This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, the American left cheered Freedom Schools and free schools, condemned education bureaucracies, and raised a clenched fist for community control of public education. It didn’t hesitate to think big on school choice, either.

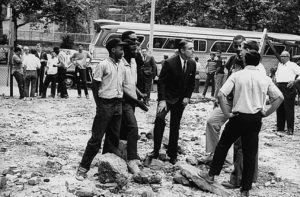

A few decades ago, some on the American left viewed school choice as a potential tool for expanding opportunity and promoting equity. An all-star academic team led by Harvard sociologist Christopher Jencks pitched one such proposal with funding from the Office of Economic Opportunity, which was formed to fight President Johnson’s War on Poverty and led by Sargent Shriver (pictured at center, above). Image from sargentshriver.org

Adjusting for inflation, Ted Sizer’s 1968 proposal for a $15 billion federal voucher program for low-income kids would ring up $105 billion today – making President Trump’s still-fuzzy $20 billion idea pale in comparison. A decade later, Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman fell short in their bid to bring universal school choice to California, but their gutsy campaign still punctuates a historical truth: school choice in America has deep, rich roots on the left.

Some of today’s progressives are enraged about the suddenly serious possibility of school choice from coast to coast. True, Trump’s touch makes progressive support unlikely. True, many conservative and libertarian choice supporters raise their own, more thoughtful concerns. But it’s still stunning to see how much progressive views on school choice have shifted over the course of a few decades.

For skeptical but curious progressives, this 1970 proposal for school vouchers is a worthy read. It was produced by an all-star academic team led by liberal Harvard sociologist Christopher Jencks, and funded by the federal Office of Economic Opportunity. That was the office, the brainchild of Great Society architect Sargent Shriver, that helped lead the charge in America’s War on Poverty.

Back then, vouchers weren’t maligned as a conspiracy to privatize public schools. Proponents, especially on the left, viewed them as a way to expand opportunity, promote equity, honor diversity, empower parents and teachers – and yes, improve academic outcomes.

The 348-page plan from the Jencks team is written in the language of social justice: Why, it asks, do we continue to call some colleges “public” when many people can’t afford them? Why do we call exclusive high schools “public” when only a few students can access them? Why are affluent parents considered competent enough to exercise school choice while low-income parents are denied?

The report brims with views like this: “ … [I]f the upheavals of the 1960s have taught us anything, it should be that merely increasing the Gross National Product, the absolute level of government spending, and the mean level of educational attainment will not solve our basic economic, social, and political problems. These problems do not arise because the nation as a whole is poor or ignorant. They arise because the benefits of wealth, power, and knowledge have been unequally distributed and because many Americans believe that these inequalities are unjust. A program which seeks to improve education must therefore focus on inequality, attempting to close the gap between the disadvantaged and the advantaged.”

The authors sorted through a wide array of potential variations on voucher design, and proposed a multi-year “voucher experiment” that would eventually be tried, sort of, in Alum Rock, Calif. Ultimately, the experiment proved a big disappointment; no district agreed to a plan that included private schools. Still, the report suggests the authors wanted a blueprint that could guide many communities, perhaps as part of a federal initiative. (more…)

Private schools have always been essential to black progress in America. As the author of a recent piece in The Atlantic wrote about Betsy DeVos and the African-American roots of school choice, "Private means to create a public good were an integral part of black education.”

Long before anybody used the term “school choice,” black communities were striving for it, often by any means necessary. Which is why black parents, though overwhelmingly Democratic by party registration, are likely to find their views on educational options to be more in line with Betsy Devos, the Republican nominee for U.S. Education Secretary, than the white progressives trying to derail her. Crazy times.

I’m not black, and I’m not a historian. But I don’t think there’s any doubt that fighting for educational freedom has been at the heart of the black experience in America. And yet, somehow, that epic struggle is overlooked in these polarizing fights over school choice – which is a shame, given the possibility it might make the fights less polarizing.

