Milton Friedman and his free-market ideas may have been anathema to the political left, but he was right about one thing: School choice.

Daniel Grego, the director of Milwaukee's TransCenter for Youth and an acolyte of the likes of Ivan Illich and Wendell Berry, made that case in the journal Encounter. His argument, outlined in a 2011 article we stumbled upon recently, is worth highlighting, in part, because it reinforces a theme we've explored on this blog for quite some time: The left-of-center appeal of educational choice.

"It is time for people on the left to overcome 'the nonthought of received ideas' and admit that giving poor families resources is a progressive public policy," Grego wrote.

The writer helped lead an ill-fated effort, backed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, to bring more "small schools" to his city. An article in Milwaukee Magazine said he was intent on ending "the longtime war" between public-school supporters and advocates of the city's pioneering school voucher program.

And while he wound up sharing Friedman's conclusions about the benefits of educational choice, he followed a different intellectual path to arrive at that position. (more…)

The apparent simplicity of Milton Friedman’s free market model of parental choice is truly appealing. Let the parent decide. Here’s the money. Go choose. This is efficient liberty in its purest form – and so simple.

Or is it?

Is subsidized parental choice analogous to my easy liberty to choose Butter Brickel at Safeway, or a Honda at the car dealer? I fear not. It is, rather, the decisions, not even of the intended consumer, but of an adult authority who imposes a thirteen-year, profoundly formative experience upon another human being, who happens to be his or her own child.

The parent issues the command; the child obeys, as does the school, which is bound by contract to harbor the child and to deliver the chosen brand of education. The arrangement is, thus, a choice of the parent and a form of obedience by the child. This, I suggest, is an odd example of free enterprise; it more resembles the choice of diet for the prisoners by the warden.

Does this observation imply that the market conception of parental choice is irrelevant to the debate? Of course not.

This is the all-in-one version of our recent serial about efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot. It's part of our ongoing series on the center-left roots of choice.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation.

***

Cue “Staying Alive.”

Disco was king. Jimmy Carter was president. And across the bay from Berkeley, the punk band Dead Kennedys was blasting its first angry chords. But in 1978, Coons and Sugarman still hadn’t gotten the carbon-copy memo that the ‘60s were over.

The ballot initiative they detailed in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice,” wasn’t gradual change, organic growth, nibbling at the edges.

It was revolution. (more…)

This is the latest in our series on the center-left roots of school choice, and the last part of a serial about a proposed voucher initiative in late ‘70s California. In Part III, libertarian choice supporters reject a ballot proposal pitched by Berkeley law professors, and offer their own.

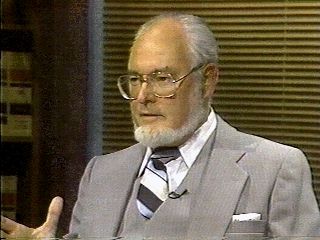

The professors wanted Milton Friedman’s blessing. So did the libertarians.

Calling Friedman was the “first and natural thing to do,” Berkeley law Professor Jack Coons recalled in an interview. The two had known each other since the early 1960s, when both lived in Chicago. Coons hosted a radio show; Friedman was a frequent guest.

As luck would have it, Friedman was now based at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, in nearby Palo Alto. He and Coons and their wives occasionally met for dinner.

Initially, Friedman was excited and encouraging about the ballot initiative, Coons said. Then he wasn’t.

The regulations spooked him, Coons said. Friedman never told him directly. But he heard as much from potential donors to the initiative campaign, and it wouldn’t have been surprising. Friedman’s biggest fear about school choice was government intrusion.

According to Coons, donors told him Friedman had been in contact with them and said the plan was wrong-headed. He convinced them to hold off on contributions, and to wait for better school choice proposals down the road.

***

The libertarians had better luck.

Activist Jack Hickey said he sent Friedman a copy of his "performance voucher" proposal, and talked to him by phone. He said Friedman liked it enough to give it a positive review in writing. As proof, he produced a letter from Friedman on Hoover Institution letter head.

Friedman wrote that he liked how the performance voucher would curb government’s role in education, but was bothered by heavy reliance on standardized testing. He concluded, though, that “any one of the three approaches (an unrestricted voucher, your approach, or an appropriately designed tax credit) would be vastly superior to our present system.”

Both David Friedman, Milton Friedman’s son, and Robert Enlow, president of the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, said the letter appears to be authentic.

