Each KaiPod learning pod is led by a dedicated KaiPod Learning Coach to provide small-group and one-to-one academic support.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Michael B. Horn, co-founder of and distinguished fellow at the Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation, appears in the Fall 2021 issue of Education Next.

In a Historic House museum in Newton, Mass., nine children seated at three tables configured in a U-shape are each working on their own online lesson. After their 25-minute “Pomodoro” cycle – a time-management technique designed to optimize one’s ability to focus on a specific task – they break for a variety of outdoor recreational activities from badminton to Bananagrams.

The children are enrolled in KaiPod Learning, a program that offers small-group learning pods with access to virtual schools, in-person tutoring and support, and a variety of student-driven enrichment activities. The day I visited, many, but not all, of the students planned to join a yoga session in the afternoon.

KaiPod is among the startup pods that emerged from the height of the pandemic and that have so far survived.

In the summer of 2020, the frenzy around learning pods, also called microschools and pandemic pods, was high. As described in “The Rapid Rise of Pandemic Pods” (What Next, Winter 2021), families, including mine, were frenetically assembling or joining them out of a desire to preserve some in-person support, community, and normalcy in an otherwise abnormal year.

At the same time, equity concerns and parent shaming ran rampant. Educators, researchers, and the media worried about who would have access to these pods and whether low-income families would be left out of them.

A year later, the scene looks different. While the Delta variant has kept plans changing, people seem more interested in a return to in-person schooling. The conversation around pods hasn’t vanished, but it has quieted. Many families, including my own, pulled out of their pods last year because they found them unsustainable for any number of reasons.

And yet many pods that have an institutional structure behind them, rather than being fully parent-run, have survived. They are finding their niches and growing. Despite fears that pods would benefit only people in prosperous suburbs such as Newton, some of the most robust pod experiments have taken place in school districts disproportionately serving low-income and minority students.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This post from Center on Reinventing Public Education senior analyst Steven Weiner on why so many teachers don’t want to return to traditional classrooms appeared Tuesday on The 74.

Editor’s note: This post from Center on Reinventing Public Education senior analyst Steven Weiner on why so many teachers don’t want to return to traditional classrooms appeared Tuesday on The 74.

Samantha had been a veteran educator for 14 years, first as a classroom teacher and then a principal, when the pandemic shut down schools. Last year, when she learned about the then-growing learning pod movement, she thought starting one would help solve several immediate problems.

“[My daughter] needs social interaction,” she said in an interview. “I know there’s other kids out there that need social interaction. I know there’s working parents out there that could use the support of somebody like me, and then it just snowballed from there.”

Running a learning pod turned out to be a transformative experience for Samantha.

“This is probably the most professionally satisfied I’ve ever been in my entire career,” she said. And she felt there was no turning back: “[After] this experience, I’m not going back to formal K–12 education. I can’t. You can’t. I want to be able to replicate what I had here. You can’t do that in public school.”

Samantha was not alone in her sentiment. This spring, when Center for Reinventing Public Education researchers surveyed and interviewed teachers who worked in learning pods, we were struck by how many preferred these learning environments over their prior schools.

The learning pods that proliferated during the 2020–21 school year were unplanned educational experiments that often looked far different than a standard school. They took place in living rooms, community centers, and even neighborhood parks.

Many were started by parents who either hired professional educators or took on the role of teacher themselves, often as a complement to their regular school’s remote instruction.

Learning pods were generally small, with most averaging about six students, though they could still be logistically complicated to run. Along with her daughter, Samantha hosted four other elementary schoolers ranging from first to fourth grade and juggled their remote schedules, which shifted throughout the year between synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid in-person varieties.

“We’ve literally been on nine different schedules since we started,” she said during our interview last March.

To continue reading, click here.

The fluid nature of the pandemic catalyzed a “new” solution – supplemental learning pods – with approximately 12% of parents enrolling their children in learning pods as a supplement to their core school.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Bruno Manno, senior adviser to the Walton Family Foundation’s K-12 Program and reimaginED guest blogger, appeared Monday on The 74.

COVID-19 school shock disrupted our way of doing education, unbundling the familiar division of responsibilities among home, school and community organizations.