If I were king, I’d make white progressives read Yale Professor James Forman and listen to choice advocate Howard Fuller. In the meantime, if their tribal impulses are getting revved up over Betsy DeVos – and I know from my facebook feed they are 🙂 -- I’ll have the audacity to hope they check out this recent piece in The Atlantic, “The African American Roots of Betsy DeVos’s Education Platform.”

The author, College of Charleston Professor Jon N. Hale, offers a brief, nuanced look at choice through the lens of black history. That history isn’t always flattering to the choice “side.” Segregation academies, for example, did happen in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education. (Choice supporters have acknowledged that past, and noted how it differs from the ideals that spur today’s choice movement.) But that stain is a small part of a bigger story, in which private schools have been essential to black progress.

Writes Hale:

American history clearly demonstrates that communities of color have been forced to rely upon themselves to provide an education to as many students as possible. Students of color have rarely been provided a quality public education. As James Anderson demonstrated in Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935, black communities consistently had to provide their own schools by taxing themselves beyond what the law required, as white officials never appropriated public money equitably by race. Black civic leaders and educators had to forge alliances with philanthropists and “progressive” whites for further financial support.

Barred from the American social order, black educators, in effect, were forced to rely upon private means to meet the educational needs of their own children. African Americans established schools controlled by the community. Such “community-controlled schools” were by necessity administered by African Americans, taught by African Americans, and attended by African Americans.

Hale sums it up this way: “Private means to create a public good were an integral part of black education.”

The Atlantic piece mentions a few examples. We’ve explored others, including some that show how central faith was to many of these efforts. (more…)

Progressives hostile to school choice groan when they hear conservatives talking about school choice as a civil right. Some choice supporters get a little uncomfortable too.

But there are plenty of folks with bona fide civil rights credentials (see here, here, here and here for starters) who use the same language, because they genuinely view the parental choice movement as another phase of the civil rights struggle.

Martin Luther King III talked about school choice in the language of progressives and civil rights supporters: freedom, justice, opportunity.

Martin Luther King III is one of them. A year ago this week, he headlined a rally in Tallahassee that drew 10,000 people in opposition to the ongoing lawsuit against the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, the largest private school choice program in America.* The event spawned a ton of news coverage, and one of King’s quotes made the rounds: “If the courts have to decide, the courts will be on the side of justice,” he told the crowd. “Because this is about justice. This is about righteousness. This is about truth. This is about freedom. The freedom to choose what’s best for your family, and your child most importantly.”

The whole of King’s remarks didn’t get as much attention. (See them in the video above, starting around the 5-minute mark.) So what better time than now, the holiday commemorating his father’s birthday, to give it a spotlight?

MLK III describes himself as a human rights activist. He is pro-Obama, pro-labor, pro-environment, pro-gun control. And his speech touched on reasons for school choice that choice-friendly progressives have long emphasized, particularly opportunity and diversity. King wove in comments on other issues that day – poverty, defense spending, criminal justice – that left no doubt he’s a man of the left. I suspect the massive crowd before him that day, overwhelmingly black and Hispanic, largely shared his views.

Despite popular perception, both left and right have supported school choice, and both have advanced compelling arguments in favor. Unfortunately, the views of the pro-choice left have been obscured by a bogus narrative that vouchers, charter schools and related programs are part of a sinister, right-wing scheme to destroy public schools.

Thankfully, somebody forgot to tell MLK III – and the thousands of parents cheering him. Here's what he said as his speech came to a close:

My dad told us a lot of things. He used to say that the ultimate measure of the human being is not where one stands in times of comfort and convenience. But where one stands in times of challenge and controversy.

He went on to say that on some questions, cowardice asks: Is the position safe? He said expediency asks: Is the position politic? He said vanity asks: Is the position popular? But that something deep inside called conscience asks: Is the position right?

He went on to say that sometimes we must stand up for positions that are neither safe nor popular nor politic. But we must stand up because our consciences tell us they’re right.

That’s what we are here for today. Because we’re standing on the right side of what’s right for our children ...

