Editor's note: Earlier this week, reimaginED unveiled a new report compiled by Denisha Merriweather, founder of Black Minds Matter and senior fellow at the American Federation for Children; Dava Cherry, former director for enterprise data and research at Step Up For Students; and Ron Matus, director for research and special projects at Step Up For Students. We are featuring it again today for anyone who missed it.

Editor's note: Earlier this week, reimaginED unveiled a new report compiled by Denisha Merriweather, founder of Black Minds Matter and senior fellow at the American Federation for Children; Dava Cherry, former director for enterprise data and research at Step Up For Students; and Ron Matus, director for research and special projects at Step Up For Students. We are featuring it again today for anyone who missed it.

Across America, education entrepreneurs are on the rise, fueled by frustration with traditional schools, a pandemic that magnified the inequities of public education, and the accelerating expansion of education choice.

Black education entrepreneurs are in the thick of it.

We wanted to learn more about this distinctive group of innovators. So, we surveyed Black school founders who are listed on the Black-owned Schools Directory maintained by Black Minds Matter. The responses we received from 61 founders are a first-ever glimpse into who these entrepreneurs are.

Here’s a taste of what they told us:

Who are the Black school founders?

Who are they serving?

What is motivating them?

What have they created?

You can read the full report here.

Imagine School at Broward is a tuition-free public charter school in Coral Springs, Florida, one of 712 charter schools in the state serving about 360,000 students. Imagine Schools is a national non-profit network of 51 schools in seven states and the District of Columbia.

Editor’s note: This analysis of a study conducted by the Center for Research on Educational Outcomes at Stanford University appeared Tuesday on edweek.org.

A new study shows that charter school students are now outpacing their peers in traditional public schools in math and reading achievement, cementing a long-term trend of positive charter school outcomes.

The study is the third in a series conducted by the Center for Research on Educational Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University, which has researched charter school performance since 2000. The third study, released June 6, is notable because it shows superior outcomes among charter school students while the center’s earlier studies showed charter school students performed either worse than or about the same as their peers in traditional public schools.

The researchers used standardized testing data from over 1.8 million students at 6,200 charter schools to determine how student learning at the schools compares to traditional public schools.

The most recent study covers student learning from 2014 to 2019. Its previous studies covered 2000-01 through 2007-08 and 2006-07 through 2010-11. CREDO’s study of that first period, released in 2009, found that charters failed to meet traditional public school outcomes.

The 2023 study reversed that narrative and showed that charters have drastically improved, producing better reading and math scores than traditional public schools. The results are “remarkable,” said Margaret “Macke” Raymond, founder and director of CREDO.

“The bigger lesson now in the post-COVID world is, hey guys if you’re looking for a way to improve outcomes for kids, here is an absolutely demonstrated framework that you can look at and maybe apply it in other contexts,” Raymond said.

Raymond said the improvement has come largely from existing schools tweaking their practices over time and getting better as a result—"evolution” rather than “revolution.”

To continue reading, click here.

Archdiocese of Miami Virtual School, owned and operated by the Archdiocese of Miami, offers full- and part-time enrollment, introducing students to Catholic virtues and principles while enhancing learning for participants across the country.

When Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed HB 1 into law, he praised it as “the largest expansion of education choice not only in this state but in the history of these United States.” During committee hearings, lawmakers called it “transformational.”

The sweeping legislation extended eligibility for the Sunshine State’s 20-year-old school choice program to every student regardless of income. It also gave parents more control over their children’s education by converting traditional scholarships to education savings accounts.

The accounts, called ESAs, allow funds to be spent on pre-approved uses such as curriculum, digital materials, and tutoring programs in addition to private school tuition and fees.

But despite the greater opportunities for customization, one thing was not included: religious virtual schools. Under the new law, students may use funds to attend non-sectarian virtual schools, such as Florida Virtual School, and traditional in-person religious schools, but not a combination of the two.

