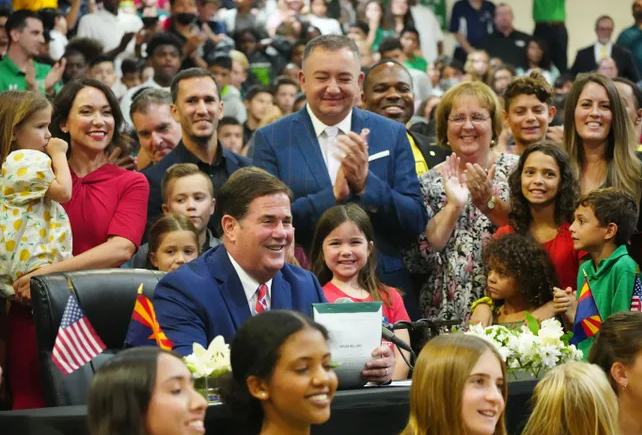

Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey at signing ceremony for bill that massively expanded education savings accounts

Editor's note: This post was originally published on realcleareducation.com. The author, Jude Schwalbach, is an education policy analyst at Reason Foundation.

After an Arizona citizens’ referendum failed to block the state’s massive expansion of Empowerment Scholarship Accounts last month, the Grand Canyon State now leads the nation in education customization.

Arizona’s education savings account (ESA) expansion was a critical school-choice success, but the story should not stop here. Policymakers can do two things that go beyond Arizona’s reforms to truly revolutionize a state’s education system: make ESAs the default option for all students and eliminate residential assignment in public schools.

First, policymakers should not limit ESAs to those opting out of public schools but rather make these accounts the default funding system for all students. Instead of funding school districts based on factors such as property wealth, local tax effort, and complex formulas, state and local education funds would be streamlined and deposited into each student’s account.

Under this system, these accounts would not just be used for private school tuition payments. Parents who enroll their children in public schools would pay these schools directly and could also use education savings accounts to pay for tutoring, courses at a community college, classes at a nearby public school, transportation, and more.

To continue reading, go here.

During the Falklands War of 1982, the British managed to land troops. The Argentine air force, however, sank the cargo ship with the helicopters the British planned to use to transport themselves to the capitol city of Port Stanley.

During the Falklands War of 1982, the British managed to land troops. The Argentine air force, however, sank the cargo ship with the helicopters the British planned to use to transport themselves to the capitol city of Port Stanley.

As a consequence, the British “yomped” 90 kilometers – just over 55 miles – by foot over three days, carrying their gear with them. They won the war without their helicopters.

American families: By the time you read this post, there will be a large new wave of school closures across the country, despite the expenditure of untold billions of federal dollars, despite policies putting school staff many moons ago at the front of the line for vaccinations, despite the less severe nature of the current variant.

Once again, the education unions are pushing for closures, making it even more difficult for anyone to ignore the elephant in the K-12 room: If you are the parent of a school- age child, you need to develop self-reliance.

Both visibility and turnout in school board elections is very low, creating a ripe environment for what economists describe as “regulatory capture.” Elected officials are most responsive to the folks who get them elected, and alas, that isn’t you.

If you’re skeptical about this, quiz yourself on the number of seats on your local school board and try naming any of the members. If you can come up with correct answers to either of these questions, give yourself a gold star, because neither I nor 99% of our fellow Americans can do so.

Regulatory capture in school boards by unionized employee interests and major contractors isn’t normally so obvious, but 2021 was anything but normal. Apparently, abnormal will be sailing well past any fine lines and continuing into 2022.

Out of necessity, American families have developed a spirit of self-reliance in education. Micro-schools have flourished. Home-schooling soared to record levels. Lawmakers, responding to constituent demand, passed a record number of choice bills in 2021.

Perhaps they will do better still in 2022.

The British soldiers on the Falklands tundra knew that Britain was 8,000 miles away and that they wouldn’t be getting a new set of helicopters. Just in case anyone missed it in 2021, events are reminding American families again that the ultimate responsibility to educate their children lies with them.

Districts stuffed with extra federal billions but struggling to hire bus drivers and a scarcity of special education aides and substitute teachers making it challenging for schools to remain open can be likened by a large and growing number of American families to a cargo ship sitting on the floor of the Atlantic.

Graduate training in the social sciences teaches students to think in terms of a multi-variable world. Humans naturally gravitate toward simple explanations of reality, such as X caused Y, when in fact isolating the impact of X on Y with reliability is very difficult.

Graduate training in the social sciences teaches students to think in terms of a multi-variable world. Humans naturally gravitate toward simple explanations of reality, such as X caused Y, when in fact isolating the impact of X on Y with reliability is very difficult.

Random assignment studies are the most useful in this regard, but these sorts of studies are difficult and expensive to arrange, and many policies do not lend themselves to random assignment. Many times, we have little choice but to make decisions based upon lesser evidence.

