The future of education is happening now. In Florida. And public school districts are pushing into new frontiers by making it possible for all students, including those on education choice scholarships, to access the best they have to offer on a part-time basis.

That was the message Keith Jacobs, director of provider development at Step Up For Students, delivered on Excel in Education’s “Policy Changes Lives” podcast A former public school teacher and administrator, Jacobs has spent the past year helping school districts expand learning options for students who receive funding through education savings accounts. These accounts allow parents to use funds for tuition, curriculum, therapies, and other pre-approved educational expenses. That includes services by approved district and charter schools.

“So, what makes Florida so unique is that we have done something that five, 10, even, you know, further down the line, 20 years ago, you would have never thought would have happened,” Jacobs said during a discussion with podcast host Ben DeGrow.

Jacobs explained how the process works:

“I’m a home education student and I want to be an engineer, and the high school up the street has a remarkable engineering professor. I can contract with the school district and pay out of my education savings account for that engineering course at that school.

“It’s something that was in theory for so long, but now it’s in practice here in Florida.”

It is also becoming more widespread in an environment supercharged by the passage of House Bill 1 in 2023, which made all K-12 students in Florida eligible for education choice scholarships regardless of family income. According to Jacobs, more than 50% of the state’s 67 school districts, including Miami-Dade, Orange, Hillsborough and Duval, are either already approved or have applied to be contracted providers.

That’s a welcome addition in Florida, where more than 500,000 students are using state K-12 scholarship programs and 51% of all students are using some form of choice.

Jacobs said district leaders’ questions have centered on the logistics of participating, such as how the funding process works, how to document attendance and handle grades.

Once the basics are established, Jacobs wants to help districts find ways to remove barriers to part-time students’ participation. Those could include offering courses outside of the traditional school day or setting up classes that serve only those students.

Jacobs said he expects demand for public school services to grow as Florida families look for more ways to customize their children’s education. That will lead to more opportunities for public schools to benefit and change the narrative that education is an adversarial, zero-sum game to one where everyone wins.

“So, basically, the money is following the child and not funding a specific system. So, when you shift that narrative from ‘you're losing public school kids’ to ‘families are empowered to use their money for public school services,’ it really shifts that narrative on what's happening here, specifically in Florida.”

Jacobs expects other states to emulate Florida as their own programs and the newly passed federal tax credit program give families more money to spend on customized learning. He foresees greater freedom for teachers to become entrepreneurs and districts to become even more innovative.

“There is a nationwide appetite for education choice and families right now…We have over 18 states who have adopted some form of education savings accounts in their state. So, the message to states outside of Florida is to listen to what the demands of families are.”

A district makes a painful decision to close school plagued by persistent low performance and low enrollment.

Fortunately, the closest school is a high-performing, highly sought-after affluent urban enclave. Unfortunately, most students affected by the closure won't have access to that school. Instead, they will wind up in nearby schools with lower achievement levels and more space to fill.

This is the crux of the story of Tampa's Just Elementary, as rendered by Tim DeRoche in The 74.

DeRoche, the founder of a new advocacy organization devoted to equalizing access to public schools, argues convincingly that assigning students to schools based on where their parents can afford to live is anathema to the ideal articulated 69 years ago by the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education that public schools must be available to all on equal terms.

School districts in cities like New Orleans have made nearly all public schools open to all students, and set rules assuring students affected by school closures receive priority access to other public schools. The disruption of closures can be painful, and research shows the quality of the schools where affected students wind up can be crucial to their academic trajectories.

The problem in Hillsborough County is that many of the well-regarded public schools are full, and the parents who paid exorbitantly through the housing market for the privilege of a guaranteed spot are unlikely to yield their exclusive access.

The solution, DeRoche argues, is to break the link between geography and school assignment. He concludes: "School access needn’t be a zero-sum game governed by bitter political fights over maps."

