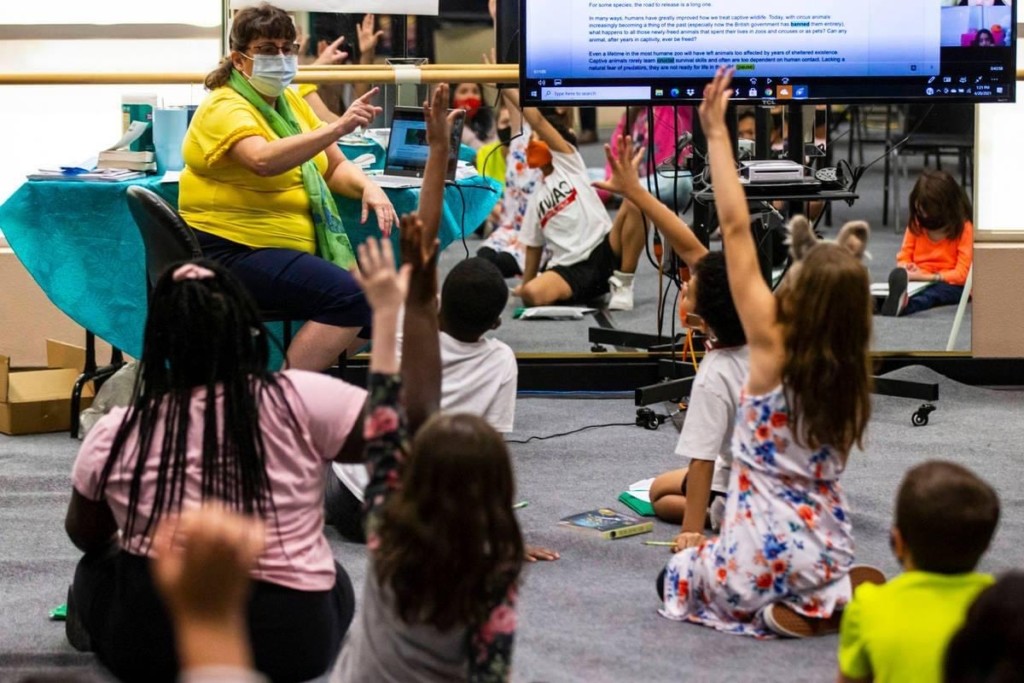

Christy Kian of Boca Raton discovered a new way to pursue her passion for teaching during the coronavirus shutdown.

Editor's note: reimaginED is proud to reintroduce to our readers our best content of 2021 such as this feature story from senior writer Lisa Buie.

Christy Kian wasn’t sure what she was getting into last year when she agreed to help a parent struggling to educate her two children during the coronavirus pandemic.

Christy Kian wasn’t sure what she was getting into last year when she agreed to help a parent struggling to educate her two children during the coronavirus pandemic.

The mom wasn’t satisfied with the distance learning plan her school had set up at the start of the shutdown, and things were still in flux for the coming school year. She asked Kian if she would be willing to teach her children at their home.

After nearly two decades of experience in traditional school settings, Kian had to think carefully. But in the end, the call to set off on a new adventure proved too tempting.

Those tentative steps into the unknown launched Kian’s tutoring business.

“It’s been magical,” said Kian, whose Boca Raton-based company, Launch Concierge Learning LLC, blasted off in mid-July. “It’s been better than I could have imagined.”

Kian spent the 2020-21 school year working exclusively with two pandemic pods, small groups that employ a teacher to instruct children in person at home. The pods became a national phenomenon last summer when school campuses in some states refused or were forbidden to reopen, spurring some parents to take matters into their own hands.

Within weeks, social media sites popped up across the country, matching teachers with families eager to try something new. Some families grouped to form micro-schools, which typically serve fewer than 10 students.

The Washington Post called the pods “the 2020 version of the one-room schoolhouse, privately funded.” Experts wrote essays and did research on the trend.

