“I am equal and whole.”

A.C. Swinburne, Hertha

“There is but one law for all … the law of our Creator, the law of humanity, justice … equity …”

Edmund Burke, Impeachment of Warren Hastings

To my mind, it is sad that many admirable political writers seem to overlook the utility in this distinction, thereby turning the words into an occasion for media conflict instead of clarity of expression in our hope for the welfare of the human individual and the civic order.

The more conservative among them tend to regard “equality” as the only proper term for describing not only what is a crucial fact of human nature but also for the moral and political implications that follow from that reality.

The more “progressive” voices seem to see and embrace this distinction between fact and act, using “equity” as the civic entailment of the datum.

The moral and economic implications that these “progressives” then draw from this distinction are seldom my own, but their vocabulary seems the more lucid in describing the political issues at stake. I am envious of their corner on this weapon of ethical thought.

For a very long time in the last century, I tried my best to grasp a clear and distinct meaning for our revolutionary gospel of 1776 retrieved from the Middle Ages – the concept that “all men are created equal.” In 1999, happy after collaboration with my then student (ever since professor) Patrick Brennan, that hope became our book, “By Nature Equal: the Anatomy of a Western Insight” (Princeton, 1999).

There is, we said, a need for a convincing recognition and description of a factual equality of every ungifted, inexperienced, uneducated human being with the likes of Lincoln, Einstein and Mother Theresa.

No such message was evident in that recent burst of political literature (not yet defunct) that, for me, was a dangerous intellectual mess but which purported to speak for our human equality. I refer to that slice of the academy that sees equality as an attribute of the three races when taken separately as a whole. Seen thus as clusters, each population, we are told, had the same share of the dull and the brilliant.

What these gurus are plainly saying is that we classic and superior geniuses are to be found in similar proportions among Blacks, whites and Asians (thus the same proportion of dodos). And this was the equality of mankind.

It is my happy impression that view of equality as a declaration of one’s own superiority is in decline. By now, many of these savants may be entering that same stage of human deficiency that they have attached to their intellectual inferiors. It should be a comforting possibility to these now fading savants that some of us think them still “equal.”

In the end, of course, each human must be so in order to merit equitable treatment according to his or her distinctive individual needs, deserts and prospects. Here we encounter the ideal structure of human law viewed as the response to the universal entitlement to equity in treatment.

Each of us has peculiar circumstances and deserts, and the law is to be rationally ordered to sustain, reward or punish accordingly. Equality demands it; equality delivers it.

Brennan and I concluded that there is no factual equality among humans save in that one concept seen by the Founders as “created equal;” this is intelligible as the claim that we humans, however clever, are in our freedom and power either to seek or ignore the good, embody the same (equal) “right” and “power” to perfect ourselves in some ultimate way that is beyond our grasp in its entirety but ours to embrace in faith.

This very American conception of reality might best be kept distinct from, though necessary to, the concept of social and legal equity and rights. But is this even relevant to schooling and the curriculum? To me, it seems to be the first and fundamental question for the human mind—however one answers it.

And it is an inequity to deprive the equal human child of its challenge.

Democratic presidential nominee Bernie Sanders has called for a moratorium on federal funding for all charter schools and a ban on for-profit charters. Photo credit: Nick Solari/Wikimedia Commons

When Sen. Bernie Sanders, a Democratic candidate for president, recently revealed his education plan, most of the ensuing news coverage focused on his criticism of charter schools and his call for a moratorium on their expansion.

Cue the usual op-eds and pundits booing him, attacking socialism and railing against infringements on a “competitive free market.”

I’m here in Florida booing the usual pundits.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m a longtime Sanders supporter who was disappointed in his attacks on a movement bringing equity to public education.

He’s misguided and misinformed.

His opinion is baffling coming from someone who values “Medicare for All.” A single-payer system would allow patients to spend health care dollars on public or private hospitals and doctors of their own choosing.

He doesn’t see how funding for health care and education could be similar, allowing patients and students a level of freedom and equity of care they can’t get any other way.

Like I said, he’s misguided.

But I don’t blame him.

To those who want to roast Bernie Sanders: My Nana used to say, when you point a finger at someone, there are three more pointed right back at you.

Bernie Sanders is listening to one viewpoint regarding education choice because one viewpoint is all he can hear.

This isn’t his fault.

