Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed an executive order recently to transition the state away from the current academic standards, which begs the question: What will replace them? I have a suggestion on that front, but first, some basics.

Federal law requires states to have a set of academic standards and to test students against those standards in grades 3-8 and again in high school as a condition of federal funding. About a decade ago, a number of states adopted “Common Core” academic standards and tests, which eventually became quite controversial. As an education reform strategy, both center-right analysts like Erik Hanushek and center-left analysts like Tom Loveless found little prospect for broad improvement in outcomes due to adoption of the standards.

In fact, if we examine eighth-grade trends in scores since 2009, just before many states adopted the standards, to the most recent numbers, the results are decidedly less than meh, although multiple factors always are at play in influencing scores at any given time. While “meh” results square with the Hanushek/Loveless research findings, this does not preclude the possibility of states doing themselves some harm in transitioning to new standards.

Practices eliciting a great deal of controversy for ambiguous benefits don’t tend to endure. The theory of change behind the standards movement seems straightforward: States create (hopefully) an integrated set of academic standards, test students against those standards, make the results transparent to families, and perhaps reward/sanction schools based on them. If in fact it were this straightforward, we would expect to see broad improvement in a variety of academic indicators since the adoption of the strategy in the mid-1990s. But the theory-of-change bucket seems leaky. Meanwhile, much of the public has grown deeply fed up with a culture of test prep in public schools.

Supporters of academic transparency – I include myself in this category – ought to use this opportunity to consider carefully what it is we want from our system of standards and tests, how to minimize unintended consequences, and how to increase the utility of the system to students. Federal law requires states to have them, so why not adopt the best standards that any state has developed?

Massachusetts was a pioneer in the standards movement, creating standards almost a decade before the federal requirement. Massachusetts also adopted several other K-12 reforms simultaneously, so we should exercise caution in concluding that standards and testing led to the state’s improvement. Nevertheless, those standards were widely admired by scholars. Even prominent supporters of the Common Core project judged them superior to the Common Core standards.

Massachusetts has long held the highest scores in all subjects on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. We can’t be certain what they did right, but they seemed to have done something right, and it might be the standards. The reality is that there would be a large amount of overlap in a three-circle Venn diagram between the old Florida standards, the more recent Florida standards, and the old Massachusetts standards. Massachusetts may, however, have succeeded in positively influencing curriculum with its standards, which have been described as “content rich.” Color me skeptical as to whether there is either a Florida, Arizona or even (blasphemy!) Texas way to teach long division, but Massachusetts seemed to do better than others with its old standards, and in fact better than itself after adopting Common Core.

There is no issue of federal nudging or compulsion, real or imagined, at this point. Florida is entirely free to adopt whatever standards it wishes. You won’t find many areas of agreement between me and Diane Ravitch, but I think this qualifies as one: You must have standards, and Massachusetts has developed what appear to be the most useful set. Why settle for less?

My advice, not that you asked for it, is to call up the Bay State and see if anyone there can send over a copy.

The dissent’s cursory review of faulty education data in Citizens for Strong Schools v. State Board of Education could have deprived many Florida families of educational choice.

Do vouchers and charter schools harm public schools, thereby violating the state’s constitutional duty to fund an adequate system of uniform public schools? Until last month’s 4-3 decision in Citizens for Strong Schools v. State Board of Education, the Florida Supreme Court had ignored the empirical question entirely. In Bush v. Holmes (2006), the court majority decided that a theoretical harm, real or not, was enough to declare the Opportunity Scholarship Program unconstitutional.

The three dissenting justices in Citizens for Strong Schools, who all decided on Bush v. Holmes 13 years earlier, finally were forced to examine the evidence. Unfortunately, the dissent’s cursory review of education data focused on some bad statistics. One more vote and shoddy data could have spelled the end of educational options for more than 425,000 children in the Sunshine State.

The dissent prominently featured a USA Today article that ranked education by state.

The article was compiled from Education Week’s Quality Counts “overall” 2017 ranking. That ranking used multiple statistics: graduation rates, public school spending, eighth-grade proficiency in the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), adults with a bachelor’s degree or above, and the percentage of adults in the state with incomes above the national median.

The ranking is severely flawed for several reasons:

During the trial, lawyers for the Florida Department of Education argued that Florida’s K-12 outcomes were superior to that of New Jersey, a state that lost a funding adequacy lawsuit in 1985 and was forced by the court to greatly increase spending for students in high-poverty school districts.

The dissent pointed to the USA Today article and noted that New Jersey ranked No. 2 while Florida ranked No. 29. But as stated above, the overall USA Today/Education Week ranking biases in favor of wealthier and whiter states, like New Jersey.