To prepare for her new adventure, Kian spent the summer of 2020 creating curriculum, designing lesson plans, and setting everything up on a spread sheet so that everything would run smoothly from Day 1.

She made the decision to teach the children mostly in person, with kindergarteners in one group and second graders in another. When one family traveled briefly out of state, she pivoted and taught them online.

All her students have thrived under the new learning model.

“I’m doing fractions in my kindergarten,” she said. “If you look at the regular curriculum for kindergarten, fractions are not a part of it.”

The students made such learning gains that Kian decided to introduce them to material early in hopes of giving them an edge when they return to the traditional classroom.

“By exposing them to it now, I hope it will kick in later,” she said.

A peek at her Facebook page offers a window into the classroom.

“Insect week! This Eastern Lubber Grasshopper was a wonderful sport in class. Now she is free again in my backyard. But not before teaching us to sing Head, Thorax, Abdomen.”

“Insect week! This Eastern Lubber Grasshopper was a wonderful sport in class. Now she is free again in my backyard. But not before teaching us to sing Head, Thorax, Abdomen.”

“Our second-graders wrote their own fairy tales!”

The students learned about scientists such as Jonas Salk and artists such as Claude Monet, experimented with stop motion animation, and read lots of books. Kian made so many trips to the public library that the staff came to know her by name.

Just before winter break, the students surprised Kian with a T-shirt with her logo – a rocket ship blasting off – on the front and “Commander Christy” emblazoned on the back. They all wore T-shirts that matched.

The show of school spirit touched her.

“It really felt wonderful to me that they took such ownership,” she said.

With the kindergarteners heading back to the traditional classroom in the fall, as their parents had planned from the start, Kian is focusing on her rising third graders, who will be returning to her for another year. She’ll spend this summer creating curriculum and lesson plans for them.

She also is considering picking up another group for fall but still hasn’t decided. In any case, she has no plans to return to traditional school.

Quoting a parent, she said, “This has been a terrible year, but we made lemonade.”

Editor’s note: This post from Bruno V. Manno, senior adviser to the Walton Family Foundation’s K-12 Program and a redefinED contributor, appeared Tuesday on The 74. Manno references Florida Virtual School, which saw a 57% increase in new course enrollments in its part-time Flex program, in his discussion of how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the face of K-12 education.

Editor’s note: This post from Bruno V. Manno, senior adviser to the Walton Family Foundation’s K-12 Program and a redefinED contributor, appeared Tuesday on The 74. Manno references Florida Virtual School, which saw a 57% increase in new course enrollments in its part-time Flex program, in his discussion of how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the face of K-12 education.

“Never in my lifetime have so many parents been so eager for so much education change.”

So said longtime pollster Frank Luntz after surveying 1,000 public and private school parents on how the pandemic affected their view of schools.

COVID-19 forced schools to change from being buildings where teaching, learning and programs were bundled together to serve students and families to a menu of services and choices that parents were forced to piece together — rebundle — to meet their needs.

The potential long-term result could be a more student-focused, parent-directed and pluralistic K-12 school system.

The consulting firm Tyton Partners estimates COVID-19 shock produced a 2.6 million-student decrease in district and private schools, with charter schools, homeschooling, micro-schools and other alternatives gaining enrollment. The U.S. Census reports homeschooling enrollment increased from 5.4 to 11.1 percent of households. African Americans registered a fivefold increase, from 3.3 to 16.1 percent.

What other alternatives did parents choose as they worked to rebuild their child’s schooling?

One was family-organized discovery sites, aka pods — gathering small groups of students, in person or virtually, with added services like tutoring, childcare or afterschool programs. San Francisco Mayor London Breed opened 84 pods serving around 2,400 children, about 96 percent racial minorities.

The Columbus, Ohio, YMCA offered pods for students aged 5 to 16 attending schools virtually, with arrival as early as 6 a.m. JPMorgan Chase offered discounts on virtual tutors and pods for eligible employees using Bright Horizons, its employer provider, and opened its 14 childcare centers for employees’ children’s remote learning at no cost. Organizations like SchoolHouse, LearningPodsHub and Selected for Families helped parents start pods, organizing teachers and tutors.