Nearly every parent of school-age children had to create from scratch a home learning environment using online technology, rebundling school services to meet their needs. Most parents accepted whatever teaching, learning and support services their district offered, supporting their child’s learning as best they could.

Other parents sought new learning options.

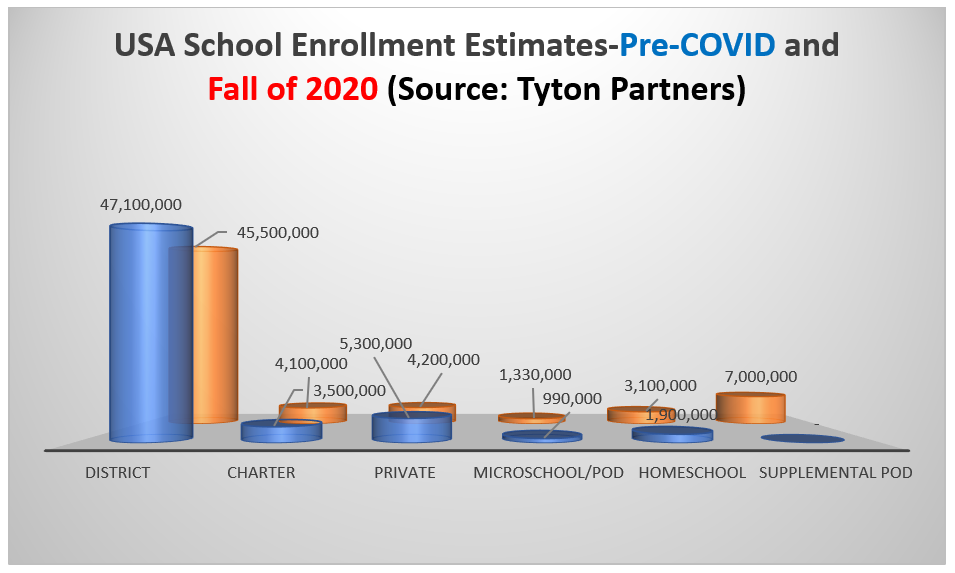

A study from Tyton Partners calculates that during the 2020-21 school year, 15% of parents changed their child’s school, a rate 50% higher than pre-pandemic levels. Overall, 2.6 million students exited district and private schools, enrolling in charter schools, homeschooling, microschools and other options. Thirteen percent of families also enrolled their child in small learning pods, supplementing traditional school.

In doing so, these parents exercised their agency to work with like-minded community members, many of whom were outside the current K-12 system — call them civic entrepreneurs — to create new organizations or expand existing ones to meet this demand.

There is now an unprecedented amount of K-12 federal dollars — around $190 billion and counting from three new pandemic-related programs — for people and programs to remedy the huge academic, social and emotional toll that COVID-19 imposed on young people and their families, with 90% ($171 million) going to school districts. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that local districts may not exhaust stimulus dollars until 2028.

To continue reading, click here.

Kahn Academy, a nonprofit educational organization that provides free online resources to teachers, parents and students, has expanded programming to school districts, partnering with around 200, up from nine pre-pandemic.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Bruno V. Manno, senior advisor to the Walton Family Foundation’s K-12 Program and a reimaginED contributor, appeared Monday on RealClear Education.

Back-to-school stories this year will focus, naturally, on the Covid-19 pandemic’s toll on students and families and on remedying these difficulties.

But another story is being shortchanged: It’s about how parents sought new options for their children like homeschooling, small learning pods, and micro-schools, with civic entrepreneurs and their partners creating new organizations or expanding existing ones to meet this demand.

This story suggests a promising path forward for K-12 education – parent-directed, student-centered, and pluralistic, offering more educational and support options to families.

The story begins with the pandemic shock to our way of schooling. The lockdowns unbundled the familiar division of responsibilities between home, school, and community organizations, with parents eventually rebundling school services to meet their family’s needs.

The result: nearly 18% of parents changed their child’s school, a figure 75% higher than historical averages. Thirteen percent also enrolled their child in small learning pods, supplementing regular school. Overall, 2.6 million students exited district and private schools, enrolling in charter schools, homeschooling, micro-schools, and other options.

This familiar American story of disruption spurring new capacity and innovation has three lessons for shaping the future educational landscape.