Digging deeper into the data, we find that Florida has a larger minority population with black and Hispanic students making up 54 percent of the student body, compared to 42 percent in New Jersey. When comparing NAEP eighth-grade reading and math results, Florida tends to do just as well as New Jersey for black, Hispanic and low-income student populations.

The fact that New Jersey’s low-income districts spend nearly three times as much as Florida and achieve the same results on eighth-grade NAEP tests is telling. If New Jersey is high quality, as the dissent insists, then so, too, is Florida.

Contrary to the insistence of some critics, the court majority correctly rejected the power to determine “adequate” K-12 spending based on platitudes like “efficient” and “high-quality.” The majority also recognized the complexity of education statistics and rejected the argument that school choice makes Florida’s K-12 system perform poorly. In fact, the court recognized that these programs may have a positive effect on public schools.

Whether public schools should be better funded is another story entirely. It’s a debate we should continue to have, but you just can’t use bad statistics to throw Florida’s entire K-12 system, including school choice, under the bus to make your case anymore.

My new year’s resolution is to do a better job explaining myself as a choice supporter. There is apparently a need for this, as evidenced by this recent Tampa Bay Times editorial piece about key players in Tallahassee in 2019. Regarding Florida’s new education commissioner, the Times opined:

Richard Corcoran

The answer to every education conundrum in Florida is not either (a) charter schools or (b) vouchers. In fact, new Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran should remember most students attend traditional public schools, that the state Constitution guarantees a “high quality system of free public schools,” and that his first order of business should be strengthening those schools, not scheming to tear them down or replace them.

This statement could be critiqued in a variety of ways, but today I’ll attempt to demonstrate that expanding educational opportunities however represents a strategy to in fact achieve a “high quality system of free public schools.” Furthermore, it seems to be working.

Florida created the nation’s first choice program for students with disabilities in 1999 with the McKay Scholarship Program. Students with disabilities have had the option of applying for a scholarship to attend a different public or private school statewide since 2001. Rather than representing a scheme to “tear down or replace” public schools, the statewide performance for students with disabilities improved faster than the national average. Florida lawmakers (wisely) further expanded options for students with disabilities in 2015 by creating the Gardiner Scholarship Program-the nation’s second Education Savings Account program.

This seems to be working out relatively well for Florida students with disabilities, the vast majority of whom continue to attend district schools. For you incurable skeptics, things pretty much look like Florida and the 49 dwarves when it considering both gains and overall scores for students with disabilities:

And reading:

Students with disabilities in Florida public schools have had access to full state funded choice since 2001. Students with disabilities have also had access to the other forms of choice-charter schools, the Florida Virtual School, that all Florida students can access, but in addition to that, they have had the option of attending a private school with the state money following the child. The Florida tax credit program provides opportunities for low-income students but is limited by the amount of funds raised and has a waitlist. Florida’s students with disabilities have had the most robust set of choice options for the longest period.

When we compare the gains of student with disabilities (and the fullest access to choice programs) to students without disabilities on all the NAEP exams given consistently since 2003 it looks like this:

Ten points approximately equals an average grade level worth of progress on these NAEP exams (for instance we’d expect a group of 9th graders to do 10 points better than they had as 8th graders). The technical term to describe those red columns: HUGE! In fact, if Florida’s statewide gains had matched those of students with disabilities since 2003, Florida would have matched or beat NAEP champion Massachusetts on all four NAEP exams in 2017.

Impossible you say? Many would have said those academic gains for students with disabilities were impossible in 2003, nevertheless they happened.

A new analysis by Reason magazine of Florida's public education system shows that, when focused on actual academic outcomes, the rhetoric of the system being in crisis again does not match the reality.

Is Florida’s public education system as bad as many of its critics suggest? Yet another analysis, focused exclusively on actual academic outcomes, says no. In fact, according to Reason magazine, Florida ranks No. 3 in K-12 educational quality and No. 1 in educational efficiency.

Released this week, Reason’s ranking based on outcomes isn’t that far off from Education Week’s ranking based on outcomes. Last month, Education Week ranked Florida No. 4 in the nation in “K-12 Achievement.”

Reason’s ranking relied on reading, math and science scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), also called “The Nation’s Report Card.” Education Week’s achievement ranking is based on NAEP reading and math scores; results on Advanced Placement exams; and graduation rates.

Education Week ranks states on three categories: “Chance For Success,” “School Finance,” and “K-12 Achievement.” These categories are compiled to produce an overall ranking. While Florida ranks No. 4 on K-12 Achievement, according to Education Week, the inclusion of the other categories drops the Sunshine State’s overall ranking to No. 29.

Other outlets, like U.S. News, also use data besides academic outcomes to determine rankings. The Reason study’s authors, Stan Liebowitz and Matthew L. Kelly, are not fans of this approach. They’re also not fans of using raw NAEP data without consideration for racial demographics, which they call “misleading.”