To continue reading, click here.

Every child at Southern Nevada Urban Micro Academy made at least one full year’s academic growth in reading/English language arts in 2020-21 despite the fact that three out of four arrived at the start of the year at least two grade levels behind.

Editor’s note: This commentary is from Don Soifer, president of Nevada Action for School Options and a founding leader of the Southern Nevada Urban Micro Academy. To learn more about the academy, watch this short documentary video.

Ten miles north of the bright lights of the Las Vegas strip, one of the nation’s more powerful beacons for the future of schooling completed its first academic year in comparably stunning fashion.

The Southern Nevada Urban Micro Academy (SNUMA), the first-of-its-kind public private partnership micro-school designed to tackle pandemic learning loss, has operated in person every school day. Clark County public schools, meanwhile, operated a distance-learning program that few felt was working close to optimally.

While the most recent school year surely will prove unforgettable for any number of reasons related to hardship, challenge, and tragic loss, the experience of the nearly 100 SNUMA learners and their families were overwhelmingly positive, and in sharp contrast with most of their prior schooling experience.

North Las Vegas is one of Nevada’s poorest and fastest-growing cities. Residents and the public officials who serve them have complained for decades about being underserved by their massive school district, the fifth largest in the nation. Three out of four children who attended SNUMA last year arrived at the start of the year and six months into the pandemic at least two grade levels behind in their mastery of English language arts and math.

So, it was even more valuable when 100% of SNUMA students made at least one full year’s academic growth during the year in reading/English language arts, and 87% posted at least two years’ growth.

The results in math were comparable, if slightly muted; 92% finished the year having accomplished at least one school year’s academic growth in math, and 35% completed at least two years of academic growth.

The most striking results came from the program’s third and fourth grades. Every one of them who attended for the full year accomplished at least two years of academic growth in English language arts. In math, all accomplished at least one full year’s academic math growth, and 75% completed at least two years of math growth.

The most striking results came from the program’s third and fourth grades. Every one of them who attended for the full year accomplished at least two years of academic growth in English language arts. In math, all accomplished at least one full year’s academic math growth, and 75% completed at least two years of math growth.

The Micro Academy doubled the size of its student population prior to the spring semester, and its midyear cohort of children followed a comparable trajectory of learning growth. All children arriving midyear achieved a full year’s growth in English, and more than half did so in math.

SNUMA’s highly structured daily schedules emphasized academics using a personalized learning model that combined strengths of world-class digital learning tools with those of a rich, in-person learning experience that embraced whole-group, small-group and one-on-one instruction from a team of “learning guides” and interventionists.

The nonprofit in charge of the school’s academics worked with an all-star team of partners to deliver its high-quality product, including grades 3-8 curriculum provider Cadence Learning, whose unique model provided professional development and support described by the micro-school's educators as some of the best they had ever received.

The City of North Las Vegas funded the micro-schools entirely out of municipal funds, not per-pupil school funding, for its residents and for children of emergency workers serving the city. Children attended at a small cost, $2 per day, for the first semester, and entirely for free for the second semester. To attend SNUMA, all children were registered as homeschoolers.

The city contracted with nonprofit Nevada Action for School Options to provide the teaching and learning for SNUMA. The model truly is an active partnership, located in the city’s two recreation centers and a library, with free breakfast and lunch provided for all children. Small class sizes characterize SNUMA’s learning environment, and the 15-child classroom limit proved not only valuable for both pandemic safety and education reasons, but quite popular with families who had been accustomed to a school district known for large and even overcrowded classrooms.

The forward-focused city leadership, at the time all elected Democrats, wanted to serve its children well while working to get parents back to work. Offering a desirable alternative to “leaving their child home alone with a jar of peanut butter” was an early motivation.

