National Charter Schools Week is upon on us, which is an excellent time to review the differences between awesome and less than awesome charter school sectors.

National Charter Schools Week is upon on us, which is an excellent time to review the differences between awesome and less than awesome charter school sectors.

Charter schools have an intrinsic value in providing new opportunities and in creating competitive effects, but geographically inclusive charter sectors might have the additional benefit by encouraging district open enrollment. Suburban charter schools may be force multipliers because they can create a powerful incentive for suburban districts to participate in open enrollment. Private choice can do the same.

After one suburban district participates in open enrollment, it increases the incentives for others to do the same. Before you know it, all districts may participate.

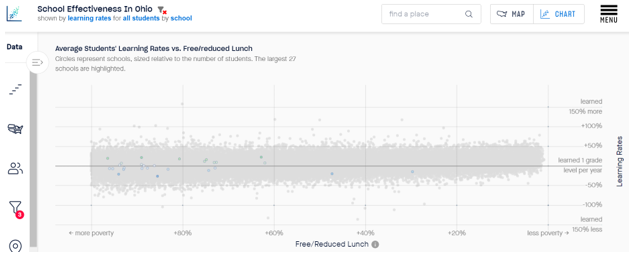

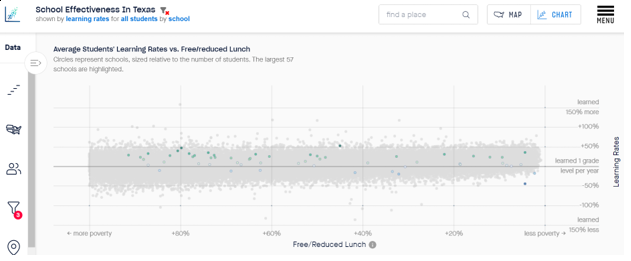

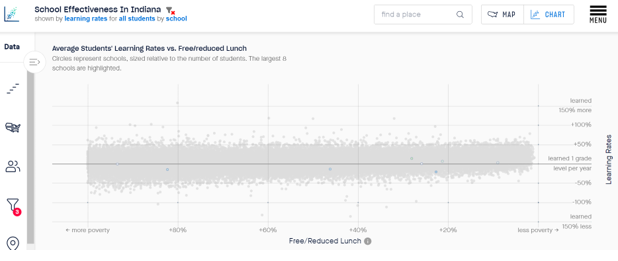

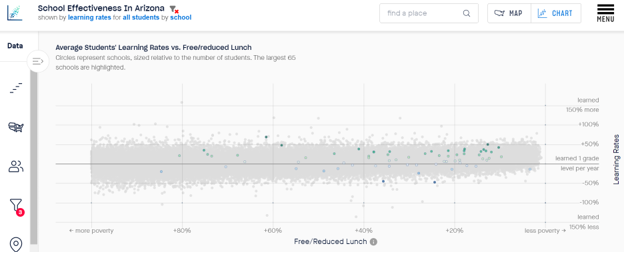

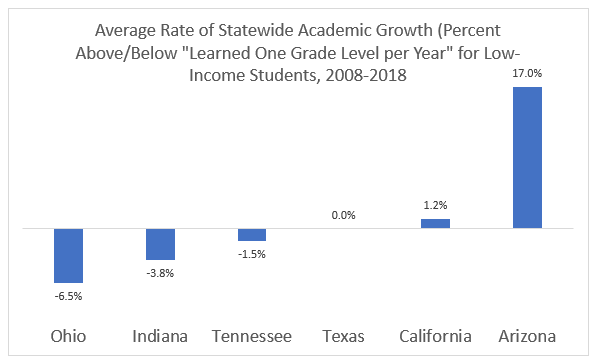

We can use the Stanford Educational Opportunity Project to visualize this, which allows us to select only charter schools by state (all the figures below). The project displays a variety of metrics, but we are using academic growth, which is broadly recognized as the best measure of school quality; each dot is a school, dots below the central “leaned 1 grade level per year” have below average growth.

The green dots have above-average growth. Furthermore, by pressing another button, all the charts below will be showing charter schools located in suburbs.

Why only suburbs? One of the main ways charter schools can help state K-12 sectors in your author’s mad-scientist mind is when charter schools to help states to avoid this:

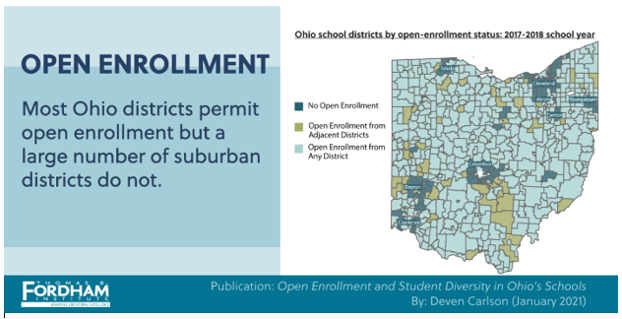

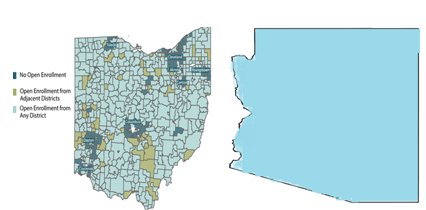

This is a school district map of Ohio showing every urban district in the state either completely surrounded or else mostly surrounded by districts that do not participate in open enrollment. Why do Ohio districts avoid open enrollment? Well because they can:

If you squint, you can find one charter schools to the right of the 40% Free and Reduced Lunch line. Fancy Ohio school districts, in other words, were almost perfectly safe from charter school competition. Ohio charter schools did almost nothing to get them to participate in open enrollment, which is why Ohio lawmakers removed geographic restrictions on charter schools and passed new private choice programs a couple of sessions ago.