First, many parents don’t want “the old normal.” Two of three parents (66%) would rethink “how we educate students, coming up with new ways to teach.” Only one-third believe that schools “should get back to the way things were.” More than half (53%) support pods, with Black and Hispanic parents (60%) more supportive than white parents (53%). Overall, only 14% oppose them.

To continue reading, click here.

Prenda launched in 2018 with seven students. The network had grown to more than 400 microschools by fall 2020.

Editor’s note: To learn more about education choice in New Hampshire, check out SUFS president Doug Tuthill’s podcast with New Hampshire state Rep. Glenn Cordelli here.

Signaling its continued support for education choice and parental empowerment, the New Hampshire Department of Education has announced that four districts – Bow, Dubarton, Fremont and Haverhill – have been awarded Recovering Bright Futures Learning Pods grants from the state to address learning loss due to the pandemic.

The Department has partnered with Prenda, a tuition-free network of microschools, to create small, in-person, multi-age groupings where students can learn at their own pace, build projects and engage in collaborative activities. Prenda will utilize the grant funds on a per-pupil basis to serve Learning Pod enrolled students, who will remain enrolled at their district school.

Each learning pod will be supported by a certified learning guide and will follow a project-based learning model. All families can access the learning pods as space allows.

The concept of learning pods may be new to many, New Hampshire Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut said, but they’ve already served more than one million students across the country.

“Learning pods are particularly helpful to students who have experienced learning loss and will thrive with more individualized attention,” Edelblut said.

Learning programs in district learning pods have been aligned with New Hampshire Academic Standards and adapted to individual students. Prenda will be responsible for providing quarterly updates to the district on student performance criteria and attendance will follow district practices.

All New Hampshire school districts, including traditional and public charter schools, as well as home education families, are eligible to participate in the District Learning Pod program. The Department expects additional school districts in the state to sign on for the program.

While many learning pods that existed before the pandemic as afterschool programs or summer camps returned to their pre-pandemic programming, others, like this one in Calabasas, California, continued to operate, offering promising innovations on the original concept.

Editor’s note: This analysis from Alice Opalka, a research analyst with the Center on Reinventing Public Education, appeared today on The 74. It originally published on CRPE’s education blog, The Lens.

Over the past school year, the Center on Reinventing Public Education has tracked how pandemic learning pods evolved from emergency responses to, in some cases, small, innovative, and personalized learning communities.

This summer, as COVID-19 vaccinations increased, it seemed like the major impetus for these efforts was fading from view. We turned to our existing database of 372 school district- and community-driven learning pods to answer this question: How sustainable is the learning pod movement?

That question has taken on greater urgency as new, more transmissible variants of the virus raise new safety fears — especially for children too young to be vaccinated — and school systems explore options for families who remain hesitant to return to normal classrooms.

Our analysis found clear evidence that a little over one-third of the learning environments we tracked operated through the end of the school year. But we also identified promising evolutions of the original concepts that will continue into next school year. While, in the short term, most students will likely return to some sort of “normal” school model, the lessons of these small learning communities have the potential to persist in new ways.

Public school learning models changed considerably between our last update in February and the end of the school year. Though there were school districts that remained fully remote through the school year, by the end of the year most districts had added at least some in-person options which would, in theory, minimize the need for many of the learning pods in our database since many of them were designed to provide in-person support and internet connections to students who were learning remotely.

If pods continued after school districts resumed in-person instruction, that offers some evidence families valued the alternatives to traditional classrooms that they provided.

We found that 37% of all learning pods identified in the database operated through the full 2020-21 school year. Half of the pods were “unclear,” meaning there was no clear end date to the pod-like offerings, but also no clear indication they continued through the end of the year. Only 12% had definitively closed at some point before the end of the year.

It’s possible that many of the “unclear” pods also ceased school-day support but never updated their websites or social media to make the announcement.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This post from Bruno V. Manno, senior adviser to the Walton Family Foundation’s K-12 Program and a redefinED contributor, appeared Tuesday on The 74. Manno references Florida Virtual School, which saw a 57% increase in new course enrollments in its part-time Flex program, in his discussion of how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the face of K-12 education.

