Editor's note: This story on the latest scores released from the National Assessment of Educational Progress originally appeared Wednesday in The 74.

COVID-19’s cataclysmic impact on K–12 education, coming on the heels of a decade of stagnation in schools, has yielded a lost generation of growth for adolescents, new federal data reveal.

Wednesday’s publication of scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) — America’s most prominent benchmark of learning, typically referred to as the Nation’s Report Card — shows the average 13-year-old’s understanding of math plummeting back to levels last seen in the 1990s; struggling readers scored lower than they did in 1971, when the test was first administered. Gaps in performance between children of different backgrounds, already huge during the Bush and Obama presidencies, have stretched to still-greater magnitudes.

The bad tidings are, in a sense, predictable: Beginning in 2022, successive updates from NAEP have laid bare the consequences of prolonged school closures and spottily delivered virtual instruction. Only last month, disappointing results on the exam’s history and civics component led to a fresh round of headlines about the pandemic’s ugly hangover.

But the latest release, highlighting “long-term trends” that extend back to the 1970s, widens the aperture on the nation’s profound academic slump.

To continue reading, go here.

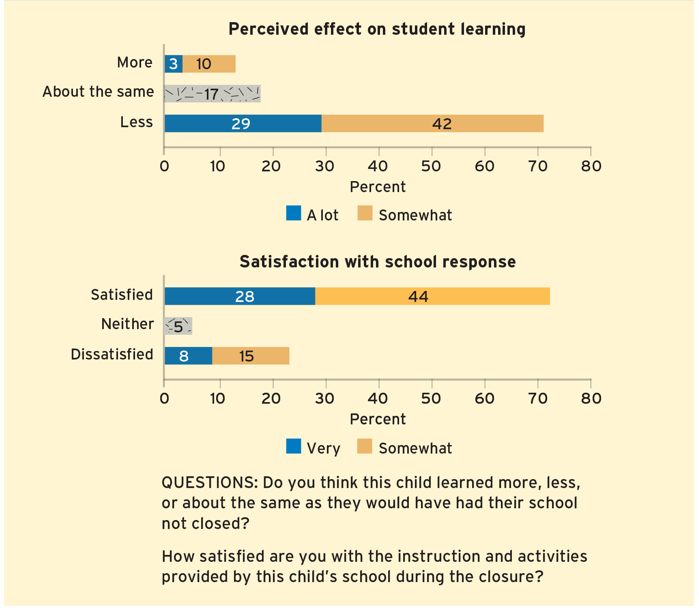

A new Education Next survey reveals 71% of parents perceived their children learned less during the pandemic than they would have had they remained in brick-and-mortar schools.

COVID-19 upended and changed the lives of millions of Americans this spring, forcing the nation’s schools to close and requiring a shift from in-person to virtual learning. In retrospect, what do parents think about the quality of instruction their children received?

Education Next surveyed them to find out. The results, released earlier this week, paint an interesting picture.

Among the 1,249 parents of 2,147 children surveyed, 71% said they thought their children learned less at home than they would have had they been in school. But surprisingly, 72% said they were satisfied with the attempt.

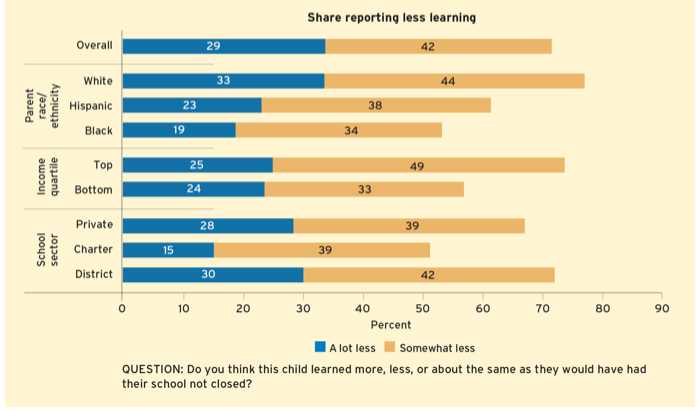

Black and Hispanic parents reported higher satisfaction with remote learning (30% and 32%, respectively), than white parents (26%). Charter school and private school parents (45% and 39%, respectively), reported higher satisfaction than parents whose children attended a public district school (29%).

According to their parents, larger shares of the children of white respondents and children in higher income households learned less than they would have if schools had remained open than children of Black and Hispanic students and those in lower-income households.

Not all schools prioritized learning new content according to the survey. Overall, 74% of parents said their child’s school introduced new content, while 24% said the school focused on reviewing content students had already learned.

A large gap in perception persisted between high- and low-income families. Among low-income families, 33% reported that schools reviewed content students had already learned, compared to 19% of high-income parents.

Parents overall reported that one-on-one meetings between students and teachers occurred rarely, with only 38% saying such meetings occurred at least once a week. About 40% said one-on-one meetings never occurred.

Parents reported that class-wide meetings occurred more frequently, with 69% reporting class-wide virtual meetings with teachers occurred at least once a week.

Black parents reported their children spent more time per day (4.3 hours) on schoolwork than white parents (3.1 hours). Black parents also said their students suffered less learning loss than the parents of white students.

The survey also included a sample of 490 K-12 teachers who work in schools that closed during the pandemic. Teachers’ responses generally mirrored how parents described their children’s experiences with several exceptions.

Thirty-six percent of teachers said they met individually with students multiple times a week, compared with 19% of parents. Teachers also reported providing grades or feedback more often than parents. Meanwhile, teachers reported providing fewer required assignments than parents said their children received.

Parents and teachers generally agreed on how much students learned during distance learning, with teachers more likely than parents to say children learned less than they would have if schools had remained open.

The survey was conducted from May 14 to May 20 by the polling firm Ipsos Public Affairs via its KnowledgePanel. Respondents could elect to complete the survey in English or Spanish.