Next up would be a state that is more of a work in progress: Texas. Texas has no statewide policy on open enrollment, and it really has yet to take off. If Texas had more charter schools in the suburban areas, it might get an open-enrollment virtuous cycle going, especially if Texas lawmakers would also pass private school choice.

Needs more work, and private school choice would help, but further along than Ohio toward getting a geographically and economically inclusive sector of the sort that will encourage open-enrollment to flourish.

Texas suburban charters are delightfully green from a performance standpoint, but not yet numerous enough to put a chill in the spine of Plano ISD. Let’s call it “getting there.”

Here is one of the larger state charter sectors for a charter law passed since the year 2000: Tennessee.

There are some very high growth charter schools in Tennessee, which is great, but they have zero suburban charter schools, which is not great. If you are looking for a charter sector that leaves suburban districts as walled-off fortresses, alas, Tennessee has a how-to manual charter statute. Tennessee has out-Ohioed pre-reform Ohio itself.

Ironically, California can show Tennessee how to do it:

California is the nation’s largest state with the largest K-12 population. I’m uncertain as to whether the California suburban charter school sector was large enough to encourage an open-enrollment revolution, but they were certainly trying.

The California suburban charter sector is large and green. Unfortunately, it is also politically hamstrung and contained. While there is no prospect for private choice programs in California, lots of Californians seem to be yomping their K-12 on their own-definitely something to keep an eye on.

Open enrollment may have begun to stir to life in Indiana, but it isn’t getting much help from the charter sector:

Luckily, Indiana has a robust private choice system which lawmakers just made stronger.

Arizona lawmakers passed both charter school and statewide open enrollment legislation in 1994 and the first scholarship tax credit program in 1997. Lawmakers expanded the tax credit in several different ways before passing the first Education Savings Account program in 2011, which was made universal in 2022.

Arizona has the nation’s largest charter school sector at 22% of public-school students, and the suburban charter school sector looks like:

Arizona doesn’t have the size of the California suburban charter sector, but it is a much smaller state, which may be why my (very) homemade equivalent to the Fordham open enrollment map for Arizona looks like:

Which might have something to do with:

It’s best to turn the choice knob all the way to “11.”

|

Tabernacle Christian School in Hickory, North Carolina, one of 844 private schools in the state serving more than 13,000 students, teaches all subjects from a biblical worldview and encourages social development through the teaching of good manners, high moral standards, respect for parents and authority, and patriotism. All teachers at the K-12 school are Christians who serve at their local church.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Friday on the centersquare.com.

With an estimated 77,000 on charter school waiting lists, lawmakers in the North Carolina House of Representatives on Tuesday will consider several bills designed to open up school choice for families.

The House Education Committee will hear three bills that could provide more school options for North Carolina families: one to expand Opportunity Scholarships, another to streamline charter school approvals, and a third to allow open enrollment in public schools.

House Bill 823, known as Choose Your School, Choose Your Future, is sponsored by top House Republicans including Speaker Tim Moore, R-Cleveland, to expand Opportunity Scholarships to all students through a tier-based system based on income.

The program is currently restricted to low- and moderate-income families to cover private school tuition and other educational expenses. Parents for Educational Freedom President Mike Long contends the expansion would mark “an incredible step toward funding students over systems in North Carolina,” while the state’s teachers association is lobbying against the bill.

The program currently helps more than 25,000 students attend 544 private schools.

The committee will also review House Bill 618, to create a Charter School Review Board to take over responsibility for approving, amending, renewing and terminating charter schools. It would reshuffle the authority of the State Board of Education; the legislation is aimed at streamlining the process, though the state board would retain oversight over the review board.

To continue reading, click here.

North Hollywood High School Zoo Magnet in North Hollywood, Calif., is the 2023-23 recipient of Magnet Schools of America’s Dr. Ronald P. Simpson Merit Award of Excellence. The school is recognized by the American Association of Zookeepers as one of six high schools in the nation partnered with a working zoo.

Magnet Schools of America, a national nonprofit education association that represents more than 4,340 magnet schools serving nearly 3.5 million students across 46 states and the District of Columbia, named two Florida educators as awards recipients at the 2022-23 National Conference on Magnet Schools.

Pasco County Schools superintendent Kurt S. Browning is the association’s School District Superintendent of the Year. Browning has been the driving force behind an education choice transformation in the district, implementing innovative magnet programs at all grade levels.

The group praised Browning for providing the appropriate support to ensure quality, equity, and success for the district’s magnet programs.

The association’s website notes that leadership, commitment, and involvement are the three descriptors that capture the essence of what the group seeks in candidates for MSA Superintendent of the Year. Eligible candidates must have served as superintendent within the district in which they are being nominated for two years; must be a member of Magnet Schools of America at the time of nomination; and must include a letter of nomination in their application packet.

The organization named Daniel Mateo, an assistant superintendent for Miami-Dade County Public Schools, National Magnet School District Administrator of the Year. The group praised Mateo for his deep understanding of the unique needs and challenges of magnetMSA, a national nonprofit professional education association whose members are schools and school districts.

Nominees for Administrator of the Year must embody leadership, support and community. They must have served as a district level magnet administrator for a minimum of two years and be an active member of Magnet Schools of America at the time of nomination.

“These awards are a significant achievement for all magnet schools,” said Ramin Taheri, CEO for Magnet Schools of America. “All of our award recipients competed with a large number of schools and individuals. We are honored to have acknowledged their great work.”

Other 2022-23 award recipients include:

Editor’s note: This article appeared last week on the Thomas B. Fordham Institute’s website.

Editor’s note: This article appeared last week on the Thomas B. Fordham Institute’s website.

