Providence Hybrid Academy, serving Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, offers outdoor play, meaningful friendships, and a supportive community of like-minded parents influenced by the work of Charlotte Mason, a 19th century British educator and strong Christian believer.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Colleen Hroncich, a policy analyst at the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, and Sharon Sedlar, founder and president of PA Families for Education Choice, appeared last week on realclearpennsylvania.com.

Enrollment in Pennsylvania district schools has fallen slightly more than 3% since 2019-20 – a drop of nearly 51,000 students. At the same time, homeschooling and private school enrollment have risen 53% and 5%, respectively.

There has clearly been an uptick in parents selecting options beyond their local district school, and the trends don’t show any signs of slowing as another school year wraps up.

Two increasingly popular options are microschools and hybrid schools. Unfortunately, these are often choices that seem foreign and complicated to many parents, keeping families who would likely thrive in one of these options from taking the leap.

The models don’t necessarily have strict definitions, and the terms aren’t mutually exclusive. A microschool can be a hybrid school, and vice versa. All of this can add to the confusion for parents exploring their options.

Microschools, as the name implies, are small – sometimes consisting of fewer than 10 children in a close age range. A larger microschool might serve 100 or so students in small, multiage groups, like ages 7-9, 10-13, and so on.

Microschools often place students based on where they currently are in a subject area rather than relying solely on their age. They also tend to be more student-directed compared to a conventional classroom, with learning coaches, tutors, or guides there to help the kids learn. There may or may not be a formal curriculum.

Hybrid schools utilize a combination of at-school and at-home learning, but there can be much variety in how they are structured. Students may meet in person two days and learn at home three days, or the other way around. Some hybrids meet half days in person, while the rest of the time is spent at home.

Parents, students, and teachers often call it the “best of both worlds,” as their children get the support of in-person instruction and the flexibility of homeschooling. No wonder recent polling shows 55% of Pennsylvania parents are interested in some level of hybrid schooling.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Colleen Hroncich, a policy analyst with Cato's Center for Educational Freedom, appeared Sunday on the center's website.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Colleen Hroncich, a policy analyst with Cato's Center for Educational Freedom, appeared Sunday on the center's website.

My oldest child is graduating from college tomorrow, so it has me thinking about our educational journey—which could best be described as eclectic. At various times, we used private school, district school, and cyber charter school. But we ultimately landed on homeschooling.

That doesn’t mean they were literally learning at home every day. My kids participated in co‐ops, hybrid classes, dual enrollment, athletics, and more. This gave them access to experts and plenty of social time.

It can be scary taking charge of your children’s education—I remember feeling very relieved when my oldest received her first college acceptance. But today there are more resources than you can imagine to help you create the best education plan for your children’s individual needs and interests. And with the growth of education entrepreneurship, the situation is getting even better.

For starters, you don’t have to go it alone. The growth of microschools and hybrid schools means there are flexible learning options in many areas that previously had none. One goal of the Friday Feature is to help parents see the diversity of educational options that exist. To see what’s available in your area, you can search online, check with friends and neighbors, or connect with a local homeschool group.

If you don’t find what you’re looking for, the good news is that there’s also more support for people looking to start new learning entities.

The National Microschooling Center is a great starting place if you’re considering creating your own microschool. The National Hybrid Schools Project at Kennesaw State University is also a tremendous resource. There are businesses—like Microschool Builders and Teacher, Let Your Light Shine—whose focus is helping people navigate the path to education entrepreneurship. And grant opportunities, like VELA and Yass Prize, can help with funding.

We were fortunate to be in an area with a strong homeschool community and therefore had plenty of activities to choose from. But I’m still a bit jealous when I speak to parents and teachers each week and hear about the amazing educational environments they’ve created.

There’s also an abundance of online resources available, from full online schools to à la carte classes in every subject imaginable. If you like online classes but want an in‐person component, KaiPod Learning might be just the ticket. These are flexible learning centers where kids can bring whatever curriculum they’re using and work with support from a KaiPod learning coach. There are daily enrichment activities, like art, music, and coding, as well as social time.

One of the best parts of taking charge of your children’s education is that it puts you in the driver’s seat. If your children are advanced in particular subjects, they can push forward at their own pace. In areas where they struggle, they can take their time and be sure they understand before moving ahead. (One potential downside is that this takes extra discipline and can be challenging. But it’s tremendously beneficial overall.)