That language means that schools such as Archdiocese of Miami Virtual Catholic School and Families of Faith Christian Academy International, which offers a private virtual school option, are excluded from participating in the state’s K-12 education choice scholarship programs. However, families who are using personalized education plans under HB 1 are allowed to use ESA funds to buy curriculum from ADOM Virtual Catholic School, even though they can't use the money to enroll at the school.

The Lakeland-based school is working on passing inspections for a campus on property owned by Epic Church, according to its website. Students who attend the in-person campus full time will be able to use scholarships. Before the pandemic, the school offered a blend of traditional and home-based instruction for homeschool families.

However, when Covid-19 made online education more popular, the school focused more on its virtual offerings.

Jim Lawson, the administrator at Families of Faith, hopes that closing the loophole will be on the lawmakers’ list when the 2024 session begins.

“With all the good that is included in HB 1, which we support, the Florida Legislature has continued to limit a wide range of high-quality educational options,” said Lawson, administrator for Families of Faith, who co-founded the school in 1994 with several other homeschool families.

“Parents can choose a high-quality campus-based program that aligns with the academic needs of their students while not conflicting with their faith. But they are not given the same choice to choose a high-quality accredited virtual program for a faith-based private school. The foundational principle of school choice is to have the same menu of options that families who choose the public school system, which includes FLVS, available to them from the private sector.”

Jim Rigg, superintendent of schools for the Archdiocese of Miami, which has a virtual Catholic school that offers full- and part-time programs, has a similar perspective.

“We favor efforts that maximize the ability of families to choose the school that best fits their child’s needs,” Rigg said. “This would include faith-based virtual schools, such as the ADOM Virtual School used by hundreds of students throughout Florida and across the world.”

Some say the language puts HB 1 in conflict with the First Amendment’s free exercise clause cited in recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions Espinoza v. Montana and Carson v. Makin, which forbade Maine and other states from discriminating against religious schools in state education choice scholarship programs.

In Espinoza, the high court ruled that a state “need not subsidize private education” but that once it “decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

In Carson, the high court ruled that states could not ban faith-based schools from participating in state scholarship programs because the schools engage in religious activities. The case involved town tuition programs offered in some Northeastern states that offer students in rural areas funding to attend private schools where there are no district high schools.

“Likewise, a state need not subsidize families choosing virtual learning, but once it decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some virtual learning providers solely because they are religious,” Jason Bedrick, a research fellow at the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy, wrote in a recent analysis.

Shawn Peterson, president of Catholic Education Partners, a national organization that promotes greater access to Catholic education, agreed, saying that although he applauds the passage of HB 1 and welcomes the wealth of options it offers, he hopes to see some changes.

“We hope that lawmakers om the Sunshine State will fix the legislation to ensure that all providers to ensure that all providers can participate in the new program,” he said.

Bedrick urged lawmakers to tweak the bill by inserting language clarifying that notwithstanding any other provision in Florida statute, families using education savings accounts may choose virtual providers that offer religious or secular instruction, and that the language should specify that virtual learning counts toward regular attendance regardless of whether students are enrolled in brick-and-mortar schools.

“Florida has an opportunity to reclaim its mantle as the leading state for education freedom and choice,” Bedrick wrote. “With just a few small but important tweaks, the Sunshine State could adopt a policy on universal education choice that will be a shining example for other states to follow.

Any tweaks will have to wait until the 2024 legislative session, which begins Jan. 9.

Spring Valley School in Birmingham, Alabama, one of 457 private schools in the state serving more than 81,500 students, is a college preparatory school whose mission is to provide excellence in education for bright students with learning differences.

Editor’s note: This article appeared last week on al.com.

Alabama lawmakers passed tweaks to the state school choice landscape during the 2023 session but turned down proposals for sweeping expansions. Two school choice bills, one expanding the decade-old Alabama Accountability Act to allow school choice for students with disabilities, and one remaking the 8-year-old public charter school commission, received final passage Thursday.