***

For some, two competing choice proposals weren’t enough. In the summer of 1979, petitions began circulating for a third. (more…)

This is the latest installment in our series on the center-left roots of school choice, and Part III of a serial about school choice efforts in late ‘70s California. Part II included a closer look at U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan and the game-changing voucher plan he wants to push, while school boards and teachers unions came out swinging.

South of San Francisco, an electronics engineer and inventor in Redwood City read about the liberal-led California Initiative for Family Choice and thought: Disaster.

Not because it would kill the public school system. Because it would perpetuate it.

Jack Hickey saw too many regs, too little freedom, too much potential to “contaminate” private schools. He was certain the massive school choice plan engineered by Berkeley professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman would curtail choice, not expand it.

“I looked at that and said, ‘That’s bad, that’s really bad,’ “ Hickey said in an interview.

Hickey wasn’t content to grump. The libertarian activist would eventually run for office 18 times, including for governor, U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives. In this case, he nimbly sketched out a counter-proposal, something he called a “performance voucher.”

Then he and Roger Canfield, a police consultant in nearby San Mateo, began their own sprint to the ballot.

***

At the time of his meeting with Congressman Leo Ryan, Jack Coons was best known as one of the attorneys who changed how public schools are funded in California.

He and Stephen Sugarman were key players in a legal effort that began in 1968 with a widely publicized case, Serrano v. Priest. It charged that the way California financed public schools – by relying heavily on local property taxes, resulting in huge disparities between rich and poor districts – violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Over the course of a decade, Serrano led to three California Supreme Court rulings that spurred the state legislature to mitigate funding disparities between districts. It’s also credited with sparking school finance reform in other states, even though a ruling from a similar case in Texas was struck down in a 5-4 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Coons’s embrace of school choice flowed, initially, from the funding inequities he saw. Ultimately, he and Sugarman, his protégé and intellectual partner, came to this conclusion: Giving poor parents more power to choose schools for their children best allowed them to rise above an entrenched education system blatantly rigged against them.

The professors first fleshed out their voucher idea in 1971, in a 118-page treatise for the California Law Journal. In the foreword, another Berkeley professor channeled a view about public schools that wasn’t uncommon for progressive thinkers of the era:

If a set of families enters a state park to go hiking, that group would be shocked indeed to discover that the scenic trails were reserved for its richer members and that only barren and rocky paths were held open for the poor. Nevertheless, our public schools operate in such a discriminatory way.

Not all choice enthusiasts looked primarily through that lens.

***

Like Coons and Sugarman, the libertarians wanted to end the old regime, not modify it.

Libertarian Jack Hickey didn't like the Coons-Sugarman school choice proposal, and crafted a competing proposal for "performance vouchers."

Jack Hickey and Roger Canfield’s proposal would abolish government-run schools, end compulsory education and stop measuring academic progress merely by number of instructional days (wonks call that “seat time.”) Every parent would be given a voucher of equal value, $2,000 per year. (Per-pupil spending in California at the time was about $3,000 per year.) Through a contract with the state, the parents could spend the money on a school, on a teacher or teachers, on educational materials, or on any number of other things and combinations.

The performance voucher had, in the words of Hickey and Canfield, “divisibility.” In that respect, they, like Coons and Sugarman, foreshadowed today’s latest spin on vouchers – education savings accounts – years before think tanks fleshed them out.

But the performance voucher also had another irregular feature that made it distinct: It couldn’t be redeemed until the student showed progress, as determined by a standardized test.

No progress. No payment. (more…)

This is the latest installment in our series on the center-left roots of school choice, and Part I of a series within a series about school choice efforts in late ‘70s California.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation. (more…)

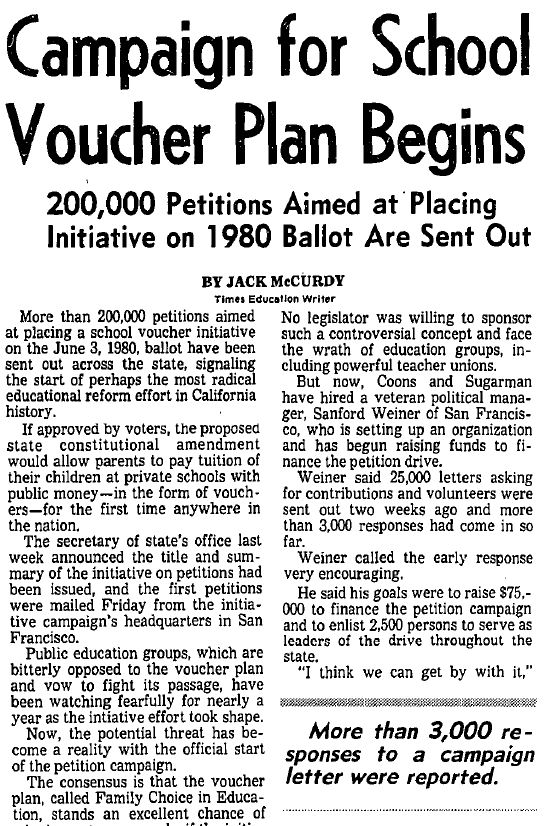

In disco-era California, Berkeley professors were the insurgents behind a school choice plan so big and brazen, it rattled the state’s education establishment for a year.

