Kentucky House Majority Whip Chad McCoy presented House Bill 9, which would make changes to the appeal process if a charter school application is denied by a local school board. Kentucky's Republican-led legislature authorized charter schools in 2017 but none have been created because lawmakers did not provide a permanent funding mechanism.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Tuesday in U.S. News & World Report

After years of inaction, charter schools would gain a foothold in Kentucky and be supplied with a permanent funding stream under a bill that won passage Tuesday in the state House.

The bill calling for initial charter school openings cleared the House on a 51-46 vote after a nearly three-hour debate, on the same day the measure barely emerged from a House committee.

Twenty-two Republican lawmakers aligned with Democrats to oppose the proposal, but the measure mustered enough support to advance to the Senate. Republicans have supermajorities in both chambers. Only a handful of days are left to pass the bill in time to ensure lawmakers could take up a promised veto by Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear.

The bill had a bumpy journey through the House, reflecting the hot-button status of charter schools in the Bluegrass State. The measure was removed from one House committee and reassigned to the Education Committee, which underwent a couple of last-minute membership changes before the crucial vote that helped push the bill through committee.

Opponents put up a spirited fight in the full House. During the long debate, Democratic Rep. Angie Hatton said: “You can cut the tension in this room with a knife today.”

Kentucky's Republican-led legislature authorized charter schools in 2017 but none have been created because lawmakers did not provide a permanent funding mechanism. The new measure would set up a long-term funding method for charter schools. Public charters, like traditional public schools, would receive a mix of local and state tax support.

To continue reading, click here.

Great Hearts Academy is the largest operator of classical charter schools in the U.S., with 33 schools serving 22,000 students in Arizona and Texas.

Editor’s note: This commentary about the largest operator of classical charter schools in the U.S. from Robert Pondiscio, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, appears in the Spring 2022 issue of Education Next.

Remote learning is hard to love. The nation’s forced experiment in online education the past few years has been a disaster for kids. Educators and parents alike have come to view virtual learning as a necessary evil at best, an ad hoc response to a national crisis.

In a survey by McKinsey & Company, 60% of teachers rated the effectiveness of remote learning between 1 and 3 out of 10. Many attribute remote learning to the catastrophic decline in academic outcomes and an alarming spike in mental health problems, with plummeting test scores and rising rates of depression and anxiety among students.

It’s also assumed to widen achievement gaps. The challenges of remote instruction “apply in affluent, English-speaking, two-parent households,” my colleague Rick Hess recently wrote. “Things get tougher still for single parents, families in tight quarters, or parents trying to communicate about all this in a second tongue.”

Online charter schools in particular had a poor reputation even before Covid, associated in many minds with low-rigor credit recovery, poor performance, and mediocre graduation rates. A recent Brookings study of virtual charter schools and online learning during Covid was particularly grim, concluding that “the impact of attending a virtual charter on student achievement is uniformly and profoundly negative.”

Given that bleak and unpromising landscape, an outlier may be emerging: The online version of Great Hearts Academies is proving to be both an academic standout and popular with families. That has officials at the Arizona-based charter school network quietly thinking about launching a low-cost, online, private-school model to bring classical education to anyone who wants it at a price point below—even far below—other options, including Catholic schools. It’s one of several initiatives Great Hearts is weighing to expand its offerings.

To continue reading, click here.