These nonconventional learning paths can be great for kids who don’t want to go to college, too. Flexible schedules free up time to pursue a trade, music, performing arts, sports, agriculture, and more. As kids get older, they can increasingly take charge of their own education. This lends itself to developing an entrepreneurial outlook, which is vitally important in a world where technology and public policy are constantly changing the workforce and economic landscapes.

“One size doesn’t fit all” is a common saying among school choice supporters. But this is more than just a slogan. It’s an acknowledgement that children are unique and should have access to learning environments that work for them. Public policy is catching up to this understanding—six states have passed some version of a universal education savings account that will let parents fund multiple education options.

If you’ve considered taking the reins when it comes to your children’s education, it’s a great time to act on it. Whether you choose a full‐time, in‐person option, a hybrid schedule, or full homeschooling, you’ll be able to customize a learning plan that works best for your kids and your family.

And you may even become an education entrepreneur yourself and end up with a fulfilling career that you never expected.

The VELA Foundation offers Bramblewood Academy, a hybrid co-op located on a farm in Hilltown, Pennsylvania, as an example of “unconventional education.” Bramblewood offers a mix of project-based learning, Socratic discussions, and real-world activities, maintaining flexibility with programs that run from two to five days a week. Parents are not expected to be teachers, but they are encouraged to volunteer to receive a nearly 50% tuition discount.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Bruno V. Manno, senior advisor for the Walton Family Foundation education program, is an exclusive to reimaginED. The Foundation provides support to VELA Education Fund, mentioned in this piece.

Many stories about COVID-19 describe its damaging effects on K-12 education, from closing schools to enrollment declines to student emotional problems and learning loss. These stories are true and should be told.

But so should another group of stories -- hopeful ones -- that describe how K-12 civic entrepreneurs in America’s communities are creating new learning opportunities for families and their children. These everyday grassroots entrepreneurs are creating a new unconventional K-12 education sector through permissionless innovation.

Here are three features of that approach.

First, these entrepreneurs want to change things, and, typically, do not ask permission from regulatory agencies to start their ventures. When they deal with bureaucracy, they curb its suffocating effects.

Second, families enroll their children in these innovative programs because they are accommodating and meeting the new learning needs of families following the pandemic.

Third, these entrepreneurs believe their ventures are adding unique value to people’s lives by creating what I call a new K-12 sector of unconventional learning opportunities. Their programs are flexible and tailored to student needs compared to the traditional K-12 system.

In short, the maxim of these K-12 civic entrepreneurs goes something like this: “Just do it. They will come. And together, we can create something new and valuable.”

A recent report from VELA Education Fund describes these new ventures. It is not a scientific sample of these programs, so we cannot draw general conclusions that apply to all types of new learning ventures. But the results are like what pollsters find in focus groups. They provide general themes and other information that offer insights into an emerging sector of new K-12 learning environments.

The Fund surveyed leaders of 801 new learning ventures outside the traditional K-12 public and private school systems that received $7.5 million in VELA support since 2019. It received 413 responses from these leaders who founded new learning models that include microschools, virtual schools, pods, homeschool coops and programs, hybrid homeschools, and private schools. More than half (54%) are microschools or homeschool coops.

Here is what we are learning about these community enterprises.

The ventures

These ventures are young in their organizational lifecycle. At the time of their first VELA grant, more than 7 in 10 (72%) were three or less years old, with 3 in 10 (30%) less than one year old.

A majority (56%) are nonprofits, almost 3 in 10 (28%) for-profits, and the rest intend to incorporate as nonprofits. Nearly all of them (95%) have plans to grow.

Only 10% own their own space, with the rest renting space from faith organizations, corporate or individual private space, and public space like libraries or schools.

Their families

These ventures are not only for affluent families. Many have a core focus serving low income or historically underserved families. Almost 4 in 10 (38%) do this, while over 9 in 10 (93%) serve some portion of these groups.

Their finances

These ventures receive minimal external funding, with over 7 in 10 (73%) receiving 2022 external support only from their VELA grant and only 1 in 10 (10%) accessing public dollars. Over 8 in 10 (84%) charge tuition and fees or sell products and services, with 7 in 10 (70%) using tuition and fees as primary revenue sources.