The effort led by Berkeley professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman to put school choice on the 1980 ballot in California drew widespread publicity, including stories like this one in the Los Angeles Times.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman championed choice as a means of liberating low-income families. They viewed the public school system as demeaning and elitist, and in 1978, they unexpectedly found an influential ally: U.S. Congressman Leo Ryan.

In as much time as it took for “Le Freak” to rocket up the Billboard charts, their voucher vision went from academic template, to proposal for a statewide ballot initiative, to dead-serious pitch that compelled everyone from Al Shanker to Milton Friedman to pay attention.

On the educational Richter scale, this was, potentially, The Big One.

The California story would be worth telling for those nuggets alone. But it’s also a head-spinning footnote in a better-known story. How incredible that Coons and Friedman, titans and rivals in the school choice universe, would both be in the San Francisco Bay area in the late 1970s. How unbelievable that a planet-shaking story that metastasized in that same time and space would careen into the education realm. How surreal that maybe just maybe, it would change a movement’s trajectory.

Sixty years after Friedman crystallized the idea of private school  vouchers, school choice is easing into the mainstream. Forty-three

vouchers, school choice is easing into the mainstream. Forty-three

states now have charter schools. Another 25 have vouchers and/or tax credit scholarships and/or education savings accounts. But the total number of K-12 students served by those options is still a tiny fraction of the whole. Meanwhile, creation of new options continues to be dogged by common misperceptions that school choice is almost exclusively right-wing.

What if, 35 years ago, voters in the biggest state in America had said yes to a school choice plan that was far bigger than anything around today? What if the first state to adopt a statewide voucher plan had been California in 1980 rather than Florida in 1999? What if the revolutionaries had been Left Coast liberals and a Democratic congressman, rather than a Republican governor in the South?

Next week, for the latest in our Voucher Left series, we’ll kick off a series within a series. Please join us for a little California Dreamin’ …

Between the late 1970s and late 1980s, bad luck derailed three efforts to put a center-left vision for school vouchers on the statewide ballot in California.

This is the fourth post in our series on the Voucher Left.

The hope to secure school choice for lower-income parents has invoked many justifications beside free market theory. These broader conceptions of choice, however, have failed to secure serious consideration in political discourse about choice.

Devout marketeers often forego, or even oppose, reliance upon these would-be friendly pictures of the effects of choice. They are seen as obscuring, even corrupting, free-market dogma: let individual taste determine what is the good. Personal preference itself becomes the goal: the market is the end instead of the instrument. Those who would argue in the name of more particular outcomes are “voucher left.”

I will pursue this hurtful confusion about goals, but I will also recall that its mischief has been aggravated by sheer bad luck — surprises that have undermined and long delayed what was in the 1970’s a promising political career for choice for all families. I will describe some of these odd events and their part in the long frustration of that cause. Note that I am myself a veteran centrist (“left”?) in this cause and critics on either side are welcome to correct my description of the philosophical clashes. My personal recollections of bad luck, however, seem beyond such attack (except as whining, which of course they are).

Subsidized parental school choice, a concept from the 18th and 19th centuries, was revived in the 1950s as what seemed to Milton Friedman an obvious instance of economic libertarianism. A full school market with vouchers for all would be an extension of freedom for both provider and consumer, allowing the parent an instrument with which to define the good life. That freedom should be virtually plenary; this is simply good economics, hence public policy. To say more in its justification (test scores perhaps excepted) would stray from school choice’s image as itself determining the good. Do I exaggerate? Not much in respect of the hard-core “voucher right;” choice justifies itself. To say much more risks government defining its limits for you. So, at least, was the libertarian mood music that gained volume beginning in the ‘70s. Marketeers had yet to appreciate that full freedom for the school provider might not be the same liberating experience for the consumer.