A little-noticed event in late 2022 destabilized a pillar of contemporary American K–12 education, namely that all schools considered part of the public system must be secular.

Last December, the attorney general of Oklahoma issued an advisory opinion stating that, due to recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions, the state could no longer prohibit faith-based groups from operating charter schools. Catholic leaders seized the opportunity and applied to do just that; the state’s virtual charter board voted down their application this week, but delayed a final decision until a revised application is submitted.

Not long after, in Arizona, one of the nation’s most successful charter operators announced it was launching an initiative to start faith-based classical schools. Though technically part of the private-school sector, these schools would be based on the organization’s charter-school model and would access public funding available via a new state Education Savings Account program that gives education dollars directly to families.

Though the efforts are distinct – the Arizona case brings faith-based education and public schooling closer, while the Oklahoma case merges them – they are, in a sense, the logical conclusion of thirty years of choice-based reform. Backers and detractors, however, see “logical conclusion” very differently.

Opponents might say they suspected choice advocates were fighting from day one to raze the wall separating church and state. Proponents might say this is an obvious, sensible consequence of American pluralism: Given the nation’s long history of faith-based nonprofits, once government engaged civil society in school operations via chartering, it was inevitable that religious groups would want to participate.

Like so much today, this issue divides observers along political lines. Indeed, the idea deeply troubles many progressives. But those on the political left might consider whether they could support faith-based charters, even if just as a pilot program.

Part of this consideration should be strictly pragmatic, as it pertains to keeping families engaged with the public school system. Opinion on public education is souring, with Americans now giving lower grades to schools both locally and nationally than before the pandemic. Today, only about one in five give the nation’s schools an A or B; only 21% of non-parents think American K–12 education is headed in the right direction.

A 2022 Gallup poll revealed that public satisfaction with K–12 schools was at its lowest level in more than 20 years.

To continue reading, click here.

Recently, I had the opportunity to speak to a group of state lawmakers, one of whom asked me a startling question after acknowledging that his state doesn’t have charter schools: Should we really bother with them?

Recently, I had the opportunity to speak to a group of state lawmakers, one of whom asked me a startling question after acknowledging that his state doesn’t have charter schools: Should we really bother with them?

As I heard the record scratch in my head, my mind wandered to a documentary I saw about the Wrecking Crew, a very busy group of studio musicians in Los Angeles in 1960s. Come along for the ride, it will all make sense in the end.

While often uncredited, the Wrecking Crew played on scores of hit records while the credited artists would sometimes tour only to play simpler versions of the songs with their lesser musical talent. The Wrecking Crew played instruments on the Monkees’ first two albums.

Watching the 2008 documentary, it occurred to me that the Wrecking Crew likely was a big reason that pop-music from the 1960s has a distinctive sound. Much of the memorable music was in fact recorded by the same musicians.

The charter school movement also had a wrecking crew, but unlike the musical version, the charter wrecking crew has had a negative impact.

I’ve always been, and remain, an “all of the above” choice type of guy. Open enrollment, homeschooling, private choice or charter schools? Yes please! On the other hand, I’ve been aware that many, many years have passed since someone passed a robust charter school law.

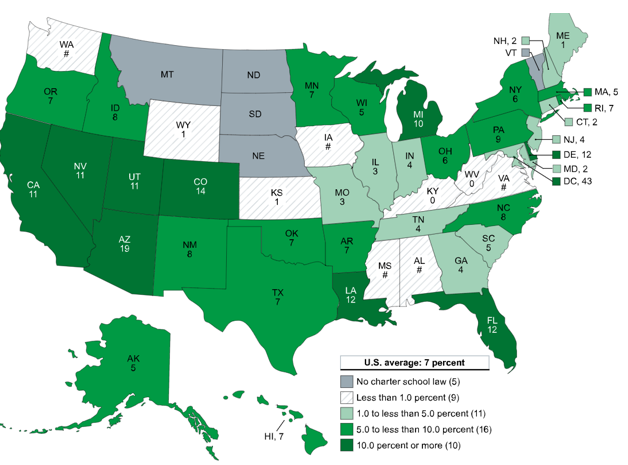

To illustrate the point, there are nine states on this 2019 map from the National Center for Education Statistics that had fewer than 1% of students enrolled in charter schools. West Virginia passed its law in 2021, so let’s give it a pass for now.

As for the remaining states, Alabama passed a charter law in 2015 and has five charter schools. Kansas passed a charter law in 1994 and has nine charter schools. Kentucky passed a charter law in 2017 and has zero charter schools.

Iowa passed a charter law in 2002 and has two charter schools. Mississippi passed a charter law in 2010 and has seven charter schools. Virginia passed a charter school law in 1998 and has seven charter schools. Washington passed their law in 2016 and has twelve charter schools.

The best charter laws passed since 2000 are in Indiana and Tennessee. Both had a less-than-stellar 4% market share in 2019.

Color me skeptical about the prospects for some of these states of reaching a double-digit charter market share before Haley’s Comet reappears in 2061.While there are some real stinker charter laws that passed before 2000, the malodorous consistency since 2000 is disappointing.

So again, imagine the Wrecking Crew, but in your imagination band members are confused about how to play their instruments. The songs sound similar, but they all sound bad. You know, like Nickelback.

I believe I answered the question from the lawmaker by saying that creating charter schools is a purely local decision. But then I got to thinking: What if during the early stages of COVID-19 someone had the bright idea of having states set up commissions to judge the worthiness of pandemic pods before they would be allowed to operate? Submit an 800-page application, hire the right consultants, and dig in for a multi-year process as the judges subject you to a technocratic beauty pageant.

People used to like all kinds of weird and antiquated things, but American parents are way past taking whatever commissions choose to give them. Choice advocates should catch up with parents – and consider partying like it’s 1999.