Families receive discounts, scholarships, and reduced or free services. Some organizations have subscription fees or membership dues. They also use sliding income scales to determine a family contribution and are willing to exchange goods or services rather than receive an actual dollar payment.

So, grassroots K-12 civic entrepreneurs are creating a new sector of unconventional learning opportunities for families and young people. Permissionless innovation is the best way to describe their approach.

To summarize:

The permissionless innovation of grassroots civic entrepreneurs at the heart of this dynamism is creating new K-12 sector of community learning options to help young people flourish as adults. K-12 stakeholders and other community leaders should support these ventures and the families that use them.

At KaiPod Learning Centers, eight to 10 online learners or homeschoolers come together in person to work on their coursework and collaborate with their peers, supported by a highly-qualified KaiPod coach. Parents choose the curriculum that works best for their child delivered in a two-, three- or five-day plan.

Editor’s note: This analysis from Mike McShane, director of national research at EdChoice, appeared last week on forbes.com.

Earlier today, the National Microschooling Center released a new report on microschooling in America based on a survey of 100 current and 100 potential microschool leaders. It paints a fascinating portrait of an emerging sector of the education system at a critical juncture in its history.

By all accounts, microschooling is growing in America. Networks like Prenda, KaiPod, Acton Academies, and Wildflower are expanding across the country. Estimating the total number of microschooling families is challenging, but in several of our recent EdChoice polls one in 10 parents have responded that their children are enrolled in a microschool.

There are many reasons to believe that number is inflated, but even if the true figure is a quarter of that, we are still talking about millions of schoolchildren.

The study offered numerous interesting findings.

First, while more than half of microschools are located in commercial business spaces or houses of worship, almost 14% are located in a private home and 1% are located in an employer-owned facility.

This diversification of school location both shows the potential for microschools conveniently located close to where people live and work and also raises questions about how issues of zoning, building codes, and the like will intersect with microschooling.

Second, microschools are experimenting with the school day and week. While 54% of microschools are in class full time, 46% offer some kind of hybrid or part-time schedule. Our polling at EdChoice indicates that a substantial proportion of parents (routinely 40-plus percent) would like some kind of hybrid schedule, and the numbers of microschools offering such a school week lines up quite closely to those figures.

Third, to comply with local regulations, around a third of microschools operate as private schools, while just over 44% operate as “learning centers” catering to homeschooled students. It is an underappreciated fact that states actually regulate private schools to a substantial degree, and it appears that many microschools are not able to function within those strictures.

By operating as a learning or enrichment center for students who are classified by the state as homeschooled, schools are able to operate in the ways that they want to. It is not clear if this is the optimal path going forward.

To continue reading, click here.

Awakening Spirits, a private microschool that serves children with sensory issues, was launched by a former educator who taught English at a charter school for low-income students in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. The founder worked with Microschoolbuilders.com, a company that helps teachers and parents with the business side of education.

“I’ll show these people what you don’t want them to see. I’m going to show them a world without you. A world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries. A world where anything is possible.” – Thomas Anderson, “The Matrix”

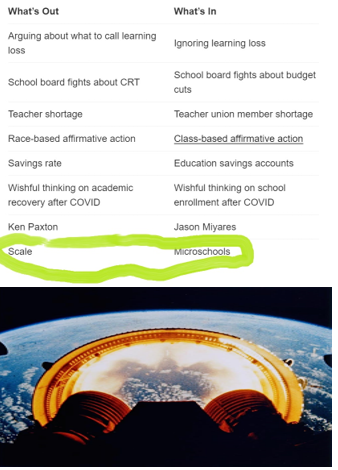

Andy Rotherham recently published his annual Eduwonk In and Out List, which he describes as unscientific, impressionistic, and often informed by “don’t tell anyone I sent this email” missives from colleagues. Here’s a partial look. (You can see the whole list here.)

While I’m obviously happy to see education savings accounts on the “in” list, the “Scale/Out and Microschools In” observation that caught my attention. Could it be that the “Scale” era of the choice movement is like a rocket booster that won’t be making the remainder of the journey forward?

The goal of bringing schools to “scale” always contained a difficult assumption: that we knew which types to attempt to scale up. That assumption contains within itself an implicit assumption of benevolent guidance.

Some guidance was explicit, such as the preference for “portfolio” choice models. In other instances, the urge for control was more subtle, for example, in heavy-handed charter school authorization.