Editor’s note: This post from Bruno V. Manno, senior adviser to the Walton Family Foundation’s K-12 Program and a redefinED contributor, appeared Tuesday on The 74. Manno references Florida Virtual School, which saw a 57% increase in new course enrollments in its part-time Flex program, in his discussion of how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the face of K-12 education.

“Never in my lifetime have so many parents been so eager for so much education change.”

So said longtime pollster Frank Luntz after surveying 1,000 public and private school parents on how the pandemic affected their view of schools.

COVID-19 forced schools to change from being buildings where teaching, learning and programs were bundled together to serve students and families to a menu of services and choices that parents were forced to piece together — rebundle — to meet their needs.

The potential long-term result could be a more student-focused, parent-directed and pluralistic K-12 school system.

The consulting firm Tyton Partners estimates COVID-19 shock produced a 2.6 million-student decrease in district and private schools, with charter schools, homeschooling, micro-schools and other alternatives gaining enrollment. The U.S. Census reports homeschooling enrollment increased from 5.4 to 11.1 percent of households. African Americans registered a fivefold increase, from 3.3 to 16.1 percent.

What other alternatives did parents choose as they worked to rebuild their child’s schooling?

One was family-organized discovery sites, aka pods — gathering small groups of students, in person or virtually, with added services like tutoring, childcare or afterschool programs. San Francisco Mayor London Breed opened 84 pods serving around 2,400 children, about 96 percent racial minorities.

The Columbus, Ohio, YMCA offered pods for students aged 5 to 16 attending schools virtually, with arrival as early as 6 a.m. JPMorgan Chase offered discounts on virtual tutors and pods for eligible employees using Bright Horizons, its employer provider, and opened its 14 childcare centers for employees’ children’s remote learning at no cost. Organizations like SchoolHouse, LearningPodsHub and Selected for Families helped parents start pods, organizing teachers and tutors.

To continue reading, click here.

And these children that you spit on

And these children that you spit on

As they try to change their worlds

Are immune to your consultations

They're quite aware of what they're going through

David Bowie, Changes

A district school superintendent recently told me: “COVID has kicked the education reform can down the road 15 years. I’m not sure we are all aware of the implications yet, but the belief that we are returning to 2019 ‘normal’ is folly.”

Wired reported this month on the increase in homeschooling during 2020:

In 2019, homeschooled students represented just 3.2 percent of U.S. students in grades K through 12, or around 1.7 million students. By comparison, 90% of U.S. students attend public school. But a March 2021 report from the U.S. Census Bureau indicates an uptick in homeschooling during the pandemic: In spring 2020, 5.4% of surveyed households reported homeschooling their children (homeschooling being distinct from remote learning at home through a public or private school).

By fall 2020, the figure had doubled to 11.1% … The U.S. Census Bureau’s survey indicates that homeschooling rates increased across all ethnic groups in the past year, and the greatest shift was among Black families, who reported a 3.3 percent rate of homeschooling in spring 2020 and 16.1% later in the fall.

Tyton Partners made another set of estimates based upon a survey of parents. Nothing looks revolutionary at first glance in these estimates, but look closer and you can feel the earth shift under your feet.

The Tyton estimates show a less profound (but still sizeable) move to homeschooling. You probably shouldn’t get overly attached to either estimate because the situation is very fluid, and we’ll know better in the fall. Even if the Tyton numbers are closer to reality, as the Wired article notes, the ease with which people can homeschool has increased, as have the incentives to do so.

There will be no putting this toothpaste back in the tube.

If the Tyton estimates are accurate, district and private schools will have suffered their largest single-year declines in history while charter schools, micro-schools and homeschools enjoyed large increases in enrollment, and supplemental pods emerged spontaneously to educate 7 million students. We see, for instance, a rate of charter school enrollment almost four times that of the average between 2000 and 2018. The shakeup likely isn’t finished.

The largest decrease in enrollment nationwide came from kindergarten students, with parents choosing to “redshirt” rather than enroll them in fall 2020. A National Public Radio survey of 100 school districts found an average kindergarten enrollment drop of 16%.

Assuming most of those families choose to enroll for fall 2022, schools likely will have to shift teachers out of first-grade assignments (where there will be fewer students) into kindergarten assignments (where there will be more). Which school sector they sort themselves into and at what rate also will be of interest. A back-of-the napkin estimate of the number of redshirted kindergarteners based upon the typical size of recent cohorts and the 16% figure would fall between 500,000 and 600,000 students.