I hope more progressives give MLK III a listen.

Because on school choice, he’s right. From the left.

*The Florida Tax Credit Scholarship is administered by nonprofits such as Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog and pays my salary.

Twenty-six of 62 students at Heart Pine School use tax credit scholarships. One parent said when she and her husband secured one of the school choice scholarships for their son, "It was like we could breathe." (Photo courtesy of Heart Pine School.)

This is the latest post in our ongoing series on the center-left roots of school choice.

Gainesville, Fla. is a liberal college town that prides itself on being “green.” And if there’s a classroom that channels that vibe, it’s Wanda Hagen’s at Heart Pine School.

Hagen’s seventh graders raise tadpoles, hike in a park where buffalo lounge under live oaks, and hunt for shark’s teeth in Gainesville’s cherished urban creeks. On a whim, they might go for a stroll before a storm, to see if they can smell the change in the air. When children overcome the “nature deficit” of modern life, Hagen said, they and the planet benefit.

Plenty of folks in Gainesville would agree. And yet, the fingerprints of Gainesville progressives are all over two lawsuits that sees to end a school choice program that helps Heart Pine parents. Both take aim at the Florida tax credit scholarship for low-income and working-class students, which 26 of 62 Heart Pine students use.

Hagen, a self-described “independent liberal,” calls the suits “a real shame.”

“It’s Fahrenheit 451,” she said, referring to the classic novel about repression of dissent. If the lawsuits succeed, “The thinkers outside the box are not going to be appreciated.”

Heart Pine is another ripe example of the political left’s rift over school choice.

Despite a long history of center-left support, today’s progressives, especially white progressives, suffer from split personality disorder. Some still recoil from uniformity and bureaucracy. But others accept a warped view of school choice as a front for privatization, a position tied to the teachers union’s rise in Democratic Party politics. The ironic result is the biggest threat to a colorful school like Heart Pine, a school for grades 1-8 that follows the Waldorf model, isn’t conservatives. It’s fellow progressives.

In Gainesville, the fight pits neighbor against neighbor, even if neither side realizes it.

The lead plaintiff in the first lawsuit is Citizens for Strong Schools, a Gainesville group founded to push for higher property taxes for district schools. Its members include the president of the local teachers union, the spokesperson for the school district, and the woman who heads the Florida League of Women Voters’ “School Choice Project.” The plaintiffs are represented by Southern Legal Counsel, a Gainesville firm co-founded by Jon Mills, a high-profile Democrat and former Florida House Speaker. Their legal arguments are anchored in changes Mills helped engineer into a constitutional amendment that voters passed in 1998.

Filed in 2009, the suit blasts Florida’s entire education system, charging it has failed to live up to constitutional directives for “adequate” and “high-quality” schools. More funding is the big goal, but the plaintiffs are also firing at school choice programs, including the McKay Scholarship, which serves 31,000 students with disabilities, and the tax credit scholarship, which serves 95,000 students whose family incomes average 4 percent above poverty. (The latter is administered by nonprofits such as Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog and pays my salary.)

The second lawsuit trains its sights solely on the tax credit scholarship. It was filed in 2014 by the state teachers union and other plaintiffs, including the Florida League of Women Voters. In August, a three-judge panel of the First District Court of Appeal dismissed the suit, finding, like the circuit judge who did the same in 2015, that the plaintiffs provided no evidence to back claims of harm to public schools. The union requested last month that the Florida Supreme Court hear its appeal.

Many Heart Pine supporters want an alternative to mainstream schools, both public and private. Their school is housed in a former Presbyterian church, a replica of a Seminole chickee, covered with thatched palm, conspicuous on its playground. (more…)

The Netherlands decided nearly a century ago to end long-running religious strife over schools and let 1,000 flowers bloom. The Dutch system of universal school choice gives full government funding to public and private schools, including all manner of faith-based schools. (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

By common definitions, the Netherlands is a very liberal place. Prostitution is legal. Euthanasia is legal. Gay marriage is legal; in fact, the Netherlands was the first country to make it so. Marijuana is not legal, technically, but from what I hear a lot of folks are red-eyed in Dutch coffee shops, saying puff-puff-pass without looking over their shoulders.