For decades choice philanthropists heavily emphasized subsidizing certain types of charter schools during the “scale” era. In retrospect the overemphasis of a certain type of school in urban communities proved to be a strategy with a low educational and political ceiling. A power-struggle over K-12 policy broke out within the Democratic Party. Alas it did not end well.

The humble model of choice supporter viewed things differently than the scale school. The humility school started the assumption that we cannot know what is best for everyone. Values and preferences vary widely and genuinely. The scale school choice supporters want to control the choice space in order to make it “acceptable.” The humble looked for revealed demand in schooling, valuing the wisdom of crowds more than the preferences of the self-appointed.

Now let’s fast-forward to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our response to the COVID-19 pandemic will be studied for decades to come as a case study in fiasco. A great many American families, quite understandably, came to the conclusion that they wanted to increase their independence from a public education system that had crashed in such a spectacular fashion.

A Do-It-Yourself education movement, of which microschools are a part, had been quietly growing for decades. DIY rose up to meet the challenge of the COVID system failure. The genie shows no sign of going back into the bottle.

This does not mean that the “scale” institutions will disappear any time soon. As I related in a previous post, a disappointingly long seven decades passed between the first drilled well producing “rock oil” and the killing of whales for oil. School districts will last a good while longer.

Nevertheless, a powerful and complex set of factors has led to Rotherham’s In/Out list listing scale as “out” and micro-schools as “in.” Bespoke education is just getting warmed up, and it has a lot of room to run.

Let’s see what happens next, but color me optimistic.

Editor’s note: This article by Kerry McDonald, senior education fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education, appeared Sunday on the foundation’s website.

Editor’s note: This article by Kerry McDonald, senior education fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education, appeared Sunday on the foundation’s website.

When Michael Parsons envisioned his Montessori-inspired microschool in Charleston, West Virginia, earlier this year, he knew that he wanted to create an intentionally small learning environment where each child’s individual strengths could be nurtured and needs could be met.

He also valued a mixed-age classroom model, similar to a one-room schoolhouse, where young people could be in community together while working on academic content tailored to their learning level. Ample time hiking outside and walking to various local sites, such as the public library, were also key priorities.

Parsons pieced all of that together when he opened Vandalia Community School this fall in a cozy rented church space adjacent to a trail system near Charleston’s vibrant community resources. Parsons, who most recently taught at a community college, gravitated to the microschooling model which has been gaining popularity across the country and has been recognized by the West Virginia legislature as a specific educational approach.

“I love the microschooling model because it allows us to have a stable school community that provides our students with structured and predictable routines while also being flexible enough to meet the needs of each individual student,” said Parsons. “I think that microschooling presents a unique opportunity in a state as geographically isolated as West Virginia. It’s a structure that allows individual communities to envision and implement diverse educational models without exorbitant funding requirements or the need for high enrollment.”

Vandalia currently serves 10 students with two teachers. Parsons says he will likely cap enrollment at about 20 students to retain the small, personalized learning setting that he believes sets microschools apart from more traditional schools. He expects to open additional small schools as parent interest grows.

Like other microschools, Vandalia’s tuition is a fraction of the cost of traditional private schools. With West Virginia’s new education savings account program, Hope Scholarship, distributing $4,300 in state-allocated funding to almost every West Virginia K-12 student beginning next month, programs such as Vandalia become even more accessible to more families.

(Children who are homeschooled or already enrolled in a private school are currently not eligible for the Hope Scholarship.) When the Hope Scholarship program was delayed in the court system over the summer, Parsons announced that he would provide private scholarships up to $4,300 to the families in his microschool who were relying on that Hope Scholarship amount.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: William Mattox, director of the Marshall Center for Educational Options at the James Madison Institute and author of a new study related to this topic, provided this commentary exclusively for reimaginED.

Editor’s note: William Mattox, director of the Marshall Center for Educational Options at the James Madison Institute and author of a new study related to this topic, provided this commentary exclusively for reimaginED.

Any Florida education leader sitting down to watch tonight’s college football championship game may be tempted to bask in the glory of his or her own accomplishments. After all, Florida has become to K-12 education what the Alabama Crimson Tide has long been to college football – the standard by which everyone else measures themselves.