Embracing public school open enrollment and eliminating geographic assignment are essential, but they may not be enough to end the zero-sum game on their own. In school systems that have created large numbers of public-school options that break the link between the housing market and school access, the wealthy and well-connected seek other ways to rig the game. A few years ago, former D.C. Public Schools Chancellor Antwan Wilson illustrated this reality when he attempted to bypass a public school's admissions lottery and wound up losing his job.

To create a positive-sum game, we need to confront an under-appreciated enemy of progress in education: Scarcity.

Some public universities are working to break scarcity's stranglehold. Over the past 10 years, my alma mater, the University of Florida, has grown its enrollment by about 20 percent, adding roughly 10,000 students. Half of that growth has occurred at its traditional brick-and-mortar campus. The other half has come through a new online program. And the university is experimenting with other models that would allow it to serve more students, while creating flexible opportunities that fit their lives. Its new Innovation Academy serves nearly 1,000 students who attend classes during the spring and summer, but free up their fall semester to pursue passion projects.

These efforts are in their early days, but the same principle should apply in public education: Make opportunities abundant. Highly sought-after institutions should look for ways to serve as many students as possible. They can do this by making flexible use of technology, time, and space.

What could this look like in a school district like Hillsborough County, where some highly sought-after schools are over-enrolled, but others struggle to fill their available space with students? Here are three ideas:

Use the flexibility of online learning to serve more students. Gorrie Elementary, the highly sought-after school with costly surrounding real estate prices, may not be able to follow every aspect of UF's playbook and reach more students through online learning. Full-time virtual school just isn't a good fit for many elementary-aged students. But experimenting with models that combine online learning with in-person support could allow over-enrolled schools for older kids, like Plant High School, to serve more students without needing to build more classrooms.

Share space in existing public schools. In school districts like Denver and Mesa, Arizona, districts have invited microschools to share space in their buildings.

Small learning environments gain access to district facilities. Their students gain opportunities to interact with larger peer groups without sacrificing the intimacy and individual attention that drew them to microschools in the first place.

Districts, meanwhile, can fill space in underused buildings, offer more innovative programs to their students, and attract families (and revenue) that might otherwise leave the district for private schools or homeschooling.

Reimagine where and when students learn. District schools could also draw inspiration from UF's Innovation Academy, and rethink conventional assumptions about what the school calendar looks like, or where and when learning happens. Florida's new part-time enrollment law allows students to enroll in district programs that don't use the full day or year. Other learning opportunities could fill the remaining space on the calendar. A school near downtown Tampa could treat the city as an extended classroom, partnering with the Florida Aquarium, Glazer Children's Museum, and other nearby institutions to provide learning experiences to students who also spend time in traditional classrooms. A field trip to the museum or the aquarium could be the highlight of a student's year. Why limit it to a single day?

This combination of opening more spots in sought-after schools to more students and filling under-enrolled schools with more diverse learning options has the potential to make high-quality learning opportunities more abundant. It may be the only way to detoxify the zero-sum politics that typically surround school assignment.

Districts that commit to creating abundant opportunities will likely bump into state laws that hold them back. New legislation passed this year kicks off a process to identify these barriers so state policymakers can address them, and the Florida Department of Education is taking suggestions.

In the meantime, as my colleague Ron Matus points out, there are private schools in the vicinity of the closed Just Elementary run by highly qualified Black educators that, thanks to the expansion of state scholarship programs, are able to serve students of all incomes.

School districts in Florida have a unique advantage compared to their counterparts in other states: Enrollment, statewide and in most districts, is growing, in both public and private schools. Eventually, declining birth rates and shifting migration patterns may catch up with our state, too. There is no time like the present to create abundant opportunities for everyone.

Image credit: "A visit to the Florida Aquarium" by LimpingFrog Productions is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Great Hearts Northern Oaks in San Antonio, Texas, is part of a system of state-chartered public schools that offer a tuition-free, liberal arts education rooted in the literary and philosophical tradition of the West. Great Hearts Northern Oaks students learn about historical events, literary characters, poetry, scientific facts and mathematical proofs.