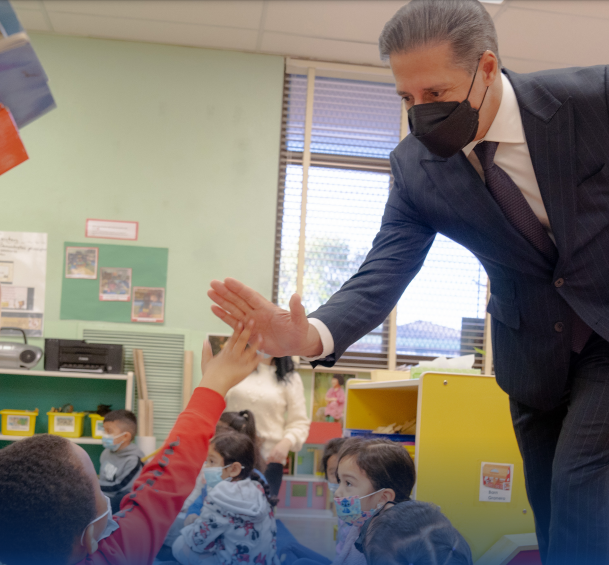

New Los Angeles Unified School District superintendent Alberto Carvalho believes the way for districts to combat for-profit entities that want to dominate the education marketplace is to launch their own programs to create excitement about publicly offered opportunities for students.

In a letter to members of the Los Angeles Unified School District community – families, students, educators and staff – newly seated superintendent Alberto Carvalho, who took the helm of the country’s second largest school district Feb. 15, pledged to accelerate opportunities for students to excel, thrive, and reach their full academic potential.

An integral part of Carvalho’s 100-day plan to achieve that goal is to “explode choice” for LAUSD students and families, a promise he is qualified to fulfill based on his performance as superintendent for Miami-Dade County Public Schools.

During his nearly 14-year tenure there, Carvalho raised Miami-Dade’s profile nationally, in part by pushing traditional district schools to compete with private and charter schools. Over the course of a decade, the percentage of Miami-Dade students enrolled in magnet schools, career academies and other district options climbed from 35 to 61%.

Today, about 75% of students in Miami-Dade have chosen the school they want to attend.

“There are some high-quality educational opportunity deserts in Los Angeles, meaning there are no exciting, motivating, relevant, and rigorous offerings in certain areas of our community," Carvalho recently told the Los Angeles Times. "So of course, if a charter school comes in, parents are going to be drawn to them. Well, why not reinvent this school system through high-demand, high-quality educational options that parents want and students need? We have some schools with thousands of students on a waitlist, why not replicate and amplify those experiences in Los Angeles?”

He added:

“I'm talking about additional magnet programs, additional expansion of single-gender schools, additional career academies, additional thematic instruction provided by the school system.”

Carvalho explained why providing greater choice is necessary:

“We are living in a highly competitive educational environment where in some instances, for-profit entities want to dominate the marketplace of education. The way to combat that is to … launch your own programs to create excitement about publicly offered opportunities for students.”

You can read more about Carvalho’s new challenge here. You can read his 100-day plan here.

Kentucky Republican Rep. Chad McCoy’s measure would add accredited public and private universities to the list of those able to authorize charter schools as well as state-approved nonprofit organizations.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Wednesday on Kentucky’s wfpl.org. You can listen to a podcast with Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill and Kentucky Rep. Chad McCoy here.

Opponents say charter schools skim off students and funding from cash-strapped public schools, and that the lack of regulation makes them less accountable to the public.

House Bill 9, sponsored by Bardstown Republican Rep. Chad McCoy, would require school districts to fund charter schools within their boundaries on a per-student basis. State, local and federal funds that would normally follow a student to a traditional public school, would instead be sent to the charter school the student attends.

The bill also expands the kinds of charter “authorizers:” regulatory bodies with the power to approve applications from groups who want to open charter schools. Authorizers also have the power to close charter schools or decline to renew contracts, which are usually time limited.

The 2017 charter school law allows school districts and mayors to authorize charter schools. McCoy’s measure adds Kentucky’s accredited public and private universities to the list, the Kentucky Board of Education, state-approved non-profit organizations and a new body the bill would create called the Kentucky Public Charter School Commission.

To continue reading, click here.

At Liberty Academy High School, learning is project and competency based with no traditional grades and no traditional seven-period day. Students are encouraged to work in small groups and interact frequently with teachers.

Editor’s note: You can watch videos of how Liberty Academy High School is rethinking education here and here.

A virtual tour of Liberty Academy High School in Liberty, Missouri, a suburb with a population of 30,167, is as notable for what you don’t see as much as for what is visible.

Instead of traditional classrooms crammed with desks, you’ll see multipurpose spaces with comfy chairs. The walls and ceilings are decorated with student artwork. Teachers collaborate with groups of students on projects and chat about goals for the day.