Otherwise, the movement in many states will remain wrecked.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Tuesday on postandcourier.com.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Tuesday on postandcourier.com.

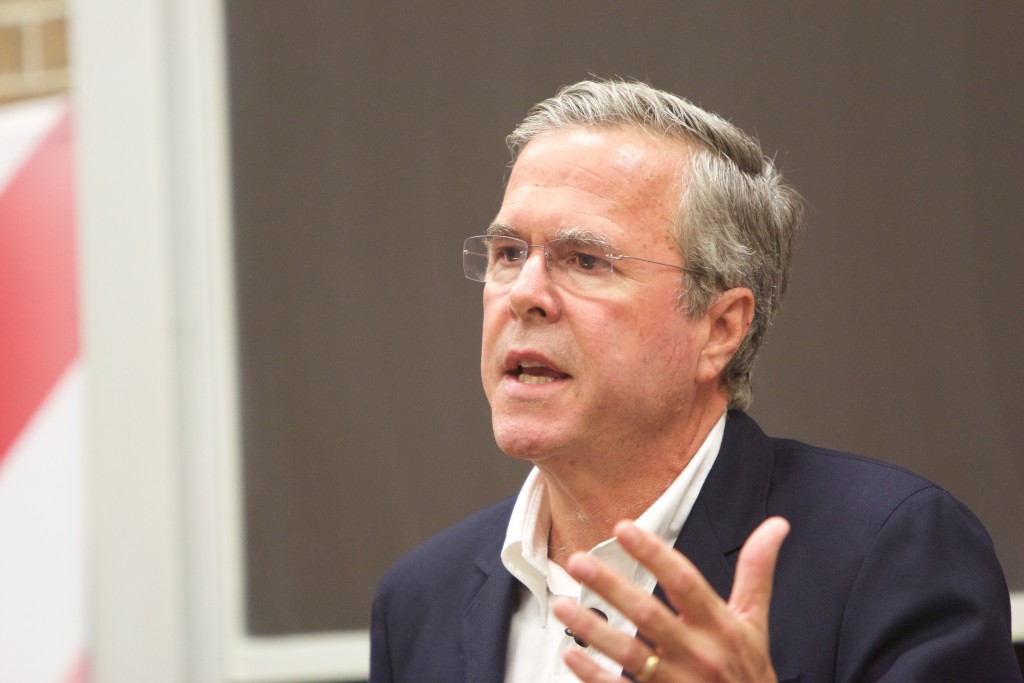

Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush gave Republicans in the South Carolina House a pro-school-choice pep talk ahead of a public hearing on legislation that would give parents money for private tuition.

Bush, who signed Florida’s first school choice law nearly 25 years ago, encouraged the House GOP Caucus to charge ahead with efforts to give parents taxpayer-funded choices in both public and private schools.

“I want to maybe give you a sense of what the future looks like,” Bush told the caucus during an April 4 luncheon that was open to the media.

“The world gets better when parents make more choices,” he added. “There are lessons on the way to make sure it’s done right, but the idea parents know best for their kids is irrefutable in my mind.”

Chairman of the nonprofit ExcelinEd, Bush said he was in South Carolina this week before Easter as an evangelist for school choice.

It was a pitch that seemed to preach to the choir.

Republicans in the House have been pushing for private school choice for nearly two decades. After years of dividing the GOP, legislation helping parents pay for private school almost reached Gov. Henry McMaster’s desk last year. It failed at the end of the session with Republicans in the House and Senate unable to agree on student testing.

To continue reading, click here.

Cole Valley Christian Schools in Meridian and Boise, Idaho, one of 157 private schools in the state, infuses scripture into every subject, not just Bible class, and gives children the opportunity to connect with God outside of daily classwork.

Editor’s note: This news release appeared Wednesday on yes. every kid. website.

In response to Gov. Brad Little’s signature of Senate Bill 1125 expanding public school access by ending discrimination against students based on their ZIP code, an advocacy group with a families-first approach to expanding the country’s education policy landscape, had this to say:

“Access to a great school should not be determined by a family’s income or where they live,” said Craig Hulse, executive director of yes. every kid. “With Gov. Little’s leadership and bipartisan support from the Idaho Legislature, the state has taken critical steps toward creating a truly student-centered education experience by opening up public schools so a student is no longer limited by ZIP code and can access more educational options.

“This is a much-needed opportunity to modernize learning and streamline the ability for children to attend a school that meets their individual needs.

“We thank Gov. Little, Sen. Lori Den Hartog, and Rep. Wendy Horman for their unwavering commitment to Idaho families and look forward to working together to continue advancing public policy that respects the dignity of every kid.”

Idaho’s Senate Bill 1125 passed with overwhelming bipartisan support, reflecting families’ growing desire for more opportunities other than the district school they are assigned to attend.

SB 1125 rewrites the state’s open enrollment law for the first time in three decades, removing barriers that prevented students from accessing the right school that’s best for them. The law will:

Now signed into law, SB 1125 cements Idaho’s status as a national leader in ending school zoning discrimination.

The Master’s Academy football program seeks to improve players’ God-given talents, teach them how to be team players, and learn valuable life skills through the sport of football.

While transformational bills to expand education choice eligibility have taken center stage during the Florida legislative session, other measures that would affect those already participating in choice programs also are under consideration.

Some may not make it to the finish line before the end of the eight-week session, but at least one measure is already on track for approval.

Companion bills HB 225 and SB 190 would allow charter school students to play on private school sports teams and participate in private school extra-curricular activities. Current law already allows homeschooled students to do this, and these bills would extend the same provisions to those who attend charter schools.

A recently approved amendment in the House Choice and Innovation Subcommittee also extended the provision to students enrolled in Florida Virtual School.