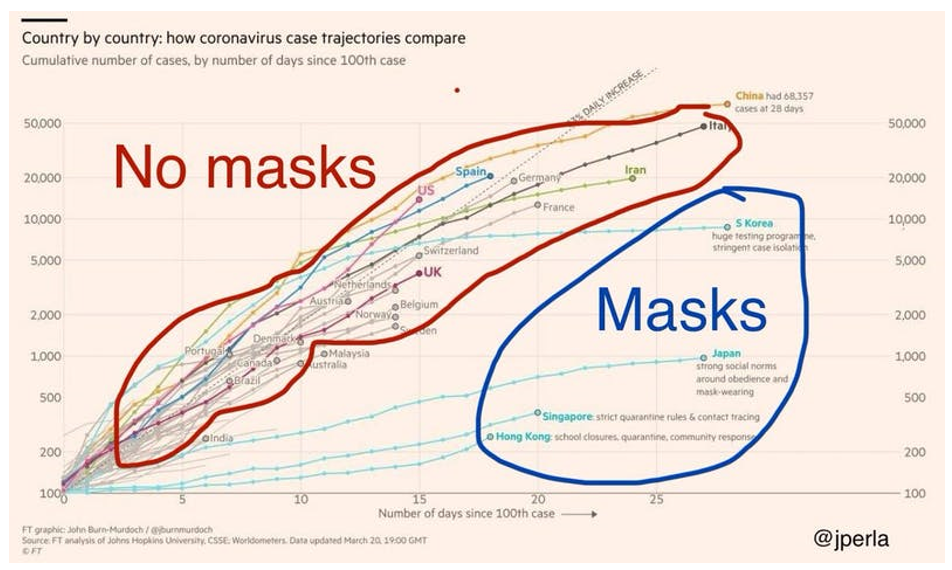

The social scientist is trained to look at technology leader Joseph Perla’s chart above and say, “We shouldn’t assume that South Korea, Japan and Singapore are having a good pandemic because of masks. It could be something else, or it could be multiple other factors. Masks could actually be bad.”

This is all potentially true. Moreover, unless you are willing to randomly assign people to wear masks in public and prevent the control group from wearing them, you cannot know for sure.

Policymakers, on the other hand, do not have the luxury of epistemological nihilism. They must make decisions, almost always based upon incomplete or otherwise imperfect information.

President Harry Truman once said: “Give me a one-handed economist. All my economists say, 'on hand...', then 'but on the other ... ’”

So, while the social scientist looks at this chart and suspects foul play, the pragmatist looks at it and says, “Well, there could be other things going on, and masks could still be playing a positive role.”

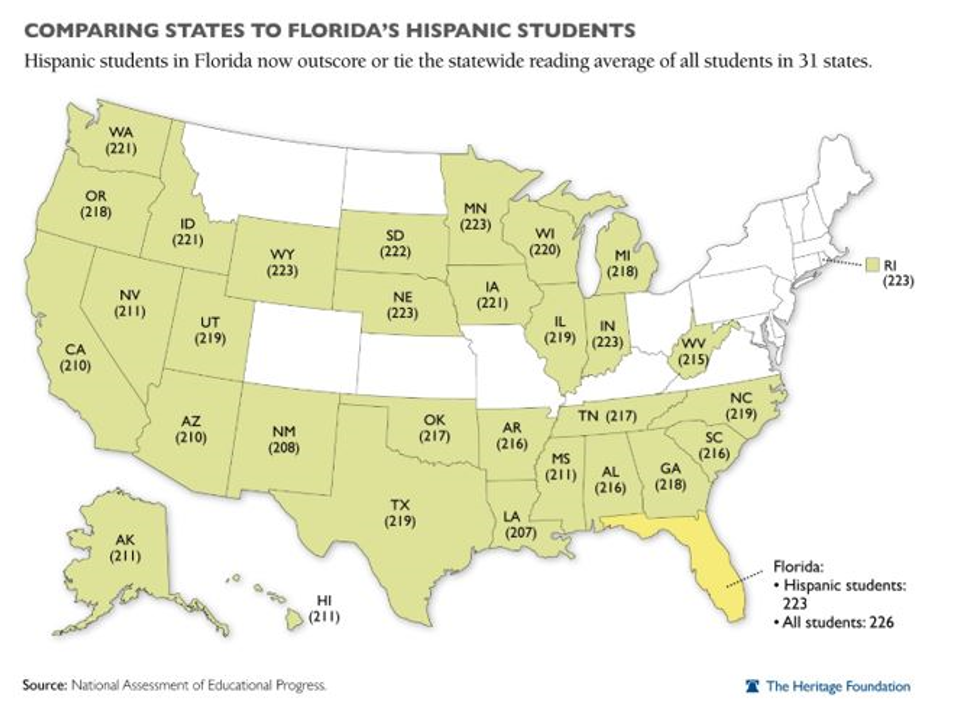

K-12 policy also gets made in a chaotic world with multiple policy changes occurring at the same time. Back when I collaborated with the Heritage Foundation to produce the map below comparing the fourth-grade NAEP scores of Hispanic students in Florida to the statewide averages for students across the country, critics raised the social science objection: “You don’t know which Florida policy led to the increase,” was the essence of the complaint.

This was entirely correct from the point of view of the social scientist, but the pragmatist in me required me to say: “Since we don’t know which of the many reforms in the Florida cocktail led to the improvement, don’t take any chances – implement all of them.”

Likewise, someone might want to study everything Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore have done to prevent the spread of COVID-19. It is not necessarily the same approach. But right about now, encouraging people to wear masks in public is looking like a pretty good idea, not dissimilar from studying a state whose minority students score a grade level higher than your statewide average on reading.