Rather than responding to a bell schedule, students move freely from area to area and are encouraged to come and go from campus as they practice the skills they’re learning in real life settings, thanks to agreements with more than 100 community business partners.

Social studies teacher Art Smith, right, believes strongly in each student's ability to pursue projects that interest them as a way to keep them focused on school.

Social studies teacher Art Smith, a 24-year veteran of Liberty Public Schools and a self-described “crazy guy,” redesigned the 26-year-old alternative high school’s format in 2016 with his colleagues so it would be more in line with what he calls “schools of the future.”

“We’re probably in a period of history where technology is allowing us to rethink schools,” said Smith, who doesn’t shy away from the title “education disruptor.”

During his career, Smith has tried almost every possible way to help kids derive meaning from what they’re learning, from carving canoes to building Conestoga wagons to staging archeological digs. He is among a rapidly expanding breed of educators who believe a break with the established educational model is necessary to improve the existing one.

Though Liberty Academy is a traditional district school, it looks and feels more like a public charter or private school with a model that draws inspiration from the unschooling movement of the 1960s, which encouraged exploration of activities initiated by students themselves. The basic idea is that the more personal learning is, the more meaningful it will be.

Here’s how it works. When students enter the program, they are allowed four weeks to determine their interests and long-term goals. Learning is then organized in six-week bursts of interest-based learning, which often includes participation with one of the school’s community partners in what school officials describe as “a reverse internship.”

Among the partners: a miniature horse farm, a greenhouse operation, cosmetology schools, a homeless shelter, and a host of nonprofit organizations. The aim is to allow students to explore careers, help others, and solve problems.

Students set goals based on three or four success skills during each segment. Teachers, who are referred to as advisers, help students document their growth each week and link their projects to standard and class credits.

At the end of each project, students give a presentation to a panel of at least three adults. At the end of each semester, they write an essay and display artifacts for a school and community showcase.

Learning is project based and competency based; there are no traditional grades and no traditional seven-period day. For staff members, it all adds up to an environment that looks more like life than school.

“Until you come and visit, it’s really hard to describe,” said Summer Kelly, Liberty Schools’ 2020-21 Teacher of the Year. (You can learn more about her here.) “I’m obviously a teacher, but I do way more than just teaching.”

A former middle school math teacher, Kelly left her traditional teaching job in the district three years ago to join the faculty at the alternative high school, which serves about 100 at-risk students.

Among the project-based activities available to students at Liberty Academy High is guitar building, which teaches math and engineering skills.

A typical day starts with physical activity, with a yoga class offered weekly. Afterward, students gather for a “circle meeting” and check in with their advisers and learn about trips available that day. Students then go out in small groups to participate with advisers.

“Nothing about our building is traditional in any way, and I think that’s where I needed the change,” Kelly said. “It gave me new motivation.”

Smith, the social studies teacher who helped redesign the school, said he came to a conclusion early in his career that school needed to look different to be effective, especially for students who don’t like going to school.

“They’re forced to be there, and they’re compliant and sitting in their classroom and sitting in their desks, but a lot of kids weren’t interested in anything happening on a day-to-day perspective, and that bothered me,” he said. “If they don’t love it and don’t feel intrinsically driven to be a part of it, then we should try to build a framework that does that, because no human wants to be a part of something that they don’t have ownership of and empowerment in.”

The school, which has the support of the district and school board, has won several awards and was named a grand prize winner in the 2020 Magna Awards sponsored by the National Association of School Boards. Other nearby districts have taken notice and are seeking to incorporate parts of Liberty Academy's model.

Said Smith: “We all feel blessed to be in this position at this time and to continue pushing the envelope of what school can be for kids.”

Students at Betsy Ross Arts Interdistrict Magnet School in New Haven, Connecticut, study dance, theater and visual arts with professional artists as well as certified teachers.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Danielle Gregory-Williams, a magnet recruitment specialist in New Haven, Connecticut, makes the point that education choice is alive and well in public schools, too, rounding out our coverage of National School Choice Week. It appeared this week on the New Haven Register.