Given the rep, it might surprise school choice critics, who tend to consider themselves left of center, and who tend to view school choice as not, that the Netherlands has one of the most robust systems of government-funded private school choice on the planet. Next year the system will reach the century mark, with nearly 70 percent of Dutch students attending private schools (and usually faith-based schools) on the public dime.

By just about any measure, the Netherlands is a progressive’s paradise. According to the Social Progress Index, it was the ninth most progressive nation in 2015, down from No. 4 in 2014. (The U.S. was No. 16 both years.) On the SPI, it ranked No. 1 in tolerance for homosexuals, and No. 2 in press freedom. On another index, the Netherlands is No. 1 in gender equality. (The U.S. is No. 42.) It’s also among the world leaders in labor union membership (No. 19 in 2012, with 17.7 percent, eight spots ahead of the U.S.). And by some accounts, Amsterdam, the capital, is the most eco-friendly city in Europe.

Somehow, this country that makes Vermont look as red as Alabama is ok with full, equal government funding for public and private schools. It’s been that way been since a constitutional change in 1917. According to education researcher Charles Glenn, the Dutch education system includes government-funded schools that represent 17 different religious types, including Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu and Rosicrucian, and hundreds that align to alternative bents like Montessori and Waldorf.

Glenn, an occasional contributor to redefinED, has written the book on the subject. He calls the Netherlands system “distinctively pluralistic.” (more…)

In 1968, Harvard sociologist Christopher Jencks, then a leading light of the Voucher Left, argued for universal school vouchers, primarily to benefit black students: " ... for those who value a pluralistic society, the fact that such a solution would, for the first time, give large numbers of non-Catholics a choice about where they send their children, ought, I think, to outweigh all other objections." (Image from www.hks.harvard.edu)

This is the latest installment in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

School vouchers won’t drain money from public schools, won’t violate the Constitution, and won’t fray the social fabric. Ultimately, they should be supported by “those who value a pluralistic society.” So wrote liberal Harvard sociologist Christopher Jencks, once a leading light on the Voucher Left, in a lengthy 1968 essay in the New York Times Magazine.

Oh, how times have changed.

Too many of today’s progressives boo and hiss at school vouchers, thinking they’re a Koch brothers weapon to kill public education. They should be reminded, as often as possible, that some of their left-of-center brethren (like him, him and him) see vouchers through a radically different lens and that, in fact, this progressive view goes back decades.

Jencks’s 1968 essay, “Private Schools for Black Children,” is yet more evidence. In the 1960s and ‘70s, Jencks led the team that tried, as part of a federal experiment, to field-test school vouchers in a California school district. He concludes in his NYT piece that vouchers are necessary for political reasons, even if he doubts it will move the ball academically for black students.

Today’s school choice supporters would respectfully disagree on the academic piece, and they have the benefit of evidence (like this, this and this) that wasn’t there 50 years ago. Also and obviously, there are plenty of other good reasons to restore parental power over education, like those thoughtfully laid out by Berkeley Law Professor Jack Coons.

Conclusion aside, what’s striking about Jencks’s essay is how he brushes aside so many anti-choice arguments that so many modern progressives embrace.

Don’t school vouchers defy constitutional restrictions separating church and state? No, Jencks says. At the time of his essay, the U.S. Supreme Court hadn’t ruled on that question. (It would, in favor of vouchers, in 2002). But, writes Jencks, it’s reasonable to think there wouldn’t be constitutional objections as long as the vouchers are “earmarked to achieve specific public purposes … “ Public money flows to Catholic hospitals and Catholic universities, he notes. Why not Catholic K-12 schools? The selectivity question continues to dodge scrutiny. (more…)

This is the all-in-one version of our recent serial about efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot. It's part of our ongoing series on the center-left roots of choice.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation.