Editor’s note: This analysis from Cassidy Syftestad, a doctoral academy fellow in the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, and Albert Cheng, an assistant professor in the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, appeared Thursday on The Fordham Institute’s website.

Recent shifts in enrollment patterns across Texas school sectors have gone in one direction—out of traditional public schools. Within those shifts, a disproportionately large swath of students has left for classical charter schools.

These trends reflect a wider renaissance of classical schooling across the United States. Parents from all manner of backgrounds increasingly sought out classical schools during the pandemic, but also beforehand. And that trend appears to be continuing.

In a new report, we use data from the Texas Education Agency and the National Center for Education Statistics to uncover exactly how much classical charters have grown in Texas since 2011 and the reasons behind such growth.

Texas is home to several classical charter schools. Great Hearts, Valor, and ResponsiveEd operate networks throughout the state. Other classical charters such as Houston Classical and Trivium Academy, though not part of larger networks, are well known in their respective communities.

What do these schools have in common? As Jennifer Frey explains on the Flypaper blog:

On this model, to become educated is, at least in part, to become a person of good character—to become habituated into recognizable patterns of correct thinking, acting, and feeling so that one is disposed to judge and choose well on the whole, in order to live a purposeful and meaningful life that contributes to the common good.

As depicted in Figure 1, Texas’s charter sector has grown dramatically in the past decade. However, the most prolific growth within the sector appears to be concentrated among classical charter schools. While enrollment in other Texas charters doubled between 2011 to 2021, enrollment in Texas classical charter schools increased nearly sevenfold to 20,000 students over the same period. Several thousand students remain on waitlists for seats in them.

The classical charter sector also grew along ethnic lines, with the most pronounced increase for Asian American (a thirteenfold increase) and Hispanic students (a ninefold increase).

To continue reading, click here.

Imagine School at Broward is a tuition-free public charter school in Coral Springs, Florida, one of 712 charter schools in the state serving about 360,000 students. Imagine Schools is a national non-profit network of 51 schools in seven states and the District of Columbia.

Editor’s note: This analysis of a study conducted by the Center for Research on Educational Outcomes at Stanford University appeared Tuesday on edweek.org.

A new study shows that charter school students are now outpacing their peers in traditional public schools in math and reading achievement, cementing a long-term trend of positive charter school outcomes.

The study is the third in a series conducted by the Center for Research on Educational Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University, which has researched charter school performance since 2000. The third study, released June 6, is notable because it shows superior outcomes among charter school students while the center’s earlier studies showed charter school students performed either worse than or about the same as their peers in traditional public schools.

The researchers used standardized testing data from over 1.8 million students at 6,200 charter schools to determine how student learning at the schools compares to traditional public schools.

The most recent study covers student learning from 2014 to 2019. Its previous studies covered 2000-01 through 2007-08 and 2006-07 through 2010-11. CREDO’s study of that first period, released in 2009, found that charters failed to meet traditional public school outcomes.

The 2023 study reversed that narrative and showed that charters have drastically improved, producing better reading and math scores than traditional public schools. The results are “remarkable,” said Margaret “Macke” Raymond, founder and director of CREDO.

“The bigger lesson now in the post-COVID world is, hey guys if you’re looking for a way to improve outcomes for kids, here is an absolutely demonstrated framework that you can look at and maybe apply it in other contexts,” Raymond said.

Raymond said the improvement has come largely from existing schools tweaking their practices over time and getting better as a result—"evolution” rather than “revolution.”

To continue reading, click here.

When the doors of the former Warrington Middle School open in August, students will enter a new School of Hope.

When the doors of the former Warrington Middle School open in August, students will enter a new School of Hope.

Members of the State Board of Education unanimously approved Renaissance Charter School’s application to be a School of Hope operator in Escambia County, the westernmost county of the Florida Panhandle. Renaissance, a non-profit organization, is managed by Charter Schools USA, a for-profit company based in Fort Lauderdale that serves 100 charter schools across the United States.