National conversations about school choice often fixate on private schools or vouchers, but, in New Haven, public school choice is a critical component of efforts to expand opportunity for every child. Having choices makes public education more diverse — and that’s a great thing.

National conversations about school choice often fixate on private schools or vouchers, but, in New Haven, public school choice is a critical component of efforts to expand opportunity for every child. Having choices makes public education more diverse — and that’s a great thing.

As an umbrella term, school choice means giving families the opportunity to select from an array of learning options, so they can choose the one that best fits their child’s academic needs. Just as no two children are the same, no two public schools are the same either.

In New Haven, school choices include an incredible diversity of public options, including citywide and interdistrict magnet schools with intentional specializations, neighborhood schools rooted in local communities, and public charter schools.

Diverse school offerings honor students’ differences, ensuring that curricular programs meet kids’ specific needs and create multiple pathways to academic and career success. In particular, citywide and interdistrict magnet schools serve to reduce racial and economic isolation, bringing together students from many New Haven neighborhoods.

Just consider a few examples of what New Haven offers: At Barack H. Obama Magnet University, students focus on a STEM-curriculum and effective communication, receiving language instruction in Chinese and American Sign Language. At Betsy Ross Arts Interdistrict Magnet School, students study dance, theater and visual arts with professional artists as well as certified teachers.

To continue reading, click here.

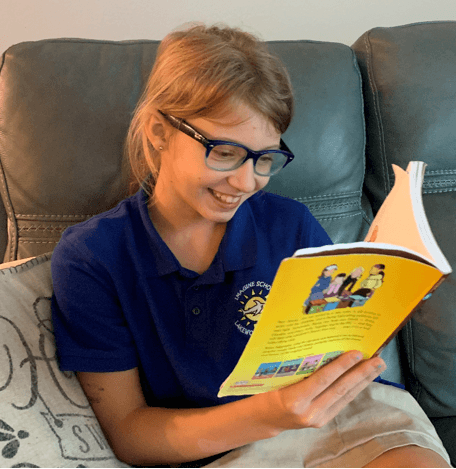

Samantha Pawlishen, a fourth-grader at Imagine School Lakewood Ranch in Manatee County, Florida, has improved her reading scores and expanded her love of reading with a Florida Reading Scholarship.

Editor's note: This feature appeared recently on Step Up For Students' marketing blog.

Lindsey Pawlishen was so confident she would pass her love of reading to her daughter that she asked for and received children’s books instead of traditional gifts at the baby shower. She began reading to Samantha when Samantha was an infant expecting to instill that love of reading.

But Samantha didn’t love reading.

“I didn’t understand it,” Lindsey said, “because everybody said if you read to your kids as soon as they are born, they’re going to be readers, but that didn’t work.”

It would turn out that Samantha’s lack of interest had something to do with the fact she struggled to read. She scored low on the English Language Arts section of the Florida Standards Assessments as a third grader during the 2020-21 school year.

That made her eligible for Florida’s Reading Scholarship, managed by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.

The scholarship was created to help public school students in third through fifth grade who struggle with reading. Those who scored a 1 or 2 on the third- or fourth-grade English Language Arts section of the Florida Standards Assessments in the prior year are eligible.

To continue reading, click here.

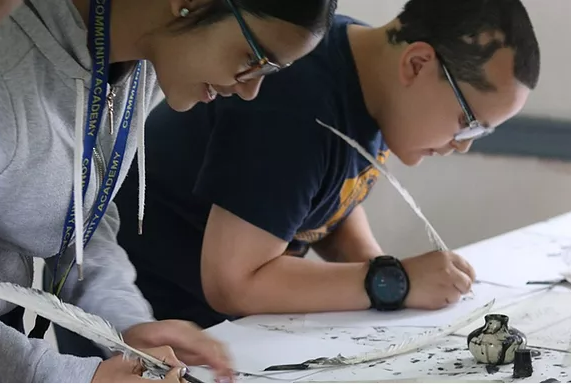

Community Academy of Philadelphia, a charter school launched in 1980, describes itself as a multi-racial, multi-ethnic, and multi-religious family that holds camaraderie and cooperation as essential values.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Lexi Boccuzzi, a University of Pennsylvania sophomore from Stamford, Conn., studying philosophy, politics and economics, appeared Monday on The Daily Pennsylvanian.