Friedman and company added to the ideological confusion, seeming never to note that subsidized school choice is quite unlike other markets in respect to the value of freedom itself. Indeed, it could be deemed freedom’s opposite. For the assignment of the child to the school — if an act of freedom in any sense — is the “freedom” of the adult authority, whether parent or state. It is the freedom of one person holding office to tell another person what he will or will not do. Thus, would-be champions of “choice” are, more accurately, champions of a particular locus of power. We begin to see that, while there are many justifications for parental authority — and market talk helps to a point — this is not a pure case of liberty. The debate rather is about which of two masters will pick Mary’s teacher to act both in her “best interest” and that of society. And, all claims about who is the best decider must face up to both aspects of parental choice — freedom and power.

A second sort of bogeyman began gradually to make his appearance. (more…)

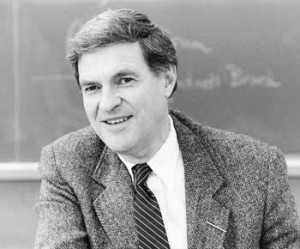

Ted Sizer: School vouchers "could cause a kind of decentralization which would promote diversity, pluralism, responsiveness to the needs of the community being served and, indeed, even greater efficiency."

This is the first post in our series on the Voucher Left.

It starts by condemning America for failing to provide equal opportunity in education. It ends with a knock on the war in Vietnam. Inbetween, it offers a template for a $15-billion-a-year national voucher plan that “will frankly discriminate in favor of poor children.”

Published in 1968, "A Proposal for a Poor Childrens Bill of Rights" is a historical gem – a seminal document of Voucher Left history that remains curiously buried. It was co-written by Theodore “Ted” Sizer. Then dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Sizer would become so influential and beloved an education reformer that 1,000 people would attend his funeral in 2009, including Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick.

Sizer’s Wikipedia entry doesn’t mention his embrace of school choice. Neither does his New York Times obit. But in the 1960s and ‘70s, he and other liberal academics like Christopher Jencks, Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman were all promoting vouchers. They didn’t dismiss the market power underscored by Milton Friedman. But they also favored regulations that, in their view, would ensure low-income families had real power over education bureaucrats and real access to new education environments. Wrote Sizer in his manifesto:

Ours is a simple proposal: to use education – vastly improved and powerful education – as the principal vehicle for upward mobility. While a complex of strategies must be designed to accomplish this, we wish here to stress one: a program to give money directly to poor children (through their parents) to assist in paying for their education. By doing so we might both create significant competition among schools serving the poor (and thus improve the schools) and meet in an equitable way the extra costs of teaching the children of the poor.

Sizer likened his idea to the higher-education planks of the G.I. Bill. It differed from “conservative” K-12 voucher proposals in key ways.

Though the details are fuzzy, Sizer wasn’t talking vouchers for all, or vouchers just for private schools. (He doesn’t use the term “voucher” either, instead describing his proposal as a “supplementary grant.”) For political expediency, he thought half the school-age population should be eligible. And he suggested a sliding-scale for the value of the voucher, so the poorer the family, the greater the amount. (Berkeley law professors Coons and Sugarman proposed something similar in the 1970s, and tried to get it on the ballot in California. It attracted gobs of publicity, but ultimately failed to secure enough signatures.)

Sizer pushed back against the idea that vouchers were conservative. He struck back at critics who said they would “destroy the public schools.” (more…)