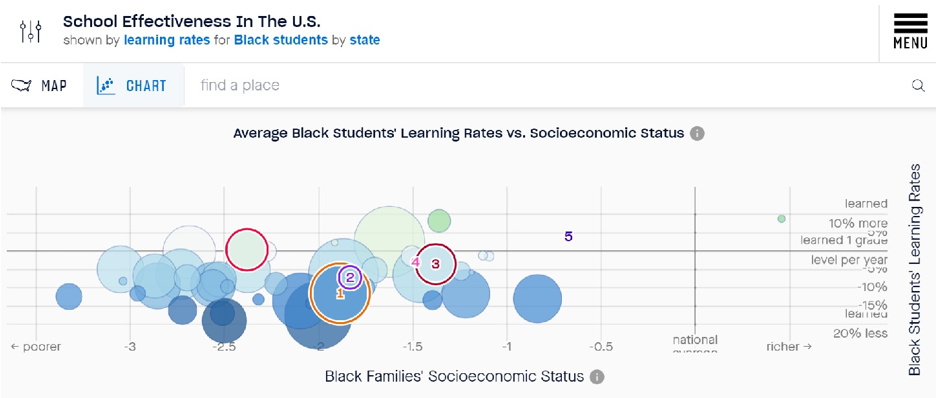

The Wired article contains a point-counterpoint between a representative of the American Association of Superintendents and the Black Family Homeschool Educators and Scholars. The Superintendent’s representative makes the usual worried statements about money for the system. The Black homeschool advocate seems much more focused on the interests of students:

… Ali-Coleman, of Black Family Homeschool Educators and Scholars, warns against over-emphasizing the limitations of low-income families. She says that not all homeschooling families are necessarily financially privileged, either, pointing to Fields-Smith’s research on single Black mothers who homeschool their kids in spite of low-income status.

Moreover, adequately funded public school systems can still harm children of color: More money won’t shield a child from unequal discipline, a biased curriculum, or a pervasive school-to-prison pipeline that disproportionately pushes Black youth out of schools and into criminal justice systems.

Sure enough, when you plot academic growth for Black students in the top five spending states – in order, New York (1); Connecticut (2); New Jersey (3); Vermont (4); and Alaska (5) – in the Opportunity Project at Stanford University explorer, only Alaska has a rate at or above the national average.

Of greater interest still will be Tyton Partners’ estimated 7 million students who engaged in supplemental pods. These students remained enrolled in another school online but joined small education communities to do so.

The Tyton Partners survey found 15% of parents made shifts in their child’s schooling situation this past fall. More change is likely on the way for this fall. In the medium to long term, the most significant change likely will be the availability of entirely new sectors and methods of education.

BB International School in Pompano Beach, Florida, is an example of how education choice opens the door to more fun and less bureaucracy. Here, first- and second-graders in Alexa Altamura’s class mix academics with enrichment.

What teachers need are PODS (All together now!)

Teachers want those PODS! (Everybody)

Teachers love those PODS, PODS,

PODS are what they need (PODS are what they need)