Florida recently received the nation’s No. 1 ranking in parental involvement in K-12 education according to the Parent Power Index, a state-by-state compilation from the Center for Education Reform. The title follows the Sunshine State’s recognition as No. 1 in K-12 education freedom by The Heritage Foundation.

And it adds to Florida’s recent year top rankings in state-by-state comparisons made by the American Legislative Exchange Council, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, and others. Yet, all this success begs an important question: Could the accolades Florida keeps receiving prove to be what Alabama football coach Nick Saban likes to call “rat poison”?

Saban has memorably invoked this term whenever football analysts have lavished mid-season acclaim on his team. He fears that fawning praise will go to players’ heads and diminish their drive for sustained excellence. Saban’s 2022 team did nothing to ease his fears.

Alabama’s 2022 team received all sorts of glowing headlines early in the season when pollsters crowned them the prohibitive favorite to win it all. But as the season wore on, the Crimson Tide failed to make consistent improvements. Ultimately, the team finished out of the college playoffs and in a ho-hum bowl game against a three-loss Kansas State team.

Bah. Humbug.

How can Florida’s education leaders learn from the Crimson Tide’s 2022 cautionary tale and continue their drive for sustained excellence?

Three words: Keep making improvements.

First, Florida needs to keep making improvements in providing scholarship opportunities for K-12 students. More than two decades after Florida’s first school choice programs were created, some Florida students remain ineligible for scholarship assistance – even though their parents pay taxes and the state will fund their education if they attend a public school.

The Florida Legislature ought to fix that in 2023. School choice scholarships should be available to all students. Yes, every kid.

Second, Florida needs to keep making improvements by encouraging K-12 innovation. Specifically, Florida needs to greatly expand its flexible scholarship programs so that families can take advantage of all sorts of emerging educational options including microschools, learning pods, virtual learning programs and hybrid homeschools.

Thanks to the Naples-based Optima Foundation, Florida is home to the first-ever classical school using immersive technology. Wearing virtual reality headsets, students travel back in time to witness re-creations of famous historical events and debates. (You can read a reimaginED feature on the school here.)

Openness to creative innovation like this ought to be the rule rather than the exception in K-12 education. Expanding flexible scholarships, known as education savings accounts, can help Florida continue to immerse itself in educational progress.

Finally, Florida needs to keep making improvements in the way that it helps students from disadvantaged communities. Specifically, policymakers need to give attention to addressing what Harvard scholar Raj Chetty calls the dearth of “positive neighborhood effects” in many lower-income communities.

One way to do this would be for Florida to work with the federal government to transform the Title I program into a weighted scholarship that funds students, not systems. This would give strong families an incentive to remain in and help revitalize disadvantaged neighborhoods rather than fleeing to higher-performing school districts, as has been the historic pattern.

If Florida can keep making improvements, the state can continue to be a leader in K-12 education. It can continue to sustain the excellence it has demonstrated in recent years. And it can continue to offer the hope of a better future to more and more Florida students.

As tonight’s kickoff approaches, let’s hope Florida education leaders learn a lesson from the 2022 Crimson Tide. Let’s hope they heed Nick Saban’s warning about “rat poison.”

Editor’s note: In anticipation of National School Choice Week, celebrated this year from Jan. 22-28, Andrew R. Campanella, president and CEO of the National School Choice Awareness Foundation, wrote this commentary for the corryjournal.com.

Editor’s note: In anticipation of National School Choice Week, celebrated this year from Jan. 22-28, Andrew R. Campanella, president and CEO of the National School Choice Awareness Foundation, wrote this commentary for the corryjournal.com.

For parents across the country who have been enlightened or frustrated by education during the COVID-19 pandemic, a new and exciting innovation is emerging, creating new opportunities for families.

It's a 21st century way of approaching learning, with flexible options popping up in local communities across the country. Though each is unique, these new options broadly fall under the category of microschooling and learning pods.

Perhaps someone you knew joined a pod in the absence of in-person schooling during the height of the pandemic. Maybe your sister-in-law has been raving about the public charter microschool she found for her son. By challenging the conventional wisdom of how schooling must be done, microschooling and learning pods refocus the education conversation around everyone's shared goal: the educational success and happiness of students.

If you want to find out more about these new learning options, or the traditional public, public charter, public magnet, private, online, or at home education options available to your family, you're in luck this month.

