U.S. students' test scores slumped on international reading, math and science assessments, with historically dismal results in math. But American students' declines on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) were smaller than those in most other countries, so our international rankings improved in all three subjects. The Biden Administration credited billions of dollars in additional pandemic-era education spending for stemming the losses.

Why it matters: One of the most valuable uses of international assessments is the chance to scrutinize American assumptions around teaching and learning.

Many disadvantaged students are not given access to rigorous math instruction, starting from a young age, said Shalinee Sharma, the chief executive of Zearn, a widely used math platform for elementary and middle school students.

Unlike some countries that embrace math as a learned skill, the United States tends to treat math as a talent — designating only certain students as “math kids,” she said. That philosophy can especially hurt low-income students.

“When they do get access to high-quality math learning,” she said, “they excel.”

Numbers to Know

65%: Share of students in OECD member countries (largely industrialized democracies) who report feeling distracted by digital devices during math lessons.

45%: Proportion of students who reported feeling nervous or anxious if their phone wasn't nearby.

7: Percentage point decline, from 2018 to 2022, in the proportion of American students who say they feel "like an outsider" at school.

$2,625: Estimated cost increase, per student, of fully implementing New York City's new class size caps in elementary schools.

$213.3 million: Amount of third-round pandemic relief funding North Carolina school districts spent on HVAC upgrades.

Key Findings

Chronic absenteeism is up across the board, but especially among rural and Latino students.

Participating in centralized enrollment in New Orleans' all-charter public school system made schools more accessible to nonwhite students and had little impact on their state accountability ratings.

Geographic preferences and sibling preferences for access to New Orleans charter schools disproportionately tend to favor white students.

A California "right to read" lawsuit prompted changes that improved reading instruction.

Oakland community members trained to work as literacy tutors were just as effective as teachers in boosting student reading results.

The Last Word

When we can’t or don’t talk freely, we lose the chance to find real common ground, acknowledge complexity or grasp that even our own opinions can be malleable. If we listen only to those who already agree with us, we won't make wider connections. We won't grow.

- Zach Gottlieb, Los Angeles high school senior, on the closing of the teenage mind and what to do about it.

James Arthur Baldwin was an American novelist, playwright, essayist, poet and activist. His essays, as collected in Notes of a Native Son (1955), explore intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western society, most notably in regard to the mid-20th century.

“You were born where you were born and faced the future you faced because you were black and for no other reason,” James Baldwin wrote to his nephew James in 1962.

“The limits to your ambition were thus expected to be settled. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity and in as many ways as possible that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence. You were expected to make peace with mediocrity. Wherever you have turned, James, in your short time on this earth you have been told where you could go and what you could do and how you could do it, where you could live and whom you could marry.”

Nearly 58 years have passed since Baldwin wrote those words. How much has changed?