The combined methodological flaws lead to questionable, if not misleading, overall rankings, they write. (more…)

We can’t have honest dialogue about the what needs to be fixed in Florida's education system without an appreciation for the signs that academic outcomes are trending upward.

The recent Education Week report that ranked Florida public schools No. 4 in the nation in academic achievement was well-deserved recognition for this state’s underappreciated schools. It arrived in the thick of an election season where public education has been front-burner. And, given the less-than-glowing reputation of Florida’s education system, it bore all the markings of a flying pig. Florida No. 4 in academics?! Stop the presses!

Yet in a state with 21 million people, only one media outlet covered it.

On the flip side: Last week, another report found Florida to be the fifth-worst state to be a teacher. This report wasn’t compiled by seasoned, knowledgeable education journalists, like those who work at Education Week. Rather, it was crafted by WalletHub.

To date, eight news outlets have covered the WalletHub report, including three papers that editorialized about it.

For the sake of argument, let’s say the ranking methodologies from EdWeek and WalletHub are equally rigorous. Let’s agree we’re all guilty of confirmation bias. Even then, I have to ask my reporter friends: Does this seem right?

I’m a journalist by training. I had my first byline when I was 18. I worked at newspapers my entire adult life before I joined Step Up For Students (which publishes this blog) six years ago. For eight of those years, I covered education at the biggest paper in Florida, during a period of particularly heady change.

So don’t count me as another media grump. But I struggle with the degree to which news coverage in Florida seems to be missing powerful indicators of progress in public education. And I fear that the absence of such reporting has contributed to a warped public debate.

We can’t have honest dialogue about funding, testing, teacher pay, vouchers, charter schools, accountability – any of it – without an appreciation for the signs that academic outcomes are trending upward.

Consider another example. (more…)

Florida public schools now rank No. 4 in academic achievement, behind only Massachusetts, New Jersey and Virginia, according to the latest annual “Quality Counts” report from Education Week, released this week. Though it’s not noted in the report, Florida has a far higher rate of low-income students than any state in the Top 10, with roughly 60 percent of its students eligible for free- and reduced-price lunch.

The latest ranking is Florida’s highest ever. But it shouldn’t come as a surprise.

In fact, it punctuates a decade-long run.

Since 2009, Florida has, by Education Week’s analysis, finished at No. 7, No. 7, No. 6, No. 12, No. 12, No. 7, No. 7, No. 11, No. 11 and now No. 4. (The rankings stayed the same in some consecutive years because Education Week waited on national test scores, released every other year, to re-calculate.)

Education Week bases its analysis on a combination of common indicators: high school graduation rates; results on college-caliber Advanced Placement exams; and reading and math scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, considered the gold standard of standardized tests. It factors in proficiency and progress.

In a less tribal world, yet more good news about the relative performance of Florida public schools would finally knock the dunce cap off the state’s reputation, and spur more scrutiny of those trying to keep it there. The track record there isn’t encouraging.

Florida’s vision of education reform has been in the state and national spotlight for 20 years and remains “controversial” despite the rising trend lines. State policy makers have consistently emphasized a dual approach: Tough regulatory accountability measures like school grades. And an expansion of school choice options like charter schools and private school scholarships.

The latest news will come as a surprise to many parents – if they hear it – given the still oft-repeated myth that Florida schools are sub-par.

Twenty years ago, Florida’s education system was anemic, according to the most common indicators, with barely half its students graduating. But today, Florida’s public schools have never performed better, according to the same indicators. In some respects, they are among the best in the nation.

For example, Florida students rank No. 1, No. 1, No. 3 and No. 8 on the four core NAEP tests, once adjusted for demographics, according to the left-leaning Urban Institute. After the latest round of NAEP scores were released last spring, showing Florida had made the biggest gains in the nation, a top official at the National Center for Education Statistics told reporters, “Something very good is happening in Florida, obviously.”

Obviously.

How odd, then, that some who define themselves as public school defenders continue to double down on the notion that Florida public schools are being decimated – and to blame school choice for a decimation that so clearly isn’t happening.

How odd, too, that they so easily get away with it.

A few months ago, the latest results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress – the gold standard of standardized tests – showed Florida, again, made a national splash. This time, it notched the biggest gains in America.

Florida now ranks No. 1, No. 1, No. 3 and No. 8 on the four core tests on The Nation's Report Card, after adjusting for demographics.

You’d think the biggest gains in America would prompt applause from school boards, superintendents, teacher unions, and allied lawmakers. But no. In Florida, good news about public schools is increasingly ignored by public school groups; media coverage is mostly crickets (recent exception here); and alternative facts seed conspiracy theories.

No wonder, then, that plenty of candidates for political office are again vying to see who can flog the system the most. One gubernatorial candidate says “we are experiencing a true state of education emergency,” citing a single, obscure (at least in education circles) ranking, based on an especially crude set of indicators. Another says “Florida’s education reform has been a failure” while citing no evidence at all.

