O God of earth and altar,

O God of earth and altar,

Bow down and hear our cry,

Our earthly rulers falter,

Our people drift and die;

The walls of gold entomb us,

The swords of scorn divide,

Take not thy thunder from us,

But take away our pride.

-GK Chesterton, Space Age Systems Collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse is one of the great mysteries of history and archeology.

We know what happened: Multiple eastern Mediterranean civilizations – the Mycenean Greeks, the Hittites and others – disappeared within a 50-year span, roughly 1200 to 1150 BC. What we don’t know are the reasons why it happened. Written records from this period are scattered and not entirely reliable; one of the unfortunate byproducts of this collapse was a large reduction in literacy rates.

Get ready for some more of this. History doesn’t repeat, but it does echo.

One of the written records we do have is the inscription pictured above, left behind by Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses III (presumably the giant bow-wielder trampling the bodies of crushed enemies) who claimed to have smashed an invasion of the mysterious “Sea Peoples.”

PRIII likely exaggerated the scale of his combat prowess, but a number of other coastal civilizations did not live long enough carve propaganda into rock. Several simply vanished only to slowly emerge from dark ages centuries later. Egypt fared relatively well, surviving the Bronze Age collapse, but was never the same afterward.

Scholars have used the phrase “systems collapse” to describe what happened in the Late Bronze Age. You can get a flavor for the phenomenon in an article by Nicole Gelinas on New York City’s current economy, which describes how interdependent the city’s industries are and how none of them currently are running strong enough to support each other.

The eldest among us today have seen multiple examples of system collapse. European imperialism and the Soviet Union both dissolved during our lifetimes for instance. Other large systems, like Pax Americana and the European Union, obviously are under considerable strain.

American public education also is facing an unprecedented challenge. Like Bronze Age Egypt, American public education will survive. K-12 funding is guaranteed in state constitutions across the country, making it as permanent an institution as one can imagine in American life. But unlike Ramses III, we should not attempt to deceive ourselves regarding the scale of the damage being done not only by the pandemic but also to the response to it.

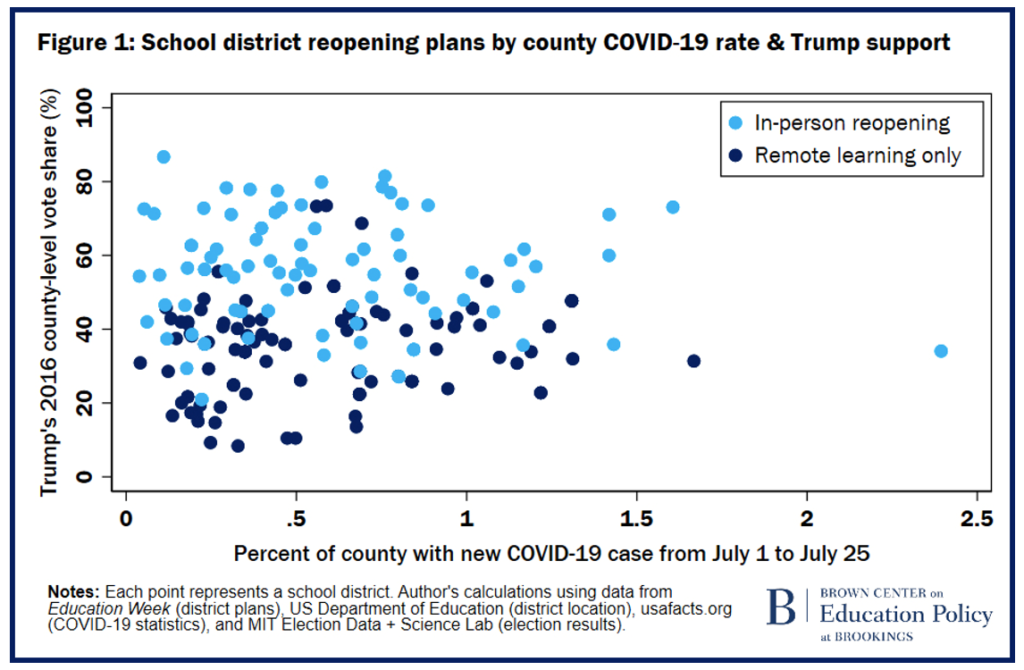

Earlier this year, the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution published the scatterplot above regarding school district re-openings. As you can see, the decision regarding remote versus in-person learning by district has little to do with COVID-19 infection rates, and a great deal to do with the political leanings of the county in which the school district operates.

Notice especially the cluster of dark blue dots on the bottom left of the chart, representing remote learning only districts in counties with low COVID-19 countywide infection rates.

Chad Alderman, senior associate partner at Bellweather Education Partners, recently examined 10 large school districts to see how much instruction time they were delivering to students by whatever means – in-person, remote, etc. Alderman wrote:

The term ‘chronic absenteeism’ is defined as missing 10% or more of school days in a year. By that standard, the majority of K-12 students might be considered chronically absent this school year.

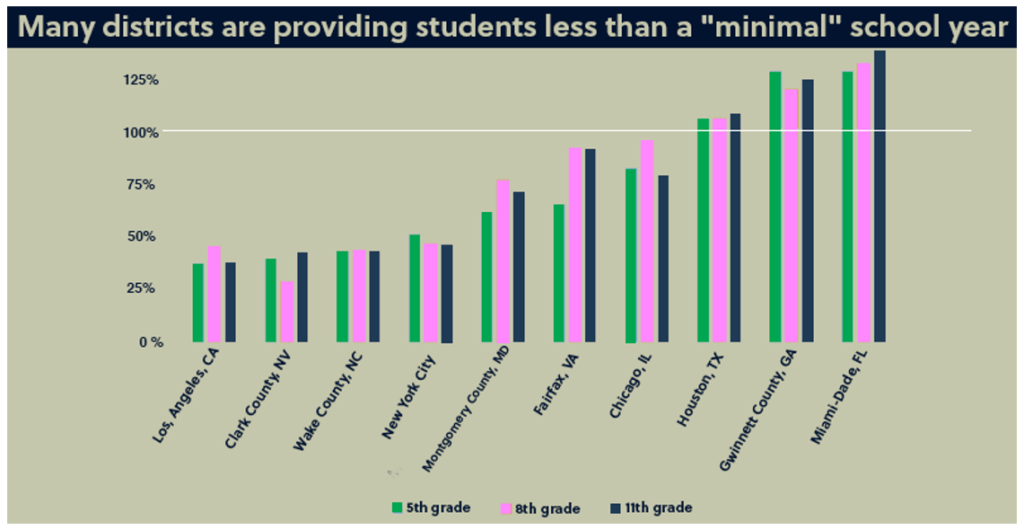

Alderman included the chart below that details instruction time by district. Congratulations to Miami Dade, Gwinnett County Georgia and Houston. Otherwise, read it and weep.

A few notes on the above disaster.

The Los Angeles Unified School District, the nation’s largest, had a world of academic problems before COVID-19. Cutting instruction by more than half in a district that already had a below-average rate of academic growth will be an academic wound that leaves a deep and enduring scar on California and points beyond.