Councilwoman Pamela Goynes-Brown, a retired educator and one of the program’s primary champions, described SNUMA as “micro-schooling to make the powerless powerful.” She worked with the micro-school’s leadership team to create a model with equitable and measurable impacts.

On this episode, redefinED’s executive editor speaks to a leader in the charter school organization about the exploding demand for its classical liberal arts education. Currently serving more than 20,000 students in brick-and-mortar classrooms in Arizona and Texas, Great Hearts Online launched in August because of the COVID-19 pandemic and currently serves approximately 1,000 students across both states.

On this episode, redefinED’s executive editor speaks to a leader in the charter school organization about the exploding demand for its classical liberal arts education. Currently serving more than 20,000 students in brick-and-mortar classrooms in Arizona and Texas, Great Hearts Online launched in August because of the COVID-19 pandemic and currently serves approximately 1,000 students across both states.

The two discuss the perils of emergency online learning, which Indorf refers to as potentially “lonely, procedural, and uninspiring.” They also discuss how Great Hearts works directly with its families early in the school design process to create a learning environment that best fits their needs, and Great Hearts’ upcoming plans for pods and micro-schools.

“There's been a lot of work to create virtual and in-person community and to teach students how to build healthy relationships in each ... That's an important part of becoming literate and healthy in our technology-enhanced world."

EPISODE DETAILS:

· Great Hearts’ commitment to fostering robust online and in-person communities for its families

· The pivot from temporarily online schooling to a robust full-time program for families who want it

· How families are involved in the development of Great Hearts’ programs

· Plans for expansion beyond Arizona and Texas and pods and micro-schools supported by Great Hearts Online

Verdi EcoSchool and EcoHigh's place-based education philosophy envisions the immediate environment as the student's most important classroom.

Like most great ideas, this one started on the ground, with a handful of eighth graders.

After spending middle school in a unique environment that has earned the reputation of being the Southeast’s first urban farm school, the teens were unwilling to trade the lush gardens of the Melbourne Eau Gallie Arts District for the vanilla hallways of a traditional high school.

They asked: Would Ayana and John Verdi, founders of Verdi EcoSchool, consider adding a high school to their K-8 treasure?

Ayana initially dismissed the idea, calling it “a whole new stratosphere of education” she was not prepared to explore.

But the students persisted. They won support from their parents and organized a presentation. Their enthusiasm, combined with the Verdis’ entrepreneurial spirit, ultimately influenced the couple’s decision to give it a try. School staff and students then organized a meeting to sell the project to the community.

“We talked about why continuing into high school with a passion-based learning approach that’s student-driven in a community that we use as our campus was vital for current and future families,” Ayana recalled.

Using the local community as a classroom creates an immersive curriculum that underscores Verdi EcoHigh's place-based education philosophy.

Their pitch won over local leaders. In 2020, Verdi EcoHigh opened its doors to students in grades 9 through 12. But the key piece to making EcoHigh a reality came from the Drexel Fund, a national nonprofit foundation that provides financial support and mentoring to educational entrepreneurs seeking to launch and scale pioneering private schools focused on underserved communities.

The organization awarded Verdi EcoSchool a fellowship package worth $100,000.

“Ayana had an exciting K-8, but she wanted to open a high school for it,” said John Eriksen, Drexel co-founder and managing partner. “We look for interesting and diverse models of schools, and we couldn’t find anything like that anywhere in the country.”

Drexel’s mission to kickstart private schools accessible to all socio-economic groups makes focusing on states with robust education school choice policies like Florida’s a natural fit, Eriksen said. About 60% of Drexel applications come from the Sunshine State.

Other schools the fund has assisted in Florida include Cristo Rey in Tampa and the three Academy Prep Centers for Education in the Tampa Bay area and Lakeland. A more recent project is SailFuture Academy, a St. Petersburg foster care agency that is opening a vocational high school this fall for lower-income and at-risk teens who have become disengaged in traditional high school settings.

