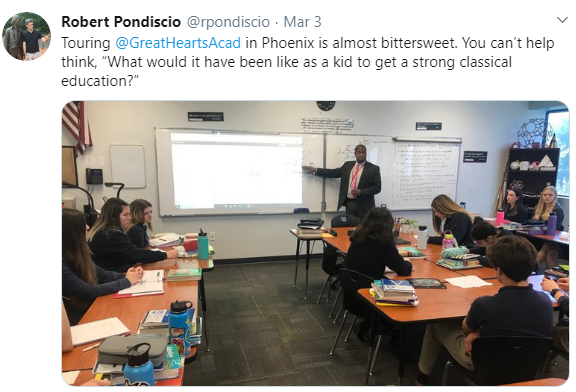

Curriculum reformers should support choice mechanisms such as charter schools and private choice programs because they create the opportunity for educators with minority viewpoints (think Core Knowledge fans) to create schools fulfilling their education vision. For instance, when Robert Pondiscio toured a Phoenix charter school recently, he tweeted:

Sometimes at this point in the conversation, curriculum reformers will raise the objection that focusing on choice means ignoring the district schools where most students attend. Nothing could be further from the truth. Back in 2013, this same classical education-focused charter group announced that it planned to open a school in my neighborhood. The image that introduces this post is a photo I took of my zoned district middle school’s response.

Giving educators and families the power to create a demand-driven system of schooling isn’t just a path to improving curriculum; so far as I can tell, it is the most effective path. Classical education is flourishing in Arizona and elsewhere because parents want it for their children and educators are willing to move heaven and earth to provide it to them.

Choice creates an incentive for districts to give parents the education they want. So curriculum reformers can either continue to bang their heads against the wall waiting for a future when they get to be the ones in control of curriculum, or they can go about the hard work of creating schools, revealing demand and making progress.

One of these strategies has a future; the other does not.

I wish the education reform movement would put more focus on the broken schools of education that fail to attract highly qualified students or to train them to perform well in the nation’s classrooms.

Six years have passed since The Education Schools Project, headed by Arthur Levine, former president of Teachers College at Columbia University, issued a comprehensive and scathing indictment of the nation’s schools of education. The report found an overwhelming lack of academic standards and understanding of how teachers should be prepared. It determined that “most education schools are engaged in a ‘pursuit of irrelevance,’ with curriculums in disarray and faculty disconnected from classrooms and colleagues.” Moreover, schools of education have become “cash cows” for universities. The admissions standards are low. The research expectations and standards are far below those expected in other disciplines. And there is no pressure to raise student academic outcomes because, at least in part, school districts often only care about a “credential” and not the learning it represents.

Six years have passed since The Education Schools Project, headed by Arthur Levine, former president of Teachers College at Columbia University, issued a comprehensive and scathing indictment of the nation’s schools of education. The report found an overwhelming lack of academic standards and understanding of how teachers should be prepared. It determined that “most education schools are engaged in a ‘pursuit of irrelevance,’ with curriculums in disarray and faculty disconnected from classrooms and colleagues.” Moreover, schools of education have become “cash cows” for universities. The admissions standards are low. The research expectations and standards are far below those expected in other disciplines. And there is no pressure to raise student academic outcomes because, at least in part, school districts often only care about a “credential” and not the learning it represents.

Have things improved since Levine’s report? Speaking at a panel during the recent Excellence in Action National Summit on Education Reform, Kate Walsh, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality, previewed the results of a comprehensive study to be published in U.S. News & World Report in April 2013. It affirms little has changed. For example, only about 20 percent of schools of education have admission standards that even require applicants to be in the top 50 percent of their high school graduating class. Only 25 percent of schools of education require their students to be placed with an “effective” teacher when student teaching. (more…)