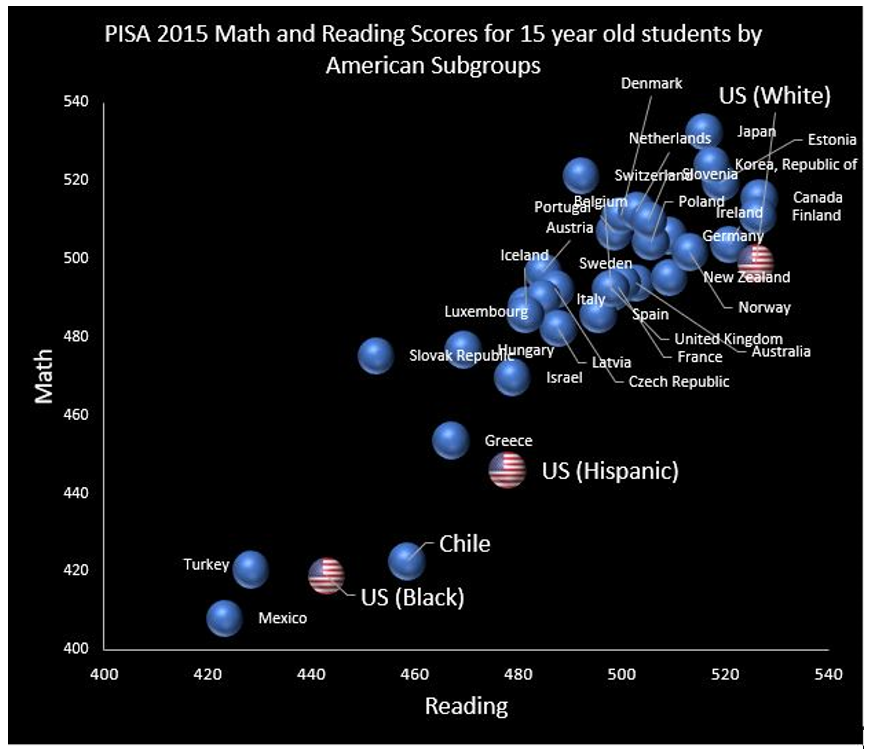

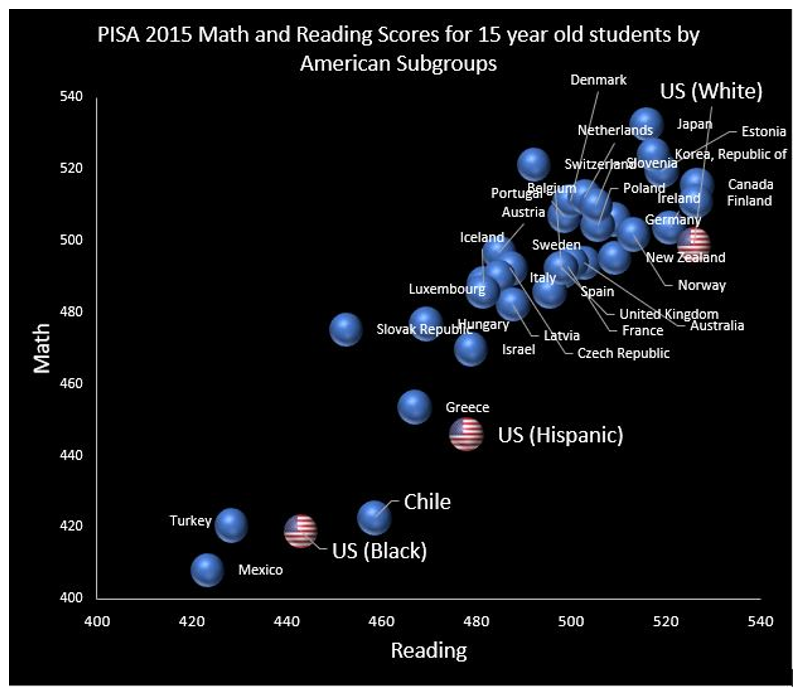

Are Black students still “not expected to aspire to excellence” and to “make peace with mediocrity?” Look at the PISA math and reading exam results and judge for yourself:

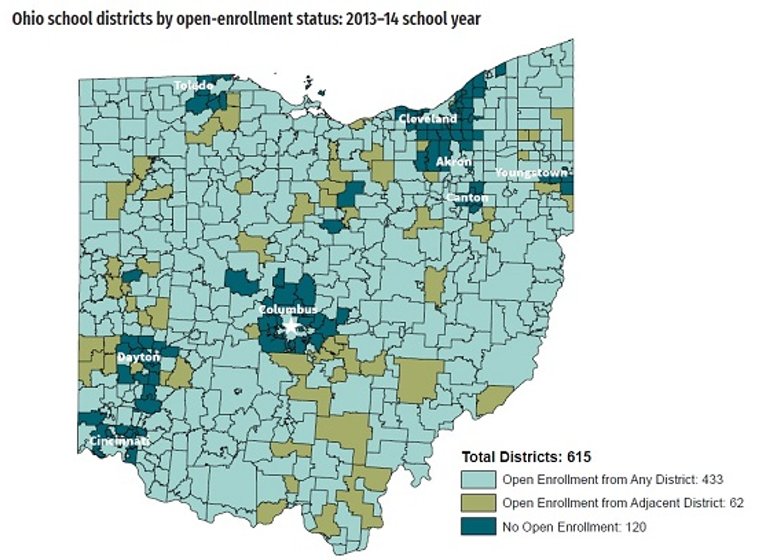

Are people still telling Black students “where you could go and what you could do?” Ask Kelly William-Bolar, a Black mom who spent time in jail for sending her children to a better-performing public school in Ohio. Read the Newsday investigation regarding the continuing role of race, income and real estate in segregating families by school.