The Alabama Accountability Act was expanded to allow more students to be eligible for tax credit scholarships, more money for individual scholarships, higher amount of tax credits available and more schools designated as priority – previously called “failing” – meaning more families could claim tax credits for moving their child away from a priority school.

The act now allows students with disabilities, specifically those with an Individualized Education Program or Plan called an IEP, to be eligible for tax credit scholarships to pay for tuition and fees. In addition, students with IEPs can use scholarship proceeds to pay for therapeutic services such as speech and occupational therapy.

More than 80,000 students statewide have IEPs. Currently, only students whose family income is below 185% of the federal poverty level are eligible. That level was raised to 250% under the changes.

About 2,800 students are using tax credit scholarships during the current school year according to the Alabama Department of Revenue. At its peak, more than 4,000 students used the scholarships.

Scholarship availability depends on how much money was contributed to the scholarship granting organizations that determine student eligibility and distribute scholarships. That figure, too, was increased to $40 million from the current level of $30 million.

Just under $20 million in contributions were claimed for tax credit purposes in 2021, according to the Department of Revenue.

To continue reading, click here.

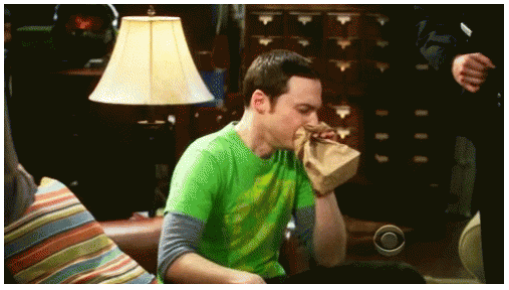

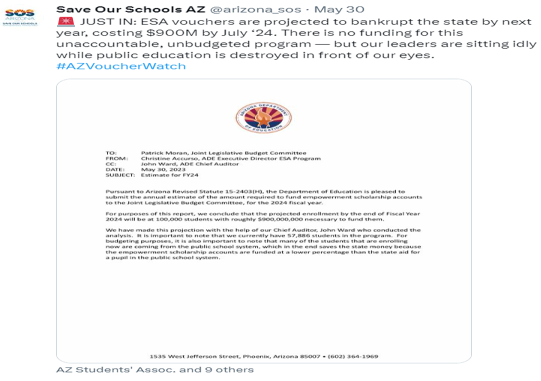

Last week saw some excitement in Arizona political circles as the Arizona Department of Education estimated 2024 Empowerment Scholarship Enrollment at 100,000 students. Sadly, “some excitement” translated into absurd fear mongering predictions of financial ruin for Arizona.

Last week saw some excitement in Arizona political circles as the Arizona Department of Education estimated 2024 Empowerment Scholarship Enrollment at 100,000 students. Sadly, “some excitement” translated into absurd fear mongering predictions of financial ruin for Arizona.

Allegedly, We.Are.All.GONNA.DIEEEEEEEE!!!!!!

If Arizona choice opponents had done a bit of math, they might have spared themselves from having to breathe into a paper bag. I can, however, be of some assistance: $900,000,000 divided by 100,000 students is an average of $9,000 per student.

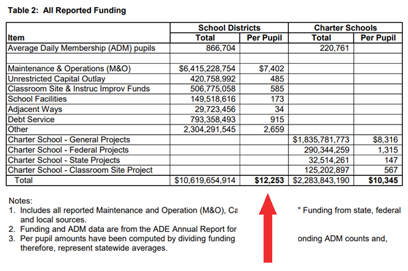

How much do taxpayers put per pupil into district and charter schools? Arizona’s Joint Legislative Budget Committee has an answer from fiscal year 2021:

JLBC also has a statewide estimate for fiscal year 2023 of an average of $13,306 per student. In the reverberations of the Arizona anti-choice echo chamber, you’ll hear people desperately trying to claim that it doesn’t matter that $13,306 > $9,000 because of different pots of money (local, state and federal) because reasons.