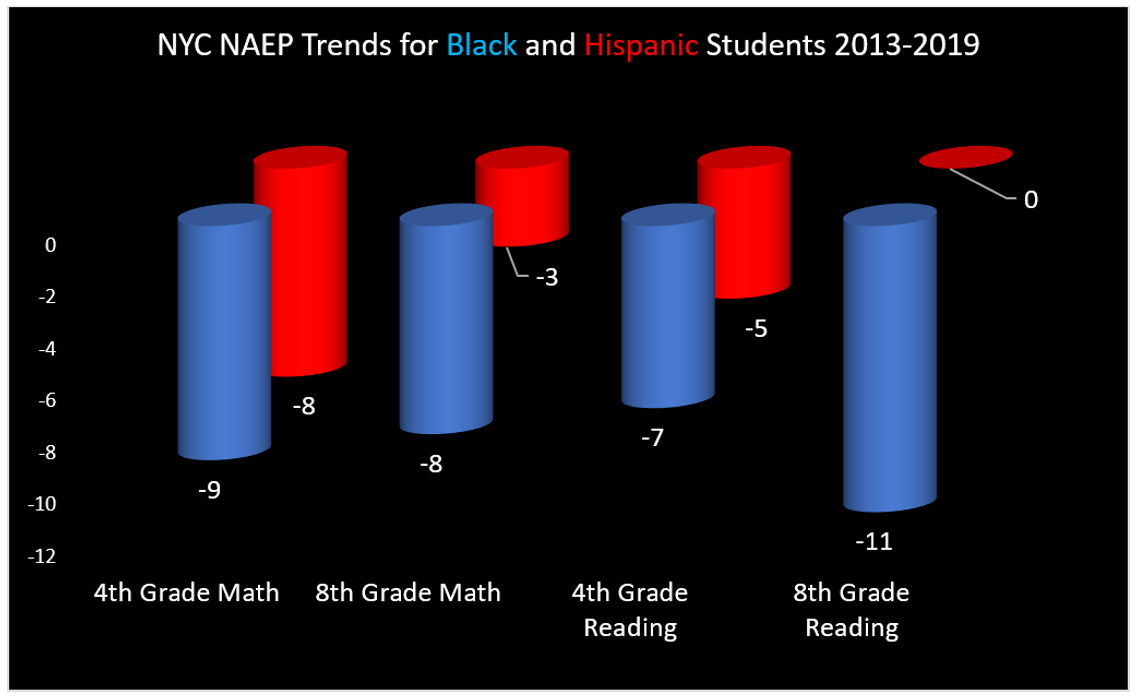

The NAEP Trial Urban District Assessment already had documented a horrific academic disaster in New York City before COVID-19. The chart below shows results for Black and Hispanic students from 2013 to 2019; 10 points approximately equals an average grade level worth of learning.

Humans have survived plagues before. We eventually will recover from this one, but that recovery will come only after a great deal of suffering and long-lasting, self-inflicted damage. False tales of victory have already been written that would make Ramses III blush.

The lesson here is clear: The system takes care of itself as best it can. Taking care of the kids in your family, that’s up to you. If we funded students rather than systems, the next pandemic would go considerably better, and we would have a stronger recovery from this one as well.

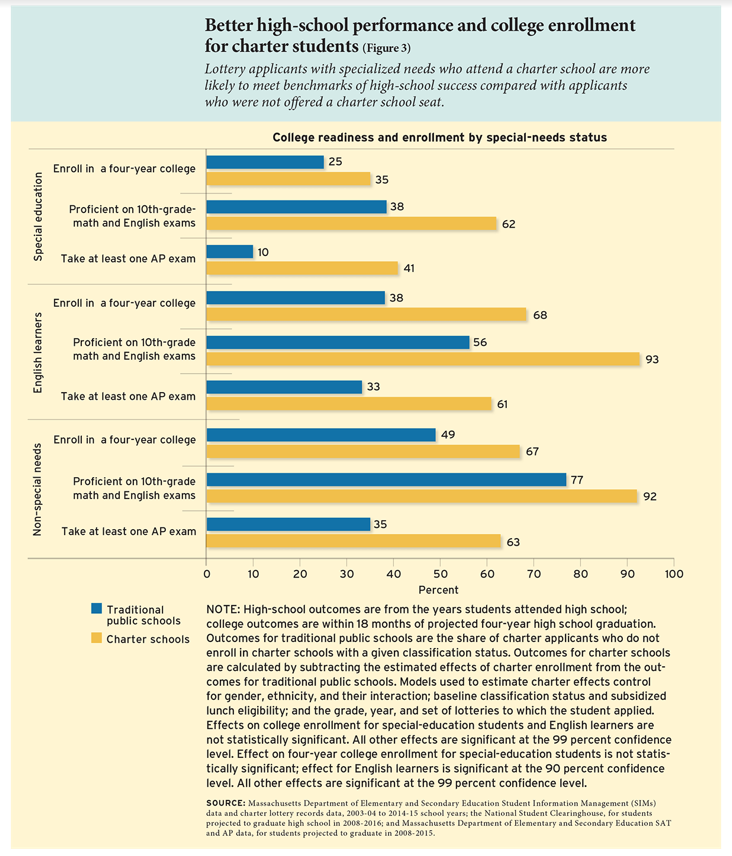

In 2016, Massachusetts voters soundly rejected a ballot proposition (Question 2) which would have allowed 12 additional charter schools per year. A recent study demonstrates how costly this decision has been, especially for special education and English language learner (ELL) students.

In 2016, Massachusetts voters soundly rejected a ballot proposition (Question 2) which would have allowed 12 additional charter schools per year. A recent study demonstrates how costly this decision has been, especially for special education and English language learner (ELL) students.

Tufts University Professor Elizabeth Setren analyzed enrollment lottery data for Boston charters in order to compare long-term outcomes for three groups of students: general education students, special education students and ELL students (see above). The random admission process provides confidence that observed differences in outcomes show the impact of the schools.

Professor Setren noted that the Boston district schools spend significantly more on special education than charters, but charter schools see much better results.

I find that charter enrollment at least doubles the likelihood that a student designated as special education or an English learner at the time of the admissions lottery loses this classification and, subsequently, access to specialized services. Yet charter enrollment also generates large achievement gains for students classified at the time of the lottery—similar to the gains made by their general-education charter classmates.

Classified students who enroll in charters are far more likely to meet a key high-school graduation requirement, become eligible for a state merit scholarship, and take an AP exam, for example. Students classified as special education at the time of the lottery are more than twice as likely to score 1200 or higher on the SAT than their counterparts at traditional public schools. English learners who enroll in charters are twice as likely to enroll in a four-year college.

Students with special education and ELL labels at the time of the enrollment lottery are more likely to discard that status in charter schools. They are also more likely to enroll in a four-year college, score proficient on state exams and take an Advanced Placement course. Notice as well that general education students also see large improvements in those same outcomes.

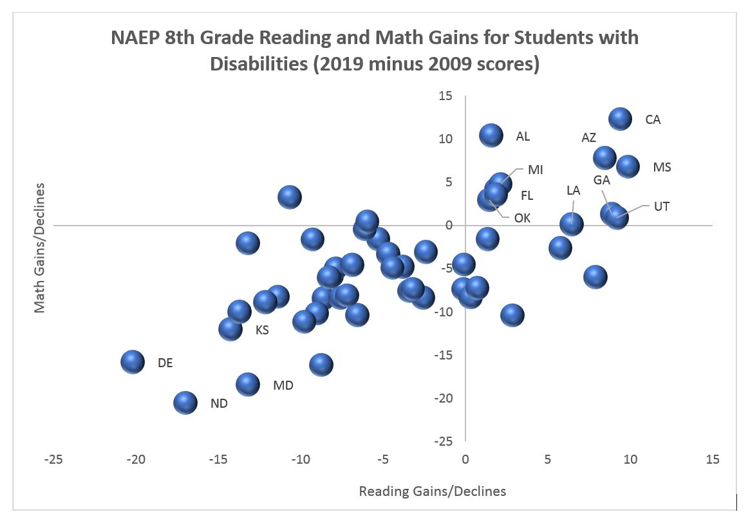

This study seems all the more important given the nationwide decline in NAEP scores for students with disabilities. While there are exceptions, most states saw declines in scores for both eighth-grade math and reading between 2009 and 2019.

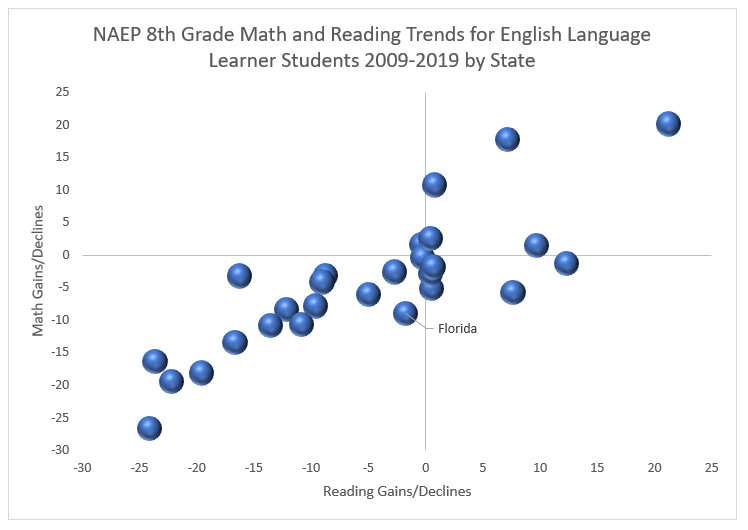

A similar chart for ELL students during the same period looks even worse.