Those who support education choice don’t have a singular, strong, compelling voice. Most of the arguments for choice focus on conservative values. Free markets. Competition. Anti-union.

Not exactly a bipartisan point of view.

Choice supporters don’t have a central organization or rallying cry on a national scale, like the NEA or AFT, with a network in every state responding to attacks with a coordinated strategy.

We show up at rallies with coordinated shirts.

That’s all we’ve got.

No national organizing model.

No national mobilizing model.

Armies of parents and advocates scattered throughout the country with little or no direction.

Little or no united front.

What is our big picture goal?

Our opponents respond to strength. Our strength is in the sheer numbers of parents and teachers who understand that the current system fails children in need.

And yet we underutilize them at every turn.

We allow the teachers union, which does little to help actual teachers, to act as the compelling voice on this issue.

We allow President Trump and Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos to be the face of our movement, rather than the hundreds of thousands of families benefiting from choice.

We get together at annual summits and conferences and praise lawmakers -- mostly white, mostly conservative, mostly male -- and then wonder over expensive wine and cocktails why the left isn’t catching on.

We look the other way when Democrats and other liberal mouthpieces send their own children to private or elite schools, rather than shame them for denying low-income families that same privilege.

We’re too busy fighting amongst ourselves, allowing opponents to pit us against one another. Charter supporters opposing voucher supporters. Non-profits fighting for-profit management companies. Scholarship supporters railing against home or virtual schools.

We write mealy-mouthed editorials, all the while hoping that our opponents will like us if we ingratiate ourselves enough.

What does that really do?

It weakens support for and among all of us.

It tells parents, “You can choose, but only from this list of preferred options.”

It shouts, “We trust parents…to a point.”

Progressives like Bernie Sanders see themselves as rebels. The ones who support redefining everything from health care, drug laws, and college tuition costs to reforming prisons, campaign finance and gun control.

Yet only in education reform are the rebels and reformers deemed conservative.

Unreal.

And we continue to allow it.

We don’t cultivate leaders to run for office or give them proper political cover to take on the status quo.

We allow the message to be, “We don’t need two school systems,” when anyone with open eyes – and an open mind -- knows there are already two systems: one for those with means, and one for those without.

Opponents run with the nonsense that we “drain money from public schools.” We don’t raise our voices just as high to declare it’s cruel to allow the current system to thrive.

We aren’t bold.

We aren’t loud.

We aren’t compelling.

Blame Bernie all you want.

We’re the ones hiding meekly in the corner. In our absence the opposing arguments thrive.

If we fix that, Bernie – and all our misguided opponents – will finally understand the issue. And then figure out where they stand.

Editor’s note: This month, redefinED is revisiting the best examples of our Voucher Left series, which focuses on the center-left roots of school choice. Today’s post from December 2015 describes efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot.

This is the all-in-one version of our recent serial about efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot. It's part of our ongoing series on the center-left roots of choice.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation.

***

Cue “Staying Alive.”

Disco was king. Jimmy Carter was president. And across the bay from Berkeley, the punk band Dead Kennedys was blasting its first angry chords. But in 1978, Coons and Sugarman still hadn’t gotten the carbon-copy memo that the ‘60s were over.

The ballot initiative they detailed in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice,” wasn’t gradual change, organic growth, nibbling at the edges.

It was revolution. (more…)

The Netherlands decided nearly a century ago to end long-running religious strife over schools and let 1,000 flowers bloom. The Dutch system of universal school choice gives full government funding to public and private schools, including all manner of faith-based schools. (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

Editor’s note: This month, redefinED is revisiting the best examples of our Voucher Left series, which focuses on the center-left roots of school choice. Today’s post explores one of the world’s most robust systems of government-funded private school choice in a country known as a progressive’s paradise: the Netherlands.

By common definitions, the Netherlands is a very liberal place. Prostitution is legal. Euthanasia is legal. Gay marriage is legal; in fact, the Netherlands was the first country to make it so. Marijuana is not legal, technically, but from what I hear a lot of folks are red-eyed in Dutch coffee shops, saying puff-puff-pass without looking over their shoulders.

Given the rep, it might surprise school choice critics, who tend to consider themselves left of center, and who tend to view school choice as not, that the Netherlands has one of the most robust systems of government-funded private school choice on the planet. Next year the system will reach the century mark, with nearly 70 percent of Dutch students attending private schools (and usually faith-based schools) on the public dime.