Reasons that cannot be coherently articulated, but reasons.

This belief is quite odd given that all the pots are filled up by the same taxpayers, who all pay local, state and federal taxes. Ergo, while the taxpayer may magnanimously pay more for students to attend district or charter schools at their option, it’s not like they have any reason to oppose children opting for the Empowerment Scholarship Account if that floats their particular boat.

This belief is quite odd given that all the pots are filled up by the same taxpayers, who all pay local, state and federal taxes. Ergo, while the taxpayer may magnanimously pay more for students to attend district or charter schools at their option, it’s not like they have any reason to oppose children opting for the Empowerment Scholarship Account if that floats their particular boat.

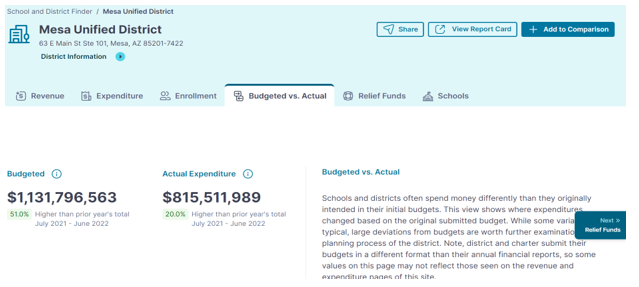

My Texas public school math training informs me that the average ESA students uses approximately 32% fewer taxpayer resources per pupil than the average Arizona student. For you incurable skeptics, consider the budget of Mesa Unified:

Mesa Unified had 54,000 students, was budgeted for $1.1 billion and change, actually spent $815 million and change. The memo that caused Arizona choice opponents to panic estimated 100,000 students at a cost of $900 million. So … ESA has far more students but fewer taxpayer dollars. If ESA is going to bankrupt Arizona, Mesa Unified is going to send Grand Canyon State taxpayers to a debtor’s prison.

Is the growth of the ESA program going to “destroy public education?” Hardly.

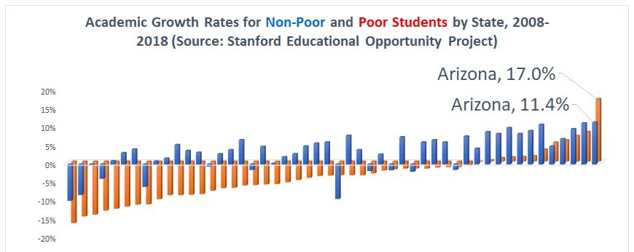

Arizona lawmakers have been listening to such non-stop predictions of doom since passing charter school and open-enrollment legislation in 1994. Since then, they have created a scholarship tax credit program (1997), expanded it multiple times, and created the Empowerment Scholarship Account program (2011) and expanded it multiple times. Lo and behold, Arizona’s spending per pupil in districts is currently at an all-time high, and this happened in academic growth:

Please, sir, can I have some more “destruction?”

Monica Hall, pictured here, opened T.H.R.I.V.E Christian Academy in Stone Mountain, Georgia, in 2013. T.H.R.I.V.E. stands for Truth, Humility, Respect, Integrity, Victory, and Excellence, the six pillars upon which the school was founded.

Editor’s note: This report was compiled by Denisha Merriweather, founder of Black Minds Matter and senior fellow at the American Federation for Children; Dava Cherry, former director for enterprise data and research at Step Up For Students; and Ron Matus, director for research and special projects at Step Up For Students.

Across America, education entrepreneurs are on the rise, fueled by frustration with traditional schools, a pandemic that magnified the inequities of public education, and the accelerating expansion of education choice.

Black education entrepreneurs are in the thick of it.

We wanted to learn more about this distinctive group of innovators. So, we surveyed Black school founders who are listed on the Black-owned Schools Directory maintained by Black Minds Matter. The responses we received from 61 founders are a first-ever glimpse into who these entrepreneurs are.

Here’s a taste of what they told us:

Who are the Black school founders?

Who are the Black school founders?