A similar chart for ELL students during the same period looks even worse.

So, Boston charter schools just might have a lesson about high expectations and inclusion. The charter school cap in Massachusetts, meanwhile, is limiting the opportunities for both general and special status students.

So, Boston charter schools just might have a lesson about high expectations and inclusion. The charter school cap in Massachusetts, meanwhile, is limiting the opportunities for both general and special status students.

As a young graduate student, I participated in an exercise that should be routinely practiced in social science training.

As a young graduate student, I participated in an exercise that should be routinely practiced in social science training.

Our statistical methods professor gave us an article published in a top political science journal and provided the same data used by the authors.

Our assignment was to replicate the results. The authors described the methods they used in the article, we despite having the same data, try as we might, none of us could replicate the results.

Our professor had taught us an important lesson about social “science” without having to say it out loud: caveat emptor.

All kinds of things can go wrong in social science research, some errors more innocent than others, so an informed consumer will be looking for results across multiple studies using higher quality methods and from scholars willing to share their data for others to examine. In situations where data is not shared and methods are complex and opaque, the opportunities for mischief multiply rapidly.

Having a press that tends to breathlessly report on studies that confirm pre-existing political narratives is not helpful, as these invariably travel around the world well before there has been time for replication or scrutiny.

This all came to mind recently when I read the following about research claiming to demonstrate that warm weather negatively impacts the academic achievement of students – but only Black and Hispanic students:

In a paper published Monday in the journal Nature Human Behavior, researchers found that students performed worse on standardized tests for every additional day of 80 degrees Fahrenheit or higher, even after controlling for other factors. Those effects held across 58 countries, suggesting a fundamental link between heat exposure and reduced learning.

But when the researchers looked specifically at the United States, using more granular data to break down the effect on test scores by race, they found something surprising: The detrimental impact of heat seemed to affect only Black and Hispanic students.

So, could there be a correlation between climate and student learning?

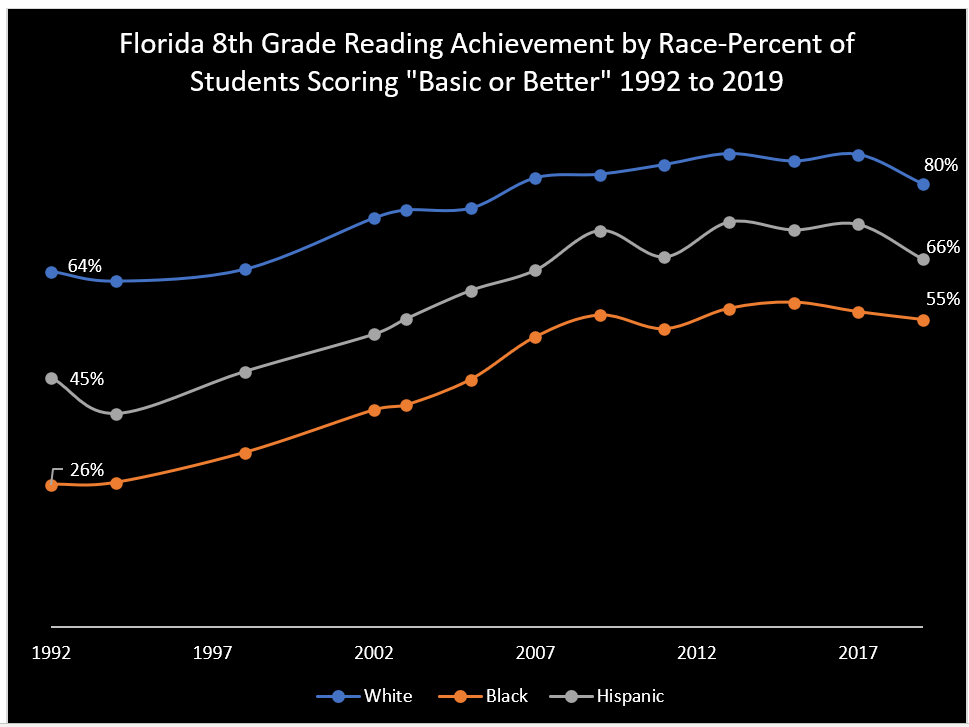

There could be, and there should be more research performed. Do we have reasons to be skeptical? I would say we do. Florida, for instance, gets plenty of days of 80 degree plus weather, but here are the academic trends for White, Black and Hispanic students on NAEP:

That looks a lot like across-the-board improvement to these eyes. The percentage of Florida Black students scoring “Basic or Better” more than doubling between 1992 and 2019 in balmy Florida does not mean there is no role for climate, but it does seem it’s possible to overcome whatever that role may be.

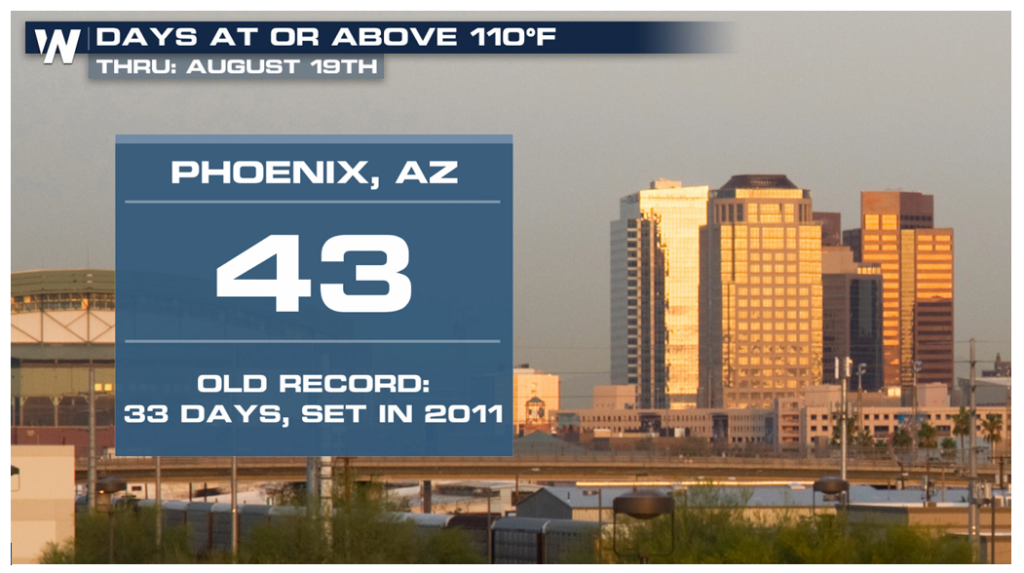

I happen to live in a desert in a state (Arizona) which has a large majority of the state’s students living in Maricopa County, the greater Phoenix area, which is a desert – and a hot one to boot. Stanford University recently compiled data that allows us to compare academic growth rates by county. Maricopa County Hispanic students had an academic growth rate 16% above the national average during the period covered by the Stanford data (2009 to 2016) and Maricopa County Black students were 11% above the national average.

Delightfully, Arizona kids did not get the climate memo either.

Currently, approximately half of white students have access to in-person learning compared to only one-quarter of Black and Hispanic students. A recent analysis of district reopening decisions found politics and teacher union strength to be more influential than COVID-19 trends. The same analysis found that districts with more Catholic schools were more likely to reopen for in-person education.

Luckily for them, in my opinion.

This study, of course, deserves the same sort of scrutiny that the previous one discussed. I fear, however, that we have far more immediate concerns regarding growing achievement gaps than climate change.

If you wanted to determine, tomorrow, if your child was on track in reading or math, where would you turn? What if you wanted to know how your child was doing in a particular math concept, like the Pythagorean theorem?

If you wanted to determine, tomorrow, if your child was on track in reading or math, where would you turn? What if you wanted to know how your child was doing in a particular math concept, like the Pythagorean theorem?