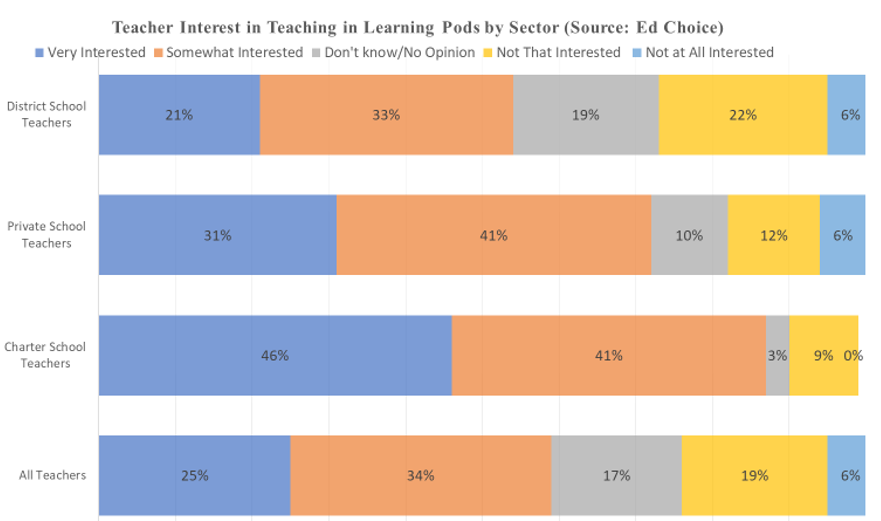

Okay, so now that I’ve got a song stuck in your head for the rest of the day (week?) let’s discuss an EdChoice survey that shows teachers love learning pods. And that includes teachers from every K-12 sector:

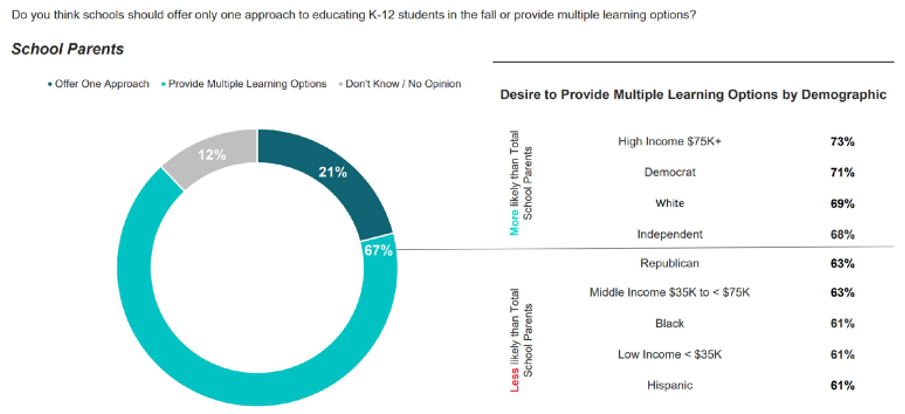

The research shows some 87% of charter school teachers are either “very interested” or “somewhat interested” in teaching in a learning pod; 59% of all teachers are interested. Schools just might want to find a way to give teachers what they want, especially given the fact that the same survey shows families also want multiple options for their children this fall:

The research shows some 87% of charter school teachers are either “very interested” or “somewhat interested” in teaching in a learning pod; 59% of all teachers are interested. Schools just might want to find a way to give teachers what they want, especially given the fact that the same survey shows families also want multiple options for their children this fall:

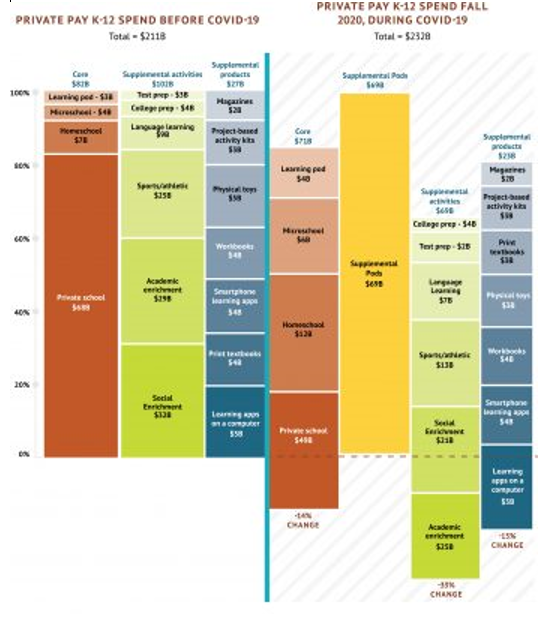

Oh, and then there is the new Tyton Partners survey showing that families dropped more of their own money on learning pods last fall than on private school tuition:

Oh, and then there is the new Tyton Partners survey showing that families dropped more of their own money on learning pods last fall than on private school tuition:

It would be interesting to survey former teachers on what they think of pods. Every state has a large pool of experienced teachers, many of whom tapped out of the profession in frustration of various sorts. Could they be tempted back into the teaching profession by new school models with more fun and less bureaucracy?

It would be interesting to survey former teachers on what they think of pods. Every state has a large pool of experienced teachers, many of whom tapped out of the profession in frustration of various sorts. Could they be tempted back into the teaching profession by new school models with more fun and less bureaucracy?