Under current law, if a specific program isn’t available at a charter school, the only option for those students is to sign up for it at their zoned district schools. The proposed legislation would let charter students choose between the district school and or a nearby private school through a special agreement.

SB 190 is set to be heard on the Senate floor starting at 1:30 p.m. Thursday; HB 225 won final approval in that chamber on Friday and was sent to the Senate, where it is now in the Senate Rules Committee.

The bills were inspired by an incident last year in Vero Beach, in which a group of charter school students were forced off the Master’s Academy varsity football team in the middle of the season of their senior year after someone complained.

The arrangement had been going on for years based on an interpretation of the law allowing homeschoolers to play for private schools. The Sunshine State Athletic Conference also overturned all of Master’s Academy’s victories at that point, though the private school ended up winning the championship.

“We were heartbroken,” Wayne Smith, the head of schools at Master’s Academy, told Florida Politics in January. “It hurt us, but more than that, it hurt these charter school boys who had nowhere else to play, nowhere else to go, and suddenly they were without a team — kicked off a winning team, nonetheless.”

Smith, whose school has 45 high school students, said the charter students would be unlikely to make the team at their district high schools, “So, they come to us.”

State Sen. Erin Grall, a Republican whose district includes Vero Beach, sponsored SB 190 and said the legislation would create consistency among all students who participate in different forms of education choice.

“The parent makes the decision not to send their child to the public school they’re zoned for and instead chooses to send their child to a charter school,” she said. “This lines up the homeschooling statute with the charter school statute … to fix it and make it more clear.”

Editor’s note: Pondiscio is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where he focuses on K–12 education, curriculum, teaching, school choice, and charter schooling. This commentary, published here in its entirety, first appeared on nationalaffairs.com.

Editor’s note: Pondiscio is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where he focuses on K–12 education, curriculum, teaching, school choice, and charter schooling. This commentary, published here in its entirety, first appeared on nationalaffairs.com.

There's a story often told about Ronald Reagan who, in 1980, hired Lionel Sosa, a San Antonio advertising executive, to help court the Latino vote for his presidential campaign. Reagan reportedly told Sosa his job wouldn't be difficult. "Latinos are Republican," he observed. "They just don't know it yet."

The remark reflected the small-c conservatism of Latino voters, whom Reagan often praised. At a 1982 White House event celebrating Hispanic Heritage Week, for example, Reagan described the community as "bound by strong ties of language, religion, family, and culture...that enrich America and keep us strong and free." Forty years later Reagan has proved prescient, as Latino voters have begun to drift rightward in recent election cycles.

A similar, if less intuitive, case can be made today about public-school teachers, who preside over one of the most crucial institutions in forming the attitudes, beliefs, and character of the nation's children. Only in this instance, Reagan's remark might be better rendered in reverse: Public schools and teachers are by their very nature, conservative; it's conservatives who just don't know it yet.

If this argument falls flat at first blush, it's because the political right has long conditioned itself to regard public education as broken beyond salvation. At the same time, public-school teachers, or at least their unions, have for decades borne the full brunt of criticism from conservatives and the broader education-reform movement — and not without reason.

Teachers' unions have reliably resisted any attempts at meaningful change, often protecting the interests of teachers at the expense of students. Stanford political scientist Terry Moe — whose 1990 book Politics, Markets, and America's Schools, co-authored with John Chubb, is widely regarded as the urtext of the modern education-reform movement — has described the failure of the decades-long reform effort as "largely due to the power of the teachers' unions."

For its part, the Republican Party has traditionally been anti-union, regarding public-sector unions in particular as bolstering electoral prospects for Democrats.

If teachers' unions have been fitted for black hats by their critics, they've often seemed inclined to wear them with glee. Albert Shanker, president of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) from 1974 to 1997, is said to have insisted that he represented teachers, not children (though he believed their interests were aligned).

AFT's current president, Randi Weingarten, emerged as one of the highest profile (and most controversial) figures during the Covid-19 pandemic, pressuring public-health officials behind the scenes to keep schools closed while publicly insisting she was working to reopen them, and generally appearing indifferent to the learning-loss potential of disrupted school schedules and routines.

Conservatives commonly complain that public education has been captured by progressive ideology. But in many respects, education is inherently progressive. When it succeeds, it is an engine of social advancement, fairness, and upward mobility — all goals broadly aligned with the outlook of multi-racial, working-class progressivism.

At the same time, a school is an inherently conservative institution. We build and maintain schools to expose children to our nation's history and culture, and to prepare them for a responsible adult life of informed, engaged citizenship. While teachers might not think of themselves as conservative, they staff institutions that have proved remarkably resistant to change.

Public schools endure in their basic form and function not because we lack alternatives to placing two dozen children in a classroom led by an adult every weekday, but because sending children to a place called "school" is an enduring and valued cultural habit in nearly every American community. Thus there lies a paradox at the heart of our relationship with public education: In the long run education serves progressive ends, but those ends are accomplished through conservative institutions.

In recent decades, left-leaning education activists have pushed too hard on the progressive side of the equation, causing trust in public schools among conservatives to plummet. In turn, many conservatives have escalated their attack on public education — and public-school teachers in particular — while calling for parents to abandon local public schools in favor of alternatives like charters, private schools, and homeschooling.

School choice is a necessary corrective to the well-documented failures of many public schools. At the same time, conservatives should think long and hard before retreating from engagement with traditional public education. The problems with American public schools are legion, but a simple fact dwarfs all others: They are where the children are.

Origins of antagonism

The roots of conservative antipathy toward public education stretch back more than a century, to an era of intense social and political reforms.

In his 2010 book Saving Schools, Harvard political-science professor Paul Peterson described how early in the 20th century, an "articulate class of educated middle-class professionals — an intelligentsia, as it were — was gathering strength in politics, journalism, the universities, and the professions." "It was only a matter of time," he concluded, "before schools would capture their attention."