There are some companies that exist for such purposes, like DreamBox Learning, which provides math curriculum, lessons, and formative and summative assessment. But as a regular practice – parents getting outside audits of their child’s understanding of certain subjects and topics, and getting external assessments untethered from the district school system – it is far from the norm.

As I wrote recently in a paper for the American Enterprise Institute, parents should have the resources to obtain regular audits of their child’s learning, and such audits should become commonplace. In the era of COVID-19 learning, this will become more critical than ever.

The National Center for Education Statistics pegs total average per-pupil spending at $14,439 per child in public schools across the country. To get a child from kindergarten to high school graduation costs taxpayers more than $187,000 on average over those 13 years. This is an incredibly costly expense with a high potential for information asymmetry, which can occur when one party has better information about a product or service than another party.

In nearly every other aspect of our lives, such costly investments typically have an associated appraisal market to assure the buyer of the quality of their investment. Yet, no similar market exists for K-12 education. From home appraisals to horse appraisals, external audits of the value of a product provide important information to the end user. We should apply that concept to K-12 education by separating learning assessment from learning delivery.

In normal (non-COVID times), parents largely are recipients of data on public school performance on state assessments, received at the end of the year, providing little information on their child for any necessary education course corrections. They also have access to state- or district-level school report cards, which provide information on the school, not the student.

There also are data from measures such as the National Assessment for Educational Progress (NAEP) that provide state-to-state and some district-level assessments. But while those are useful to education researchers, they are less informative for parents.

For many parents, the most useful information on their child’s progress comes from parent-teacher conferences. Yet these tend to be held infrequently throughout the year. Grades on student homework provide additional information but can be subjective or even inflated.

Teachers may provide information on student progress through portfolios or performance assessments, and schools provide formative and interim assessments. For example, in many schools, parents receive quarterly reports and then report cards at the end of the semester. Some schools also use private assessments, including tests like the PSAT and external assessments for gifted students or English as a Second Language (ESL) exams for non-native English speakers.

And more and more schools are using tools like Schoolology that allow for real-time reporting on student grades. But these evaluations aren't universal and may not always focus on student understanding of discreet concepts.

So, while parents are not entirely in the dark when it comes to how much their children know, they largely do not have day-to-day, actionable information about student progress. Creating an appraisal market for K-12 education could provide immediate, granular information on student performance for parents that is actionable and timely. To do so, states should provide funding for diagnostic and evaluative testing to parents separately from the per-pupil dollars spent on their child in district and charter schools.

When Arizona designed and implemented its groundbreaking education savings account (ESA) program in 2011, they were on to something. Allowing ESA funds to be used for assessments and diagnostic tests, along with the accounts’ other uses (e.g., private school tuition, online learning, special education services and therapies, etc.), was a helpful solution.

As micro-credentials grow in popularity, freeing-up funding in the form of ESAs will enable more students to get specific certifications of learning and knowledge acquisition. ESA-style accounts also enable parents to pay directly for diagnostic tests at testing sites unrelated to the school in which their child is learning.

Making ESAs a reality for every child would enable families to easily acquire real-time, external audits of their child’s learning. And it would likely foster a growth in the supply of such diagnostic tools in the market.

To date, five states – Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee, and North Carolina – have education savings account options in operation, enabling parents to pay for external audits of their child’s learning if they choose. Other states should follow suit. Short of that, states should at least allow parents to leverage a small portion of their child’s state per-pupil funding to pay for assessments and other diagnostic tools.

Information on their child’s progress is a powerful tool. When combined with education choice options, it can be the key to finding options that are the right fit for them, setting them up for success long term.

In the film “The Matrix,” Laurence Fishburne’s character, Morpheus, explains to the protagonist that the world he perceived himself to be living in actually had been a neural computer simulation. Humanity had lost a war against its own artificial intelligence mechanical creations years before. Human beings were grown captive in tanks, kept under control by a system known as the Matrix, and used as batteries.

In the film “The Matrix,” Laurence Fishburne’s character, Morpheus, explains to the protagonist that the world he perceived himself to be living in actually had been a neural computer simulation. Humanity had lost a war against its own artificial intelligence mechanical creations years before. Human beings were grown captive in tanks, kept under control by a system known as the Matrix, and used as batteries.

The film’s final scene and credits roll to a song by Rage Against the Machine called “Wake Up.”

Last week, American Federation of Teachers president Randi Weingarten gave an interview on MSNBC. Host Stephanie Ruhle posed this scenario for Weingarten’s comment:

We know that there are kids living in cities in this country where those cities and those schools are not serving them. If you live in an inner city and you’ve got kids, your best chance for economic mobility for your child is through a great education, and there are schools that are not serving our kids.

Weingarten responded:

And those schools need to get fixed like we did in New York City.

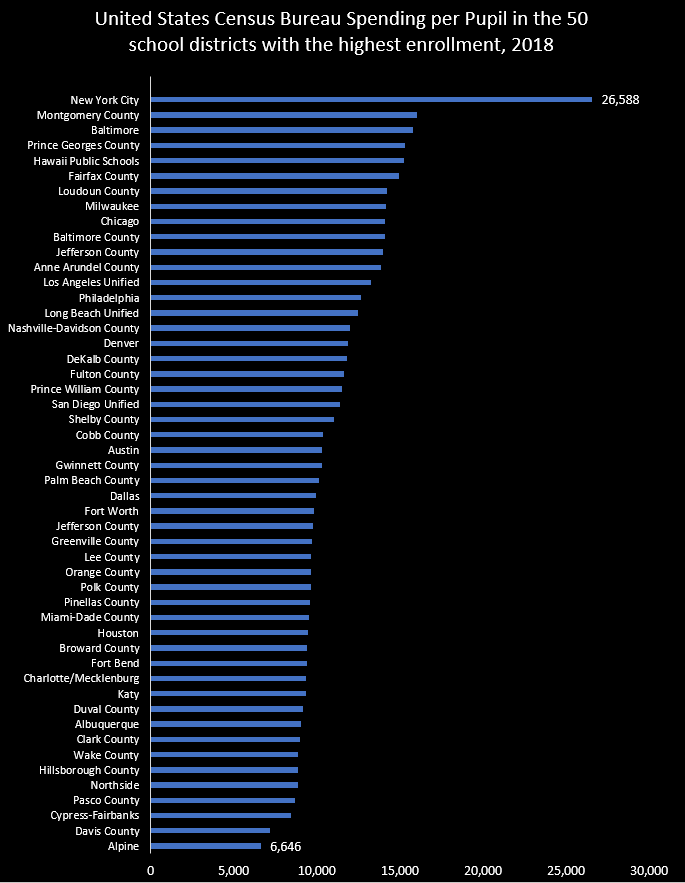

New York City schools may have been “fixed,” but this raises the question, “fixed for whom?”

Weingarten’s organization virulently opposed the education reforms of former Mayor Mike Bloomberg, who left office in 2013. Since 2013, New York City has been run by American Federation of Teachers ally Mayor Bill de Blasio. Have New York City Schools been fixed since 2013?