Or look at the report published by the Fordham Institute on interdistrict open enrollment in Ohio, a first-of-its-kind analysis conducted by researchers at Ohio State University and the University of Oklahoma. See any suburban districts volunteering to take urban kids through open enrollment transfers?

Me neither, which leads inevitably to the conclusion that Kelly William-Bolar’s case was anything but a fluke, that those lines were working exactly as intended, and still do today.

Hundreds of thousands of students, many of them students of color, sit on private choice and charter waitlists. Anti-choice interests not only shamelessly do whatever they can to keep those families waiting, but they also sometimes mumble about segregation in a theoretical fashion, attempting to justify their actions. The gigantic and all-too-real sort of segregation on display in the map above does not ever seem to merit their attention.

“The purpose of education,” Baldwin wrote “…is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions.”

The time is long past for families to make their own decisions about where and how their children will be educated.

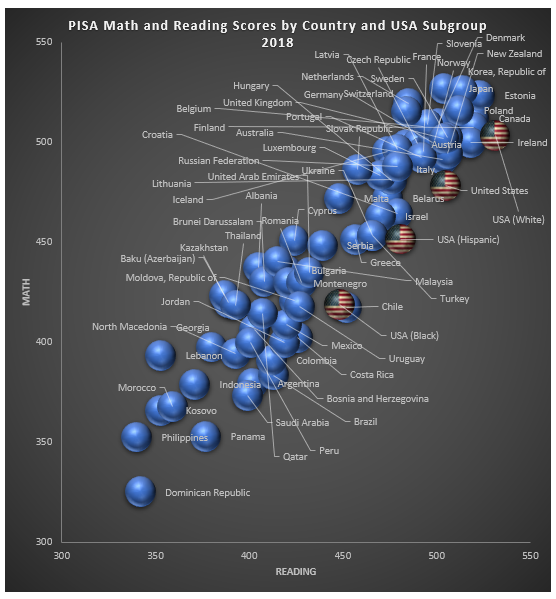

PISA, the OECD's Programme for International Student Assessment, measures 15-year-olds’ ability to use their reading, mathematics and science knowledge and skills to meet real-life challenges.

The performance of American 15-year-olds in reading and math has remained stagnant for the past two decades according to results released this past week from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Meanwhile, the achievement gap in reading between high- and low-performing students has grown wider.

The less-than-stellar results from the exam, the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), mirror recently released scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which I described in an earlier post as an Agincourt-level disaster.

The less-than-stellar results from the exam, the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), mirror recently released scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which I described in an earlier post as an Agincourt-level disaster.

Chile is the country most closely resembling the math and reading scores of American black students; Turkey most closely matches the combined achievement of American Hispanic students. Yet the United States spends more than twice as much per pupil as either Chile or Turkey.

Even the scores for American white students, while internationally competitive, appear less than impressive.

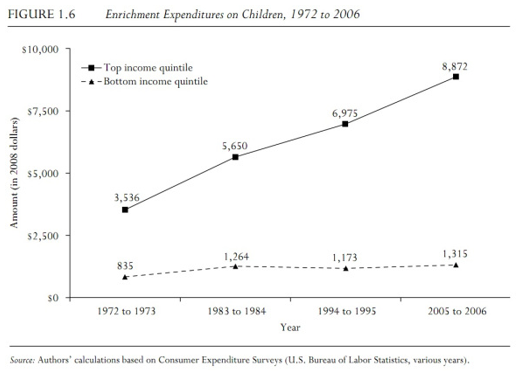

Estonia scores a bit higher while spending half as much per pupil as the United States. Moreover, scholars have made us aware that higher-income American families spend lavishly on enrichment options for their K-12 students (tutoring, club sports, etc.), and that this spending has increased steadily over time.