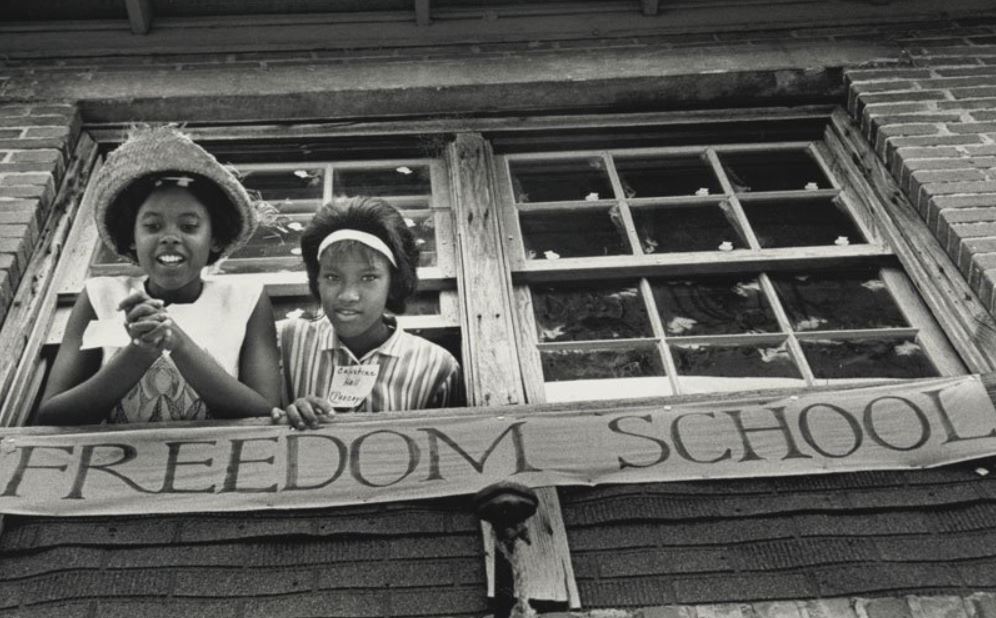

Despite what the story lines too often suggest, school choice in America has deep roots on the political left, in many camps spanning many decades. Mississippi Freedom Schools, pictured above (the image is from kpbs.org), are part of this broader, richer story, as historian James Forman Jr. and others have rightly noted. Next week, we’ll begin a series of occasional posts re-surfacing this overlooked history.

By critics, by media, and even by many supporters, it’s taken as fact: School choice is politically conservative.

It’s Milton Friedman and free markets, Republicans and privatization. Right wing historically. Right wing philosophically.

Critics repeat it relentlessly. Conservatives repeat it proudly. Reporters repeat it without question.

It has been repeated so long it threatens to replace the truth.

The roots of school choice in America run all along the political spectrum. And to borrow a term progressives might appreciate, the inconvenient truth is school choice has deep roots on the left. Throughout the African-American experience and the epic struggles for educational opportunity. In a bright constellation of liberal academics who pushed their vision of vouchers in the 1960s and ‘70s. In a feisty strain of educational freedom that leans libertarian and left in its distrust of public schools, and continues to thrive today.

This is not to deny the importance of the likes of Friedman in laying the intellectual foundation for the modern movement, or to ignore the leading role Republican lawmakers have played in helping school choice proliferate. But the full story of choice is more colorful and fascinating than the boilerplate lines that cycle through modern media. Black churches and Mississippi Freedom Schools are part of the picture. So is the Great Society and the Poor Children’s Bill of Rights. So is U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, D-N.Y., and Congressman Leo Ryan, D-Calif., the only member of the U.S. House of Representatives to be assassinated in office.

Perception matters. Perhaps now more than ever. There is no doubt far too many people who consider themselves left/liberal/progressive and identify politically as Democrats do not pause to consider school choice on its merits because they view it as right-wing and Republican (or maybe libertarian). In these polarized times, people have never identified with ideological and party labels so completely, and, I fear, so often made snap judgements based on perceived alignments.

School choice isn’t the only policy realm to suffer from false advertising, but in the case of vouchers, tax credit scholarships and related options, the myths and misperceptions appear particularly egregious. (Note: I work for Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog and administers Florida's tax credit scholarship program, the largest private school choice program in the nation.) The forgotten history means newcomers to the debate get a fractured glimpse of the principles that have long fueled the movement. And it means critics can more easily cast contemporary supporters on the left as phonies or sellouts, as opposed to what they really are: heirs to a long-standing, progressive tradition.

We at redefinED would like to redouble our efforts to change that. So, beginning today, we’re going to offer a series of occasional posts about the historical roots and present-day fruits of school choice that are decidedly not conservative.

We’re calling it “Voucher Left.”

We hope to offer entries big and small, some by redefinED regulars, some by guests. We may rescue a historical document from the dust bin. We may serve up a profile or podcast. Maybe we’ll reconstruct some fascinating but forgotten moments in the rich history of choice, like what happened in California in the late 1970s when a couple of Berkeley law professors tried to get a revolutionary voucher proposal on the statewide ballot. (Here’s a bit of tragic foreshadowing: But for Jim Jones of the People’s Temple, vouchers today might be considered a liberal conspiracy.)

There is no set schedule for the series. We’ll roll out posts as often as time permits, and as often as we can keep digging up good stuff. Look for the first two right after Labor Day.

In the meantime, a few caveats:

We didn’t coin the term “voucher left.” As far as we can tell, all credit goes to writer (and former fellow at the Center for American Progress) Matthew Miller. In a 1999 piece for The Atlantic, Miller used the term to describe the ‘60s era choice camp that included John E. Coons and Stephen Sugarman, Berkeley law professors who co-founded the American Center for School Choice, which helped put this blog on the map. We thought the term perfect – and just as fitting an umbrella for choice’s other progressive pillars. (more…)