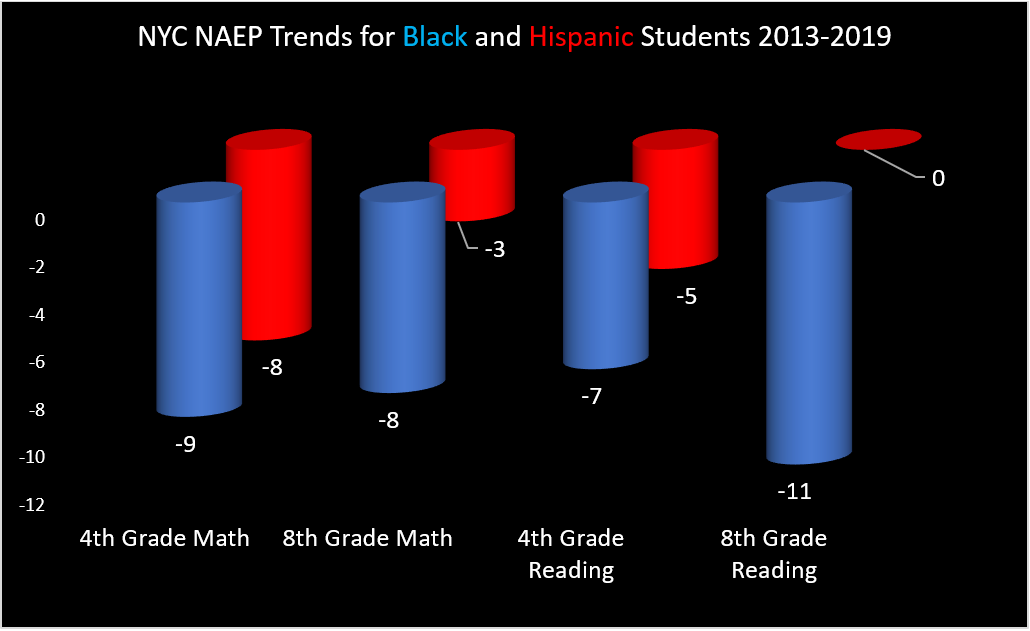

Fortunately, New York City is one of the districts included in the Trial Urban District Assessment of the NAEP. The chart below looks at trends for black and Hispanic students since 2013. On these tests, 10 points approximately equals a grade level’s worth of average progress.

Most of both groups of fourth graders scored “Below Basic” on the 2019 fourth-grade reading exam. The schools clearly are not “fixed” for the sort of students in New York City that Stephanie Ruhle asked Weingarten about in the interview.

In fact, the schools needed improvement in 2013, and then got worse rather than better. If New York City schools have not been fixed for students, for whose benefit have they been fixed? The United States Census Bureau offers a telling clue:

Weingarten’s confusion is understandable, but New York City schools have not been fixed for all students. Rather, they look to have been rigged for her organization and others.

Wake up, New York.

Graduate training in the social sciences teaches students to think in terms of a multi-variable world. Humans naturally gravitate toward simple explanations of reality, such as X caused Y, when in fact isolating the impact of X on Y with reliability is very difficult.

Graduate training in the social sciences teaches students to think in terms of a multi-variable world. Humans naturally gravitate toward simple explanations of reality, such as X caused Y, when in fact isolating the impact of X on Y with reliability is very difficult.

Random assignment studies are the most useful in this regard, but these sorts of studies are difficult and expensive to arrange, and many policies do not lend themselves to random assignment. Many times, we have little choice but to make decisions based upon lesser evidence.

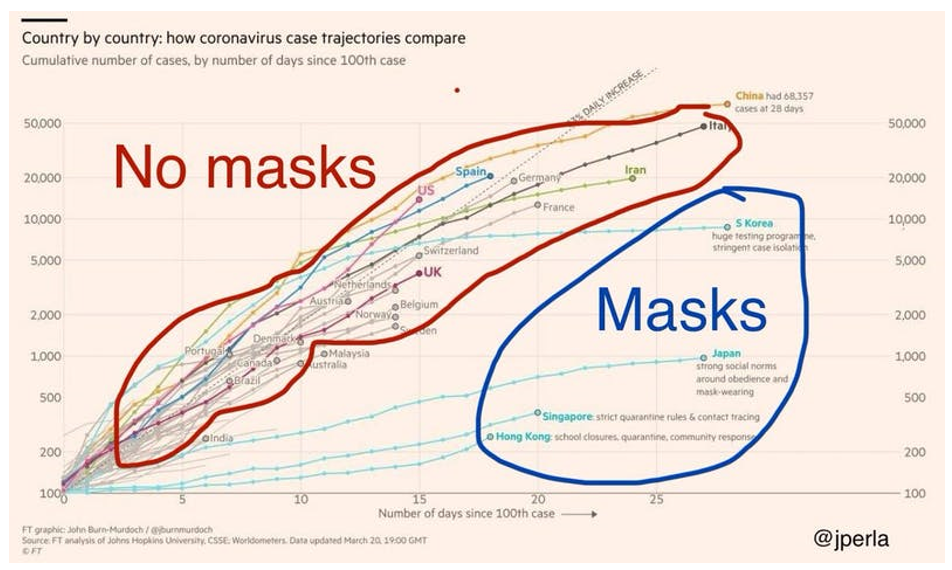

The social scientist is trained to look at technology leader Joseph Perla’s chart above and say, “We shouldn’t assume that South Korea, Japan and Singapore are having a good pandemic because of masks. It could be something else, or it could be multiple other factors. Masks could actually be bad.”

This is all potentially true. Moreover, unless you are willing to randomly assign people to wear masks in public and prevent the control group from wearing them, you cannot know for sure.

Policymakers, on the other hand, do not have the luxury of epistemological nihilism. They must make decisions, almost always based upon incomplete or otherwise imperfect information.

President Harry Truman once said: “Give me a one-handed economist. All my economists say, 'on hand...', then 'but on the other ... ’”

So, while the social scientist looks at this chart and suspects foul play, the pragmatist looks at it and says, “Well, there could be other things going on, and masks could still be playing a positive role.”

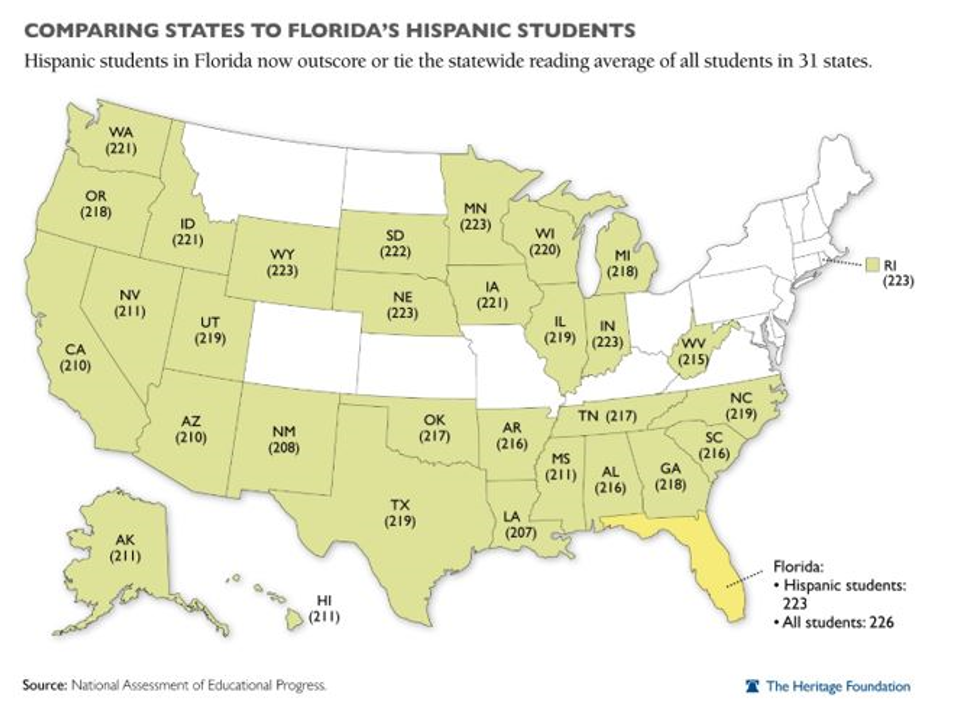

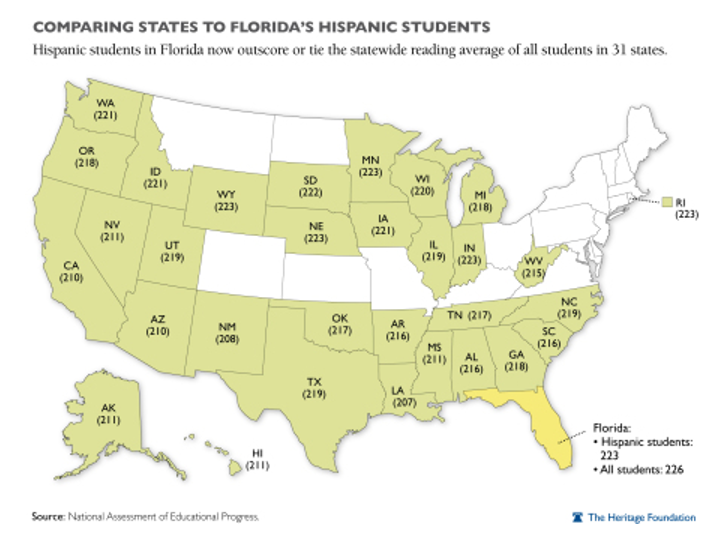

K-12 policy also gets made in a chaotic world with multiple policy changes occurring at the same time. Back when I collaborated with the Heritage Foundation to produce the map below comparing the fourth-grade NAEP scores of Hispanic students in Florida to the statewide averages for students across the country, critics raised the social science objection: “You don’t know which Florida policy led to the increase,” was the essence of the complaint.