I’d love to find out, because we need all the effective teachers we can get.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jude Schwallbach, research associate and project coordinator at The Heritage Foundation, originally appeared in The Daily Signal.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jude Schwallbach, research associate and project coordinator at The Heritage Foundation, originally appeared in The Daily Signal.

National School Choice Week has taken on renewed importance this year, as too many families are approaching the one-year mark of crisis online learning provided by their public school district.

National School Choice Week has taken on renewed importance this year, as too many families are approaching the one-year mark of crisis online learning provided by their public school district.

Last March, the coronavirus pandemic shuttered schools nationwide, forcing teachers, parents, and students to transition to virtual classrooms and grapple with the various effects of lockdowns. Ten months later, parents report that 53% of K-12 students are still learning in their virtual classrooms.

Public schools have remained largely closed to in-person instruction.

Recent research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that in-person learning is rarely a source of large outbreak. Even though in-person learning is one of the safest activities for children, proposals to reopen district schools for face-to-face learning have met with staunch opposition from teachers’ unions.

Inexplicably, teachers unions have also rejected measures which would require teachers to be more available to students throughout the day via live video.

The Center on Reinventing Public Education’s director, Robin Lake, told the New York Times that the teachers unions’ vacillating responses feel “like we are treating kids as pawns in this game.”

Adding to parents’ frustrations, teachers unions have also taken the opportunity to push for a whole host of concessions that have nothing to do with health safety.

For instance, the American Federation of Teachers has a long list of demands, including: additional food programs, guidance counselors, smaller classes, tutors to assist teachers, and “culturally responsive practices.”

Similarly, The United Teachers of Los Angeles has demanded a moratorium on charter schools, higher taxes for the wealthy, and “Medicare for All.”

The blatant, non-pandemic-related demands of many teachers unions have illustrated what Stanford University professor Terry Moe noted a decade ago: “This is a school system organized for the benefit of the people who work in it, not for the kids they are expected to teach.”

The inflexibility of teachers unions has increasingly become a source of escalating tension with local officials. For example, Chicago Public Schools, the third largest school district in the nation, locked teachers out of their virtual classrooms after they refused to return to in-person instruction with classrooms at less than 20% capacity.

Such unbending posture has provoked the ire of parents and left many children frustrated, both academically and socially. As Tim Carne wrote in the Washington Examiner, “The very people who have most loudly declared the importance of public schools now are deliberately destroying public schools.”

Many parents are tired of being strong-armed by teachers unions and have pursued alternative education options for their children.

For instance, the learning pod phenomenon, wherein parents work together to pool resources and hire their own tutors and materials is popular. This allows students to return to in-person lessons, even if school districts refuse to reopen.

Last September, a national poll by the pro-school choice nonprofit EdChoice indicated that 18% of surveyed parents were looking to join one. At the same time, 70% of surveyed teachers reported interest in teaching in a pod.

A recent report by education scholars Michael B. Henderson, Paul Peterson, and Martin West found that approximately 3 million students—nearly 6% of K-12 students—currently participate in a learning pod.

Notably, pod participants are more likely to be “from families in the bottom quartile of the income distribution.” The authors wrote, “Parent reports suggest that 9% of all students from low-income families and 5% of all students from high-income families are participating in pods.”

Families have embraced private school options, too. A survey last November of 160 schools in 15 states and Washington, D.C., showed that half of the surveyed private schools experienced higher enrollment this academic year than they had the previous year pre-pandemic.

Moreover, more than 75% of surveyed private schools were open for in-person instruction. The remaining schools offered hybrid education, which is a combination of in-person and virtual learning.

Children could have greater access to private education if more states made education dollars student-centered. For instance, parent controlled education savings accounts allow parents to spend their funds on approved education costs, like private tutoring, books, or tuition. These accounts already exist in five states.

National School Choice Week is an important reminder that “public education” means education available to the public, regardless of the type of school it takes place in. It is the perfect time to remember that parents, not teachers unions, are best positioned to determine the education needs of children.

School choice options like education savings accounts can bring education consistency to families across the country during a most uncertain time. National School Choice Week is an important reminder of that.