These intellectuals became increasingly enamored with progressive pedagogical ideas championed by education theorist John Dewey, who believed that education was "the fundamental method of social progress and reform."

"Few reform movements have been as successful at changing the educational system's structure of power," Peterson observed. "The progressives were so effective, in fact, that eventually it became quite unclear whether the schools belonged to the public or to the professionals." Echoes of this critique still resonate with the public today.

Among the more visible effects of progressive reforms was the consolidation and centralization of public-school districts, reducing their number from 120,000 to about 14,000 nationwide. Reformers also pushed school-board elections from November to other parts of the year, depressing voter turnout and placing even more control in the hands of the most engaged and invested citizens — particularly teachers and their unions. In Peterson's telling, progressive ideas congealed into a set of professional interests, further weakening local control of schools. Questions soon began to gnaw at the conservative mind:

"Were the professionals really as public-spirited, politically disinterested, and scientifically grounded as they claimed? Were the schools of education, now in control of the paths to teaching, counseling, and administration, capable of turning out a talented workforce?"

Closer to our own time, doubts about the quality of American public schools and their teachers reached a full boil with "A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform." Published in 1983, the report raised troubling questions about public education's capacity to produce a competitive workforce, famously asserting that "[i]f an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war."

The report drew intense criticism and rebuttals, but it instilled the message of education's decline in the nation's consciousness and would inform federal K-12 policies for decades to come.

Around the same time, the public image of the teaching profession reached its nadir — and not just among conservatives. At the start of the 21st century, Democrats, typically reliable union allies, joined forces with George W. Bush's administration to enact No Child Left Behind. The statute significantly changed the climate of nearly every classroom across America, mandating annual tests in reading and math for almost all students in grades three through eight.

At the same time, an emerging and youthful education-reform movement was bristling with do-gooder energy and optimism — much of which was directed at ousting poorly performing teachers. Time magazine put Washington, D.C., schools chancellor Michelle Rhee on its cover wielding a broom, symbolizing her intention to sweep poor performers out of the city's classrooms.

Newsweek soon followed suit with a cover story insisting that the fix for American education was simply to "Fire Bad Teachers." In her 2014 book The Teacher Wars, New York Times education reporter Dana Goldstein noted that the pro-reform movie Waiting for Superman "portrayed all urban neighborhood public schools as blighted places packed with incompetent tenured teachers, while presenting nonunionized charters as the solution."

Elite college graduates, hoping to fill the gap in high-quality teachers at public schools, applied in record numbers to Teach for America, which trained them to teach students in impoverished schools.

As bipartisan enthusiasm for reform waned in the 2010s (in large part due to its failure to generate results, which Chester Finn and Frederick Hess have outlined in these pages), conservatives coalesced around school choice as their preferred lever for change. The thinking was that with more options available, public schools would have to compete for students by providing more attractive curricula, programs, and facilities. Conservatives continue to champion school choice to this day.

Curiously, there was — and continues to be — a decidedly anti-conservative cast to the education-reform movement of the last few decades. Disruption doesn't come naturally to conservatives, who are generally more inclined to prize the stability of institutions than to seek to disrupt or dismantle them.

Moreover, there is an unmistakably technocratic flavor to an approach that imposes academic standards, accountability, and standardized testing from the top down to jolt American K-12 education from decades of complacency and desultory results. In that sense, the education-reform movement is an echo of the Progressive-era reforms that put off conservatives in the first place.

At the same time, conservatives' reverence for custom, convention, and continuity are more complicated when those institutions are government-run. This has become increasingly apparent in recent years.

Writing for this journal in 2014, Peter Wehner and Michael Gerson described an "anti-government fervor" that was escalating in both its intensity and appeal on the American right. A skeptical view of government is nothing new among conservatives, particularly those with more libertarian convictions. But the pair took prescient note of a "rhetorical zeal and indiscipline in which virtually every reference to government is negative, disparaging, and denigrating."

The fervor they described would soon reach a tipping point, beginning in the spring of 2020.

Pandemic disruption

The Covid-19 pandemic significantly altered the relationship between public schools and their many stakeholders — especially parents. Unpredictable schedules, masking restrictions, frequent forced absences due to quarantine rules, and discontent with remote learning contributed to an unprecedented student exodus: As the 2022-2023 school year commenced, approximately 1.2 million students had exited public-school districts nationwide since the lockdowns began.

The longer schools operated under a threat of closure, the more likely parents were to have made alternative plans for their children's education. Nationally, home-school enrollment jumped from 2.8% of students in 2019 to 5.4% in 2021. Public charter schools added 240,000 students to their rolls.

Between 2020 and 2021, private schools — which were more likely to offer in-person instruction than their public counterparts — saw their enrollment swell by a staggering 19%, or an extra 1 million students. Even after the pandemic subsided and in-person schooling resumed, alternatives to traditional public schools had become part of many families' established routines.

At the same time, culture-war issues further exacerbated tensions between parents and school boards. Fights in many school districts over masking policies, critical race theory, gender ideology, book bans, and other hot-button social issues became commonplace in schools more accustomed to serving as community hubs than as ideological battlegrounds.

Hanging over all of this was the now indisputable evidence of profound student learning loss that occurred over the course of the pandemic. The latest round of test scores released last year from the National Assessment of Educational Progress — often referred to as the nation's report card — saw dramatic declines in reading and math scores for students in most states.

Each of these factors, separately or in combination, has had a deleterious effect on Americans' already complicated relationship with teachers and public schools. For decades, an annual Gallup survey measuring views of the honesty and ethics in various professions has shown teachers to be among the most trusted occupations in the country.