This was entirely correct from the point of view of the social scientist, but the pragmatist in me required me to say: “Since we don’t know which of the many reforms in the Florida cocktail led to the improvement, don’t take any chances – implement all of them.”

Likewise, someone might want to study everything Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore have done to prevent the spread of COVID-19. It is not necessarily the same approach. But right about now, encouraging people to wear masks in public is looking like a pretty good idea, not dissimilar from studying a state whose minority students score a grade level higher than your statewide average on reading.

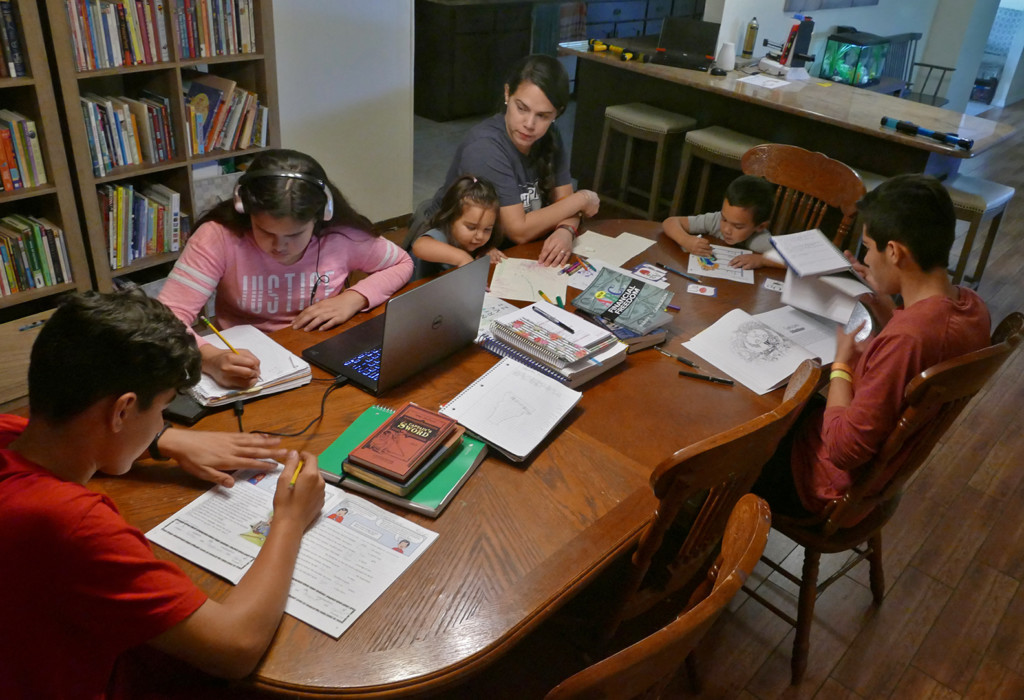

Convinced she could provide her children with all their educational needs, Evelyn Reyes of New Port Richey, Florida, began homeschooling her children eight years ago and realized she could combine education time with family time. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

Editor’s note: This commentary was written expressly for redefinED by Matthew H. Lee, a graduate student in education policy at the University of Arkansas; Angela R. Watson, senior research fellow at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy; and redefinED guest blogger Patrick J. Wolf, distinguished professor of education policy and endowed chair at the University of Arkansas.

“Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive.” -- C.S. Lewis

What prompted Cevin Soling, Freedman-Martin fellow in journalism at Harvard’s Kennedy School, to choose this warning as he introduced an event at Harvard earlier this month?

The “tyranny sincerely exercised” is the presumptive ban against homeschooling that Harvard Law professor Elizabeth Bartholet recommends in her recent Arizona Law Review article, “Homeschooling: Parent Rights Absolutism vs. Child Rights to Education & Protection.”

Her proposed ban puts parents “ideologically committed to isolating their children” on trial and assumes their guilt for denying “their children any meaningful education” and subjecting their children to “terrifying physical and emotional abuse.” It shifts the burden of proof to the accused to “demonstrate they would provide a significantly superior education.”

What happened to a presumption of innocence before the law?

Far from Bartholet’s accusations, homeschooling is not a small, monolithic practice dominated “overwhelmingly” by conservative Christians. At any given time, homeschoolers make up roughly 3 percent of the school-age population, and one study published in the Peabody Journal of Education estimates that as many as 10 percent of all American students are homeschooled at some point during their academic careers.

A 2019 Center for Reinventing Public Education report finds the most rapidly growing homeschooling subgroups are people of color. Another report published in the Peabody Journal of Education noted that “The phenomenon of increasing black home education represents a radical transformative act of self-determination, the likes of which have not been witnessed since the 1960s and ‘70s.”

Meanwhile, National Center for Education Statistics data show that homeschool respondents are more concerned with the “environment of other schools” and “academic instruction” than they “desire to provide religious instruction.”

A presumptive ban against homeschooling denies at least two rights. First, it denies parents the right to govern the education of their child, proclaimed by the US Supreme Court to be their fundamental right in 1923 (Meyer v. Nebraska), 1925 (Pierce v. Society of Sisters), and 2000 (Troxel v. Granville). Second, by giving public officials the authority to conduct home visitations in homeschooling households and to forcibly enroll children in public schools against their parents’ wishes, it denies both parents and children the right to be secure in their persons and homes against unreasonable searches and seizures.

Let’s shift the burden of proof back to homeschooling’s accusers. Can they prove that public schooling delivers better academic results, strengthens democratic values and provides a surer guarantee against abuse than homeschooling?

Homeschooled children demonstrate academic outcomes equal to or better than their public-school counterparts. While we don’t know about academic outcomes for all homeschooled students, a 2010 report by Brian Ray finds that homeschoolers on average score between 15 to 30 percentage points above the national average. As for those who pursue a college education, a review by Gene Gloeckner and Paul Jones indicates that when differences are detected, homeschooled students have higher standardized test scores and college GPAs relative to their public school peers.

Homeschoolers also compare favorably to publicly schooled students on civic and democratic values. Research by Albert Cheng of the University of Arkansas finds homeschooling is associated with more political tolerance relative to public schooling. Indiana University’s Robert Kunzman reports a similar advantage in his 2009 book, “Write These Laws on Your Children: Inside the World of Conservative Christian Homeschooling.”

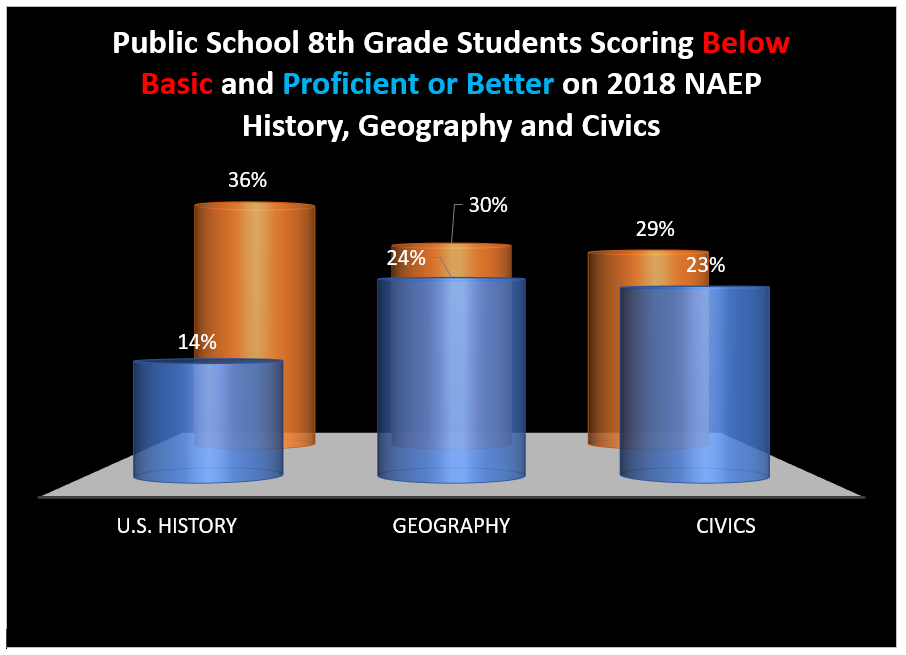

As for public school students, according to the 2018 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Civics Assessment, only 24 percent of U.S. eighth-graders perform at or above NAEP “Proficient” on civics.