The approval came a week after the Escambia County School Board approved a contract with Charter Schools USA and Renaissance to take over operations at Warrington Middle School, which has struggled academically for more than a decade and has not received a state grade higher than a D during that time.

The designation, allowed by a law passed in 2017, includes several conditions that allow charter operators to be named Schools of Hope. Those include charter schools that are approved to take over struggling district schools that are in the state turnaround process. It also gives the charter operators access to additional state funding.

The most recent designation in this category was granted to Somerset Academy, Inc., which took over the Jefferson County School District in 2017 after the district’s long string of failing state grades. After its five-year contract ended, Somerset turned the schools back over to district officials.

“This is not just a name; it’s just not a designation with bragging rights,” said Adam Emerson executive director of the Florida department of Education’s Office of Independent Education and Parental Choice. “It also does come with some significant resources, startup resources, that can get help get them off the ground for a successful start this fall because the first day of school is only a few months away.”

Emerson said the state education department would take an active role in helping Renaissance Charter School as it reopens the former Warrington Middle campus and will provide updates at each monthly state Board of Education meeting.

“This has been the bane of our existence for quite some time,” board member Monesia Brown said. She pointed out that the district’s messaging during the contract negotiation process had been primarily negative and asked that future communications from the state reassure parents that “this is an investment to make sure their children get the quality of education they deserve.”

The approval of the contract between the Escambia County School District and Charter Schools USA marked the end of two months of tense negotiations over the school’s future enrollment policies, fees and long-term lease issues.

District leaders also faced the wrath of state officials and board members who criticized them for failing to make progress in reaching an agreement with the charter organization.

In a surprise move shortly after voting to approve the contract, the Escambia County School Board fired the superintendent.

Emerson said now that the contract has been signed, the community is coming together, and that a recent meeting “struck a collaborative tone to move forward.”

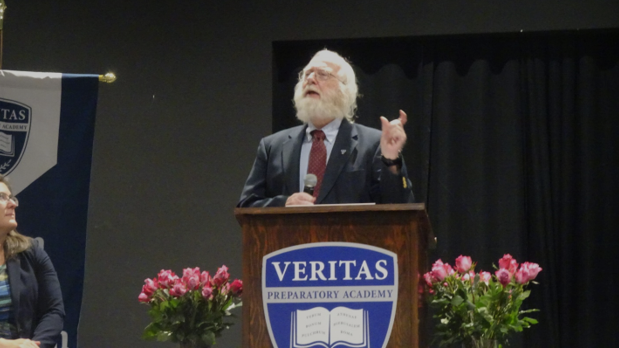

Mike Sullivan, who taught Classical Languages and Humane Letters at Veritas Preparatory Academy for 20 years, retires at the end of this school year. Before coming to Veritas, he was a private practice attorney and served the University of Minnesota in its Student Legal Services department after serving in the U.S. Army Intelligence corps as a translator and interpreter.

Veritas Preparatory Academy, a founding member of the prestigious Great Hearts Academy in the Phoenix metropolitan area, held a joyous retirement ceremony for one of its founding faculty members, Mike Sullivan, on May 20. Great Hearts recruited Sullivan, a 60-year-old attorney living in Wisconsin, to teach Latin and Greek.

Sullivan had enjoyed a career in the military followed by a legal career before finishing strong in the classroom for two decades. His most recent career holds a valuable lesson for policymakers.

Students, colleagues, and students who went on to became colleagues all related fond memories and valued lessons imparted by beloved sage-curmudgeon during the event. Veritas Prep’s first headmaster, Andrew Ellison, told of hosting the visiting Sullivan on a recruiting visit.

Ellison felt a growing sense of desperation over the course of the day, thinking he just had to have Sullivan join the faculty. Sullivan at one point told Ellison that he had been waiting all day for Ellison “to say something wrong” so he could get on a plane and go back to Wisconsin.

“But it hasn’t happened yet, and I don’t think it’s going to happen,” Sullivan said. Ellison described this as “the moment Veritas Prep was born.”