Who are they serving?

What is motivating them?

What have they created?

You can read the full report here.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Lindsey M. Burke, director, Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, and Jason Bedrick, research fellow at the center, appeared Wednesday on The Heritage Foundation’s website.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Lindsey M. Burke, director, Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, and Jason Bedrick, research fellow at the center, appeared Wednesday on The Heritage Foundation’s website.

In his essay “Opening Doors for School Choice,” Rick Hess has offered characteristically sage and sober advice to advocates of school choice. In the midst of the movement’s most successful year ever—five states have enacted universal education savings accounts or ESA-style policies so far, in addition to several more new or expanded choice policies—Hess urges advocates to leverage their momentum prudently.

The window of opportunity for school choice is still open, but who knows for how long? To take full advantage before the window closes, Hess advises advocates to focus on how school choice solves problems for parents; to pay attention to the details of how choice policies work for families and educators, from transportation to barriers to entry; to explain how choice policies better serve the public interest; and to ensure that choice policies serve all families, not just the worst off.

However, it is worth elaborating on a point Hess made in passing that holds the key to this recent progress. In explaining why parents embraced school-choice policies in the wake of the pandemic-era school closures, Hess observes:

Parents were left hungry for alternatives, especially amidst bitter disagreements over masking and woke ideology. This was all immensely practical. It wasn’t about moral imperatives or market abstractions. It was about empowering families to put their kids in schools that address their needs, reflect their values, and do their job.

The choice movement’s recent successes stem from a confluence of factors, but one key ingredient has been a shift in how some central players in the movement talk about school choice. In his seminal book, “Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies,” John Kingdon argued there are fleeting moments in which a public policy problem, favorable political conditions, and a ripe policy idea are in alignment.

School closures and the politicization of the classroom posed a significant public policy problem for many families to which school choice could provide a solution, both in offering parents an immediate escape hatch to educational alternatives and in giving parents more bargaining power with their local district schools. When school officials know that dissatisfied parents can take their money and leave, they have a strong incentive to listen.

However, leveraging the favorable political conditions required choice advocates to connect with parents over cultural issues—an approach that the movement had previously avoided.

To continue reading, click here.

David Facey, who attends a private school in Florida using a Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities, cheers for the Tampa Bay Lightning at a game in Tampa during the 2022-23 hockey season.

PINELLAS PARK – David Facey remembers sitting in his Language Arts class last year hoping for salvation. Hoping someone would pull the fire alarm. Drastic, yes, but anything to bring class to an end.

The other students were nearly finished with their writing assignment. David had written only three words.

His teacher noticed. She wasn’t happy.

“David, what’s wrong with you?” she asked. “You need to concentrate.”

David wanted to scream.

It’s not a lack of focus. It’s dysgraphia, a neurological disorder that affects his ability to write. David can’t write within the lines. He can’t properly space letters. It took him nearly the entire class to write those three words. His hand cramped. He had a headache. He could no longer remember what he was writing about.

The topic was the ocean. David can talk for hours about the ocean. He just can’t write about it. That led to a confrontation with the teacher, a trip to the principal’s office, and a phone call to David’s mom.

David’s biological mother used drugs throughout the pregnancy, said Betty Facey, who along with her husband, Arlen, adopted David when he was 3. David was born addicted to those drugs. As a result, he has dysgraphia and dyscalculia, another neurological disorders where he struggles with numbers and math. He has atypical cerebral palsy, which affects his core strength and fine motor skills. He struggles with anger management.

“His are more hidden disabilities,” Betty said.

David, 14, didn’t have a problem in school until the Faceys moved from Michigan to Pinellas Park in 2021. Betty learned the teachers at his assigned school were not following his individual education plan. He couldn’t understand assignments. He couldn’t complete them. He couldn’t keep up with his classmates.

And when confronted by his teachers, he couldn’t control his anger.

“I would act all crazy and stuff,” David said.