Finally, even public schools cannot provide an absolute guarantee against abuse. In 2004, the US Department of Education estimated that one in 10 public school students will be sexually assaulted by a public school employee by the time they graduate. While abuse anywhere is unacceptable, a presumptive ban against homeschooling assumes parents are guilty of abusing their children until proven innocent while unrealistically assuming public school personnel are always innocent of such horrible transgressions. Unfortunately, they are not.

In delivering the opinion of the Supreme Court in the 1925 case Pierce v. Society of Sisters, Justice James McReynolds wrote, “The child is not the mere creature of the State; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.” Homeschooling may be the purest expression of families exercising this right and rising up to meet this high duty.

As courts have ruled repeatedly, when homeschooling is put on trial and given due process, a fair reading of the evidence gives us no choice but to emphatically declare, “Not guilty!”

K-12 choice programs began as a proposal by a Nobel Prize-winning economist to improve K-12 outcomes. Could other mechanisms devised by economists in other policy areas, such as cap-and-trade policies to reduce air pollution, also improve K-12 outcomes?

K-12 choice programs began as a proposal by a Nobel Prize-winning economist to improve K-12 outcomes. Could other mechanisms devised by economists in other policy areas, such as cap-and-trade policies to reduce air pollution, also improve K-12 outcomes?

The answer might be yes in theory, but in practice, probably not.

In a cap-and-trade system designed to reduce pollution, the government sets an emissions cap and issues a quantity of emission allowances consistent with that cap. Emitters must hold allowances for every ton of greenhouse gas they emit. Companies may buy and sell allowances, and this market establishes an emissions price. Companies that can reduce their emissions at a lower cost may sell any excess allowances for companies facing higher costs to buy.

Under a cap-and-trade regime, firms get an allowance for the amount of pollution they can emit, and when they reduce their pollution above and beyond their goal, they benefit by being able to sell some of their “pollution allowance.” This creates a financial incentive for all firms to reduce pollution. Those who exceed their goals receive payments; those who do not reduce pollution must either get used to paying other firms or figure out a way to their own pollution down.

Andrew McAfee of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology notes in his book More From Less that cap and trade has been a huge success. While it takes some time to wrap one’s head around the idea of allowing companies to sell the right to pollute the atmosphere (a notion that one’s instinct naturally seeks to reject), cap and trade has been enormously more successful at reducing pollution than clumsy top-down fiats.

A cap-and-trade mechanism can create an incentive for all polluters to become innovators and to seek the lowest cost methods for reducing as much pollution as possible. McAffee reports a 2009 Smithsonian summary that found a cap-and-trade program cost only a fraction of an initial estimate ($3 billion instead of $25 billion) and generated an estimated $122 billion in health and environmental benefits. If one assumes the actual benefits were only half that amount, it still represents an impressive 20 to 1 return on investment.

Cap and trade in effect creates a quasi-market for pollution reduction. Could state lawmakers create such a scheme to reduce, say, early childhood illiteracy?

The technical challenges would be considerable, perhaps insurmountable. Cap-and-trade schemes must lay out their scope (what exactly is to be reduced), create an overall target for reduction, figure out the gritty details of exchange and ensure market integrity. The details matter in each case: How do you set the cap, how do you measure, over what period do you measure?

We will lay out a theoretical example in which Florida lawmakers set a cap for third-grade illiteracy below.

Market integrity would represent a large challenge. The incentive to pretend to reduce pollution under a cap-and-trade scheme is even stronger than the incentive to reduce pollution if firms can get away with it. If the goal were to reduce illiteracy, something much more credible and secure than a set of self-administered exams would be entirely necessary. Let us assume a set of third-party administered exams like the SAT and ACT could be worked out.

In 1998, 48 percent of Florida fourth graders scored “Below Basic” on the NAEP fourth-grade reading test. On the most recent exam, 30 percent scored “Below Basic.” That is an impressive reduction compared to other states, but it will not be hitting single digits anytime soon.

If market integrity could be assured, the state could set a fourth-grade illiteracy cap of 25 percent and make assignments to either schools or LEAs consistent with that goal based upon their previous performance and let the educators figure out how to get it done. Those who succeed in exceeding their target would be rewarded. Those failing to meet their cap would need to buy credits with their set-aside funds from schools or LEAs that exceeded their credits.

How would they do it?

If the cap-and-trade market were established, we cannot know in advance what methods might arise to reduce illiteracy. Some might make much greater use of Reading Scholarship Accounts, others virtual education, but there is just no telling what Florida educators might come up with.

Should we give it a try?

No, I do not think so. While cap and trade is a fascinating institution to harness market forces for social goals, education policy is fashioned democratically rather than technocratically. Given the delicacy of a whole series of decision points under cap and trade, it is hard to imagine that opponents of the policy would find easy work in fouling the gears even if it were in fact attempted. Unlike education choice policies, which develop a constituency, many of the families attending schools selling illiteracy credits in a cap-and-trade scheme would likely remain unaware of the fact. Meanwhile, schools lacking confidence in their ability to hit targets likely would quickly organize into a seek-and-destroy cap and trade faction.

The handful of districts that have attempted portfolio models struggle with similar challenges. While in theory any district in America could conduct a competition for the right to run their schools from groups of educators, few have done so in practice, and fewer still have persisted in it. It is not impossible, just very difficult politically.

K-12 cap and trade would be even more difficult. Education choice policies have the virtue of developing a supportive constituency to defend new freedom, which makes it the most politically plausible method for utilizing voluntary exchange and association to better serve public purposes.

Diffusion, then, rather than discovery, is the duty of our government. With us, the qualifications of voters are as important as the qualifications of governors, and even comes first in the natural order. -Horace Mann

Diffusion, then, rather than discovery, is the duty of our government. With us, the qualifications of voters are as important as the qualifications of governors, and even comes first in the natural order. -Horace Mann

Preparing students to responsibly exercise citizenship represented a foundational aspiration in the founding of the American public-school system. Then as now, we did not simply aspire to have schools equip students with the knowledge and skills necessary for economic flourishing; we also wanted students to develop a grounding in history and civics.

Our education system is failing to accomplish this goal.