Policy decisions impact lives, sometimes in incredibly positive ways. It is worth noting that many states would not have allowed Mike Sullivan to launch his second career in teaching without jumping through a number of useless hoops. And, yes, I can demonstrate the uselessness of the hoops.

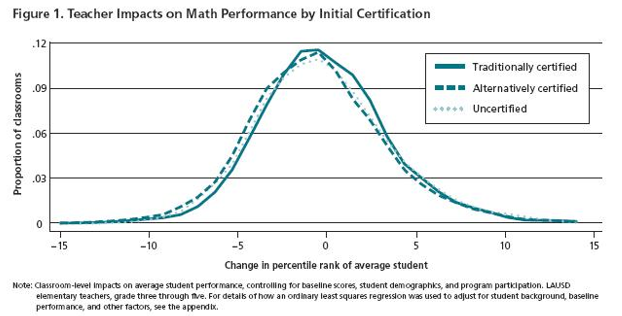

If you look very, very closely at this chart that comes from a study of student learning gains conducted by the Brookings Institution, you will see a dotted curve along with the line and dash curves. The three curves show the learning gains/declines from the students of traditionally certified teachers (the line curve), alternatively certified teachers (the dash curve), and finally from uncertified teachers (the dot curve).

If you look very, very closely at this chart that comes from a study of student learning gains conducted by the Brookings Institution, you will see a dotted curve along with the line and dash curves. The three curves show the learning gains/declines from the students of traditionally certified teachers (the line curve), alternatively certified teachers (the dash curve), and finally from uncertified teachers (the dot curve).

Notice the lack of any meaningful difference in the overall curves; they all have highly effective teachers and highly ineffective teachers. But also note the difference between a right side of the bell-curve teacher and left-side is gigantic. As explained by the authors of the Brookings study:

Moving up (or down) 10 percentile points in one year is a massive impact. For some perspective, the black-white achievement gap nationally is roughly 34 percentile points. Therefore, if the effects were to accumulate, having a top-quartile teacher rather than a bottom-quartile teacher four years in a row would be enough to close the black-white test score gap.

Arizona lawmakers wisely gave charter school leaders the flexibility to recruit from any of the three curves in search of highly effective instructors. Ipsi prudenter elegerunt!

Veritas Prep found Mike Sullivan practicing law in a distant state and had the flexibility to coax him into a next great career. The adoration of Sullivan’s students and colleagues seems like a much greater compensation than any provided by a law firm.

More Sullivan-like instructors are likely awaiting discovery at some unexpected place. Find them and get them in the classroom!

Blue River Career Programs in Shelbyville, Indiana, offers career training certification programs in construction, nursing, and child development.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Monday on in.chalkbeat.org.

Loriann Beckner can’t imagine the idea of going to nursing school without her internship. A senior at Southwestern High School in Shelbyville, Beckner interns at a hospital, Major Health Partners, through the work-based learning program at Blue River Career Programs.

Working with Blue River instructor Ray Schebler, she’s learned about financial literacy and career development skills that she says she would not have learned otherwise, in addition to what she learns at the hospital.

“He’s taught me how to do interviews and so [much] workplace learning stuff that my high school never would’ve taken the opportunity to teach me,” Beckner said. “I just think without my internship, I’d be super scared.”

But the future of Blue River — one of 52 career centers across the state that offers high schoolers academic credits, industry certifications, and more — has been thrown into doubt this year after Indiana lawmakers enacted a law that creates Career Scholarship Accounts.

These will provide funding for students to pay for internships and apprenticeships with local employers without necessarily relying on current career and technical education programs.

GOP lawmakers said the law, which Republicans said would be a top priority this year, will help “reinvent” high school in response to declining college enrollment and evolving employer needs. They also say the accounts will make career training more accessible.

Critics worry these new accounts will hurt programs like Blue River and the public schools that partner with them to provide career and technical training, without truly providing new or additional benefits.

The Career Scholarship Accounts are part of a push by state leaders to shift some authority and funding away from traditional public schools and educators to constituencies like parents and the business community.