By just about any measure, the Netherlands is a progressive’s paradise. According to the Social Progress Index, it was the ninth most progressive nation in 2015, down from No. 4 in 2014. (The U.S. was No. 16 both years.) On the SPI, it ranked No. 1 in tolerance for homosexuals, and No. 2 in press freedom. On another index, the Netherlands is No. 1 in gender equality. (The U.S. is No. 42.) It’s also among the world leaders in labor union membership (No. 19 in 2012, with 17.7 percent, eight spots ahead of the U.S.). And by some accounts, Amsterdam, the capital, is the most eco-friendly city in Europe.

Somehow, this country that makes Vermont look as red as Alabama is ok with full, equal government funding for public and private schools. It’s been that way been since a constitutional change in 1917. According to education researcher Charles Glenn, the Dutch education system includes government-funded schools that represent 17 different religious types, including Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu and Rosicrucian, and hundreds that align to alternative bents like Montessori and Waldorf.

Glenn, an occasional contributor to redefinED, has written the book on the subject. He calls the Netherlands system “distinctively pluralistic.”

The Netherlands' tradition of pluralism dates back hundreds of years. After the Dutch won their independence in 1609, Amsterdam became the commercial capital of Europe. It served as a hub for trade and finance, a cultural center that produced the likes of Rembrandt, and a refuge for migrants from across the continent, many of whom came fleeing religious persecution.

By the late nineteenth century, however, the country's diverse religious factions, including Catholics, different Protestant sects, and various secular groups had created their own cultural silos, or "pillars." Each had its own churches, its own schools, and its own social clubs. Some wanted public schools to be faith-based. Some wanted them to be “neutral.” Some wanted them to reflect one faith more than another.

The 1917 constitutional change was part of a broader reconciliation in Dutch politics called “The Pacification.” It followed decades of strife over schooling. No remedy worked until different factions agreed to let the parents decide, and let the money follow the child.

The system continues to have its tensions and tradeoffs. Some liberals still wonder if “common schools” would be better at unifying a country that grows ever more diverse. The influx of Muslim immigrants gives people pause, even as older divisions between religious factions fade. The Dutch way also includes far more regulation than some choice stalwarts in the U.S. would be comfortable with.

I don’t know enough to have a good opinion. But Glenn does, and he concludes most parents and the general public in the Netherlands are satisfied with their schools. Ed policy expert Mike McShane also points out the Dutch system produces some of the world’s best academic outcomes (Top 10 internationally in math, science and reading), at less cost per-pupil than the U.S. That should count for something.

For my skeptical liberal friends, I’d like to note that even the socialists are on board. Even before the 1917 constitutional change, the Socialist Party in the Netherlands was backing full public funding for private and faith-based schools. Why? Because, according to a resolution it adopted in 1902:

“Social democracy must not interfere with the unity of the working class against believing and nonbelieving capitalists in the social sphere for the sake of theological differences … “

There you have it: Fight the man. Not school choice.