How many Estonian families do you reckon spend $8,872 per child per year on enrichment spending? Since the average American income is more than $26,000 per person higher than that in Estonia after adjusting for purchasing power, I’m going to walk out on a limb and dare a guess: Not many.

And, while enrichment spending apparently has little to do with improvement among low-income students (the trend in such spending is flat since the early 1980s), that isn’t the case among advantaged students. Richer in schools twice as well funded but underperforming is not a great place for America’s highest-performing subgroup to find itself vis-à-vis Estonia.

Even without these latest PISA results, but reinforced in light of them, it’s clear that without the benefit of lavish enrichment spending and other related advantages, the high levels of spending in American schools appears broadly ineffectual for students of color.

“Midway,” directed by Roland Emmerich, is based on real-life events in the clash between the American fleet and the Imperial Japanese Navy that marked a turning point in the Pacific Theater during WWII. While the Battle of Midway is a great reminder of American society’s admirable traits, the U.S. must continue to expand opportunity for everyone in the education arena to flourish in a growing and innovative society.

Trips to the cineplex are important holiday rituals in the Ladner clan, and Midway was on the viewing list this year. I enjoyed it. Looper issued a video with several scenes you might suspect were Hollywood embellishments. But nope, they actually happened.

The Battle of Midway is a helpful reminder about many admirable aspects of American society. George Orwell said that to understand London, one had to visit Paris. Imperial Japan is a good stand-in for our un-America, which allows us to understand ourselves better.

Japan of the 1930s was a monarchy run by rival elites of the Army and Navy. The film does a decent job of portraying this rivalry and hints at the precipitating cause of the Pearl Harbor attack. Japan imported most of its oil from the United States at the time. Horrified by atrocities in Japan’s empire building in China, the United States passed an embargo on the sale of oil to Japan. The Japanese elite decided to secure new sources for oil but understood the need to knock out the American fleet at Pearl Harbor to do so.

All of this reminds me of a quote from Matt Ridley’s book, “The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerge.”

The elite gets things wrong, says Douglas Carswell in “The End of Politics and the Birth of iDemocracy,” because they endlessly seek to govern by design in a world that is best organized spontaneously from below. Public policy failures stem from planners’ excessive faith in deliberate design. They constantly underrate the merits of spontaneous, organic arrangement, and fail to recognize that the best plan is often not to have one.

Elitist societies, like the pre-Civil War American South, are prone to making rash decisions to suit the needs of their elite. Japan’s elite got the Pearl Harbor attack very, very wrong, and it cost their country dearly. Japan had employed similar tactics successfully against Russia earlier in the century, but the United States was no sclerotic Czarist Russia.

Despite putting a priority on Europe, the USA was far more than Japan would ever have been able to handle. At one point, for instance, the United States was producing a new state-of-the-art aircraft carrier per month. Japan brought six such carriers to attack Pearl Harbor and lost four of them at Midway.

The pilots who carried out the Pearl Harbor attack were the best trained in the world. Their planes were superior to ours at the outset. The elitism of pilot training, however, represented a severe weakness. Many of the pilots who carried out the Pearl Harbor attack died in the battle of Midway. Given that pilot training was akin to graduating from Harvard Law in the Japanese system, this was a huge problem.

Where did the United States get enough pilots to crank out a new fleet carrier every month? It went something like “Hey Tommy, you’re a bright kid and good in a fight. How would you like to become a fighter pilot?”

American planes improved in quality and quantity. Admiral Yamamoto, the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack, realized the scale of their folly after the attack, stating, “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.”

The Japanese elite had not just underestimated American industrial capacity and human capital; they also underestimated American ingenuity. “Midway” accurately portrays the crucial role played by American codebreakers in the pivotal Midway battle.

Yamamoto aimed to draw the remaining American aircraft carriers into a trap by attacking Midway Island. Admiral Nimitz learned of their plans and instead had our remaining carriers lying in wait to destroy the four Japanese carriers. A group of Navy musicians proved crucial to the codebreaking effort.

A key to American success in World War II was making good use of talent, whether in the form of repurposed musicians or Rosie the Riveter back in the factories. We were much better at this than Imperial Japan, but not as good, either then or now, as we could or should be.