To continue reading, click here.

With the clock ticking on a state-imposed 48-hour deadline and the threat of withheld salaries hanging over their heads, Escambia County School Board members on Tuesday approved a contract with a charter school operator to take over a struggling middle school.

With the clock ticking on a state-imposed 48-hour deadline and the threat of withheld salaries hanging over their heads, Escambia County School Board members on Tuesday approved a contract with a charter school operator to take over a struggling middle school.

Board members voted 4 to 1 in favor of the contract, which allows Charter Schools USA to assume operations in the upcoming school year at Warrington Middle School, which has never received a state grade higher than a D for the past decade.

Board members who voted in favor of the measure were clear they did so reluctantly.

“I really hurt today,” board member Patty Hightower said. “We have never equivocated on the fact that we have never been successful at Warrington Middle School. But it’s not because of the people who work there. The people have given their blood, sweat and tears to work with these students. It’s not because they didn’t try. It’s not because they are incompetent.”

However, she added, “Charter schools are public schools. Some of the things they are asking for in this agreement are normal charter school requests. I’m willing to give Charter Schools USA a chance, and so I will be voting to support the agreement.”

The other three board members who voted with her said they thought they had no choice given the state’s ultimatum and that it was better than closing the school and busing all the students to other middle schools.

“This is the best thing at the moment for the students in the Warrington zone,” board member Bill Slayton said. “We’ve been given 48 hours; that’s why I’m saying let’s give it to them. We have tried for 10 years or longer.”

The Escambia County School Board vote followed a contentious conference call earlier in the day of the state Board of Education, in which members leveled harsh criticism at the Escambia County district leadership. State board members voted unanimously in favor of Florida Commissioner of Education Manny Diaz Jr.’s recommendations, which were the following if the district failed to sign an agreement with Charter Schools USA within 48 hours.

Report the school district to the Florida Legislature for failing to comply with state law.

Withhold funding to the district equal to the salaries of the superintendent and school board members.

Require the district to provide the state Department of Education with daily progress reports on its negotiations with Charter Schools USA.

“You’ve been failing the children of Warrington Middle School for the past decade,” Diaz told Escambia School Superintendent Tim Smith and School Board Chairman Paul Fetsko, who represented the district on the call.

Diaz said he found the district’s recalcitrance in correcting the situation “shocking” that district had yet to reach an agreement with Charter Schools USA, which it chose last year to take over Warrington Middle School. “This is not a new issue.”

State board Vice Chairman Ryan Petty accused the school district leaders of being “incompetent and completely disingenuous” in their handling of the matter.

“It’s been well over a year, and while I understand there were critical issues during the negotiations, you have had over a year to get these things resolved, and you come in here telling us just now that in the last couple of days you’ve been unable to resolve this,” Petty said.

Smith said the district board held an emergency meeting Friday but did not receive any response from Charter Schools USA about its counteroffer until later in the day. He said there had been some confusion as to whether Warrington students would be guaranteed seats at the charter school. Charter Schools USA said in its counteroffer on May 5 that 200 students from the Warrington zone in sixth through eighth grades would be guaranteed seats when the charter opened this year.

School officials had said throughout the negotiation process that their biggest concern was that students living in the Warrington zone would have a neighborhood middle school.

Warrington Middle first entered the state’s turnaround process in 2012 under a district-managed plan. However, when test scores did not improve, the state gave the district until 2020-21 for Warrington to reach a state grade of at least a C. During that year, the state allowed schools to forgo reporting test scores because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

When the district did report scores in 2021-22, Warrington Middle remained at a D. The state board then ordered the district turn it over to a charter company by May 1. You can see a complete history and update of its turnaround plan here.

District officials began negotiating in November with Charter Schools USA, which serves 75,000 students in five states. The 26-year-old charter school operator was the only organization to express interest in taking over the Title 1 school, where 80% to 90% of its approximately 600 students live below the federal poverty line.