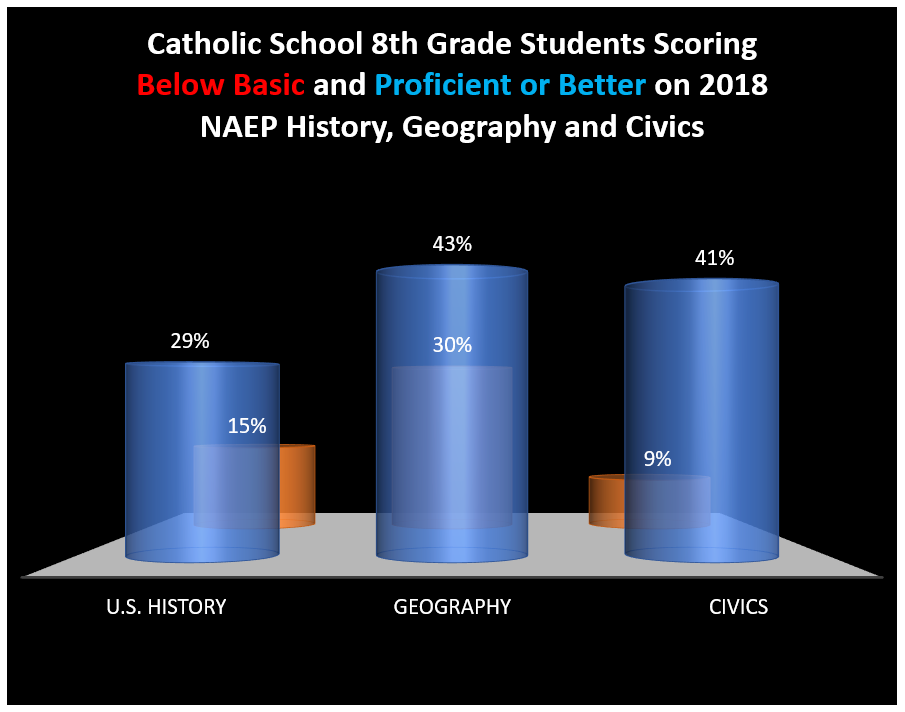

Last week, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) released nationwide eighth-grade data on the 2018 exams taken in United States History, Geography and Civics. Fewer than one-third of American public-school students scored proficient on any of the three exams. In fact, on each exam, the percentage of public-school students scoring “Below Basic” exceeded the percentage scoring “Proficient.”

For every eighth-grade public-school student who scored “Proficient,” there were more than 2.5 who scored “Below Basic,” the lowest achievement level. We can’t be sure what the ratio of “Proficient” to “Below Basic” would be among American eighth-graders if we abolished their history classes, gave them a library card and offered to pay them a dollar for every history book they read, but it might surpass 2.5 to 1.

While scores aren’t available for private schools in general, scores for Catholic school students are – and they tell a different story.

Scores of Catholic school students show an advantage, in several ways: when comparing them to free and reduced-price lunch-eligible public-school students; non-eligible free and reduced-price lunch populations; and racial and ethnic groups. If you compare Catholic school students of parents without college degrees to public-school students of parents without college degrees, Catholic school students get the better of it. The same holds true when you compare Catholic school students of college-educated parents to public-school students of college-educated parents.

Ironically, we heard last week a faint echo of the Know-Nothing Party’s anti-Catholic school rhetoric directed at home schooling. Harvard Magazine quoted Harvard Law professor Elizabeth Barthole:

“From the beginning of compulsory education in this country, we have thought of the government as having some right to educate children so that they become active, productive participants in the larger society,” she says. This involves in part giving children the knowledge to eventually get jobs and support themselves.

“But it’s also important that children grow up exposed to community values, social values, democratic values, ideas about nondiscrimination and tolerance of other people’s viewpoints,” she says, noting that European countries such as Germany ban homeschooling entirely and that countries such as France require home visits and annual tests.

People can have honest disagreements about home-school policy, but I invite the reader to ponder the first chart in this post and attempt to square it with the quote above. Should we be worried about the civic values and knowledge of the 3 percent of students who home-schooled before the pandemic? Or might the appalling lack of history, geography and civics displayed by the 87 percent or so students attending public schools constitute a more pressing concern?

You, dear reader, look as though you could use some distraction from the viral apocalypse. Like many good stories, this one flashes back to the past to inform the present.

You, dear reader, look as though you could use some distraction from the viral apocalypse. Like many good stories, this one flashes back to the past to inform the present.

A decade ago, while an analyst at the Goldwater Institute, I participated in a debate concerning choice versus curriculum reform. Yes, people were confused about whether those things were mutually exclusive a decade ago, as they are today. (Spoiler alert: choice helps curriculum reform).

In any case, the debate prompted me to ask myself which states had done a lot of both choice and testing accountability. This in turn led me to look closely at the NAEP scores of Florida and to consider that former Gov. Jeb Bush had aggressively sought to improve literacy instruction by creating a variety of public and private choice mechanisms.

Staring at fourth-grade NAEP scores by race/ethnicity on my computer screen, here is what I discovered.

The conversation around K-12 in Arizona at the time frequently involved an “if you control for student demographics, we are kind of average” story. This was part of a fable with a thousand faces; you will hear different versions of it in different states. In Arizona, the story involved kids immigrating from Mexico who were unable to read Spanish. In Minnesota, I’ve heard tales told in hushed voices about Hmong kids. In more than one southern state, I’ve heard allusions to scores of white kids scoring quite high when they weren’t anything of the sort. The details vary, but the moral is always the same: “We here in state X, we’ve got the really hard-to-educate kids.”

The fact that Florida’s Hispanic students were reading approximately a grade level higher than the average for all students in Arizona required the development of a new rationale. That new rationale was the magic Cuban theory. Florida’s Hispanics are Cubans, the story went, and they are wealthy. “Obviously we can’t expect to do that with our Hispanic students,” the theory concluded.

I related the magic Cuban theory to an audience at the first ExcelinEd conference held in Orlando. Given the advantage of local knowledge held by many audience members, the crowd laughed out loud at the absurdity of the stereotype. Despite living in a distant patch of cactus, I had spent enough time in the Florida Keys with my grandfather to develop a lifelong taste for ropas viejas and to know better.

The magic Cuban theory could never survive scrutiny. First off, Florida’s Hispanic community is vastly more diverse than appreciated by distant stereotypes, with Cubans constituting a minority among Hispanics. Second, Florida saw large increases in literacy among multiple ethnic groups. Magic Haitian theory anyone?

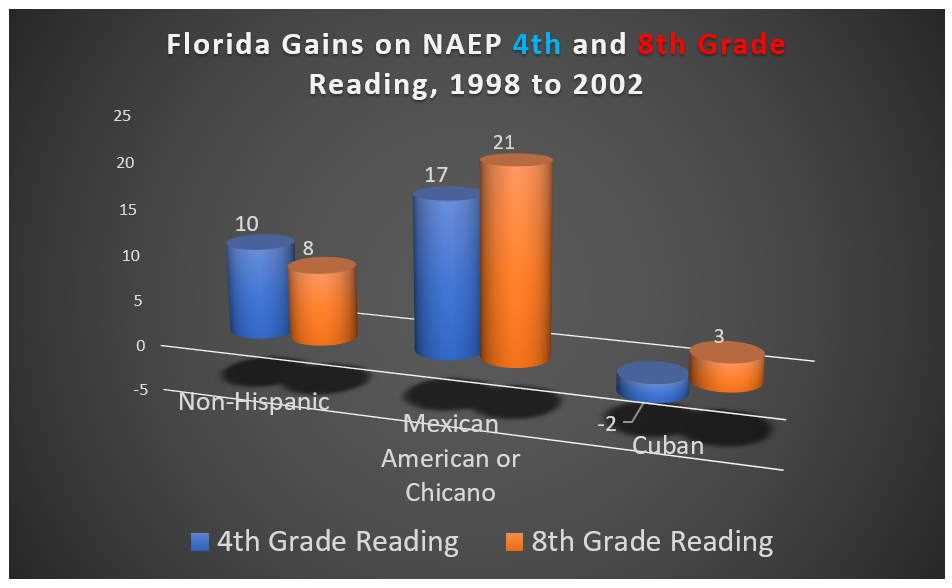

Finally, buried deep in the data explorer, NAEP has a variable that allows you to break down Hispanics by subgroup. NAEP, alas, discontinued this variable, but we do have it for both 1998 (the year before Jeb Bush took office) and 2002. It would have been great to have data from additional years, but note that the 2002 NAEP came before the adoption of the third-grade retention policy. Between 1998 and 2002, Florida policymakers had adopted major education reforms, but not all the reforms.

Here is what the gains looked like during the 1998 to 2002 period.

Florida’s Cuban-Americans scored well, but they were not driving gains. As a rough rule of thumb, 10 points on NAEP exams approximately equals an average grade level’s worth of progress. In other words, we would expect a group of fifth-graders given the fourth-grade test to do about 10 points better. The Mexican-American gains were very large, very meaningful and very statistically significant.

By the way, those eighth-graders from 2002 are approaching their mid-30s now. With all of today’s troubles, and considering those around the bend, Florida chose wisely in not succumbing to the soft bigotry of low expectations, instead making an all-out effort to teach literacy. Life is hard, but life is really hard if you can’t read.