National School Choice Week will take place January 22-28, 2023, organized by the National School Choice Awareness Foundation to shine a positive spotlight on effective education options for children.

As a parent in 2023, you're bound to have questions about the K-12 system, which has changed rapidly in our lifetimes. If you're not familiar with all your school choices, or what to ask when comparing them, you're not the only one.

Today, more than ever, families are interested in school choice, and states are creating policies that increase the opportunities for families to choose a school. For the majority of parents in this country, the real question isn't whether you have school choice, but how you'll use it.

To continue reading, click here.

Bloom Academy in Las Vegas, Nevada, available to children ages 5 to 14 from all socioeconomic backgrounds, benefited from the resources and guidance provided by National Microschooling Center to fine-tune its self-directed learning approach. The academy’s philosophy is based on the idea that children are natural learners who should have unlimited opportunities to play, make mistakes, and develop their interests.

Editor's note: In keeping with our year-end tradition, the team at reimaginED reviewed our work over the past 12 months to find stories and commentaries that represent our best content of 2022. This post from newsfeature writer Tom Jackson is the seventh in our series.

It’s well documented that millions of parents turned to microschools as a result of campus shutdowns during the long Covid-19 nightmare. These nimble learning centers provided safe gathering spaces and tailored learning experiences for cast-adrift students and comported with parents’ work demands.

It’s well documented that millions of parents turned to microschools as a result of campus shutdowns during the long Covid-19 nightmare. These nimble learning centers provided safe gathering spaces and tailored learning experiences for cast-adrift students and comported with parents’ work demands.

More than two years later, what had at first seemed a temporary salve born of desperation looks more like a godsend to a long-festering problem. Writing for the Manhattan Institute, researcher Michael McShane lays out the framework and the appeal of microschools:

Neither homeschooling nor traditional schooling, [microschools] exist in a hard-to-classify space between formal and informal learning environments. They rose in popularity during the pandemic as families sought alternative educational options that could meet social-distancing recommendations.

But what they offer in terms of personalization, community building, schedules, calendars, and the delivery of instruction will have appeal long after Covid recedes.

Long-time education choice advocate Don Soifer concurs.

“For whatever reason, families are just rethinking the public education system,” he says. “The research is telling us now that microschooling serves 2-1/2 to 3-1/2 million learners as their primary form of education.”

That puts microschoolers at about 2% of the national student population, a number higher than K-12 Catholic school enrollees, according to the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

“It really wouldn’t surprise us at all to see microschools capture 10 percent of market share,” Soifer says.

In short, microschooling is no flash-in-the-pandemic phenomenon. In response and anticipation – and backed by Stand Together Trust – Soifer launched just last week the National Microschooling Center, a Las Vegas, Nev.-based resource hub designed to provide a smorgasbord of resources and technical assistance in support of the growing wave of tiny learning environments across America.

Soifer’s credentials for the task are as impeccable as his interest is diverse. Active in President George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind initiative, he served on charter school boards in Washington, D.C., and Nevada, and has been president of Nevada Action for School Options since September 2017.

At the start of the pandemic, Soifer and his team partnered with the city of North Las Vegas to create the Southern Nevada Urban Micro Academy, which opened in August 2020. It’s not often the local media uniformly praise anything, Soifer noted, but with academic scores surging amid students, parents, educators, and lawmakers who found themselves uniformly delighted, SNUMA managed to harmonize even the typically rancorous media choir.

Notable, says National Microschooling Center chief innovation officer Ashley Campbell, is how quickly the students adapted, then thrived.

“It was so exciting to watch the transformation of the children as they … [had] the chance to own their own education, follow their own learning trajectory, set their own goals, and live up to those goals,” Campbell said.

“It was amazing to watch a group of fifth- and sixth-grade students shift from a place where learning wasn't cool, it wasn't cool to be smart, to a place where they were encouraging each other to meet their goals and exceed them.”

The year’s contagion wasn’t confined to Covid-19, it turns out.

“Movement-building is a gradual process, and frankly one that the school choice movement has had mixed success over time in doing,” Soifer says. “And even that success is different in particular jurisdictions. But as people have become familiar with this different way of learning — in ways that public schools don’t encourage — it gets to be popular. And that makes for concerted, dedicated, sustained movement-building.”