The parties appeared to be headed toward a May 1 deadline to forge an agreement. However, negotiations hit a snag when district leaders said at an April 13 school board meeting that Charter Schools USA had sent a list of conditions for it to make a long-term commitment to the school. Those included the charter company becoming a K-12 charter with open enrollment by 2026-27.

Other points of conflict had been the charter company’s request for 100% of the district’s 1.5 mil local taxes for capital projects and the district’s request that the charter school pay the district a 5% administrative fee; the charter company said they should not have to pay the fee.

On Tuesday night, Fetsko expressed his feelings about Diaz, the state Board of Education and Charter School USA.

“I have great disdain for the business practices of Charter Schools USA,” he said. “The commissioner showed himself to be a very unreasonable man. State board members showed themselves to be nothing but a bunch of magpies reporting what they’ve been told to say. At one time I had great respect for the Department of Education. That has changed.”

Though Fetsko said he would vote for the contract, he said the district should find a way to way to “make sure this never happens again.”

“Build a system of K-8 or something to cause our students to stay with us, to not choice into a charter and not leave what’s going on and show we can educate our own and we don’t need somebody being pushed upon us.”

Shortly after the vote to approve the contract with Charter Schools USA, the school board voted 3-2 to fire the superintendent, citing resignations, staff shortages, and a lack of communication regarding the contract with Charter Schools USA. Smith’s contract ends May 31. The board appointed an assistant superintendent as interim.

Elevate Charter Academy in Caldwell, Idaho, occupies a state-of-the-art, 55,000-square-foot building designed by professionals in the areas of culinary arts, construction, welding, manufacturing, medical arts, criminal justice, firefighting, business, marketing, and graphic design.

As National Charter Schools Week draws to a close, reimaginED presents this first-person essay from Domionique Valenzuela, a charter school graduate and member of the 2023 Future Leaders Fellowship with the American Federation for Children. You can read more about Valenzuela here.

Domionique Valenzuela

If you had told me three years ago that I would be at this point in life – with my diploma, a certificate in culinary arts, and a certificate in business services – all because of a charter school, I wouldn't have believed you.

But that’s exactly what happened, and my experience is why I am so motivated to make sure other students have the chances I did. This year during National Charter Schools Week, I am sharing my experience so that others might know the endless opportunities these choices can bring.

For as long as I can remember, I had a tough time in school. I struggled with reading and writing for years. My family moved around a lot, so I was constantly in and out of different schools. The public schools I went to were good for some students, but they were never able to help me in the way I needed.

Often, what I needed most was just support and encouragement.

As my freshman year approached, because of where I lived, there were no other options for my schooling other than my local public high school. I never felt so diminished in my life as during that year. I was tired of feeling like I didn't know anything.

I couldn't turn to my teachers for support because they had already determined my value and decided my time was better spent in suspension than in the classroom.

I was tired of being told I was so far behind I couldn’t catch up, that I wouldn't even come close to graduating. It was hurtful, but even worse, I had started to believe it, that I wouldn't make it and wasn't going to graduate and build the life I had dreamed of.

Luckily, at the beginning of my sophomore year, Elevate Academy in Caldwell, Idaho, part of the Boise metropolitan area, had opened. When my family found out about this option, I immediately transferred. Elevate is a public charter school that involves trades in its curriculum. I remember my first day; it was hard. I didn't trust my teachers because of experiences at my old high school, and working past that was a challenge.

It took some adjusting and getting to know my teachers until I realized that they cared about me, about all of us. They took so much time and energy and invested it into our success. Most of my classmates came from the same school I had come from. We were tired, and we all felt the same way: dumb. No student deserves to feel that way, but we did. We were all behind, and if we had stayed, most of us would have failed or dropped out.

Elevate provided the hope for us to get another chance to be something in life, not just prove everyone who had shamed us right. At Elevate, we had teachers supporting us, and we were a close-knit group ourselves. We weren't going to let each other fall behind.

Not only did Elevate give me the strength to believe in myself and graduate, but it also gave me the love I didn’t realize I had for learning. It’s a great feeling wanting to come to school because you have a responsibility and know people are counting on you. Elevate was able to make me feel that way with my education, and it changed everything.