***

Cue “Staying Alive.”

Disco was king. Jimmy Carter was president. And across the bay from Berkeley, the punk band Dead Kennedys was blasting its first angry chords. But in 1978, Coons and Sugarman still hadn’t gotten the carbon-copy memo that the ‘60s were over.

The ballot initiative they detailed in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice,” wasn’t gradual change, organic growth, nibbling at the edges.

It was revolution. (more…)

This is the latest post in our series on the progressive roots of school choice.

Credit James Forman Jr. with the best account yet of the center-left roots of the school choice movement. Credit his stint as a public defender for being the spark.

Forman, now a Yale law professor, said the district “alternative” schools serving his juvenile clients in Washington D.C. 20 years ago were giving them the least and worst when they needed the most and best. He began exploring options like charter schools, only to be told by some folks that school choice couldn’t be trusted because of its segregationist past.

Forman, now a Yale law professor, said the district “alternative” schools serving his juvenile clients in Washington D.C. 20 years ago were giving them the least and worst when they needed the most and best. He began exploring options like charter schools, only to be told by some folks that school choice couldn’t be trusted because of its segregationist past.

Forman knew about the “segregation academies” some white communities formed to evade Brown v. Board of Education. But he knew that wasn’t the whole story. Among other reasons, he was the son of James Forman, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the group whose courageous members became known as the “shock troops” of the civil rights movement.

Wait, he thought, recalling stories his parents told him about Mississippi Freedom Schools. Wasn’t that school choice?

“It seemed impossible to me to think that over all of those years, African-Americans had never organized themselves to try to create better (educational) opportunities outside what the state was providing them,” Forman told redefinED in the podcast interview below. “So that was my idea. My thesis was there had to be an alternative history, there had to be a history of African Americans who were not relying on the government and were trying to organize themselves to create schools to educate their children.”

The result of Forman’s research is “The Secret History of School Choice: How Progressives Got There First.”

The 2005 paper traces the progressive movement for educational freedom from Reconstruction, to the civil rights movement, to the “free schools” and “community control” movements of the 1960s and ‘70s. A century before many activists were using the term “school choice,” it notes, black churches were making it happen. Decades before conservative Gov. Jeb Bush was pushing America’s first statewide voucher program, liberal intellectuals were promoting the notion in The New York Times Magazine.

A decade later, “The Secret History of School Choice” remains a must-read for anyone who wants a fuller, richer picture of choice’s beginnings. But Forman, who co-founded a charter school named for Maya Angelou, hopes progressives in particular see the light.

They ignore the history of school choice, and their role in shaping it, at their own peril, he said. Believing, wrongly, that it’s right-wing can result in it becoming just that. If progressives aren’t at the table, he suggested, they can’t bring their values to bear in shaping policy. In his view, it’d be good if they did. (more…)

This is the second post in our series on the Voucher Left.

Way back in 1978, when Bee Gees ruled the radio and kids dumped pinball for Space Invaders, a couple of liberal Berkeley law professors were promoting a variation on “universal” school vouchers that they believed would ensure equity for the poor. Along the way, they foreshadowed a revolutionary twist on parental choice that would make national headlines nearly four decades later.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman didn’t use the term “education savings accounts” in their book, “Education by Choice.” But they described a sweeping plan for publicly funded scholarships in terms familiar to those keeping tabs on ESAs. They envisioned parents, including low-income parents, having the power to create “personally tailored education” for their children, using “divisible educational experiences.”

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman didn’t use the term “education savings accounts” in their book, “Education by Choice.” But they described a sweeping plan for publicly funded scholarships in terms familiar to those keeping tabs on ESAs. They envisioned parents, including low-income parents, having the power to create “personally tailored education” for their children, using “divisible educational experiences.”