Before 2020, 75% of Americans agreed that grade-school teachers have high "honesty and ethical standards." A year later, that number had dropped to 64% — still among the highest scores relative to other occupations listed in the survey, but an all-time low for the profession and moving closer to the ambivalent sentiments the public has long attached to public education at large.

(Americans have seldom held public education in high regard, but local schools and their own children's teachers have historically tended to be exempt from such harsh judgment.) A separate Gallup survey found that only 42% of Americans say they are satisfied with U.S education — the lowest level in two decades, and the second-lowest rating recorded in the poll's history.

Today, few Americans are content with their children's education. In recent election cycles, Republican candidates for state and local office have seized on the moment by challenging the curricula and culture of public schools on ideological grounds. Many of them have positioned themselves as champions of parents, insisting that families must have a say not only in what is taught, but in who makes fundamental decisions in directing their children's education.

This has led to renewed calls among conservatives to expand school choice, which is on the march nationwide. As of this writing, five states — Arizona, West Virginia, Iowa, Utah, and Arkansas — have adopted laws creating universal "education savings accounts," which give nearly all parents in those states the ability to opt out of district-run schools and command the use of state dollars to direct their children's education themselves.

School choice is not enough

It's not entirely surprising that conservatives would see school choice as the best defense against a public-school establishment that seems unable to improve and hostile to conservative values. Breaking the monopoly of public education forces schools to compete for students and funding, spurring innovation and excellence in turn.

At the same time, favoring school choice as the exclusive, or even primary, lever of reform while disengaging from efforts to improve public education would be a mistake for several reasons.

For starters, asking America's parents to abandon their support for local public schools in favor of entirely new educational paradigms is a heavy lift. Changing schools or opting to home school can be profoundly disruptive to family life and routines, as well as children's social lives.

Transportation challenges are often insurmountable. If the majority of American families seem stubbornly attached to local public schools, it can't be explained away by a lack of parental engagement or credible alternatives; it's often the result of more practical considerations.

Neither is school choice the bulwark against progressive indoctrination that proponents paint it as. At elite private schools serving families with the most resources and the greatest number of schooling options available to them, the cutthroat competition for seats, combined with social pressure to be "anti-racist," has made those schools more inclined to adopt progressive policies and curricula. For a range of reasons, many private-school parents have shown an unwillingness to buck their schools' strident progressive orthodoxies.

More fundamentally, though, arguments for choice as the main solution to failing public schools sidestep the shared interest Americans have in public education. Parents of school-age children undoubtedly have the most personal stake in the quality of schools available to them, but the claim that families should have control over "their" money elides the fact that the cost of education in the United States is socialized:

We pay school taxes regardless of whether we send our children to public schools, or even whether we have children at all. Choice strategies like vouchers, education savings accounts, and other such mechanisms, therefore, put parents in control of our money.

It makes sense to put decision-making in the hands of those closest to schools and with the most at stake — namely their own children. But the shared cost implies a mutual interest, as well as a literal investment in every child. School choice can solve a school-based problem for a family, but it can't address the interest every American holds in the education of the next generation.

None of this is to suggest that conservatives should abandon the push for school choice. The clearest triumph of the reform era has been the creation of new education institutions — particularly public charter schools, which are largely free from unionization and bureaucratic meddling. New networks of high-performing urban charter schools in particular have provided critical relief to communities beset by generations of public-school failure.

School choice is a positive force for education pluralism and system-wide improvements, and conservatives should continue encouraging and supporting choice-oriented reforms.

School choice can be many things — a safety valve for parents unsatisfied with local district schools, a way for schools with new curricular models to emerge, and a strategy for injecting competition and dynamism into K-12 education. What school choice is unlikely to provide anytime soon, if ever, is a replacement for the nearly 14,000 government-funded school districts in America and the 100,000 schools they run.

As of the fall of 2019, more than 90% of America's school-age children attended schools run by public-school districts. While those numbers have fallen post-pandemic and are unlikely to return to their earlier level, only about 2.6% of students left public schools between 2019 and 2021.

The inescapable truth about education in America is that there is no foreseeable scenario under which traditional public schools will not educate the majority of the nation's future entrepreneurs, engineers, doctors, soldiers, and citizens for generations to come. Conservatives are not wrong to take exception when activists seek to impose a progressive agenda on what is at heart a bedrock government service, but their response of promoting school choice as a conflict-avoidance strategy functionally cedes public education — and the vast majority of America's schoolchildren — to the left.

If conservatives earnestly believe that public education is a hotbed of progressive indoctrination on social and political issues, it would be an act of self-immolation to surrender future generations to its influence.

The failure of public schools to cultivate values and character traits congenial to conservatives is not an argument for disengagement any more than the breakdown of family structures or a high divorce rate delegitimizes family life. The appropriate response in both cases is not to abandon the institution, but to recommit to strengthening it.

On that front, conservatives will need allies. Their most promising potential partners could come from an unlikely group: public-school teachers.

Common ground

Conservatives have long criticized teachers for their progressive ideological leanings. Yet most public-school teachers are less hostile to conservative views than is commonly assumed. In 2017, Education Week commissioned a nationally representative survey of teachers on their political views. Only 5% of teachers described themselves as "very liberal," while another 24% described themselves as "liberal." A plurality (43%) described themselves as "moderate."

The remaining 27% identified either as "conservative" or "very conservative" (roughly the same number as those who identify as "liberal" or "very liberal"). This would make the teacher workforce only slightly less conservative, and somewhat more moderate, than Americans at large.

This should come as no surprise. There are over 3 million teachers in public-school classrooms — a number so large that it would be hard for the group to differ dramatically in its political positions from those of the population as a whole. Debates over education, however, tend to be driven by union leaders, political advocates, faculty at colleges of education, and philanthropic funders, all of whom are a deeper shade of blue than the teachers they represent or seek to influence.