“The Drexel Fund provided me with an incredible network of school leaders who could help to offer guidance and tangible resources as I worked to implement the EcoHigh vision,” Ayana said.

The fund picked up Ayana’s travel costs to visit trailblazing public, private and charter schools across the nation so she could learn best practices when launching EcoHigh. She also received a consultation with Darren Jackson, Drexel Fund board member and former CFO of Best Buy and Nordstrom.

Most import, Ayana said, the Drexel Fund offered the power of reinforcement through their recognition of her hard work to become a school of innovation.

About one-third of the students who attend the Verdis' school use state choice scholarships.

“At the end of my fellowship year, I was given the opportunity to present my plan for a new place and project-based high school and received a grant to support the creation of EcoHigh and the potential for continued partnership with the Drexel Fund through replication support,” she said.

EcoHigh offers three tracks: sustainability studies, agricultural science, and agri-business. The program is place- and program-based, meaning that learning happens in many places and many ways. At this unique high school, one of the places learning takes place is the Brevard Zoo.

A partnership with the zoo allows high schoolers to spend three days a week there, where they learn, design and work on the campus. The other two days are spent at the main campus in the Eau Gallie Arts District, where the students learn in nature and work on community improvement projects.

Tuition at the 77-student school is $9,350 annually. The school accepts the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship and the Family Empowerment Scholarship, for which about one-third of the students qualify.

Ayana said she hopes to continue to grow the school, which offers full-time and part-time education as well as enrichment opportunities for homeschool students. The Drexel Fund has pledged to be there for her when the time comes to expand, as it stands with all innovative school leaders who have a desire to help underserved students.

“They bring us the innovation and diversity,” he said. “We help them pressure-test their ideas.”

Eriksen said some ideas, which involve micro-schools or pods, “we can’t touch right now in Florida” because the state relies heavily on a traditional school education model. If the Florida Legislature chooses to expand education savings accounts or make other tweaks to existing law, those changes could make Florida, already hospitable to choice, an even more fertile ground for innovation.

“If Florida went for a more personalized model,” Erickson said, “the amount of investment would be incredible.”

On this episode, Tuthill speaks with the co-owner of SchoolHouse, an organization serving several hundred students in eight states by creating flexible learning communities known as micro-pods for four to eight students.

On this episode, Tuthill speaks with the co-owner of SchoolHouse, an organization serving several hundred students in eight states by creating flexible learning communities known as micro-pods for four to eight students.

Tuthill and Connor discuss how SchoolHouse connects members of the community with a shared interest in a smaller learning environment to each other, allowing families to customize their learning pod from the ground up. The two also discuss how micro-schools empower teachers as well as students, and how education savings accounts of the type proposed in Florida’s Senate Bill 48 could help more families access smaller, more customized educational options.

"What excites me about ESAs is that it's really what parents already do, and the government is responding to that. I don’t know a single parent ... who doesn’t pick from different vendors for different things ... (parents) have choice in their lives, and it's giving them the money to really fund that, which is exciting."

EPISODE DETAILS:

· Connor’s background as an educator and education law attorney

· The creation of SchoolHouse, how it works, and how the pandemic accelerated the micro-school learning trend

· Opportunities for teachers to thrive in the customized learning environment of micro-schools

· Creating greater equity for serving families without financial means through ESAs

On this episode, Tuthill catches up with the founder and CEO of Arizona-based Prenda, an organization on the front lines of the micro-school tsunami that has soared during the global pandemic.

On this episode, Tuthill catches up with the founder and CEO of Arizona-based Prenda, an organization on the front lines of the micro-school tsunami that has soared during the global pandemic.

Smith describes how these home-learning environments, catering to fewer than a dozen similarly aged students, are gaining traction among families looking for creative education options. Amidst rampant uncertainty and accelerated changes to public education, micro-schools and other smaller “pod” education formations are sweeping the country – and blending mastery-based education with peer collaboration.