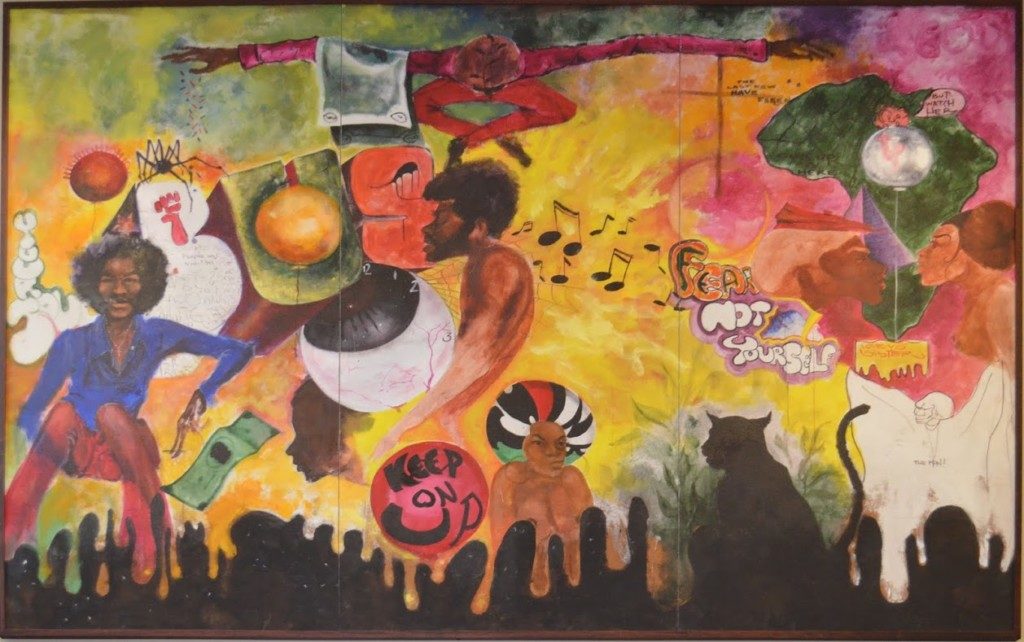

One of a series of murals covering the walls of the Center for Pan-African Culture at Kent State University, dedicated to a group of Kent State students called Black United Students, who first proposed the adoption of Black History Month

Editor’s note: This February marks the 43rd anniversary of Black History Month. redefinED is taking this opportunity to revisit some pieces from our archives appropriate for this annual celebration. The article below originally appeared in redefinED in December 2015.

Credit James Forman Jr. with the best account yet of the center-left roots of the school choice movement. Credit his stint as a public defender for being the spark.

Forman, now a Yale law professor, said the district “alternative” schools serving his juvenile clients in Washington D.C. 20 years ago were giving them the least and worst when they needed the most and best. He began exploring options like charter schools, only to be told by some folks that school choice couldn’t be trusted because of its segregationist past.

Forman, now a Yale law professor, said the district “alternative” schools serving his juvenile clients in Washington D.C. 20 years ago were giving them the least and worst when they needed the most and best. He began exploring options like charter schools, only to be told by some folks that school choice couldn’t be trusted because of its segregationist past.

Forman knew about the “segregation academies” some white communities formed to evade Brown v. Board of Education. But he knew that wasn’t the whole story. Among other reasons, he was the son of James Forman, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the group whose courageous members became known as the “shock troops” of the civil rights movement.

Wait, he thought, recalling stories his parents told him about Mississippi Freedom Schools. Wasn’t that school choice?

“It seemed impossible to me to think that over all of those years, African-Americans had never organized themselves to try to create better (educational) opportunities outside what the state was providing them,” Forman told redefinED in the podcast interview below. “So that was my idea. My thesis was there had to be an alternative history, there had to be a history of African Americans who were not relying on the government and were trying to organize themselves to create schools to educate their children.”

The result of Forman’s research is “The Secret History of School Choice: How Progressives Got There First.”

The 2005 paper traces the progressive movement for educational freedom from Reconstruction, to the civil rights movement, to the “free schools” and “community control” movements of the 1960s and ‘70s. A century before many activists were using the term “school choice,” it notes, black churches were making it happen. Decades before conservative Gov. Jeb Bush was pushing America’s first statewide voucher program, liberal intellectuals were promoting the notion in The New York Times Magazine.

A decade later, “The Secret History of School Choice” remains a must-read for anyone who wants a fuller, richer picture of choice’s beginnings. But Forman, who co-founded a charter school named for Maya Angelou, hopes progressives in particular see the light.

They ignore the history of school choice, and their role in shaping it, at their own peril, he said. Believing, wrongly, that it’s right-wing can result in it becoming just that. If progressives aren’t at the table, he suggested, they can’t bring their values to bear in shaping policy. In his view, it’d be good if they did.

Forman, for example, believes per-pupil amounts for many voucher and tax credit scholarship programs are too low for the low-income students they’re intended to help, reflecting conservative positions that education funding as a whole is bloated. (Other left-leaning choice supporters have raised concerns that modern voucher programs are too cheap.) Equity concerns surface in other ways, with few publicly supported, private school choice programs employing the sliding scales for family income and scholarship value that liberal voucher supporters in the ‘60s and ‘70s thought crucial.

“Our understanding of the history influences the direction that the issue goes,” Forman said. “If people who have an equality orientation and a civil rights orientation see themselves as on the outside of the movement for school choice, then the only people who are going to be left are people who have different motivations. … So the question is going to be, who owns the movement? Who directs the movement? Who is dominant? Whose educational vision leads the way?”

Forman said perceptions about choice will change as more and more low-income and minority parents embrace it. But the narrative won’t tack back to fully mesh with the reality of the movement’s diverse roots, he said, unless other things change too. One obvious hurdle, he said, is how the movement’s leadership ranks are “almost lily white.”