Conservatives would do well to look past the rhetoric of these actors and focus instead on teachers themselves. If they do, they might be surprised to find allies among public-school teachers on any number of issues.

One fruitful source of the common ground may be student behavior, which has emerged as one of the most significant factors driving teachers from the profession. During the 2021-2022 school year, one in 10 teachers reported being physically assaulted by students, while 43% said at least one colleague was attacked in their district.

Meanwhile, half of the National Education Association's teachers say they'll retire or leave the profession sooner than they'd planned, with 76% citing student behavior as a serious issue in their classrooms. Conservatives, already skeptical of trends like restorative justice and impatient with lax student discipline, are likely to find supporters among teachers who demand safe and orderly classrooms.

There is also a demand among teachers for common-sense, measured curricular policies that appeal to conservative pragmatism. The push for equity in schools across the country, to take one example, has led some administrators to make curricular decisions that will likely hurt the students they seek to help.

In 2022, for instance, the Virginia Department of Education's Mathematics Pathways Initiative proposed "de-tracking" math classes for the state's students through 10th grade on the theory that tracking has a disproportionately negative impact on lower-income and minority students. In effect, students of all academic abilities would take the same math classes.

Predictably, the loudest outcry against this measure and others like it came from the right. But a nationally representative survey of teachers also found that only 10% thought this would be a good idea. Their reasoning is not hard to understand: It is exceedingly difficult to write and execute lesson plans that challenge the most advanced students while ensuring that students who struggle in the subject aren't being left behind.

Without additional support, lumping together students of multiple abilities in a single classroom makes it harder for teachers to teach and, in turn, for students to learn.

There is even potential for consensus among conservatives and teachers on teacher pay. Dozens of models exist for raising teacher salaries that would appeal to those on the right, one of which involves giving teachers the opportunity to increase their pay based on performance. The IMPACTplus pay schedule in Washington, D.C.'s public schools offers an example: Highly effective teachers in schools with a high concentration of poverty can increase their salaries to as much as $130,000 per year.

Less expensive models provide better compensation while staying within school budgets by managing teacher workloads creatively; such strategies can boost pay by more than 40%. In March 2022, Florida governor Ron DeSantis, a likely Republican candidate for president in 2024, announced that all teachers in the state would receive a raise, bringing the average starting salary for a Florida teacher to $47,000 — a $7,000 increase compared to the 2020 average.

"It's just something I think is really, really important," he said of the measure. "We do appreciate the folks who are working with these kids, particularly during [the pandemic]." DeSantis's decision, coupled with the continued support he receives from conservatives, shows that increasing pay for public-school teachers is not a third rail for voters on the right.

Even on the most ideologically tinged arguments surrounding schools, there is room for compromise. In recent years, legislatures have passed curriculum restrictions on critical race theory in 17 states. Yet 74% of self-described moderate teachers and 57% of conservative teachers oppose such bans. With regard to bans on gender and sexuality curricula, 65% of moderate teachers and 49% of conservative teachers oppose them.

It's not surprising that teachers would prefer to facilitate conversations on sensitive subjects with students as opposed to being banned from mentioning them. But polls indicate that parents also want controversial topics discussed in school — particularly at the high-school level — as well. The discomfort comes into play with the perception that schools are preaching, not teaching.

This suggests an opportunity for conservatives and teachers to coalesce around teacher codes of conduct aimed at ensuring viewpoint diversity in classrooms with a fair, community-deliberated consensus on how challenging discussions are to be framed.

Realignment?

Public-school teachers preside over critical institutions responsible for the education and character formation of the vast majority of the nation's young people. Yet in recent years, those institutions have drifted from the purpose of preparing children for productive adult life and engaged citizenship, causing a dangerous decline in parents' trust of public education.

Interestingly, mistrust runs in both directions: A 2018 poll conducted for EdChoice showed that only about a third of teachers (36%) say they trust parents — a level below teachers' confidence in their principals, union leadership, and district superintendents.

If teachers in our nation's public schools wish to restore Americans' trust in education — which enables them to continue serving as teachers — they must be willing to acknowledge a simple fact about their profession: They're not free agents, but government employees with enormous influence over a captive audience of other people's children.

If teachers begin to see themselves not as independent actors or activists, but as self-conscious stewards of a crucial public institution, they might be surprised to find allies among conservatives on any number of issues that are key to their job satisfaction.

At the same time, conservatives would do well to cease fomenting parental discontent with public schools to advance prospects for school choice. Discontent breeds mistrust on both sides, and the less teachers trust American parents, the more willing many will be to take it upon themselves to reeducate their children — often with progressive principles in mind.

Expanding school choice may be a worthwhile pursuit, but the fact remains that American parents overwhelmingly demonstrate a preference for local public schools. If conservatives cede public schools to the left, they will effectively abandon the vast majority of America's future generations to the progressive cause.

The opportunity exists and would likely be acceptable to a critical mass of both public-school personnel and conservatives, to renew trust in public education by restoring it to its proper role as a collection of local institutions operating in the public interest to prepare American children for the challenges of citizenship and adult life.

This is certainly a more modest role than the activist mentality embraced by some, but by no means all, of the nation's 3 million public-school teachers. And yet it serves the interests of both teachers and conservatives — not to mention Americans more broadly.

Making common cause on public education requires both sides to acknowledge what is plainly observable: that schools are conservative (in the best sense) institutions that serve progressive (in the best sense) ends. Our fiercest arguments occur when either is encroached upon: When schools stray too far into progressive activism, or when education fails to deliver on its promise of being an engine of fairness and social mobility.

Reestablishing the proper balance between the two sides offers the critical first step toward restoring legitimacy and trust in this essential American institution.