The prevailing menu of microschools comes in three forms: independent (standalone pods or centers), partnership (with a public, private, or sectarian entity), and corporate (such as KaiPod Learning or Prenda). National Microschooling Center is designed to increase the momentum for all of them in four key ways: by cultivating and growing demand; by building and strengthening microschool leader capacity; by driving growth-friendly policies; and by mobilizing united communities of practice.

“It’s really important to note that we’re not talking about taking a model that works here and placing it somewhere else,” Soifer says. “If you’re a microschool that wants support and resources, we’re not going to require you to follow a design. It’s about building a program to meet the needs of your particular learners, equipping your leaders for success, and making sure they know how to build relationships with families.”

In other words, he says, it’s not about the center saying, “Here’s the model and let’s stick to it.”

Prioritizing bespoke learning conditions is how Soifer’s group has acted at the local level, says Sarah Tavernetti, principal of Bloom Academy in Las Vegas.

“We don't do testing. Or grading,” she says. “What else? There’s no homework, we don't implement a curriculum, so we're fully self-directed.”

Rather than telling students what they’re going to learn about, Bloom Academy encourages them to let their curiosities and natural inclinations guide their day.

“We’re here to support them, bring in people from the community who are knowledgeable about the things that they're interested in,” Tavernetti adds.

Some students attend Bloom Academy full time, some part time, some as part of their homeschool program.

“We’re kind of this umbrella for all those different philosophies,” Tavernetti says.

And Team Soifer is perfectly okay with that.

“Don and Ashley started out as advisors,” Tavernetti says. “Now we think of them as friends.”

Plainly, then, what the National Microschooling Center won’t do is require schools to purchase particular curricula or licenses or get locked into a contract. Instead, the center offers resources and guidance, plus the opportunity for connectedness — mobilizing united communities of practice.

Education, in every form, often leaves practitioners with the sense that “they’re out on an island doing their own thing,” Campbell says. “Teachers spend their day in the classroom with the kids, and they rarely have a chance to talk to other adults.

“We’re making sure that our microschool leaders are not feeling isolated, that they’re able to come together, brainstorm with each other, and solve problems together.”

But the bigger picture is never far from Soifer’s mind. Topping the National Microschooling Center’s action plan is energizing and organizing a coast-to-coast school-choice advocacy movement. There’s already good news on that front, especially in Arizona, but also in Florida, Indiana, and West Virginia.

But even in less choice-friendly Georgia, microschools are thriving in and around Atlanta. It’s all about understanding the lay of the land, Soifer says, and working the topography to your best advantage.

“There’s energy here like we haven’t seen,” he says. “And [microschools] don’t compete with each other; they really want to see each other succeed and thrive.”

If that’s truly the case, National Microschooling Center has arrived on the scene at precisely the right moment.

Ryan Graves, a 12-year-old “Primer kid” first homeschooled as a fifth-grader, asked his teachers if he could use Primer Rooms to create his own coding class. Now he’s teaching other students how to code and build their own websites.

Editor's note: In keeping with our year-end tradition, the team at reimaginED reviewed our work over the past 12 months to find stories and commentaries that represent our best content of 2022. This post from senior writer Lisa Buie is the second in our series.

Imagine a school that offers lessons from the nation’s top subject matter experts online, lets students learn social skills from compassionate, in-person teachers in a brick-and-mortar classroom, and encourages them to pursue their passions with peers from all over who share similar interests in a virtual club setting.

Imagine a school that offers lessons from the nation’s top subject matter experts online, lets students learn social skills from compassionate, in-person teachers in a brick-and-mortar classroom, and encourages them to pursue their passions with peers from all over who share similar interests in a virtual club setting.

Welcome to Primer Microschools, a hybrid that merges on-site and virtual school in a way that its founders say engages students more than either method can do alone.

The unique format emerged from the partnership of 15-year educator Ian Bravo and Silicon Valley entrepreneur Ryan Delk.

Though they came from diverse backgrounds, they have one thing in common: each thinks education should provide more for kids, especially their own.

“I went to a public school,” said Bravo, a former Teach for America corps member who went on to become a teacher and administrator for the KIPP network of charter schools before deciding to strike out on his own. “That’s all I’ve ever known.”

Ian Bravo

Bravo said traditional school didn’t spark his interest in pursuing a career in education. Instead, an enrichment program that he and his twin sister qualified for through testing was the catalyst that turned him onto learning, putting him on a path of advanced courses in middle school and an International Baccalaureate program in high school.