Deny and distort. Refuse to acknowledge progress. Demonize anybody who does. This is what “debate” over Florida education has come to.

Measures like NAEP scores continue to show the system is not only better than ever, but, in some ways, among the best in America. Yet to many, it’s still Flori-duh.

The tragic result is Florida teachers don’t get credit they deserve. And every day Floridians have no idea their public schools are on the rise.

Consider:

We've written before about the improving results in Miami-Dade County Public Schools, and the potential for improvement in Duval County.

The latest results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress show those positive trends continue. But they also show there's still work to do.

Urban school districts may have shown slightly more improvement than the nation as a whole, where results were largely stagnant.

The three Florida districts included in the Trial Urban District Assessment results provided their share of bright spots. In fourth-grade math, for example, Miami-Dade and Duval were two of just four districts that posted statistically significant score increases.

In both places, disadvantaged students helped drive increases.

Experts caution against using scores like the national assessment results released Tuesday to gauge things like the effects of specific policies or the performance of district leaders. However, the numbers paint a useful picture of how three Florida urban districts are doing.

Miami-Dade feels the love (more…)

This year's science results on the Nation's Report Card brought good news for Florida students, who posted some of the largest improvements in the country.

Their results on the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress' science exams improved compared to 2009. And they rose faster than the nation as a whole, which also improved.

Florida's scores among Hispanic students were among the best in the country, as were scores for low-income fourth graders.

Historically, Florida's performance on the national assessments has been mixed. Its students have performed increasingly well in reading, especially in fourth grade. They've tended to struggle more in math and science, especially in eighth grade.

In this year's science results, eighth graders matched the national average score for the first time.

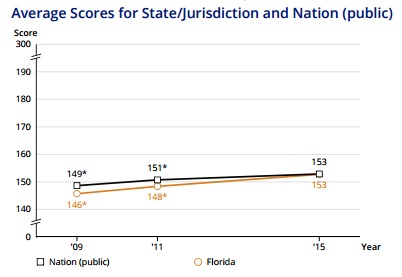

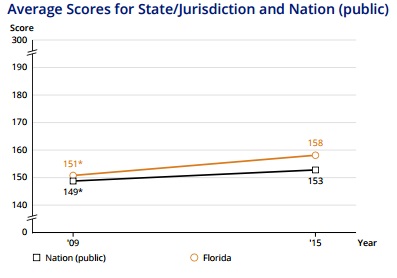

Florida's eighth-grade science scores caught up to the national average.

And fourth graders actually topped it, in a year when scores for the rest of the country also rose significantly.

Florida fourth graders' improvement outpaced the nation.

Overall, Florida's scores rose by an average of seven points in both grades over six years, compared to a national jump of four points. (more…)

Student achievement is more equitable, and improving more quickly, than the national average, but still trails the rest of the country in absolute terms. Source: Education Week, 2016 Quality Counts

It might have been a rocky year for education policy in Florida. But the latest rankings from Education Week show when it comes to student achievement, things remain fairly steady.

The 2016 “Quality Counts” report, released this morning, shows Florida continues to rank average to poor on many key academic indicators, but – with one notable exception – high in making progress and closing achievement gaps.

The 2016 “Quality Counts” report, released this morning, shows Florida continues to rank average to poor on many key academic indicators, but – with one notable exception – high in making progress and closing achievement gaps.

Overall, the state ranked No. 29 among 50 states (No. 30 with Washington D.C. in the mix), down from No. 28 last year. Gradewise, that’s a C-, compared to a C for the nation.

In K-12 achievement, Florida slipped from No. 7 to No. 11. It again posted a C. The nation again posted a C-. The top-ranked state, Massachusetts, earned the only B.

It wouldn’t be surprising if critics of Florida’s ed reform track point to the rankings as evidence of a slide, but so far the numbers don’t support the claim.

Between 2009 and 2013, Florida landed in or near the Top 10 every year in overall ranking. But after not giving grades in 2014, Education Week switched to a new matrix last year that cut the grading categories from six to three. The new formula nixed categories where Florida historically fared well, such as standards and accountability, and left two where it hasn’t: education spending and an EdWeek creation called the Chance-for-Success Index.

(For what it's worth, I find some of the sub-categories in the Chance-for-Success Index odd. Florida gets dinged, for example, because it has a lot of working-class folks who aren't college educated, or who don't speak English well. Yet evidence is strong that Florida's education system overcomes challenging demographics better than the vast majority of states.)

In the category that matters most, Florida has been on a roll.

Since 2009, it’s finished at No. 7, No. 7, No. 6, No. 12, No. 12, No. 7, No. 7 and now No. 11 in achievement. (more…)