“Every time I go to a (school choice) conference, I am appalled by how invisible almost the folks of color can be at the top level of leadership,” Forman said. “That’s a problem.”

School choice programs are routinely demonized as nameless, faceless programs. Catherine Durkin Robinson of Florida Parent Network says it's past time to #SayTheirName

As an activist, voter and resident who leans way to the left, I read the news daily and find myself asking, out loud and with more than a bit of frustration:

“Can I get a left-leaning candidate for governor who knows something about educational choice in Florida?”

Is that too much to ask?

I run the Florida Parent Network – a dedicated team of organizers who travel this state listening to thousands of parents about why they choose something other than district-run schools. We listen … to hopes and dreams, triumphs and tragedies.

We see our parents’ love for their children shining through in every choice they’ve ever made.

We help them protect and defend those choices.

I am officially inviting candidates running for governor in this year’s Democratic primary to step outside their neighborhoods, circles and worlds of privilege and meet some of our parents too.

Maybe they’d learn something. (more…)

Catherine Robinson (second from left): "The next time my colleagues on the left yell and scream about Republicans turning on their values to support President Trump, I would like them to look in the mirror. You, too, are turning on your values to support a union and a system that limits opportunities for the people you claim to care about the most."

I’ve been a militant advocate, organizer and member of the Democratic Party for 30 years. A few months ago, I quit identifying as a Democrat.

It had been building within me for a while. I could no longer stomach the Democratic Party’s support for an education system that hurts so many poor and working-class families.

Democratic Party politicians have repeated their lies about educational options so long, they’ve begun to believe those lies. And they do this while so many of them can afford to move into desirable neighborhoods with good schools, or send their children to private schools.

I wonder how they sleep at night.

As far back as I can remember, I’d been raised to firmly identify and side with the poor and working class. My relatives were teamsters, union members and union organizers, Irish immigrants who fought for everything they got.

In college, I officially began my activism career by joining Students Against Apartheid. That led to gigs with Amnesty International, Greenpeace, Jerry Brown for President, Tampa AIDS Network, Florida Public Interest Research Group, and Sierra Club.

I worked as a counselor where I helped women choosing to end their pregnancies, sometimes holding their hands as they endured the most difficult moment of their lives. I marched on Washington and appeared on local talk shows, insisting that women had a right to control their reproductive lives.

I was almost arrested three times: protesting nuclear power, demanding an end to the war in Kuwait and demonstrating against animal cruelty.

For my 21st birthday, more than anything, I wanted an FBI file.

After college, I taught at alternative high schools and helped mostly young men, who had been expelled or arrested, turn their lives around. I also taught in district schools for students with special needs. All the while, I organized and advocated to repeal the Second Amendment, ensure marriage equality for all, protest armed conflict, provide for universal health care, expand voting rights, oppose private prisons and put out of business all circuses, rodeos and Sea World.

Six years ago, I met Michelle Rhee. I took a job with her national non-profit, organizing parents in several states to lobby for laws that put children’s needs ahead of adults’. Much to my surprise, Democratic friends and colleagues didn’t support this career move. (more…)

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

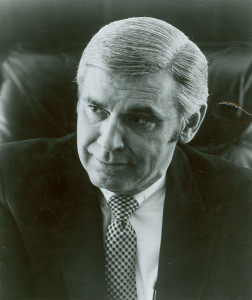

U.S. Congressman Leo Ryan was a popular Democrat who favored school choice. In 1978, he started working with Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman on a plan to put school choice on the statewide ballot in California. An early poll showed 59 percent of voters were in support.

All of us know Lincoln was assassinated. But not many know the twist of fate that left historians asking: What if? Had it not been for a clown of a cop named John Frederick Parker – who was supposed to be protecting the president at Ford’s Theatre, but instead slipped next door to the Star Saloon – America after the Civil War may have coursed in dramatically different directions.

The history of school choice has its own forgotten twist of fate.

It involves Berkeley law professors, a murderous cult, and U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan, a school choice Democrat. Given relentless attempts by choice critics and the press, in this age of Trump and hyper-tribalism, to portray choice as right-wing madness, it’s worth revisiting Ryan and what happened 40 years ago. Would white progressives still view choice as a Red Tribe plot had white progressives been the first to plant the flag? And in big, blue California to boot?