“It was a smaller setting one day a week,” he recalled. “It was very project based. Even if it was only 20 percent of my hours spent, 90 percent of my memories are from that program.”

Another pivotal moment came when a high school history teacher encouraged him to cut math class. Yes, you heard right.

“He was a bit of rebel and would always play devil’s advocate and get the class fired up about world history,” Bravo said. “He called me up to his desk and said, ‘Hey Ian. Don’t go to that stupid math class. Go hide in the book closet and read your history.’

“I took that as a cue and chose strategically what classes I would take. It taught me that you have to take your education into your own hands, and so that was a very eye-opening experience.”

Those experiences stayed with Bravo through college and into his teaching career. At a traditional school in the Bronx and later at KIPP, he worked to add innovative ways of learning.

They really hit home when he and his wife, also a KIPP teacher, had their own children. When his first daughter was born, Bravo said, he wanted to find a learning environment that reflected what he wanted her education to look like.

“I realized I didn’t see it anywhere,” said Bravo, who helped start and lead the first KIPP middle school in the Miami area.

Then in 2020, the pandemic hit. The couple had had their second daughter, and Bravo stepped away from leadership to start his own form of schooling.

“I wanted to start something to allow the girls to deeply explore their interests and not be restricted in a one-size-fits-all classroom,” he said.

Ryan Delk

Delk grew up in Florida and was all set to start kindergarten, when at the last minute, his mom, a former public school teacher, decided she could do a better job with her bright and creative child.

So, she homeschooled him until eighth grade.

For Delk, that meant learning about the American Revolution by visiting historic sites in states that formerly were America’s 13 original colonies. It also meant learning about the digestive system by crawling through cardboard tubes stretched throughout the house.

“My parents’ main goal was for me to love learning,” he said.

After graduating from a traditional high school, Delk went to the University of Florida with plans to study banking and eventually start a career on Wall Street. He soon learned that wasn’t his passion.

What did interest him was creating value and making it available to others. He started a business fixing friends’ iPhones. He also worked for Square, a startup at the time, by selling it to businesses near the university.

A stint in Kenya to help a friend create tech incubator space and tech-related conferences showed him that rather than returning to college, his future was elsewhere. He moved to Silicon Valley, where he worked for tech companies and invested in startups.

In November 2019, Delk, who by then had become a father, teamed up with a partner to develop Primer, a company that connected kids to each other, allowing them to share hobbies and interests.

The timing couldn’t have been better. The coronavirus pandemic shuttered school campuses a few months later and homeschooling rates exploded.

Delk promoted Primer to the nation’s 2.4 million homeschool families as a supplement to curriculum. But his ultimate goal was to create something that would fundamentally fix a broken traditional educational system.

Bravo, who had the same dream, connected with Delk through a lead engineer at Primer.

After a successful pilot last summer, Primer Microschools is set to launch at six locations in Miami in August for students in grades 3 through 6. Tuition varies based on eligibility for financial aid. State K-12 scholarships, administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog, also are an option for families.

The team’s goal is to expand to other areas of Florida, and eventually, to other states.

A typical day at Primer Microschools starts with a half hour of team building, mindfulness activities such as yoga, and goal setting led by an in-person teacher. Math lessons follow with an online instructor and off-line work, followed by recess at 10 a.m. English lessons are scheduled for 11.

From noon to 1 p.m., students pursue “passion projects,” which are limited only by their imagination and creativity. Examples range from writing songs and putting on a concert to researching rising sea levels.

After an hourlong lunch, students study science and social studies before coming back together to end the day. They have access during any free time to Primer’s virtual clubs, such as the Storytellers Club and the Artists Club.

Lessons are led by teachers as opposed to guides, and with student-teacher ratios of 15:1, there’s plenty of opportunity for individual attention. Primer provides each student with a laptop to access lessons and do homework, bridging any technology gaps.

Response from instructors has been robust.

“We put up an ad on Indeed.com at 1 a.m.,” Bravo said. “By 6 a.m., we already had 50 applications.”

Applicant families for the schools’ 100 spaces are being selected based on interviews and student-created projects. Test scores and grades are not considered.

“We want students who are creative and who are curious,” Bravo said. “We want students who will flourish.”