During sophomore year, we learned about the different trades to determine what we wanted to pick for the next year, and we got a helpful visual learning experience. In math, we were told we had to design a building on paper, and we decided on a shed. It needed doors, windows, and a roof.

The construction teacher used an app, and we were able to build and sell our building! Later, when we took business, we had to find a real lot on which to place our hypothetical building, make sure it complied with city laws, and have some type of nonprofit or business to occupy it. Experiencing a more hands-on approach to education was like entering a new world, and it was one in which I thrived.

During junior year, I was able to pick two trades to learn and focus on for the next two years. I decided that my primary would be business services, and secondary would be culinary arts. During that time, I was the business manager of the construction trade, and members of the public could use our services.

The construction team built a doghouse, sheds, fences, and so many other creations. I had the experience of calling the customers, talking to them about pricing, billing them, and everything else that goes along with managing businesses. For culinary arts, we managed catering, school coffee shops, bakery fundraisers, teacher lunches, and more. We were the real-life faces of the businesses, and we students had a responsibility to be there – and we wanted to be!

My experience shows just one small part of the endless opportunities that innovative educational options can bring. For me, choosing Elevate was choosing success for my future. I graduated in 2022, and I’m learning the demands of my current job to take ownership of it, along with continuing my education, taking a competitive internship, and more. All of this – for a student who was told she would fail.

The U.S. Congress as well as individual states should support charter schools because every student deserves these chances.

Arizona Autism Charter School in Phoenix is the first and only tuition-free, public charter school in the state focused on the educational needs of children with autism. Serving families on two campuses, the school has been recognized nationally for excellence and innovation, winning the prestigious Yass Prize in 2022.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Nina Rees, president & CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, appeared Sunday on the74million.org to mark Teacher Appreciation Week, which coincides this year with National Charter Schools Week.

Remember the teacher who made a difference in your life? For me, that was Mrs. Campbell, my AP French teacher.

As an immigrant for whom English was not a first language, Mrs. Campbell offered me a chance to excel while my other classes were more daunting. Her class was also where I felt most at ease and supported. Mrs. Campbell found ways to shine a positive light on me in this large, rural high school, and when it came time to apply to college, she was the advocate who reached out to the admissions office to ensure my application got serious consideration.

Today, more than 35 years (yikes!) after I sat in her classroom, Mrs. Campbell continues to inspire me. I’ve dedicated my career to improving education policy. I wake up every day working to make public education better, not just for students and families, but for teachers like Mrs. Campbell who know that offering options helps all families.

I’m thrilled that National Charter Schools Week coincides with Teacher Appreciation Week this year, because charter schools are powered by teachers and other visionary educators who make a huge difference in the lives of more than 3.7 million students — two-thirds of whom are from low-income, Black, or Latino communities.

Teacher quality is the single biggest in-school factor in determining student success. There’s lots of fluffy talk about how important teachers are, but most of the time they are treated like identical cogs in a wheel. Charter schools do it differently.

Public charters offer an environment that encourages teachers to flourish, treats them like professionals and rewards their excellence through competitive pay and advancement opportunities. This allows them to chart their own course, whether it’s dedicating themselves to the classroom, moving into leadership roles or opening their own schools.

Charter schools also rely on teachers’ judgment about what works for students and what doesn’t, providing the flexibility to adapt curriculum and instruction as needed.

One of the key reasons charter schools were created was to give educators the freedom to test new ways of teaching. It’s also one of the reasons the late Albert Shanker, leader of the American Federation of Teachers, supported charter schools. Even Randi Weingarten, president of the AFT, is a charter school founder.

Today, the sector boasts more than 206,000 teachers — and the National Alliance of Public Charter Schools is especially proud that these educators reflect the diversity of the students they teach. The most recently available data (2020-21 school year) show that 69.3% of charter school students were children of color, compared with 53.4% of district students.

To continue reading, click here.