Smith discusses Prenda’s expansion into Colorado and his team’s experiences in working with partners to bring micro-schools to as many communities as possible, noting he’s inspired by those in district schools who see the importance of adding micro-schools to their portfolio of options. He believes there are passionate visionaries and leaders working inside traditional systems, stepping up and taking risks against the wishes of institutional pushback.

"The genie is out of the bottle (on micro-schools) ... Families are reporting their child is engaged, and the format really works ... A safe comfortable environment right in the neighborhood can be empowering and kids can come out of their shell.”

EPISODE DETAILS:

· Prenda’s most recent year and lessons learned during the pandemic

· Assuaging parents’ fears about shifting from factory-model education and toward intrinsic, organic learning

· The regulatory environment in particular states and Prenda’s plan for expansion

· How school districts have stepped up to encourage micro-schools

· The challenges that lie ahead

To listen to Tuthill’s earlier podcast with Smith, click HERE.

Recently, we reported on the city of North Las Vegas’ pandemic pod effort, namely, the Southern Nevada Urban Mico Academy, or SNUMA. Included was what must be the edu-quote of the year from North Las Vegas Mayor John Lee:

Recently, we reported on the city of North Las Vegas’ pandemic pod effort, namely, the Southern Nevada Urban Mico Academy, or SNUMA. Included was what must be the edu-quote of the year from North Las Vegas Mayor John Lee:

Children who otherwise likely would be given a jar of peanut butter and told not to answer the door while their parents work and CCSD remains virtual instead are attending in-person homeschool co-op learning sessions, receiving live tutoring and participating in enriching, fun activities in a safe, socially distant environment at a cost of just $2 per day.

Now comes word not only that the city is renewing the effort until the end of spring semester 2021, but of preliminary data on academic outcomes.

Says councilwoman Pamela Goynes-Brown, who has led the city’s efforts at SNUMA: “Our kids are learning and thriving in a safe environment. I could not be more proud of their progress.”

Among the academy’s academic results:

· While 78% of children arrived at SNUMA below grade level in reading, 62% are now at or above grade level

· While 93% of children arrived at SNUMA below grade level in math, 100% currently are working on material that is at least on grade level

· While nearly three-quarters of third graders (71%) arrived reading below grade level, 42% are now at grade level, and 28% are above grade level; additionally, 85% have completed at least a year's worth of growth since their initial assessment

· While 71% of third graders were testing below grade level in math, 57% are now working at grade level, and 43% are working above grade level

The news story lacks detail regarding testing, but these data presumably have been derived from formative assessments. The data appear very promising, but obviously a great deal more study is warranted before drawing any conclusions. Nevertheless, beating the living daylights out of being left alone with a jar of peanut butter may just be a warmup for this innovative form of education, so stay tuned to this channel for more developments in 2021.

Music producer DJ Khaled with his children, Asahd, 4, and Aalam, 10 months

DJ Khaled, who has produced 18 Top 40 hits and eight Top 10 albums, earned a feature in the Dec. 2 issue of People magazine for starting a pandemic pod for his 4-year-old son and his son’s classmates.

“In March, when Asahd's preschool sent everybody home, I was doing the Zoom classes with him every single day,” the article quotes Khaled’s wife, Nicole Tuck. “I thought to myself, 'This cannot be the best we can do!’ So, I organized a learning pod at our house with other quarantined families. We have seven kids and two teachers, and it's absolutely amazing.”

Having a seven-child school with two teachers in a guest house may strike some as being a bit out of reach of the average American family. Phillip II of Macedon created a one-to-one pod for his son with Aristotle, and that worked out great for Alexander, but alas, it isn’t easily replicated. Public policy, however, can make education like Khaled and Tuck are providing broadly available.

Many families would struggle to hire one, much less two teachers, using their own funds. But in Arizona, micro-school genius Prenda partners with districts, charters and families who use education savings accounts to form micro-school communities. When the pandemic hit, 700 students were learning through Prenda, but in the ensuing months, that number has greatly increased.