The term “school choice” is defined as “a program or policy in which students are given the choice to attend a school other than their district's public school.”

Typically, this results in school districts broadening the types of schools they have, which manifests itself in an expansion of the types of schools available to most students, which often include magnet, charter, or private schools.

While I would imagine this to be a fairly uncontroversial definition, Republicans and Democrats have remained divided on this issue for decades.

In light of increasing conversations surrounding parental involvement in education, school choice issues have grown in national prominence over the past election cycle. As a tutor with the West Philadelphia Tutoring Project, I’ve been able to get a glimpse into the lived experience of Philadelphia public school students. Combined with work on Board of Education races in my own city, it’s caused me to reflect on my own 13 years as a public school student.

These realities, juxtaposed with that of many of my Penn peers who attended private schools, led me to an interesting question: Why should the quality of education your child receives be based on your income?

The School District of Philadelphia poses a unique example on the implementation of school choice policies. In a city with one of the largest school districts in the country, the Philadelphia Board of Education is appointed, rather than elected, creating accusations of little transparency. This poses accountability red flags, making it difficult for parents to express their concerns at the ballot box.

The district also has seen increasing disparity in achievement among racial and socioeconomic groups, with only 32% of children in the third grade meeting the appropriate reading levels.

Philadelphia, unlike many other urban centers throughout the country, also has an expansive charter school system. In Philadelphia, charter schools receive district and state funding while also operating outside various city and state restrictions.

A 2015 report from the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University that looked at urban charter schools found that, in Philadelphia, socioeconomically disadvantaged students at charter schools learned more than their comparable peers at district schools in the city.

To read more, click here.

Southshore Charter Academy in Riverview, Florida, was one of four charter schools whose renewals were denied by the Hillsborough County School Board last summer. The district eventually reversed the decision.

Editor’s note: This commentary from three leaders in the charter school arena – Melissa Brady, executive director of the Florida Association of Charter School Authorizers; Alex Medler, executive director of the Colorado Association of Charter School Authorizers; and Tom Hutton, executive director of California Charter Authorizing Professionals; appeared Monday on The 74.

There is a persistent myth in education reform circles that school districts hate charter schools and cannot be trusted as charter authorizers if the sector is to succeed.

This myth obscures important realities — and opportunities — for the charter movement. These are challenging times for all public schools, and forward-thinking districts want to ensure that local charter schools have the support they need to succeed for students.

First reality check: School districts are central to charter authorizing.

About half of charter schools are authorized by districts, and nearly 90% of authorizers are districts. In many states, they are the primary or only authorizers. As leaders of state-based associations of district authorizers in Colorado (which has among the largest share of public-school students in charters), California and Florida (which have some of the nation’s largest charter sectors), we work with district leaders who recognize charters as vital parts of their local school systems.

These leaders do not consider themselves pro- or anti-charter; they simply want to perform their jobs as authorizers well, and they consider charter school students their district’s kids. When given the chance to improve authorizing, these districts embrace best practices like the National Association of Charter School Authorizers‘ Principles and Standards of Quality Charter School Authorizing, and our associations align our state-level supports for authorizers with NACSA’s approach.

Second reality check: The importance of school districts to the charter sector is only likely to increase.

In some states, major policy changes foreshadow further shifts to district authorizing. In 2016, Louisiana returned charter schools overseen by the state authorizer to the Orleans Parish. In 2019, Illinois decommissioned its state authorizer, transferring 11 state-approved charters to the State Board of Education.

While the Illinois State Board still hears appeals, districts will oversee future Illinois charter schools. That same year, California increased district discretion by narrowing criteria the State Board of Education uses to judge charter appeals and by transferring board-authorized charters to districts and county offices of education. In addition, a district may now reject a charter application based on its impact on finances and other community considerations.