In 1978, Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Steve Sugarman laid out a social justice case for school choice in “Education by Choice,” a book that also offered a detailed policy blueprint. The prevailing system of assigning students to schools by zip code, they argued, was elitist and dehumanizing to low-income families. Their sweeping alternative included private school vouchers and independent public schools (which we now call charter schools). It also included visions of a system that would allow parents to build their kid’s educational programs a la carte, like today’s education savings accounts.

In 1978, Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Steve Sugarman laid out a social justice case for school choice in “Education by Choice,” a book that also offered a detailed policy blueprint. The prevailing system of assigning students to schools by zip code, they argued, was elitist and dehumanizing to low-income families. Their sweeping alternative included private school vouchers and independent public schools (which we now call charter schools). It also included visions of a system that would allow parents to build their kid’s educational programs a la carte, like today’s education savings accounts.

Coons and Sugarman wanted to plant seeds, not spark an instant revolution.

But then, serendipity.

Congressman Ryan, enjoying his third term representing the San Francisco Bay area, was a former public-school teacher and a product of Catholic schools. “Education by Choice” moved him. As fate would have it, his cousin went to church with Coons. So he had her invite Coons to dinner.

Ultimately, the professor and the congressman decided they’d try to get the California Initiative for Family Choice on the statewide ballot. All they needed was enough signatures. Ryan agreed to be the face of the campaign.

Choice couldn’t have found a better spokesman. Before Ryan was elected to Congress, he was a state lawmaker who practiced what one newspaper called “investigative politics,” and his aide Jackie Speier – now U.S. Rep. Jackie Speier – called "experiential legislating."

Ryan worked as a substitute teacher to immerse himself in high-poverty schools. He went undercover to experience Death Row at Folsom Prison. As a Congressman, Ryan trekked to Newfoundland to investigate the slaughter of baby seals, and even laid down on the ice to save a seal pup from a hunter.

It’s not a stretch to think Ryan’s popularity would have rubbed off on the ballot initiative.

The students at Mangrove School routinely visit nature parks and beaches. More than half the students beyond preschool use school choice scholarships.

This is the latest in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

SARASOTA, Fla. — At a nature park bedecked by oaks and palms, a teacher at Mangrove School mimics a wolf call through cupped hands, signaling to scattered students that it’s time to breeze over. “Let’s greet the day,” the teacher says. They all join hands, then take turns facing east, south, west, and north as their teacher offers thanks. To the rising sun. The palms and coonti. The manatees and crabs. Even to the soil.

So class begins at another choice school that defies stereotypes – and conjures possibilities.

On the one hand, Mangrove School is just another one of 2,000 private schools that accept Florida school choice scholarships. On the other, its mission to “honor childhood,” “promote world peace” and “instill reverence for humanity, animal life, and the Earth” is impossible to square with a pernicious myth – on the policy landscape, the equivalent of an invasive species – that school choice is being rammed into place by forces that progressives find nefarious.

“I hear that, and I look around here, and I think it’s very strange,” said Mangrove School director Erin Melia, a former chemist with a master’s degree in education. “I would think it (the perception) would be the opposite. The people most in need of choice are the people left behind.”

Mangrove School started as a play group 18 years ago. Now it has 43 students from Kindergarten to sixth grade, including eight home-schoolers who attend part-time. Nineteen of 35 full-timers use some type of school choice scholarship, most of them the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for lower-income students.*

“We’re just trying to be available to as many families as possible,” Melia said.

That’s a standard view among private schools participating in Florida choice programs, including plenty of “alternative” schools. (Like this one, this one, this one and this one). Those private schools serve more than 100,000 tax credit scholarship students alone. Their average family incomes barely edge the poverty line, and three in four are children of color. Yet the narrative about conservative cabals feels as entrenched as ever.

Blame Trump and the media.

Last March, six weeks after he was inaugurated, the most polarizing man on the planet visited an Orlando Catholic school and held up Florida school choice scholarships as a national model. Just like that, they became a bullseye. In subsequent months, The Washington Post, The New York Times, NPR, Scripps, ProPublica, Education Week and Huffington Post all took aim. Every one of them prominently mentioned the connection to Trump and/or Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. Ditto for the Orlando Sentinel, which punctuated the year with a hyperbolic series that attempted to portray the accountability regimen for private schools as broken.