District, charter and ESA enrollment allows students to access their K-12 funds to pay an in-person guide and provide both in-person and distance learning. A growing number of school districts, cities and philanthropies have been helping to create small learning communities around the country as well. The Center for the Reinvention of Public Education has started keeping a tally of these efforts, which you can view here.

Khaled is hardly alone in his enthusiasm for micro-schools. A recent survey of parents conducted by Ed Choice found that 35% were participating in a pod; another 18% reported interest in either joining or forming a pod. Meanwhile, a recent parent poll conducted by the National Parents Union found almost two-thirds of those surveyed said they want schools to focus on new ways to teach children as a result of COVID-19 as opposed 32% who said they want schools to get back to normal as quickly as possible. Fifty-eight percent said they want schools to continue to provide online options for students post-pandemic.

Hayley Lewis, a former public school teacher, wrote an important piece called, “Why I quit teaching in the public school system (it wasn’t just COVID).”

Hayley Lewis, a former public school teacher, wrote an important piece called, “Why I quit teaching in the public school system (it wasn’t just COVID).”

Here is an excerpt:

The American public-school system is beyond repair. I honestly don’t know where you even begin attempting to fix a system that’s so systematically flawed. Policies are made by those who haven’t been in a classroom in years, if at all, and show the extreme disconnect between the theoretical and the everyday reality that is the life of a teacher and their students.

The chances of having a high-quality curriculum are next to nothing, and if you’re lucky enough to have something that’s worthwhile, there are so many other hoops to jump through and issues that arise, it makes it virtually impossible to teach effectively and to truly prioritize the learning of children.

The quality of public education, like anything, varies widely. Many of the most dedicated and successful, and yes, even the most innovative educators I have had the pleasure of meeting, work in the district system. Like anything with widely varying quality the well-to-do tend to get the better part of it, and the poor the worst. That’s why it is vital to address equity concerns in the design of choice programs.

The “better part of” something, however, doesn’t ensure that it is actually high quality. You should read Lewis’ entire piece, but in essence, she describes a work environment in which high-quality instruction happens in only limited spurts and even then, despite the system rather than because of it.

Large numbers of students in classrooms make it nearly impossible to provide differentiated instruction — the quantity of children is just too high to get to in a day. Teaching five subjects to 30 different children, all with varying levels and learning styles is nearly impossible in a perfect world scenario.

But throw in classroom management, heightened behavior issues, standardized assessments and other requirements that have no immediate impact on real learning, and the chance of truly meeting the unique needs of a diverse group of students is next to nothing.

What to do about this? How about starting over, as BBI International, a micro-school in Pompano Beach, Florida, did. You can read the details here.

The BBI International micro school is another example of what's possible with the expansion of private school choice.

Teaching five subjects to 30 different children, all with varying levels and learning styles, as Lewis described it, may be a task enhanced by technology, while the application of knowledge occurs in small in-person learning communities. Large elements of a high-quality curriculum can be delivered live by a single digital faculty, while in-person instructors lead a related set of student projects – science experiments, theatrical productions, student debates and much more.

Rather than remaining an airy dream, innovative educators currently are educating students in this fashion, and the demand is growing.

If you want a spot in the legacy system Lewis describes, it will always be available to you. It takes a system of millions to hold teachers like Hayley Lewis back. The funding for that system is guaranteed in state constitutions. It’s a system well designed to maximize adult employment, including lots of people who make it next to impossible for dedicated people like Lewis to do their jobs.

The system is, alas, poorly designed to deliver education to children. Having experienced the inability to serve from within dysfunction, Lewis concludes:

I’m not sure where this new path will take me, but I know that I have a duty to make this world a better place, and that was not happening where I was before. It’s my deepest hope that I can pave a new way and be an example to future educators, showing them that it’s ultimately worth the sacrifice to give children the quality education and love they all deserve.

The kids still need you, Ms. Lewis, and a system worthier of your dedication is being constructed. I hope you’ll be among those to mold the future to decide the shape of things to come.