To continue reading, click here.

BASIS Flagstaff Charter School, which opened in 2011, consistently makes the list of Arizona’s top charter schools.

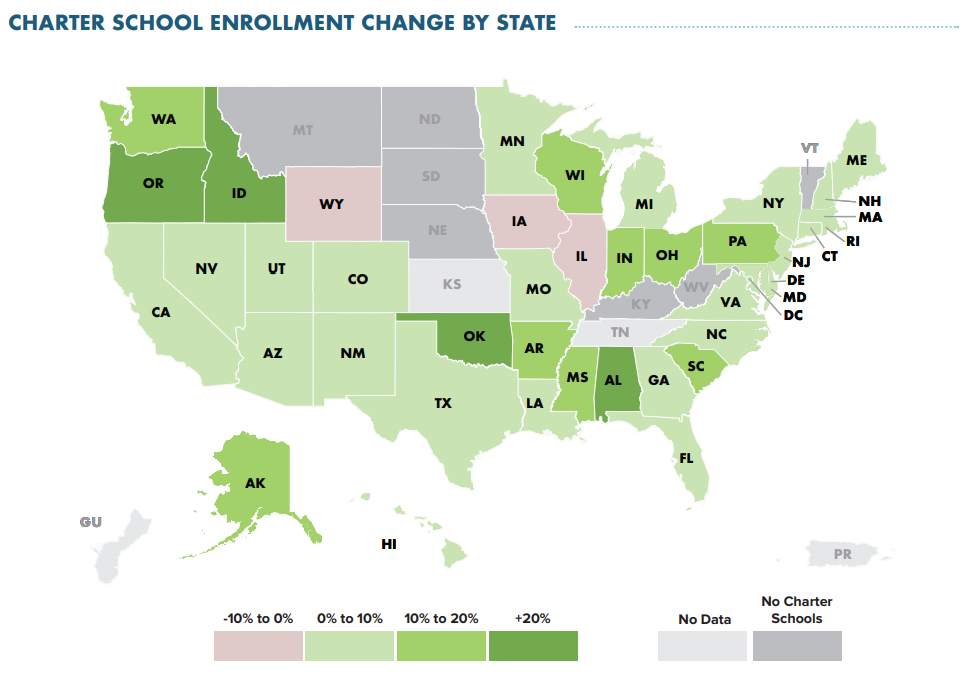

Preliminary data from a new state-level analysis from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools indicates that public charter schools posted more enrollment growth in 2020-21 than they’ve seen in the past six years, even as traditional public school enrollment declined during the first full academic year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Across 42 states included in the analysis, charter schools gained nearly 240,000 students – a 7% increase – from 2019-20 to 2020-21. Other public schools, including district-run schools, lost more than 1.4 million students, a 3% loss, during the same period.

Increases for charter schools ranged from 49 additional students in Virginia to 35,751 additional students in Oklahoma according to the report. In terms of percentages, the increase in charter enrollment ranged from 0.19% in Louisiana to nearly 78% in Oklahoma. Only three states – Illinois, Iowa and Wyoming – saw declines in charter school population.

Virtual charter school enrollments figured into the increases, the study found, particularly in Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and Utah.

In Florida, charter school enrollment increased 3.86% over the last year, a little more than 3 percentage points less than the national average, while the state’s district public schools experienced a 3.16% enrollment decrease, close to the national average.

The National Alliance consulted state educational agency websites to gather enrollment data for the study. Researchers also spoke with parents, teachers, students and school leaders to gather anecdotal data.

The report notes that a similar increase in charter school enrollment hasn’t been seen since the 2014-15 school year, when the number of charter schools grew by 4.6%, creating a 7.5% enrollment boost.

While the report doesn’t offer details on whether overall growth was due to students leaving district schools or new schools opening, the authors conclude that many families, dissatisfied with the quality of what was available to their children during the pandemic, turned to other educational options, including the “nimbleness and flexibility” of charter schools that made them “the right public school choice.”