With the help of an education choice scholarship, Betty enrolled David at Learning Independence For Tomorrow (LiFT) Academy in Seminole. LiFT is a private K-12 school that serves neurodiverse students.

“I would say if Florida didn’t have this (education choice) option, he would be stuck in (his assigned school) school,” Betty said. “He’d have to put up with the stuff they were dishing out. … He would hate school. He would probably not have a chance to graduate.

“To me, to be able to get him in a place like LiFT, which really is the perfect place for him, is sort of like a miracle.”

To continue reading, click here.

Cornerstone Christian School outside Omaha, Nebraska, one of 228 private schools in the state serving more than 42,000 students, is a non-denominational Christian school that uses a biblical-based curriculum. Its mission is to equip children with “godly character and biblical truth.”

Editor's note: This commentary from Valeria Gurr, a Senior Fellow for the American Federation for Children and a reimaginED guest blogger, appeared Saturday on Nebraska's townhall.com.

Just a decade ago, there were only a couple dozen states in the U.S. with school choice programs. This week, Nebraska has made history as the 50th state in the nation to pass a school choice bill — a monumental win for families in the Cornhusker State.

This passage is not only a major victory for the school choice movement in Nebraska; it is also a testament to the advancement of educational freedom and opportunities nationwide for all children, regardless of color, race, or economic status.

Nebraska’s LB753, the Opportunity Scholarship Act, which just passed with a supermajority from the Unicameral Legislature, establishes a tax-credit scholarship that will help more than ten thousand students attend a non-public school of their choice.

Scholarships will average around $9,000 per student, depending on the needs of the family and tuition costs.

The Opportunity Scholarships Act will give first priority to students living in poverty, students with exceptional needs, those who experienced bullying, are in the foster system or are in military families, and children denied enrollment into another public school.

With the goal of empowering families, passing school choice in Nebraska was the right thing to do. As a Hispanic education advocate, I am fighting for my community to overcome inequality in education. A high-quality education is one of the only paths to success for children living in poverty.

A quality K-12 education is a path to economic progress and opportunity, preparing students for college and successful careers, and school choice will always be part of the solution since the traditional system of education will never fit all the individual needs of students and families.

To continue reading, click here.

East Texas Christian Academy in Tyler, Texas, is one of 2,037 private schools in the state serving more than 331,600 students. Founded in 1979, East Texas Christian provides a quality education in a loving, supportive environment with a dedicated faculty and staff who integrate the word of God in every subject.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jonathan Butcher, Will Skillman senior fellow in education at The Heritage Foundation and a reimaginED guest blogger, and Mike Gonzalez, the foundation’s Angeles T. Arredondo E Pluribus Unum senior fellow, appeared Friday on houstonchronicle.com.

Will additional private education choices force a mass exodus from assigned schools in these areas? Or everywhere across the state?

The answer to the first question is no. As best as we can determine, private learning options implemented in states including Arizona and Florida have never resulted in a public school shutting down.

A proposal to create education savings accounts offers parents and students more than just a new school. The accounts are not vouchers, and the distinctions are important. Arizona courts emphasized the differences in a 2013 opinion and ultimately ruled that the accounts did not violate the state constitution.

With vouchers, or private school scholarships, parents can choose a new school for their child — a life-changing option for children who have been bullied, are falling behind in class, or for whom the assigned school has not met their needs.

With an account, after parents choose not to send their child to a public school, the state deposits a portion of a child’s funding from the state education formula into a bank-style account. (Under Abbott’s proposal, that would be $8,000 per year.) The parents can use the money to buy certain preapproved education products and services for their children.

Private school tuition is one option for parents, but not the only one. Parents who want to offer their children a course not available at a local public school can use an account to pay for the course online or at a local college. Or they can find personal tutors or education therapists suited to meet a child’s unique needs.

The education options that Abbott seeks will not change local high schools’ role as key parts of civic life. By our calculations, just 5% of Arizona students use education savings accounts, and 2% of children in Florida participate.

To continue reading, click here.