Not a single one of those stories offered a nod to the fuller, richer history behind school choice. Or to its deep roots on the left. Or to the diverse coalition that continues to support it. So, again, a reminder: (more…)

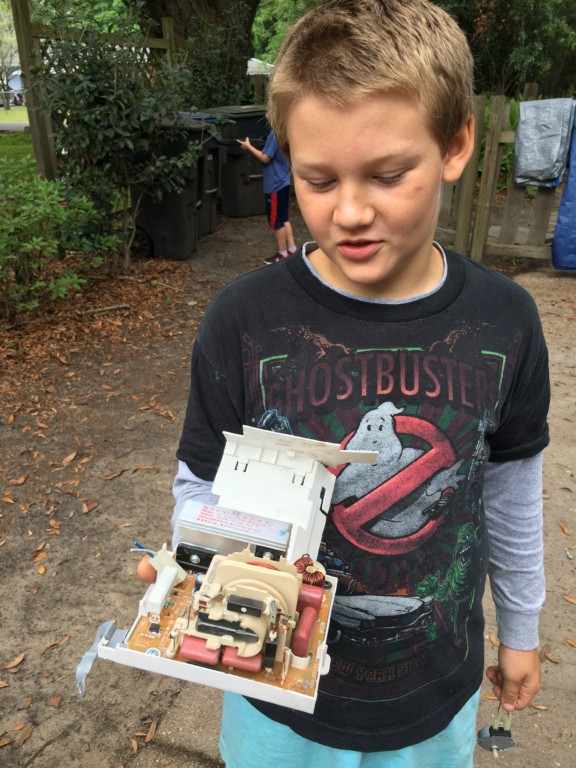

Cyrus Grenat, 10, had fun liberating this component from some gizmo during his "Taking Things Apart" class at the Magnolia School in Tallahassee, Fla. Cyrus attends thanks to a school choice scholarship.

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

With a few deft twists of a screwdriver, Cyrus Grenat, 10, detached one gizmo from an old microwave and another from a vacuum cleaner. At The Magnolia School in Tallahassee, Fla., this is school work.

Cyrus isn’t tested or graded in “Taking Things Apart,” an elective of sorts where out-of-commission radios, smart phones and other gadgets are sacrificed to curiosity.

His tiny private school doesn't do those things. It doesn’t assign much homework either. But once Cyrus gets home, the kid with the gears-turning grin and Ghostbusters T-shirt is planning to blow torch the copper out of one of his liberated components, and see if the other can be retrofitted for use in a remote-controlled car.

“It’s just fun,” Cyrus said. “I learn what’s in stuff, and how stuff works.”

With school choice in the national spotlight like never before, kids like Cyrus and schools like Magnolia could offer a lesson in how vouchers, tax credit scholarships and education savings accounts work.

And who benefits.

The K-8 school in a leafy, working-class neighborhood resists political labels. (I wish we all did.) But every year, its 60 or so students “adopt” a family affected by HIV. Its middle schoolers participate in a camping trip called EarthSkills Rendezvous. Nobody has issues with which bathroom the transgender student uses, or the school’s enthusiastic participation in National Screen-Free Week.

“We are definitely different,” said director Nicole McDermott, in an office barely bigger than Harry Potter’s bedroom under the stairs. “There are kids on the playground right now who are neurotypical, playing with kids who have autism, with kids who have social issues, with kids who have all kinds of differences. We are inclusive and diverse.”

School choice makes it even more so. The Magnolia School participates in three private school choice programs – the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for low-income students, the McKay Scholarship for students with disabilities, and the Gardiner Scholarship, an education savings account for students with special needs such as autism and Down syndrome.* About half the students at Magnolia use them.

That has made the school and its approach accessible to a wider array of families, said Susan Smith, the school’s founder. They, in turn, have enriched the school.

“This gives us the opportunity to reach further outside our little walls, so that our community reflects more of the community our children are going to grow up in, and work in, and make their families with,” said Smith, who has master’s degrees in humanities and elementary education. “It’s part of learning. Not just who you meet, and know, but who you solve problems with, and grow up with.”

The dominant narrative about choice would have America believe it’s a boon for profiteers, a crusade for the religious right, an ideological assault on a fundamental pillar of democracy. But if critics, particularly on the left, took a closer look, they’d see a more lively story – and one that has always included progressive protagonists. “Alternative schools” like Magnolia are among them, and there’s no reason why, with expanded choice, an endless variety of related strains couldn’t bloom. (more…)