Today, state, national and international testing data show that talent development is not normally distributed in the United States. White students in America sit comfortably among the ranks of the top European and Asian education systems, while American black and Hispanic students score closer to the averages of countries that expend a fraction of our financial effort:

Our ancestors weren’t afraid of foreign competition. They made the foreign competition afraid of us. If we want to “make America great again,” we need to expand the opportunity for everyone to flourish in a growing and innovative society.

Equipping children with literacy and numeracy is a key component of mobility. The performance of our education system is a major impediment to such an aspiration, and in fact, may have us trending toward a detrimental elitism of our own.

Several weeks ago, we looked at American racial achievement gaps in math and reading from an international perspective using data from the Program for International Student Assessment, an international test that every three years measures reading, mathematics and science literacy of 15-year-olds.

In 2012, the PISA exam included subgroup specifically for Florida. Let’s take a look:

So, a couple of notes. This PISA data is from 2012. The National Center for Education Statistics shows that Florida’s white, black and Hispanic students all saw very large academic gains since the 1990s. We have reason to fear, therefore, that if the PISA exam had been given in, say, 1998, the results would have looked very frightening indeed. As it is, the results didn’t look so great in 2012.

Florida’s black students land in the vicinity of students in Chile and Mexico. Chile and Mexico spend only a fraction of what is spent per pupil in the United States and must contend with much larger student poverty challenges. Florida’s Hispanics scored higher, but still performed similar to students in Greece and Turkey, lower-spending countries.

The Third International Mathematics and Science Study exam from 2015 allows us to take a similar look at Florida subgroup achievement in international context. PISA and TIMSS test a different grouping of countries (with quite a bit of overlap) and test somewhat different things. Nevertheless, TIMSS also included Florida subgroups.

Here are the results for mathematics for nations and Florida racial/ethnic subgroups on eighth-grade math.

As was the case in the PISA data, American black students achieved similarly to students in nations that spend only a fraction of what American schools spend per pupil, and with more severe poverty challenges. Florida’s Hispanic students score higher but also find themselves outscored by countries such as Malta, Slovenia and Kazakhstan, which don’t begin to match American levels of spending. Florida’s Asian and Anglo students didn’t conquer the globe but had scores that were comfortably European if not Asian.

Make what you will of this information, but in my opinion, we have miles yet to go.

The latest international test results confirm what Florida education reformers have been saying for years: Despite arguably the biggest academic gains in the nation over the past 15 years, Florida students still lag too far behind.

Released Tuesday, the math, science and reading results on the 2012 Program for International Student Assessment tests, better known as PISA, show 15-year-olds in both Florida and the nation are middling, or worse, compared to their peers around the planet.

Released Tuesday, the math, science and reading results on the 2012 Program for International Student Assessment tests, better known as PISA, show 15-year-olds in both Florida and the nation are middling, or worse, compared to their peers around the planet.

Sixty-five countries and economies participated in the tests, which have been given every three years since 2000. Florida, Massachusetts and Connecticut were the only states whose scores were reported separately.

In math, the U.S. mean score of 481 fell below the mean of 494 for the 34 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. In science, the U.S. mean of 497 fell below the OECD mean of 501. In reading, the U.S. mean of 498 was just above the OECD mean of 496.

Florida students scored 467 in math, 485 in science and 492 in reading, far below Massachusetts (at 514, 527 and 527, respectively) and Connecticut (at 506, 521 and 521 respectively). It’s worth noting that Florida has a far higher percentage of low-income students, 56 percent, compared to 34.2 percent for Massachusetts and 34.5 percent for Connecticut.

The trend lines for the U.S. were flat in all three areas. It ranked an estimated No. 26 of the 34 OECD countries in math, an estimated No. 17 in reading and an estimated No. 21 in science.

The three states didn’t participate in prior PISA tests, so it’s unclear from those tests whether they are making gains relative to their peers in the U.S. and beyond. Other academic indicators, including NAEP scores, AP results and graduation rates, show Florida students are among the national leaders in progress.

But when it comes to proficiency, too many aren't there yet. (more…)