To us, a more attractive idea is matching up a child and a series of individual instructors who operate independently from one another. Studying reading in the morning at Ms. Kay’s house, spending two afternoons a week learning a foreign language in Mr. Buxbaum’s electronic laboratory, and going on nature walks and playing tennis the other afternoons under the direction of Mr. Phillips could be a rich package for a ten-year-old. Aside from the educational broker or clearing house which, for a small fee (payable out of the grant to the family), would link these teachers and children, Kay, Buxbaum, and Phillips need have no organizational ties with one another. Nor would all children studying with Kay need to spend time with Buxbaum and Phillips; instead some would do math with Mr. Feller or animal care with Mr. Vetter.

Coons and Sugarman were talking about education, not just schools, in a way that makes more sense every day. They wanted parents in the driver’s seat. They expected a less restricted market to spawn new models. In “Education by Choice,” they suggest “living-room schools,” “minischools” and “schools without buildings at all.” They describe “educational parks” where small providers could congregate and “have the advantage of some economies of scale without the disadvantages of organizational hierarchy.” They even float the idea of a “mobile school.” Their prescience is remarkable, given that these are among the models ESA supporters envision today.

It's also noteworthy given a rush to portray education savings accounts as right-wing.

In June, for example, the Washington Post described the creation of the near-universal ESA in Nevada as a “breakthrough for conservatives.” School choice would likely be a top issue in the 2016 presidential campaign, the story continued, with leading Republicans like Jeb Bush, Scott Walker and Marco Rubio all big voucher supporters and Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton opposed. The story pointed out Milton Friedman’s conceptualizing of vouchers in 1955, then added, “The idea was long thought to be moribund but came roaring back to life in 2010 in states where Republicans took legislative control.”

It’s true that in Nevada, Republicans took control of the legislative and executive branches in 2014, and then went on to create ESAs. But it’s also true that across the country, expansion of educational choice has been steadily growing for years, and becoming increasingly bipartisan in a back-to-the-future kind of way. Nearly half the Democrats in the Florida Legislature voted for a massive expansion of that state’s tax credit scholarship program in 2010. About a fourth of the Democrats in the Louisiana Legislature voted for creation of that state’s voucher program in 2012. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has been fighting for a tax credit scholarship in that bluest of blue states – an effort in which he’s joined not only by many other elected Democrats, but by a long list of labor unions.

These Democrats are sometimes accused of being sellouts – often by teachers unions and their supporters, who have been especially critical of Cuomo. But the truth is, they can draw on a rich history of support for educational choice grounded in the principles of the American left.

The recent history of ESAs isn’t quite as polarizing as the Post suggests, either. (more…)

An influential black minister endorsed Republican New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie this week because of the governor’s support for school vouchers. In doing so, Bishop Reginald Jackson also offered a harsh assessment of the Democratic Party.

“It is sad for me to see my party, which embraced the civil rights movement, now in New Jersey blocking low-income and minority children from escaping the slavery of failing schools,” Jackson said, according to several news outlets. Of black Democratic lawmakers in particular, he added, “Every day, they see children who are not getting a quality education and that doesn’t seem to move them.”

In an interview with redefinED, Jackson went further. Many black Democratic lawmakers “have placed the special interests above the interests of their constituents," he said in the podcast attached below. "The unions … have more influence and more bearing on them than the children who live in their districts.”

Bishop Jackson is a household name in New Jersey and often considered the state’s most powerful black leader. His resume includes a long list of progressive causes. He led efforts to deter racial profiling by state police and predatory lending by banks. He worked to secure more funding for public schools. Asked if supporting school choice was in line with Democratic values, Jackson said, “School choice is in fact an America value.”

His comments come as New Jersey lawmakers continue to beat back efforts to expand school choice while their counterparts in other states – Democrats included – are warming to them.

The key to getting more Democrats to come around, Bishop Jackson said, is educating parents about where Democrats stand. “They have to become aware that the folk whom they’ve elected to represent them right now do not have their children as their No. 1 interest,” he said. “Once we are able to open up their eyes so they can see this, then hopefully they will make better choices in terms of who they put in the Legislature.”

If that means more black voters going Republican, he suggested, so be it.